Welcome to a myth “in outline,” one way this course will present book-length myths in ways that preserve the story and reduce the word count. We’ll use bullet points to cover the major parts of the plot following a context section that provides points of interest and background information helpful to follow the story.

Context

- The Iliad and the Trojan War epic cycle is the quintessential Greek myth; moreover, because of the influence Greco-Roman culture has had on Europe and the world, it becomes the quintessential myth of all of world mythology. So it’s worth reading first!

- The Iliad is a 10,000+ line poem written by Homer, who may or may not have been either (a) a real person as a blind wandering poet, or (b) a collection of authors who worked together under one name. (Several theories have been floated over the years.) Homer wrote The Iliad as well as The Odyssey; these two poems are listed first in any great anthology of western literature.

- Although Homer wrote down The Iliad in the 800s BC, the events themselves happened long before Homer, in about 1180 BC. Before Homer, the legend was transmitted orally for four hundred years. Elements of 1180s BC Greece (such as the Greeks being called “Achaean” rather than Greek) sit side by side with elements contemporary to Homer (such as the Achaeans wearing 800s BC armor).

- The historicity of the Trojan War frequently comes up in discussion of The Iliad. While elements of the story are doubtless embellished, it appears there really was some kind of conflict between the Achaeans of Bronze Age Greece and the inhabitants of Ilos, an outpost of the horse-loving Hittite Empire. The discovery of the ruins of Troy by German archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann in the 1800s remains one of the great surprises in the history of archaeology.

- Finally, The Iliad only covers about ten days of the entire Trojan War cycle. Homer’s other works on the subject, if they ever existed, did not survive. Lots of authors wrote about the Trojan War legends during ancient times, and the entire myth, or cycle, can be put together using all of these sources. You’ll find a summary of the complete cycle below.

Divine Origins of the War

- Peleus, a human, is married to Thetis, a minor goddess. All of the gods are invited to the wedding except Eris, the goddess of discord.

- Eris takes her revenge by hurling a golden apple into the wedding party, and it lands at the feet of three goddesses, Aphrodite (goddess of love), Hera (queen of the gods), and Athena (warrior goddess of wisdom). The apple is inscribed, “To the Fairest.”

- Each of the goddesses claim the apple is intended for her, and in the course of their argument ask Zeus, king of the gods, to settle the dispute. Zeus (perhaps wisely) declines, and the three women find young Paris, a prince of Troy shepherding on a mountainside, to decide for them who is the fairest goddess (and therefore who gets the apple).

- Each of the three goddesses seek to bribe Paris. Athena offers Paris wisdom and victory in war, Hera promises riches and power, and Aphrodite offers Paris the most beautiful woman in the world for his wife.

- Paris chooses Aphrodite—this is the so-called “Judgment of Paris.” Aphrodite tells him the most beautiful woman in the world is Helen, who turns out to be already married to Menelaus, king of Sparta in Greece.

Human Origins of the War

- Helen was the most beautiful woman in the world. When her father, Tyndareus, had begun to arrange her marriage, all the kings of Greece courted her to the point that war might erupt over who would have her as wife.

- Odysseus, king of Ithaca and known for his cleverness, devises a solution: all the princes will swear an oath to not only honor the choice Tyndareus and Helen make, but will also come to the aid of anyone who would abduct Helen from the husband chosen.

- Helen is married to Menelaus, King of Sparta and brother to Agamemnon. Agamemnon is the king of Mycenae and de facto leader of the Greek kings.

- Paris, meanwhile, leads a peace delegation to Sparta, where he is entertained royally for nine days. When Menelaus leaves the city to attend a funeral, Paris and Helen elope and escape together back to Troy. (Different versions describe Helen as willing or unwilling to go, depending on who you read.)

The Cast Assembles

- Some reluctant and others vehement, the kings of Greece keep their oath to Tyndareus and unite under Agamemnon to travel to Troy.

