2.1 The First Civilizations: Mesopotamia

The first civilization emerged during the fourth millennium BCE in Mesopotamia, the “fertile crescent,” between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. Around 3500 BCE, Sumer ushered in the Bronze Age, and civilization.

The Bronze Age is an archaeological designation, indicating that now people had the technology to work with and cast in bronze, a technological leap above the Stone Age.

Sumer is the earliest civilization known to history. According to the Free Dictionary, civilization is defined as “An advanced state of intellectual, cultural, and material development in human society, marked by progress in the arts and sciences, the extensive use of record-keeping, including writing, and the appearance of complex political and social institutions.”

The Sumerians were the first to create writing, cuneiform, which allowed for record-keeping, but also allowed for the creation of the first work of literature, the Epic of Gilgamesh. The Sumerians had organized religion, with a set of gods and god-man relations, and they had well-organized city-states.

In the Ancient Near East, the Sumerians were followed by other civilizations, who adopted cuneiform script, and other aspects of Sumerian inventions, such as lost-wax casting in Bronze. Other Ancient Near Eastern cultures included the Akkadians, Babylonians and Assyrians.

As you read about Mesopotamian civilizations, think about the distinct contributions of these people to humankind – in terms of religion, writing, literature, law – and how they still influence us, today.

Ancient Near East: Cradle of civilization

The cradle of civilization

Mesopotamia, the area between the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers (in modern day Iraq), is often referred to as the cradle of civilization because it is the first place where complex urban centers grew. The history of Mesopotamia, however, is inextricably tied to the greater region, which is comprised of the modern nations of Egypt, Iran, Syria, Jordan, Israel, Lebanon, the Gulf states and Turkey. We often refer to this region as the Near or Middle East.

What’s in a name?

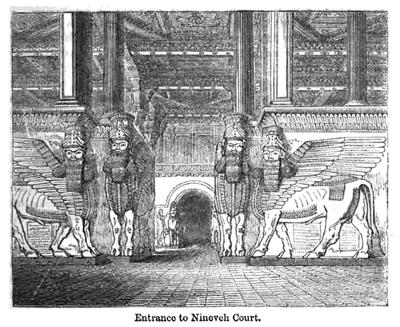

Why is this region named this way? What is it in the middle of or near to? It is the proximity of these countries to the West (to Europe) that led this area to be termed “the near east.” Ancient Near Eastern Art has long been part of the history of Western art, but history didn’t have to be written this way. It is largely because of the West’s interests in the Biblical “Holy Land” that ancient Near Eastern materials have been be regarded as part of the Western canon of the history of art. An interest in finding the locations of cities mentioned in the Bible (such as Nineveh and Babylon) inspired the original English and French 19th century archaeological expeditions to the Near East. These sites were discovered and their excavations revealed to the world a style of art which had been lost.

The excavations inspired The Nineveh Court at the 1851 World’s Fair in London and a style of decorative art and architecture called Assyrian Revival. Ancient Near Eastern art remains popular today; in 2007 a 2.25 inch high, early 3rd millennium limestone sculpture, the Guennol Lioness, was sold for 57.2 million dollars, the second most expensive piece of sculpture sold at that time.

A complex history

The history of the Ancient Near East is complex and the names of rulers and locations are often difficult to read, pronounce and spell. Moreover, this is a part of the world which today remains remote from the West culturally while political tensions have impeded mutual understanding. However, once you get a handle on the general geography of the area and its history, the art reveals itself as uniquely beautiful, intimate and fascinating in its complexity.

Geography and the growth of cities

Mesopotamia remains a region of stark geographical contrasts: vast deserts rimmed by rugged mountain ranges, punctuated by lush oases. Flowing through this topography are rivers and it was the irrigation systems that drew off the water from these rivers, specifically in southern Mesopotamia, that provided the support for the very early urban centers here.

The region lacks stone (for building), precious metals and timber. Historically, it has relied on the long-distance trade of its agricultural products to secure these materials. The large-scale irrigation systems and labor required for extensive farming was managed by a centralized authority. The early development of this authority, over large numbers of people in an urban center, is really what distinguishes Mesopotamia and gives it a special position in the history of Western culture. Here, for the first time, thanks to ample food and a strong administrative class, the West develops a very high level of craft specialization and artistic production.

Additional resources:

Mesopotamia on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Timeline of Art History

Ancient Near Eastern Art at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Dr. Senta German, “Ancient Near East: Cradle of civilization,” in Smarthistory, August 8, 2015, accessed February 6, 2017, https://smarthistory.org/ancient-near-east-cradle-of-civilization/.

As you read about Sumerian art, think about the many ways that humans use writing. How was writing important or humans in the Ancient Near East?

Sumerian art, an introduction

by DR. SENTA GERMAN

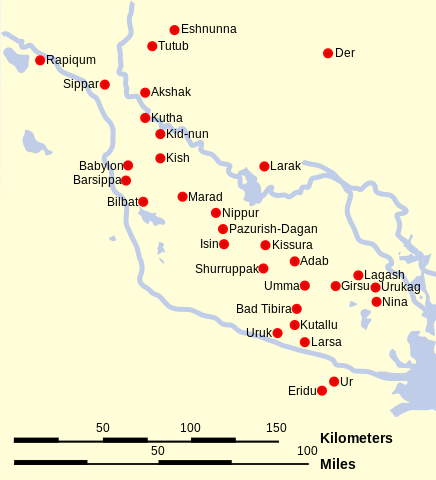

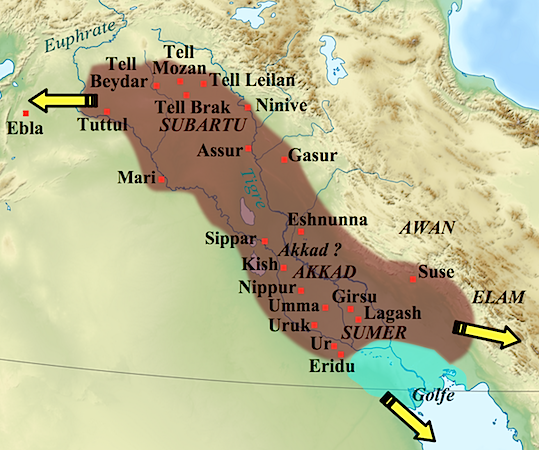

Cities of ancient Sumer, photo (CC BY 3.0)

The region of southern Mesopotamia is known as Sumer, and it is in Sumer that we find some of the oldest known cities, including Ur and Uruk.

Uruk

Prehistory ends with Uruk, where we find some of the earliest written records. This large city-state (and it environs) was largely dedicated to agriculture and eventually dominated southern Mesopotamia. Uruk perfected Mesopotamian irrigation and administration systems.

An agricultural theocracy

Within the city of Uruk, there was a large temple complex dedicated to Innana, the patron goddess of the city. The City-State’s agricultural production would be “given” to her and stored at her temple. Harvested crops would then be processed (grain ground into flour, barley fermented into beer) and given back to the citizens of Uruk in equal share at regular intervals.

