4.3 The Minoans

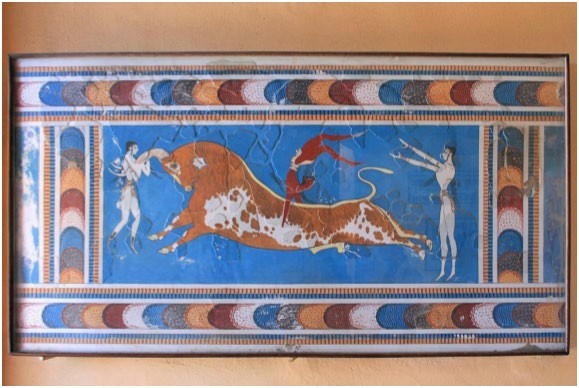

The Minoan civilization lived on the island of Crete and on small islands around it, from around 2700 BCE. until c. 1100 BCE. The Minoans had a strong trading economy supported by their strategic position in the Aegean. This position also made it difficult for other people to conquer and hold the islands, which helped to protect the people and their advanced technology and creative arts. The island appears in an important Greek myth that seems to disguise history in its depiction of a mainland Greek hero defeating the Minotaur (a giant bull). Giant bulls, now extinct, appear in much of the Minoan art. Bulls seem to have been part of a ritual and probably served as a religious symbol, important to the islanders. The Minoan influence on the fifth century Greeks did not end with the creation of epic “historic” myths. The Mycenaean culture borrowed a good deal from the Minoans and as such, the Minoans exerted influences on the later fifth century Greeks.

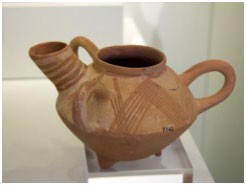

Another common use of the bull image is in the many rhytons (ritual vessels) found on Crete and the Greek Mainland that were often created in the shape of a bull’s head. In each case the rhyton has been purposefully destroyed, leading to the conclusion that it’s ritual purpose had expired. Most of these rhytons are an interesting mixture of realism and stylization. These bull vessels have even been found painted on Egyptian walls as gifts being presented to the pharaoh by a Cretan envoy. Rhytons made in the bull image are also found on mainland Greece, making it clear that the Mycenaean people who lived there were in contact with the Minoans living on the islands of the Aegean Sea, long before they themselves took over those islands.

Minoan culture produced pottery in much the same pattern as the Cycladic culture. Early potters tended to decorate in organically rendered, rather than mathematically geometric patterns. Later pottery sported more emblematic images such as stylized sea life, so important to island dwellers. Notice the comparison below.

Look at the stylized fresco above. It is fanciful and lively. There is, however, no way to know exactly what the intention behind it was. It may have been purely decorative, or it may have been intended to bring bounty from the sea. To complicate matters further, excavations and restorations of the Minoan ruins have taken place over time and have been done by several different people. Each one had different ideas about how restoration should be approached. Also, much of the area was occupied throughout so many time periods that accurate restoration is necessarily specific to an era but what is left to view is from several time periods. Early restorers often made up whatever they could not determine scientifically and in some cases artifacts were seriously modified.

The small statue known as the Minoan Snake Goddess was clearly modified by the man who found it. He put the cat on her head and added the snakes. Christopher Witcombe suggests that, “Largely on the basis of Evans’ find, the group was enthusiastically identified as the ‘Snake Goddess’ attended by three votaries. A more judicious examination of the figurines, however, suggests that the central figure, around which the three other figurines can be joined as in a circle dance, is holding not a snake but a lyre.”6

MINOAN TECHNOLOGY

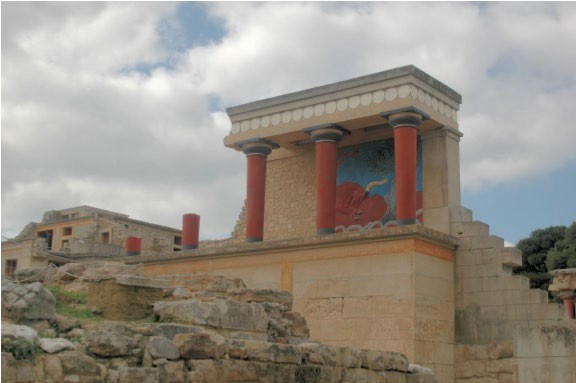

Knossos, the largest city on the island of Crete was a pretty amazing place. It boasted the oldest known flushing toilets and hypocaust-heated floors. These luxuries were not just for the now famous palace but also for the common Minoan citizen. They too had hot and cold running water as well as a drain-off system that also served as ventilation. These types of advancement are not developed in struggling cultures.