- The major Greek characters are as follows:

- Agamemnon –King of Mycenae, leader of the Greeks

- Menelaus –King of Sparta, brother of Agamemnon

- Nestor –King of Pylos, old and wise

- Odysseus –King of Ithaca, reluctant to go and known for his cunning

- Achilles –King of the Myrmidons, the crack fighting force of the Greeks. Achilles himself was known for being an extremely angry individual; The Iliad’s first words are literally “the wrath of Achilles.” He doesn’t get along well with Agamemnon, and is rumored to be nearly immortal—he is the son of Peleus and Thetis from the wedding mentioned above. As an infant, Achilles was dipped in the River Styx (sometimes dipped into fire) by his mother in order to make him impenetrable; all but his heel was made impervious to attack. Achilles wrestled with whether or not to go to Troy because of a prophecy concerning his life: if he did not go to war, he would live a long life, marry and have children and be happy, but no one would remember him. However, if he went to war he was guaranteed to die—but his name would live on forever in glory.

- Patroclus–The “intimate friend” of Achilles as described by the texts. Today, this is most often interpreted to mean he and Achilles were lovers.

- Ajax –King of Telamon, known for being a beast of a strong man

- The Greek fleet amassed something close to 1,000 ships and set sail for Troy. Helen’s beauty is later described as “the face that launched a thousand ships.”

- En route to Troy, in keeping with a prophecy that told the Greeks how to guarantee victory, Agamemnon sacrifices his daughter Iphigenia. This will cause him trouble back at home in the collection of stories known as the Oresteia.

- When the Greeks arrive at Troy, they find this cast assembled against them on the Trojan side:

- Priam –King of Troy, and old and mighty and well-respected leader.

- Hector –Prince of Troy, and Troy’s greatest warrior. He is widely considered one of the most honorable characters in the entire myth.

- Paris –Prince of Troy, and known for being a cowardly archer.

- Laocoon –Priest of Apollo

- Aeneas –Nephew to Priam, and one of Troy’s greatest warriors after Hector

- The Trojans also had allies from the Amazons (a female warrior tribe located in modern-day Chechnya) and from Ethiopia.

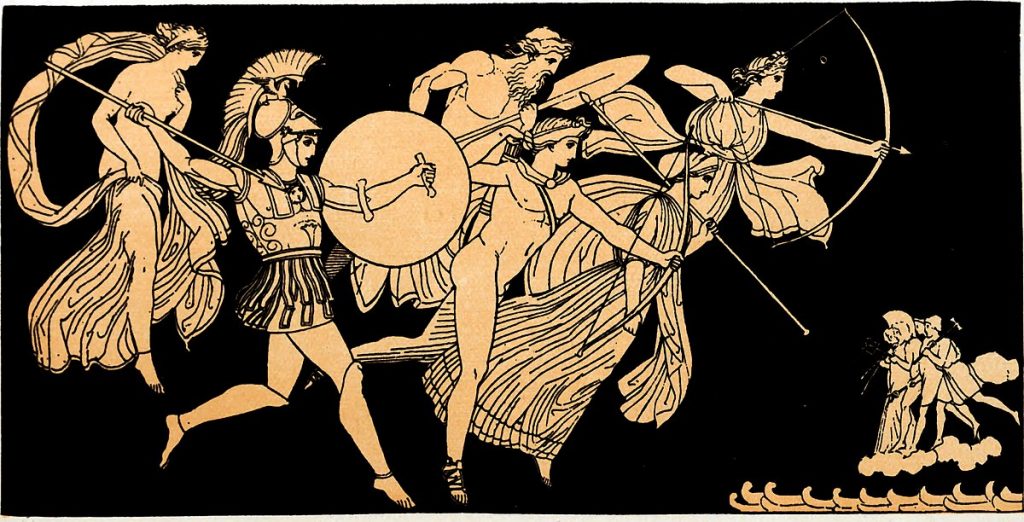

- On top of that, the gods tend to take sides in this war and fight in the actual battles by impersonating some of the heroes mentioned above.

- On the side of the Greeks are Poseidon (god of the sea and of horses), Hera, and Athena.

- On the side of the Trojans is Apollo, Ares (god of war), and Aphrodite.

The First Nine Years

- Much of the Trojan War consisted of a drawn-out siege, so summarizing the first nine years is relatively quick. The war lasted a decade (some accounts say twenty years), which is more of a symbolic number than anything else.

- The Greeks almost do not make it onto the beaches when they arrive, but Achilles single-handedly with the Myrmidons wins a great victory by securing a beachhead. In the process he takes possession of the Temple of Apollo and captures the virgin girls who care for it (this is why Apollo is against the Greeks, because they desecrated his temple).