Reconstruction of the ziggurat at Uruk dedicated to the goddess Inanna (created by Artefacts/DAI, copyright DAI, CC-BY-NC-ND)

The head of the temple administration, the chief priest of Innana, also served as political leader, making Uruk the first known theocracy. We know many details about this theocratic administration because the Sumerians left numerous documents in the form of tablets written in cuneiform script.

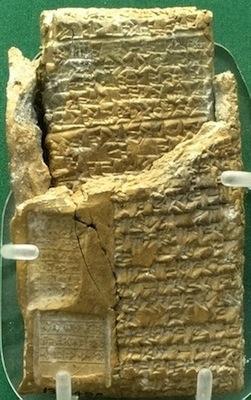

Cuneiform tablet still in its clay case: legal case from Niqmepuh, King of Iamhad (Aleppo), 1720 B.C.E., 3.94 x 2″ (British Museum)

It is almost impossible to imagine a time before writing. However, you might be disappointed to learn that writing was not invented to record stories, poetry, or prayers to a god. The first fully developed written script, cuneiform, was invented to account for something unglamorous, but very important—surplus commodities: bushels of barley, head of cattle, and jars of oil!

The origin of written language (c. 3200 B.C.E.) was born out of economic necessity and was a tool of the theocratic (priestly) ruling elite who needed to keep track of the agricultural wealth of the city-states. The last known document written in the cuneiform script dates to the first century C.E. Only the hieroglyphic script of the Ancient Egyptians lasted longer.

A reed and clay tablet

A single reed, cleanly cut from the banks of the Euphrates or Tigris river, when pressed cut-edge down into a soft clay tablet, will make a wedge shape. The arrangement of multiple wedge shapes (as few as two and as many as ten) created cuneiform characters. Characters could be written either horizontally or vertically, although a horizontal arrangement was more widely used.

Very few cuneiform signs have only one meaning; most have as many as four. Cuneiform signs could represent a whole word or an idea or a number. Most frequently though, they represented a syllable. A cuneiform syllable could be a vowel alone, a consonant plus a vowel, a vowel plus a consonant and even a consonant plus a vowel plus a consonant. There isn’t a sound that a human mouth can make that this script can’t record.

Probably because of this extraordinary flexibility, the range of languages that were written with cuneiform across history of the Ancient Near East is vast and includes Sumerian, Akkadian, Amorite, Hurrian, Urartian, Hittite, Luwian, Palaic, Hatian and Elamite.

Additional resources:

Short video from Artefacts about the reconstruction of the Ziggurat (there is no sound on this video)

Cylinder seals on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

The Origins of Writing on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Dr. Senta German, “Sumerian art, an introduction,” in Smarthistory, August 8, 2015, accessed February 6, 2017, https://smarthistory.org/sumerian-art-an-introduction/.

Epic of Gilgamesh

The Epic of Gilgamesh is an epic poem from Babylonia and arguably the oldest known work of literature. The story includes a series of legends and poems integrated into a longer Akkadian epic about the hero-king Gilgamesh of Uruk (Erech, in the Bible), a ruler of the third millennium B.C.E. Several versions have survived, the most complete being preserved on eleven clay tablets in the library of the seventh-century B.C.E. Assyrian king Ashurbanipal.

The essential story tells of the spiritual maturation of the heroic Gilgamesh, the powerful but self-centered king who tyrannizes his people and even disregards the gods. He is part divine and part human. Through his adventures, Gilgamesh first begins to know himself through experiencing the death of his only friend, Enkidu. Seeking the secret of eternal life, he travels on the archetypal hero’s journey, ultimately returning to Uruk a much wiser man than when he left and reconciled to his mortality.

Did you know?

The story of Noah’s Great Flood in the Bible directly parallels one of the stories in the Gilgamesh epic?

The epic appears to have been widely known in ancient times and to have influenced important works of literature, from the book of Genesis to The Odyssey. There is a striking parallel with the story of Noah’s flood in Genesis.

Episodes in Gilgamesh foreshadow many other later stories in both Biblical and secular literature:

The Fall of Man (the naked savage Enkidu’s harmony with nature is broken when he is seduced by the prostitute Shamhat, who initiates him to “knowledge of good and evil,” and makes him aware that he is naked and ashamed, at which point she clothes him).

David and Jonathan (Enkidu’s sacrificial loyalty for his rival, Gilgamesh).

The Fruit of the Tree of Life (the plant of eternal youth stolen by a serpent).

Hercules (Gilgamesh as the nearly immortal demi-god and great, but flawed, hero).

Even with its missing lines and far from seamless narrative style, the Epic of Gilgamesh is a work of great literature—all the more wonderful because it predates all others. It is widely read in translation, and its hero has become a minor icon of popular culture.

Epic of Gilgamesh, Flood Story

The Epic of Gilgamesh is, perhaps, the oldest written story on Earth. It comes to us from Ancient Sumeria, and was originally written on 12 clay tablets in cunieform script. It is about the adventures of the historical King of Uruk (somewhere between 2750 and 2500 BCE).

Many early civilizations have flood stories. As you read this, think about why they might. What similarities are there to the Biblical flood story of Noah and the Ark?

Ancient Texts. (n.d.). Epic of Gilgamesh, Tablet 11, Flood Story. Retrieved from http://www.ancienttexts.org/library/mesopotamian/gilgamesh/tab11.htm

The noise of mankind bothered the gods, who could not sleep….

Utanapishtim spoke to Gilgamesh, saying:

“I will reveal to you, Gilgamesh, a thing that is hidden,

a secret of the gods I will tell you!

Shuruppak, a city that you surely know,

situated on the banks of the Euphrates,

that city was very old, and there were gods inside it.

The hearts of the Great Gods moved them to inflict the Flood.

Their Father Anu uttered the oath (of secrecy),

Valiant Enlil was their Adviser,

Ninurta was their Chamberlain,

Ennugi was their Minister of Canals.

Ea, the Clever Prince(?), was under oath with them

so he repeated their talk to the reed house:

‘Reed house, reed house! Wall, wall!

O man of Shuruppak, son of Ubartutu:

Tear down the house and build a boat!

Abandon wealth and seek living beings!

Spurn possessions and keep alive living beings!

Make all living beings go up into the boat.

The Rain

Six days and seven nights

came the wind and flood, the storm flattening the land.

When the seventh day arrived, the storm was pounding,

the flood was a war–struggling with itself like a woman

writhing (in labor).

The sea calmed, fell still, the whirlwind (and) flood stopped up.

I looked around all day long–quiet had set in

and all the human beings had turned to clay!

The terrain was as flat as a roof.

I opened a vent and fresh air (daylight!) fell upon the side of

my nose.

I fell to my knees and sat weeping,

tears streaming down the side of my nose.

I looked around for coastlines in the expanse of the sea,

and at twelve leagues there emerged a region (of land).

On Mt. Nimush the boat lodged firm,

Mt. Nimush held the boat, allowing no sway.

One day and a second Mt. Nimush held the boat, allowing

no sway.

A third day, a fourth, Mt. Nimush held the boat, allowing

no sway.

A fifth day, a sixth, Mt. Nimush held the boat, allowing

no sway.

When a seventh day arrived

I sent forth a dove and released it.

The dove went off, but came back to me;

no perch was visible so it circled back to me.

I sent forth a swallow and released it.

The swallow went off, but came back to me;

no perch was visible so it circled back to me.