The Minoans also had a written language. Mainland Greece did not obtain one until nearly a thousand years after the fall of the Minoan culture. The Minoan language, referred to as “linear-A,” has not yet been deciphered. Linguists have found a close relationship between linear-A and Sanskrit, an ancient Indian language. This makes a great deal of sense as much of ancient Greek myth is clearly connected to stories originally written in Sanskrit and now associated with Hinduism. Within The Ramayana alone there are parallels to Helen’s kidnapping and retrieval in The Iliad and to Odysseus using a sacred bow to win back his wife in The Odyssey. Even the story of Icarus flying too close to the sun is paralleled in the Indian epic. The Minoan language can also be connected to Hittite and Armenian languages, which means that Linear-A is Indo- European in origin. DNA from a four thousand year old Minoan supports the theory that genetics and cultural ideas from Europe create the foundation for this incredible early civilization.

Above is what is known as the Palace at Knossos, on Crete. Dr Senta German states that, “The power of Evans’s interpretation and reconstruction of the site as purely Minoan – the product of the indigenous culture of that island – is very much still with us despite the fact that much has changed about how art historians and archeologists understand the different periods of construction at Knossos. Today, much of its final plan and form, which Evans reconstructed (including the Throne Room and most of the frescoes), are understood as being of Mycenaean construction (not Minoan).”9

It is, therefore, impossible to say how much influence the original inhabitants had on what is now available for viewing. It seems likely that anything that was a benefit, like running water, would continue to be used and maintained. As for the Minoan influence on the art, it was probably considerable. The images are often of life at sea. As the Mycenaeans lived on the mainland, those images would likely have been drawn from earlier art from the area.

The story of the Minotaur (half bull and half human), that disguises the historic takeover of the islands is briefly outlined here. A young man named, Theseus, was to become the next ruler of Mainland Greece, probably through his association with the main city, Mycenae. He volunteered to go to the island of king Minos as one of the sacrifices required of the Mainland Greeks. Each year a dozen young men and women were sent to the main island and sacrificed as revenge for the loss of Minos’ son, which he blamed on the Mycenaean Greeks. After proving to Minos that his real father was Poseidon, Theseus went to the maze, where it was expected that he would succumb to the Minotaur that lives there.

Ariadne, King Minos’ daughter, helps Theseus win the challenge by providing him with a string that will allow him to find his way out of the maze where the Minotaur lives. While in the maze, Theseus kills the sleeping Minotaur and escapes the maze by following the string.

Theseus ignores his promise to Ariadne that he would take her with him, after all, anyone who would betray their family does not deserve to be treated kindly. This attitude toward family is still present in fifth century Greece. Theseus returned to his homeland and took over the kingdom as his father, Agaeas, threw himself into the sea, (named The Aegean, after him) when he thought that his adopted son had died. Although this story is a myth, it refers to many historic subjects and as such, seems to be a disguised history of the Mycenaean culture overtaking the bull enthused Minoans, ending whatever strife they had caused.

In spite of the difficulties in assessing the available evidence, it is clear that there are many ideas in the Minoan culture that are shared by or borrowed from other Bronze Age cultures. It is also clear that many of those ideas reappear in later Greek art, literature and architecture. Even the Mythical story of the Mainland Greek hero Theseus defeating the Minotaur can be traced to the history of Bronze Age dwellers in and around the Aegean Sea. The Mycenaean culture did indeed take over the islands. Although they did not remain long, they seem to have brought their own ideas there as well as taking Minoan ideas and art styles back to Mainland Greece.

References:

1. Bull Leaping fresco by Lapplaender is licensed as [CC BY-SA 3.0 de (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by- sa/3.0/de/deed.en)] https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Knossos_-_06.jpg

2. Photo by Wolfgang Sauber [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)] https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:AMI_-_Stierrhyton.jpg

3. Early Minoan pottery from Pyrgos burial cave, 3000-2600 BC. Archaeological Museum of Heraklion. Zde [CC BY-SA 4.0 https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Early_Minoan_pottery_from_Pyrgos,_3000-2600_BC,_AMH,_144535.jpg

4. Photo by, Cyprus Monnu, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Arheologicheski-Octopus.jpg

5. Photo by Jebulon, CC0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Queen%27s_Megaron_with_dolphins_Knossos_Palace.jpg

6. Witcombe, Christopher, L.C.E. “Women in the Aegean: Minoan Snake Goddess.” Art History Resources. 2000. Accessed 10/09/19

7. Photo by Olaf Tausch, CC BY 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kleine_Schlangengöttin_01.jpg

8. No machine-readable author provided. Harrieta171 assumed (based on copyright claims). [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/)] https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Knossos_Palais_2.JPG

9. Dr. Senta German, “The Palace at Knossos (Crete),” in 2019, July 11, 2018, accessed October 9, 2019. Smarthistory.

10. Photo by Jebulon [CC0] https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Throne_of_Minos_at_Knossos_Palace.jpg