- Agamemnon as leader of the Greeks gets the credit for this victory and thus all the spoils of war that comes with it. When Agamemnon takes away the virgin Briseis from Achilles to spite him and show Achilles who’s the boss, Achilles responds by going on strike with the Myrmidons and boycotting the war. The Greeks begin losing. Achilles returns to the war after Agamemnon, humiliated, returns Briseis to Achilles.

- Achilles will again and again spar with Agamemnon, and typically will decide to boycott the war to beat Agamemnon politically. Whenever he does so, the Greeks suffer. Usually it is Nestor and Odysseus who patch things up between the two men.

- Patroclus, who cannot stand seeing his Greek brethren being slaughtered, urges Achilles to change his mind. Achilles refuses. Patroclus decides to impersonate Achilles by donning his lover’s armor and leading the Greeks into battle (because armor was personalized back then, the soldiers would think Achilles returned and rally).

- Hector, seeing “Achilles,” challenges Patroclus to a duel and kills him. Only afterward does he realize that he killed the wrong man.

- Achilles, more furious than ever, summons Hector for a duel. This becomes one of the most famous duels of all mythology. Achilles kills Hector, and in his implacable rage lashes Hector’s body to his chariot by his feet. He proceeds to drag Hector’s body with his chariot for several laps around Troy, the royal family and citizens watching. After disgracing his foe in this way, Achilles then swears never to bury Hector—meaning Hector’s spirit cannot enter the underworld and will wander for eternity as a ghost.

- Priam, horrified, sneaks into the Greek camp under the cover of dark, pleading with Achilles for his son’s body in order to bury Hector appropriately. In a rare instance of magnanimity, Achilles gives him the body and Hector’s spirit is saved from its fate.

- In another battle, before the end of the war, Achilles does reach his doom—this time at the hands of Paris, who shoots an arrow into Achilles’s heel, the only spot where Achilles is vulnerable. This is the origin of the Achilles’ tendon.

The Trojan Horse

- In the tenth year of the war, with Achilles dead and the Greeks repeatedly driven back to the coast, morale is at an all-time low.

- It is Odysseus who dreams of using some of the Greek ships’ hulls to construct a hollow wooden horse, stuffed with Greek soldiers and left on the beaches of Troy as a supposed victory offering to the Trojans. Odysseus reasons that once the Trojans pull the horse into the city for their postwar celebrations, the Greeks soldiers can wait until nightfall to emerge and open the gates to the Greeks.

- The horse is constructed, the Greeks break camp and take their ships beyond the Trojans’ sight, and the Greek soldier Sinon is left wandering the beach to let himself be captured by the Trojans. Priam, Laocoon and his two sons, and other Trojan leaders still alive ride to the coast to inspect the horse.

- Just as the Trojan leaders become suspicious about the horse, Trojan soldiers bring forth Sinon, who lies that he barely escaped being sacrificed by the Greeks. He alleges the Greeks left in the night to return home in disgrace. The horse was created and left on the beach as an offering to Athena, he says, for safe voyages. Moreover, Sinon says, the horse was created larger than the gates of Troy because it was prophesied that whoever had the horse in their city was destined to conquer Europe.

- The Trojan leaders are won over by Sinon’s deceit, but Laocoon is still uncertain. He believes the horse is a ploy and has just about changed the minds of the Trojan leaders again when Poseidon sends two great sea serpents from the ocean onto the beach. They wrap themselves around Laocoon and his two sons and drag them to their watery deaths.

- Concluding that Sinon was right and Laocoon’s death was a sign from the gods that he was wrong, the Trojans bring the horse into the city; in some accounts they have to dismantle the gates to do so.

- After a day of celebration the Trojans go to sleep tired and probably inebriated. The Greeks sneak out of the horse, open the gate (in the versions where the gate wasn’t dismantled), recall the Greek fleet via smoke signal, and the city is taken.

- As Troy is devoured by flames, all the Trojan heroes meet their deaths with the exception of Aeneas, who leads a small band of escapees into a life of wandering exile. Agamemnon leads the Greek fleet home, smoke from Troy continuing to rise behind him.

Sequels

- The Iliad spawned multiple sequels, some much more famous than others.

- Aeneas’s journeys afterward are chronicles by Virgil in The Aeneid.

- Agamemnon’s disastrous homecoming is chronicled by the legends known as the Oresteia.

- Odysseus’s extended voyage is recorded in Homer’s Odyssey.

To cite this reading, use the following format:

“The Illiad in Outline.” Colorado Community College System, 2023.