I sent forth a raven and released it.

The raven went off, and saw the waters slither back.

It eats, it scratches, it bobs, but does not circle back to me.

Then I sent out everything in all directions and sacrificed

(a sheep).

I offered incense in front of the mountain-ziggurat.

Seven and seven cult vessels I put in place,

and (into the fire) underneath (or: into their bowls) I poured

reeds, cedar, and myrtle.

The gods smelled the savor,

the gods smelled the sweet savor,

and collected like flies over a (sheep) sacrifice.

If you wish to read more of the Epic of Gilgamesh, here is another selection. If not, skip down to “Art of Akkad.”

Gilgamesh is led to the Ferryman

Then Gilgamesh raised a punting pole

and drew the boat to shore.

Utanapishtim spoke to Gilgamesh, saying:

“Gilgamesh, you came here exhausted and worn out.

What can I give you so you can return to your land?

I will disclose to you a thing that is hidden, Gilgamesh,

a… I will tell you.

There is a plant… like a boxthorn,

whose thorns will prick your hand like a rose.

If your hands reach that plant you will become a young

man again.”

Hearing this, Gilgamesh opened a conduit(!) (to the Apsu)

and attached heavy stones to his feet.

They dragged him down, to the Apsu they pulled him.

He took the plant, though it pricked his hand,

and cut the heavy stones from his feet,

letting the waves(?) throw him onto its shores.

Gilgamesh spoke to Urshanabi, the ferryman, saying:

“Urshanabi, this plant is a plant against decay(!)

by which a man can attain his survival(!).

I will bring it to Uruk-Haven,

and have an old man eat the plant to test it.

The plant’s name is ‘The Old Man Becomes a Young Man.'”

Then I will eat it and return to the condition of my youth.”

At twenty leagues they broke for some food,

at thirty leagues they stopped for the night.

Seeing a spring and how cool its waters were,

Gilgamesh went down and was bathing in the water.

A snake smelled the fragrance of the plant,

silently came up and carried off the plant.

While going back it sloughed off its casing.’

At that point Gilgamesh sat down, weeping,

his tears streaming over the side of his nose.

“Counsel me, O ferryman Urshanabi!

For whom have my arms labored, Urshanabi!

For whom has my heart’s blood roiled!

I have not secured any good deed for myself,

but done a good deed for the ‘lion of the ground’!”

Now the high waters are coursing twenty leagues distant,’

as I was opening the conduit(?) I turned my equipment over

into it (!).

What can I find (to serve) as a marker(?) for me!

I will turn back (from the journey by sea) and leave the boat by

the shore!”.

The Bronze Age is so-called due to the new metal-working technology that emerged, in the Ancient Near East, during the fourth millennium B.C.E. Look at the bronze sculpture, Head of an Akkadian Ruler. What role does art play in being human? In civilization?

Art of Akkad, an introduction

Akkad

Competition between Akkad in the north and Ur in the south created two centralized regional powers at the end of the third millennium (c. 2334–2193 B.C.E.).

Map showing the approximate extension of the Akkad empire during the reign of Narâm-Sîn, yellow arrows indicate the directions in which military campaigns were conducted, photo (CC BY-SA 3.0)

This centralization was military in nature and the art of this period generally became more martial. The Akkadian Empire was begun by Sargon, a man from a lowly family who rose to power and founded the royal city of Akkad (Akkad has not yet been located, though one theory puts it under modern Baghdad).

Head of an Akkadian Ruler

Head of Akkadian Ruler, 2250-2200 B.C.E. (Iraqi Museum, Baghdad – looted?)

This image of an unidentified Akkadian ruler (some say it is Sargon, but no one knows) is one of the most beautiful and terrifying images in all of Ancient Near Eastern art. The life-sized bronze head shows in sharp geometric clarity, locks of hair, curled lips and a wrinkled brow. Perhaps more awesome than the powerful and somber face of this ruler is the violent attack that mutilated it in antiquity.

Ur

The kingdom of Akkad ends with internal strife and invasion by the Gutians from the Zagros mountains to the northeast. The Gutians were ousted in turn and the city of Ur, south of Uruk, became dominant. King Ur-Nammu established the third dynasty of Ur, also referred to as the Ur III period.

Dr. Senta German, “Art of Akkad, an introduction,” in Smarthistory, August 8, 2015, accessed February 6, 2017, https://smarthistory.org/art-of-akkad-an-introduction/.

As you look at and read about ziggurats, how were they used by Bronze-Age people? How are the similar to – and different from – Egyptian pyramids?

Ziggurat of Ur

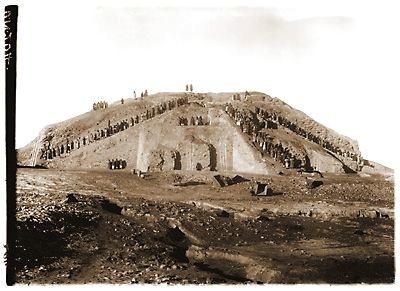

Ziggurat of Ur, c. 2100 B.C.E. mud brick and baked brick, Tell el-Mukayyar, Iraq (largely reconstructed)

The Great Ziggurat

The ziggurat is the most distinctive architectural invention of the Ancient Near East. Like an ancient Egyptian pyramid, an ancient Near Eastern ziggurat has four sides and rises up to the realm of the gods. However, unlike Egyptian pyramids, the exterior of Ziggurats were not smooth but tiered to accommodate the work which took place at the structure as well as the administrative oversight and religious rituals essential to Ancient Near Eastern cities. Ziggurats are found scattered around what is today Iraq and Iran, and stand as an imposing testament to the power and skill of the ancient culture that produced them.

One of the largest and best-preserved ziggurats of Mesopotamia is the great Ziggurat at Ur. Small excavations occurred at the site around the turn of the twentieth century, and in the 1920s Sir Leonard Woolley, in a joint project with the University of Pennsylvania Museum in Philadelphia and the British Museum in London, revealed the monument in its entirety.

Woolley Photo of the Ziggurat of Ur with workers Ziggurat of Ur, c. 2100 B.C.E., Woolley excavation workers (Tell el-Mukayyar, Iraq)

What Woolley found was a massive rectangular pyramidal structure, oriented to true North, 210 by 150 feet, constructed with three levels of terraces, standing originally between 70 and 100 feet high. Three monumental staircases led up to a gate at the first terrace level. Next, a single staircase rose to a second terrace which supported a platform on which a temple and the final and highest terrace stood. The core of the ziggurat is made of mud brick covered with baked bricks laid with bitumen, a naturally occurring tar. Each of the baked bricks measured about 11.5 x 11.5 x 2.75 inches and weighed as much as 33 pounds. The lower portion of the ziggurat, which supported the first terrace, would have used some 720,000 baked bricks. The resources needed to build the Ziggurat at Ur are staggering.

Moon goddess Nanna

The Ziggurat at Ur and the temple on its top were built around 2100 B.C.E. by the king Ur-Nammu of the Third Dynasty of Ur for the moon goddess Nanna, the divine patron of the city state. The structure would have been the highest point in the city by far and, like the spire of a medieval cathedral, would have been visible for miles around, a focal point for travelers and the pious alike. As the Ziggurat supported the temple of the patron god of the city of Ur, it is likely that it was the place where the citizens of Ur would bring agricultural surplus and where they would go to receive their regular food allotments. In antiquity, to visit the ziggurat at Ur was to seek both spiritual and physical nourishment.

Ziggurat at Ali Air Base Iraq, 2005 Ziggurat of Ur, partly restored, c. 2100 B.C.E. mudbrick and baked brick Tell el-Mukayyar, Iraq

Clearly the most important part of the ziggurat at Ur was the Nanna temple at its top, but this, unfortunately, has not survived. Some blue glazed bricks have been found which archaeologists suspect might have been part of the temple decoration. The lower parts of the ziggurat, which do survive, include amazing details of engineering and design. For instance, because the unbaked mud brick core of the temple would, according to the season, be alternatively more or less damp, the architects included holes through the baked exterior layer of the temple allowing water to evaporate from its core. Additionally, drains were built into the ziggurat’s terraces to carry away the winter rains.

Hussein’s assumption

US soldiers decend the Ziggurat of Ur, Tell el-Mukayyar, Iraq

The Ziggurat at Ur has been restored twice. The first restoration was in antiquity. The last Neo-Babylonian king, Nabodinus, apparently replaced the two upper terraces of the structure in the 6th century B.C.E. Some 2400 years later in the 1980s, Saddam Hussein restored the façade of the massive lower foundation of the ziggurat, including the three monumental staircases leading up to the gate at the first terrace. Since this most recent restoration, however, the Ziggurat at Ur has experienced some damage. During the recent war led by American and coalition forces, Saddam Hussein parked his MiG fighter jets next to the Ziggurat, believing that the bombers would spare them for fear of destroying the ancient site. Hussein’s assumptions proved only partially true as the ziggurat sustained some damage from American and coalition bombardment.

Dr. Senta German, “Ziggurat of Ur,” in Smarthistory, August 8, 2015, accessed February 6, 2017, https://smarthistory.org/ziggurat-of-ur/.

Have you heard of Nebuchadnezzar? The Tower of Babel? The Hanging Gardens of Babylon? They have haunted human imagination since Babylonian times.

Babylonia, an introduction

On the River Euphrates

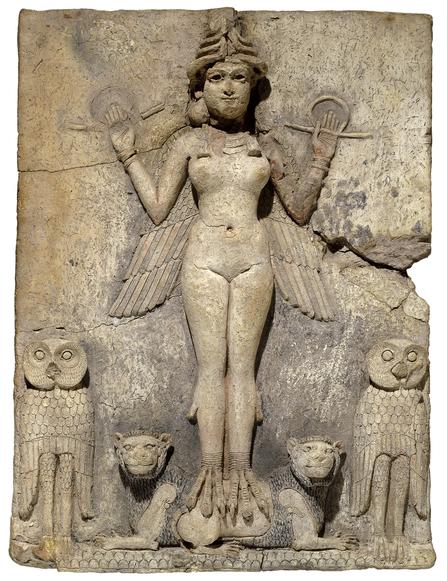

The city of Babylon on the River Euphrates in southern Iraq is mentioned in documents of the late third millennium B.C.E. and first came to prominence as the royal city of King Hammurabi (about 1790-1750 B.C.E.). He established control over many other kingdoms stretching from the Persian Gulf to Syria. The British Museum holds one of the iconic artworks of this period, the so-called “Queen of the Night.”

The “Queen of the Night” Relief, 1800-1750 B.C.E., Old Babylonian, baked straw-tempered clay, 49 x 37 x 4.8 cm © Trustees of the British Museum

From around 1500 B.C.E. a dynasty of Kassite kings took control in Babylon and unified southern Iraq into the kingdom of Babylonia. The Babylonian cities were the centers of great scribal learning and produced writings on divination, astrology, medicine and mathematics. The Kassite kings corresponded with the Egyptian Pharaohs as revealed by cuneiform letters found at Amarna in Egypt, now in the British Museum.

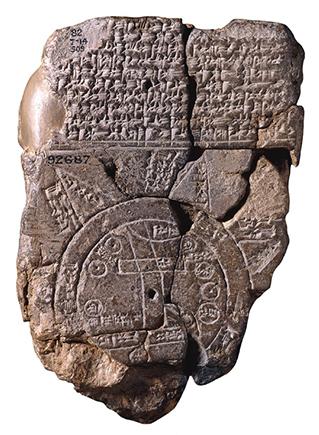

Babylonia had an uneasy relationship with its northern neighbor Assyria and opposed its military expansion. In 689 B.C.E. Babylon was sacked by the Assyrians but as the city was highly regarded it was restored to its former status soon after. Other Babylonian cities also flourished; scribes in the city of Sippar probably produced the famous “Map of the World” (see image below).

Babylonian kings

After 612 B.C.E. the Babylonian kings Nabopolassar and Nebuchadnezzar II were able to claim much of the Assyrian empire and rebuilt Babylon on a grand scale. Nebuchadnezzar II rebuilt Babylon in the sixth century B.C.E. and it became the largest ancient settlement in Mesopotamia. There were two sets of fortified walls and massive palaces and religious buildings, including the central ziggurat tower. Nebuchadnezzar is also credited with the construction of the famous “Hanging Gardens.” However, the last Babylonian king Nabonidus (555-539 B.C.E.) was defeated by Cyrus II of Persia and the country was incorporated into the vast Achaemenid Persian Empire.

New Threats

Map of the World, Babylonian, c. 700-500 B.C.E., clay, 12.2 x 8.2 cm, probably from Sippar, southern Iraq © Trustees of the British Museum

Babylon remained an important center until the third century B.C.E., when Seleucia-on-the-Tigris was founded about ninety kilometers to the north-east. Under Antiochus I (281-261 B.C.E.) the new settlement became the official Royal City and the civilian population was ordered to move there. Nonetheless a village existed on the old city site until the eleventh century AD. Babylon was excavated by Robert Koldewey between 1899 and 1917 on behalf of the Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft. Since 1958 the Iraq Directorate-General of Antiquities has carried out further investigations. Unfortunately, the earlier levels are inaccessible beneath the high water table. Since 2003, our attention has been drawn to new threats to the archaeology of Mesopotamia, modern day Iraq.

For two thousand years the myth of Babylon has haunted the European imagination. The Tower of Babel and the Hanging Gardens, Belshazzar’s Feast and the Fall of Babylon have inspired artists, writers, poets, philosophers and film makers.

© Trustees of the British Museum

The British Museum, “Babylonia, an introduction,” in Smarthistory, August 29, 2016, accessed February 6, 2017, https://smarthistory.org/babylonia-an-introduction/.

Why do humans have the need for organization in civilization? Law codes are one way to keep humans in order. Consider the difference between foundational ethical or legal concepts (the spirit of the law) and particular applications (the letter of the law), such as punishments for offences. How might Hammurabi’s law codes have influenced other cultures (including our own)? How different were Hammurabi’s law codes from our laws?

Code of Hammurabi

The Code of Hammurabi (also known as the Codex Hammurabi and Hammurabi’s Code), created ca. 1780 B.C.E., is one of the earliest sets of laws found and one of the best preserved examples of this type of document from ancient Mesopotamia. The code is a collection of the legal decisions made by Hammurabi during his reign as king of Babylon, inscribed on a stele.

The text contains a list of crimes and their various punishments, as well as settlements for common disputes and guidelines for citizens’ conduct. It focuses on theft, property damage, women’s rights, marriage rights, children’s rights, slave rights, murder, death, and injury. The Code does not specify a procedure for defense against charges, though it does imply one’s right to present evidence. The stele was openly displayed for all to see; thus, no one could plead ignorance of the law as an excuse. Scholars presume that few people could read in that era and that much of the code was handed down through oral communication.

Although a social hierarchy placed some in privileged positions, the code proscribed punishments applicable to all classes, notwithstanding that punishments varied depending on the status of offenders and victims.

As the rule of conduct was binding on all members of the community, state, and nation, the code provided coherent boundaries for citizens in a complex society. Citizens understood that abiding by these rules meant freedom to live and prosper. Although punishments for many minor infractions appear draconian by contemporary standards, the code formalized the fundamental responsibility of the individual to act in the context of the public interest. The code was grounded in commonly accepted principles of morality and ethics and provided a clear set of norms for all members of society to live together in peace.

Hammurabi: The king who made the four quarters of the earth obedient

A stele is a vertical stone monument or marker often inscribed with text or with relief carving.

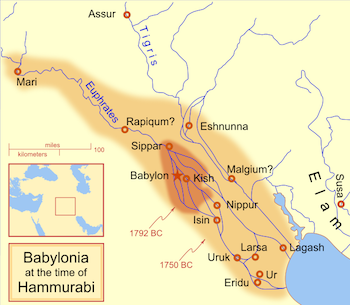

Babylonia at the time of Hammurabi

Hammurabi of the city state of Babylon conquered much of northern and western Mesopotamia and by 1776 B.C.E., he is the most far-reaching leader of Mesopotamian history, describing himself as “the king who made the four quarters of the earth obedient.” Documents show Hammurabi was a classic micro-manager, concerned with all aspects of his rule, and this is seen in his famous legal code, which survives in partial copies on this stele in the Louvre and on clay tablets (a stele is a vertical stone monument or marker often inscribed with text or with relief carving). We can also view this as a monument presenting Hammurabi as an exemplary king of justice.

What is interesting about the representation of Hammurabi on the legal code stele is that he is seen as receiving the laws from the god Shamash, who is seated, complete with thunderbolts coming from his shoulders. The emphasis here is Hammurabi’s role as pious theocrat, and that the laws themselves come from the god.

The Code of Hammurabi, Kind of Babylon

§ 8. If a man has stolen ox or sheep or ass, or pig, or ship, whether from the temple or the palace, he shall pay thirtyfold. If he be a poor man, he shall render tenfold. If the thief has nought to pay, he shall be put to death.

§ 9. If a man who has lost something of his, something of his that is lost has been seized in the hand of a man, the man in whose hand the lost thing has been seized has said, ‘A giver gave it me,’ or ‘I bought it before witnesses,’ and the owner of the thing that is lost has said, ‘Verily, I will bring witnesses that know my lost property,’ the buyer has brought the giver who gave it him and the witnesses before whom he bought, and the owner of the lost property has brought the witnesses who know his lost property, the judge shall see their depositions, the witnesses before whom the purchase was made and the witnesses knowing the lost property shall say out before God what they know; and if the giver has acted the thief he shall be put to death, the owner of the lost property shall take his lost property, the buyer shall take the money he paid from the house of the giver.

§ 10. If the buyer has not brought the giver who gave it him and the witnesses before whom he bought, and the owner of the lost property has brought the witnesses knowing his lost property, the buyer has acted the thief, he shall be put to death; the owner of the lost property shall take his lost property.

§ 11. If the owner of the lost property has not brought witnesses knowing his lost property, he has lied, he has stirred up strife, he shall be put to death.

§ 14. If a man has stolen the [underage] son of a freeman, he shall be put to death.

§ 15. If a man has caused either a palace slave or palace maid, or a slave of a poor man or a poor man’s maid, to go out of the gate, he shall be put to death.

§ 16. If a man has harboured in his house a manservant or a maidservant, fugitive from the palace, or a poor man, and has not produced them at the demand of the commandant, the owner of that house shall be put to death.

§ 17. If a man has captured either a manservant or a maidservant, a fugitive, in the open country and has driven him back to his master, the owner of the slave shall pay him two shekels of silver.

§ 20. If the slave has fled from the hand of his captor, that man shall swear by the name of God, to the owner of the slave, and shall go free.

§ 21. If a man has broken into a house, one shall kill him before the breach and bury him in it (?).

§ 109. If a wine merchant has collected a riotous assembly in her house and has not seized those rioters and driven them to the p. 20palace, that wine merchant shall be put to death.

§ 129. If the wife of a man has been caught in lying with another male, one shall bind them and throw them into the waters. If the owner of the wife would save his wife or the king would save his servant (he may).

§ 130. If a man has forced the wife of a man who has not known the male and is dwelling in the house of her father, and has lain in her bosom and one has caught him, that man shall be killed, the woman herself shall go free.

§ 131. If the wife of a man her husband has accused her, and she has not been caught in lying with another male, she shall swear by God and shall return to her house.

§ 133. If a man has been taken captive and in his house there is maintenance, his wife has gone out from her house and entered into the house of another, because that woman has not guarded her body, and has entered into the house of another, one shall put that woman to account and throw her into the waters.

§ 134. If a man has been taken captive and in his house there is no maintenance, and his wife has entered into the house of another, that woman has no blame.

§ 138. If a man has put away his bride who has not borne him children, he shall give her money as much as her dowry, and shall pay her the marriage portion which she brought from her father’s house, and shall put her away.

§ 141. If the wife of a man who is living in the house of her husband has set her face to go out and has acted the fool, has wasted her house, has belittled her husband, one shall put her to account, and if her husband has said, ‘I put her away,’ he shall put her away and she shall go her way, he shall not give her anything for her divorce. If her husband has p. 28not said ‘I put her away,’ her husband shall marry another woman, that woman as a maidservant [slave] shall dwell in the house of her husband.

§ 142. If a woman hates her husband and has said ‘Thou shalt not possess me,’ one shall enquire into her past what is her lack, and if she has been economical and has no vice, and her husband has gone out and greatly belittled her, that woman has no blame, she shall take her marriage portion and go off to her father’s house.

§ 143. If she has not been economical, a goer about, has wasted her house, has belittled her husband, that woman one shall throw her into the waters.

§ 152. If from the time that that woman entered into the house of the man a debt has come upon them, both together they shall answer the merchant.

§ 154. If a man has known his daughter, that man one shall expel from the city.

§ 157. If a man, after his father, has lain in the bosom of his mother, one shall burn them both of them together.

§ 162. If a man has married a wife and she has borne him children, and that woman has gone to her fate, her father shall have no claim on her marriage portion, her marriage portion is her children’s forsooth.

§ 168. If a man has set his face to cut off his son, has said to the judge ‘I will cut off my son,’ the judge shall enquire into his reasons, and if the son has not committed a heavy crime which cuts off from sonship, the father shall not cut off his son from sonship.

§ 192. If a son of a palace warder, or of a vowed woman, to the father that brought him up, and the mother that brought him up, has said ‘thou art not my father, thou art not my mother,’ one shall cut out his tongue.

§ 195. If a man has struck his father, his hands one shall cut off.

§ 196. If a man has caused the loss of a gentleman’s eye, his eye one shall cause to be lost.

§ 197. If he has shattered a gentleman’s limb, one shall shatter his limb.

§ 198. If he has caused a poor man to lose his eye or shattered a poor man’s limb, he shall pay one mina of silver.

§ 199. If he has caused the loss of the eye of a gentleman’s servant or has shattered the limb of a gentleman’s servant, he shall pay half his price.

§ 200. If a man has made the tooth of a man that is his equal to fall out, one shall make his tooth fall out.

p. 44§ 201. If he has made the tooth of a poor man to fall out, he shall pay one-third of a mina of silver.

§ 209. If a man has struck a gentleman’s daughter and caused her to drop what is in her womb, he shall pay ten shekels of silver for what was in her womb.

§ 210. If that woman has died, one shall put to death his daughter.

§ 213. If he has struck a gentleman’s maidservant and caused her to drop that which is in her womb, he shall pay two shekels of silver.

§ 214. If that maidservant has died, he shall pay one-third of a mina of silver.

§ 218. If the doctor has treated a gentleman for a severe wound with a lancet of bronze and has caused the gentleman to die, or has opened an abscess of the eye for a gentleman with the bronze lancet and has caused the loss of the gentleman’s eye, one shall cut off his hands.

§ 219. If a doctor has treated the severe wound of a slave of a poor man with a bronze lancet and has caused his death, he shall render slave for slave.

§ 229. If a builder has built a house for a man and has not made strong his work, and the house he built has fallen, and he has caused the death of the owner of the house, that builder shall be put to death.

§ 232. If he has caused the loss of goods, he shall render back whatever he has caused the loss of, and because he did not make strong the house he built, and it fell, from p. 49his own goods he shall rebuild the house that fell.

§ 282. If a slave has said to his master ‘Thou art not my master,’ as his slave one shall put him to account and his master shall cut off his ear.

Project Gutenberg. (September 27, 2017). The Oldest Code of Laws in the World, by Hammurabi, King of Babylon, Translated by C.H.W. Johns. Retrieved from http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/17150

Additional resources:

Feature from the Louvre on the Stele

Dr. Senta German, “Hammurabi: The king who made the four quarters of the earth obedient,” in Smarthistory, August 8, 2015, accessed February 6, 2017, https://smarthistory.org/hammurabi-the-king-who-made-the-four-quarters-of-the-earth-obedient/

Another law code was the Hebraic Torah, including the Ten Commandments (note that there are differences in presentation between Jewish and Christian traditions). Some scholars believe that the Law Code of Hammurabi influenced the Ten Commandments, and other Hebraic laws, which follow. What are some similarities and differences? To what degree do punishments for similar crimes align or differ?

Exodus

Chapter 20

20:3 Thou shalt have no other gods before me.

20:4 Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image, or any likeness of any thing that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth.

20:5 Thou shalt not bow down thyself to them, nor serve them: for I the LORD thy God am a jealous God, visiting the iniquity of the fathers upon the children unto the third and fourth generation of them that hate me; 20:6 And shewing mercy unto thousands of them that love me, and keep my commandments.

20:7 Thou shalt not take the name of the LORD thy God in vain; for the LORD will not hold him guiltless that taketh his name in vain.

20:8 Remember the sabbath day, to keep it holy.

20:9 Six days shalt thou labour, and do all thy work: 20:10 But the seventh day is the sabbath of the LORD thy God: in it thou shalt not do any work, thou, nor thy son, nor thy daughter, thy manservant, nor thy maidservant, nor thy cattle, nor thy stranger that is within thy gates: 20:11 For in six days the LORD made heaven and earth, the sea, and all that in them is, and rested the seventh day: wherefore the LORD blessed the sabbath day, and hallowed it.

20:12 Honour thy father and thy mother: that thy days may be long upon the land which the LORD thy God giveth thee.

20:13 Thou shalt not kill [murder].

20:14 Thou shalt not commit adultery.

20:15 Thou shalt not steal.

20:16 Thou shalt not bear false witness against thy neighbour.

20:17 Thou shalt not covet thy neighbour’s house, thou shalt not covet thy neighbour’s wife, nor his manservant, nor his maidservant, nor his ox, nor his ass, nor any thing that is thy neighbour’s.

As we read further, there are not just commandments, but consequences. Laws help organize society and behaviors. Why do humans need organization? How are our laws similar to (or different from) these two ancient law codes? What ethical or cultural values can we identify in these laws?

20:18 And all the people saw the thunderings, and the lightnings, and the noise of the trumpet, and the mountain smoking: and when the people saw it, they removed, and stood afar off.

20:19 And they said unto Moses, Speak thou with us, and we will hear: but let not God speak with us, lest we die.

20:20 And Moses said unto the people, Fear not: for God is come to prove you, and that his fear may be before your faces, that ye sin not.

20:21 And the people stood afar off, and Moses drew near unto the thick darkness where God was.

20:22 And the LORD said unto Moses, Thus thou shalt say unto the children of Israel, Ye have seen that I have talked with you from heaven.

20:23 Ye shall not make with me gods of silver, neither shall ye make unto you gods of gold.

20:24 An altar of earth thou shalt make unto me, and shalt sacrifice thereon thy burnt offerings, and thy peace offerings, thy sheep, and thine oxen: in all places where I record my name I will come unto thee, and I will bless thee.

20:25 And if thou wilt make me an altar of stone, thou shalt not build it of hewn stone: for if thou lift up thy tool upon it, thou hast polluted it.

20:26 Neither shalt thou go up by steps unto mine altar, that thy nakedness be not discovered thereon.

Chapter 21

21:1 Now these are the judgments which thou shalt set before them.

21:2 If thou buy an Hebrew servant [slave], six years he shall serve: and in the seventh he shall go out free for nothing.

21:3 If he came in by himself, he shall go out by himself: if he were married, then his wife shall go out with him.

21:4 If his master have given him a wife, and she have born him sons or daughters; the wife and her children shall be her master’s, and he shall go out by himself.

21:5 And if the servant shall plainly say, I love my master, my wife, and my children; I will not go out free: 21:6 Then his master shall bring him unto the judges; he shall also bring him to the door, or unto the door post; and his master shall bore his ear through with an aul; and he shall serve him forever.

21:7 And if a man sell his daughter to be a maidservant, she shall not go out as the menservants do.

21:8 If she please not her master, who hath betrothed her to himself, then shall he let her be redeemed: to sell her unto a strange nation he shall have no power, seeing he hath dealt deceitfully with her.

21:9 And if he have betrothed her unto his son, he shall deal with her after the manner of daughters.

21:10 If he take him another wife; her food, her raiment, and her duty of marriage, shall he not diminish.

21:11 And if he do not these three unto her, then shall she go out free without money.

21:12 He that smiteth a man, so that he die, shall be surely put to death.

21:13 And if a man lie not in wait, but God deliver him into his hand; then I will appoint thee a place whither he shall flee.

21:14 But if a man come presumptuously upon his neighbour, to slay him with guile; thou shalt take him from mine altar, that he may die.

21:15 And he that smiteth his father, or his mother, shall be surely put to death.

21:16 And he that stealeth a man, and selleth him, or if he be found in his hand, he shall surely be put to death.

21:17 And he that curseth his father, or his mother, shall surely be put to death.

21:18 And if men strive together, and one smite another with a stone, or with his fist, and he die not, but keepeth his bed: 21:19 If he rise again, and walk abroad upon his staff, then shall he that smote him be quit: only he shall pay for the loss of his time, and shall cause him to be thoroughly healed.

21:20 And if a man smite his servant, or his maid, with a rod, and he die under his hand; he shall be surely punished.

21:21 Notwithstanding, if he continue a day or two, he shall not be punished: for he is his money.

21:22 If men strive, and hurt a woman with child, so that her fruit depart from her, and yet no mischief follow: he shall be surely punished, according as the woman’s husband will lay upon him; and he shall pay as the judges determine.

21:23 And if any mischief follow, then thou shalt give life for life, 21:24 Eye for eye, tooth for tooth, hand for hand, foot for foot, 21:25 Burning for burning, wound for wound, stripe for stripe.

21:26 And if a man smite the eye of his servant, or the eye of his maid, that it perish; he shall let him go free for his eye’s sake.

21:27 And if he smite out his manservant’s tooth, or his maidservant’s tooth; he shall let him go free for his tooth’s sake.

21:28 If an ox gore a man or a woman, that they die: then the ox shall be surely stoned, and his flesh shall not be eaten; but the owner of the ox shall be quit.

21:29 But if the ox were wont to push with his horn in time past, and it hath been testified to his owner, and he hath not kept him in, but that he hath killed a man or a woman; the ox shall be stoned, and his owner also shall be put to death.

21:30 If there be laid on him a sum of money, then he shall give for the ransom of his life whatsoever is laid upon him.

21:31 Whether he have gored a son, or have gored a daughter, according to this judgment shall it be done unto him.

Chapter 22

22:1 If a man shall steal an ox, or a sheep, and kill it, or sell it; he shall restore five oxen for an ox, and four sheep for a sheep.

22:2 If a thief be found breaking up, and be smitten that he die, there shall no blood be shed for him.

22:3 If the sun be risen upon him, there shall be blood shed for him; for he should make full restitution; if he have nothing, then he shall be sold for his theft.

22:4 If the theft be certainly found in his hand alive, whether it be ox, or ass, or sheep; he shall restore double.

22:5 If a man shall cause a field or vineyard to be eaten, and shall put in his beast, and shall feed in another man’s field; of the best of his own field, and of the best of his own vineyard, shall he make restitution.

22:6 If fire break out, and catch in thorns, so that the stacks of corn, or the standing corn, or the field, be consumed therewith; he that kindled the fire shall surely make restitution.

22:7 If a man shall deliver unto his neighbour money or stuff to keep, and it be stolen out of the man’s house; if the thief be found, let him pay double.

22:8 If the thief be not found, then the master of the house shall be brought unto the judges, to see whether he have put his hand unto his neighbour’s goods.

22:9 For all manner of trespass, whether it be for ox, for ass, for sheep, for raiment, or for any manner of lost thing which another challengeth to be his, the cause of both parties shall come before the judges; and whom the judges shall condemn, he shall pay double unto his neighbour.

22:10 If a man deliver unto his neighbour an ass, or an ox, or a sheep, or any beast, to keep; and it die, or be hurt, or driven away, no man seeing it: 22:11 Then shall an oath of the LORD be between them both, that he hath not put his hand unto his neighbour’s goods; and the owner of it shall accept thereof, and he shall not make it good.

22:12 And if it be stolen from him, he shall make restitution unto the owner thereof.

22:13 If it be torn in pieces, then let him bring it for witness, and he shall not make good that which was torn.

22:14 And if a man borrow ought of his neighbour, and it be hurt, or die, the owner thereof being not with it, he shall surely make it good.

22:15 But if the owner thereof be with it, he shall not make it good: if it be an hired thing, it came for his hire.

22:16 And if a man entice a maid that is not betrothed, and lie with her, he shall surely endow her to be his wife.

22:17 If her father utterly refuse to give her unto him, he shall pay money according to the dowry of virgins.

22:18 Thou shalt not suffer a witch to live.

22:19 Whosoever lieth with a beast shall surely be put to death.

22:20 He that sacrificeth unto any god, save unto the LORD only, he shall be utterly destroyed.

22:21 Thou shalt neither vex a stranger, nor oppress him: for ye were strangers in the land of Egypt.

22:22 Ye shall not afflict any widow, or fatherless child.

22:23 If thou afflict them in any wise, and they cry at all unto me, I will surely hear their cry; 22:24 And my wrath shall wax hot, and I will kill you with the sword; and your wives shall be widows, and your children fatherless.

22:25 If thou lend money to any of my people that is poor by thee, thou shalt not be to him as an usurer, neither shalt thou lay upon him usury.

22:26 If thou at all take thy neighbour’s raiment to pledge, thou shalt deliver it unto him by that the sun goeth down: 22:27 For that is his covering only, it is his raiment for his skin: wherein shall he sleep? and it shall come to pass, when he crieth unto me, that I will hear; for I am gracious.

22:28 Thou shalt not revile the gods, nor curse the ruler of thy people.

22:29 Thou shalt not delay to offer the first of thy ripe fruits, and of thy liquors: the firstborn of thy sons shalt thou give unto me.

22:30 Likewise shalt thou do with thine oxen, and with thy sheep: seven days it shall be with his dam; on the eighth day thou shalt give it me.

22:31 And ye shall be holy men unto me: neither shall ye eat any flesh that is torn of beasts in the field; ye shall cast it to the dogs.

Chapter 23

23:1 Thou shalt not raise a false report: put not thine hand with the wicked to be an unrighteous witness.

23:2 Thou shalt not follow a multitude to do evil; neither shalt thou speak in a cause to decline after many to wrest judgment: 23:3 Neither shalt thou countenance a poor man in his cause.

23:4 If thou meet thine enemy’s ox or his ass going astray, thou shalt surely bring it back to him again.

23:5 If thou see the ass of him that hateth thee lying under his burden, and wouldest forbear to help him, thou shalt surely help with him.

23:6 Thou shalt not wrest the judgment of thy poor in his cause.

23:7 Keep thee far from a false matter; and the innocent and righteous slay thou not: for I will not justify the wicked.

23:8 And thou shalt take no gift: for the gift blindeth the wise, and perverteth the words of the righteous.

23:9 Also thou shalt not oppress a stranger: for ye know the heart of a stranger, seeing ye were strangers in the land of Egypt.

23:10 And six years thou shalt sow thy land, and shalt gather in the fruits thereof: 23:11 But the seventh year thou shalt let it rest and lie still; that the poor of thy people may eat: and what they leave the beasts of the field shall eat. In like manner thou shalt deal with thy vineyard, and with thy oliveyard.

23:12 Six days thou shalt do thy work, and on the seventh day thou shalt rest: that thine ox and thine ass may rest, and the son of thy handmaid, and the stranger, may be refreshed.

23:13 And in all things that I have said unto you be circumspect: and make no mention of the name of other gods, neither let it be heard out of thy mouth.

23:14 Three times thou shalt keep a feast unto me in the year.

23:15 Thou shalt keep the feast of unleavened bread: (thou shalt eat unleavened bread seven days, as I commanded thee, in the time appointed of the month Abib; for in it thou camest out from Egypt: and none shall appear before me empty:) 23:16 And the feast of harvest, the firstfruits of thy labours, which thou hast sown in the field: and the feast of ingathering, which is in the end of the year, when thou hast gathered in thy labours out of the field.

23:17 Three items in the year all thy males shall appear before the LORD God.

23:18 Thou shalt not offer the blood of my sacrifice with leavened bread; neither shall the fat of my sacrifice remain until the morning.

23:19 The first of the firstfruits of thy land thou shalt bring into the house of the LORD thy God. Thou shalt not seethe a kid in his mother’s milk.

23:20 Behold, I send an Angel before thee, to keep thee in the way, and to bring thee into the place which I have prepared.

23:21 Beware of him, and obey his voice, provoke him not; for he will not pardon your transgressions: for my name is in him.

23:22 But if thou shalt indeed obey his voice, and do all that I speak; then I will be an enemy unto thine enemies, and an adversary unto thine adversaries.

Project Gutenberg. (February 9, 2017). The King James Version of the Bible. Retrieved from http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/10?msg=welcome_stranger#The_Second_Book_of_Moses_Called_Exodus. . Used under GNU Free Documentation License 1.2

Much of Assyrian art deals with the strength, power, and victories of their kings. Why is it important for humans to have heroes and strong leaders? How do depictions of heroes reveal particular cultural values?

Assyrian art, an introduction

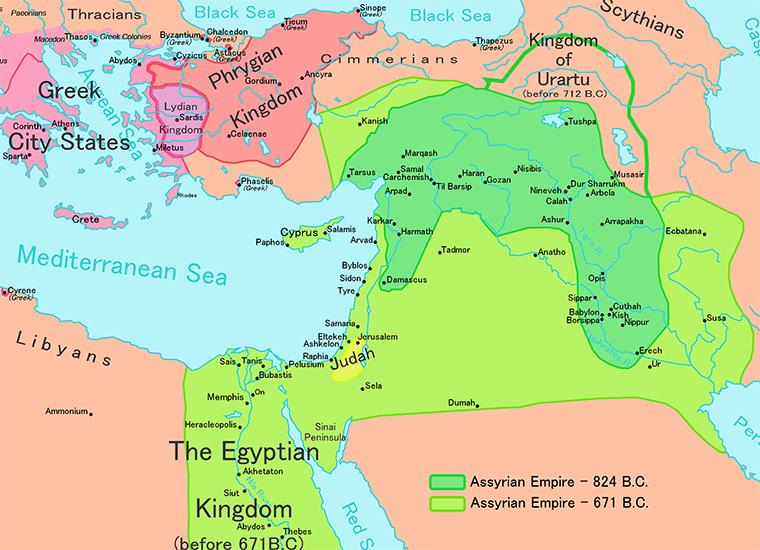

Map of the Neo-Assyrian Empire and its expansions.

A military culture

The Assyrian empire dominated Mesopotamia and all of the Near East for the first half of the first millennium, led by a series of highly ambitious and aggressive warrior kings. Assyrian society was entirely military, with men obliged to fight in the army at any time. State offices were also under the purview of the military.

Ashurbanipal slitting the throat of a lion from his chariot (detail), Ashurbanipal Hunting Lions, gypsum hall relief from the North Palace, Ninevah, c. 645-635 B.C.E., excavated by H. Rassam beginning in 1853 (British Museum)

Indeed, the culture of the Assyrians was brutal, the army seldom marching on the battlefield but rather terrorizing opponents into submission who, once conquered, were tortured, raped, beheaded, and flayed with their corpses publicly displayed. The Assyrians torched enemies’ houses, salted their fields, and cut down their orchards.

Luxurious palaces

As a result of these fierce and successful military campaigns, the Assyrians acquired massive resources from all over the Near East which made the Assyrian kings very rich. The palaces were on an entirely new scale of size and glamour; one contemporary text describes the inauguration of the palace of Kalhu, built by Assurnasirpal II (who reigned in the early 9th century), to which almost 70,000 people were invited to banquet.

Lion pierced with arrows (detail), Lion Hunts of Ashurbanipal (ruled 669-630 B.C.E.), c. 645 B.C.E., gypsum,Neo-Assyrian, hall reliefs from Palace at Ninevah across the Tigris from present day Mosul, Iraq (British Museum)

Some of this wealth was spent on the construction of several gigantic and luxurious palaces spread throughout the region. The interior public reception rooms of Assyrian palaces were lined with large scale carved limestone reliefs which offer beautiful and terrifying images of the power and wealth of the Assyrian kings and some of the most beautiful and captivating images in all of ancient Near Eastern art.

Digital Reconstruction of the Northwest Palace, Nimrud, Assyria

This silent video reconstructs the Northwest Palace of Ashurnasirpal II at Nimrud (near modern Mosul in northern Iraq) as it would have appeared during his reign in the ninth century B.C.E. The video moves from the outer courtyards of the palace into the throne room and beyond into more private spaces, perhaps used for rituals.( Video from The Metropolitan Museum of Art) According to news sources, this important archaeological site was destroyed with bulldozers in March 2015 by the militants who occupy large portions of Syria and Iraq.

Feats of bravery

Ashurbanipal taking aim at a lion (detail), Lion Hunts of Ashurbanipal (ruled 669-630 B.C.E.), c. 645 B.C.E., gypsum,Neo-Assyrian, hall reliefs from Palace at Ninevah across the Tigris from present day Mosul, Iraq (British Museum)

Like all Assyrian kings, Ashurbanipal decorated the public walls of his palace with images of himself performing great feats of bravery, strength and skill. Among these he included a lion hunt in which we see him coolly taking aim at a lion in front of his charging chariot, while his assistants fend off another lion attacking at the rear.

Sacking of Susa by Ashurbanipal, North Palace, Nineveh, 647 B.C.E.

The destruction of Susa

One of the accomplishments Ashurbanipal was most proud of was the total destruction of the city of Susa.

In this relief, we see Ashurbanipal’s troops destroying the walls of Susa with picks and hammers while fire rages within the walls of the city.

Military victories & exploits

Wall relief from Nimrud, the sieging of a city, likely in Mesopotamia, c. 728 B.C.E. (British Museum)

In the Central Palace at Nimrud, the Neo-Assyrian king Tiglath-pileser III illustrates his military victories and exploits, including the siege of a city in great detail.

In this scene we see one soldier holding a large screen to protect two archers who are taking aim. The topography includes three different trees and a roaring river, most likely setting the scene in and around the Tigris or Euphrates rivers.

Additional resources:

Assyria on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Timeline of Art History

Ancient Near East on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Timeline of Art History

Dr. Senta German, “Assyrian art, an introduction,” in Smarthistory, August 8, 2015, accessed February 6, 2017, https://smarthistory.org/assyrian-art-an-introduction/.