4.7 The Early Archaic Period

The Geometric Period in Greek art was followed by a period of eastern influence, sometimes called the “Orientalizing” period. This period took place between 750 and 600 BCE. During this time, trade increased and the Phonetic alphabet arrived to enhance the Greek culture that was developing on the mainland. The stories of the Trojan War had been passed on verbally before writing came to the mainland. This transition period is also when The Iliad and The Odyssey were written down and codified. Due to increase in trade and travel, early Archaic art developed in a new direction. The art of Egypt, as well as the art of the Etruscans, made a strong impression on the Hellenic (Greek) people.

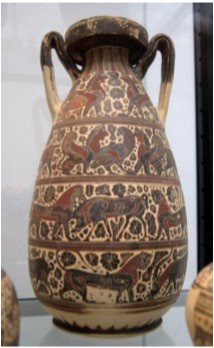

Black figure painting was developed in Corinth using a method of painting with clay slip, a nearly liquid clay, on the orange clay which was found near Athens. The slip turned black when the pottery was fired, creating a stunning contrast between the painted areas and the naturally orange clay. It quickly became popular and spread throughout the area that would become Greece. Fanciful creatures and exotic plants take the place of the geometric patterns of the Mycenaeans. Notice that the painting on this vase imitates a series of friezes on a building. This jug is from a time that is more recent than the period of eastern influence but, it is a perfect example of the pottery of the early Archaic Period. Like earlier Minoan pottery, every space is filled with figures or flowering plant designs. Lions, boars and horses accompany strange bird like griffins or sphinxes, which resemble the Egyptian image of the ba, which is a person’s personality. It is represented by a human headed bird.

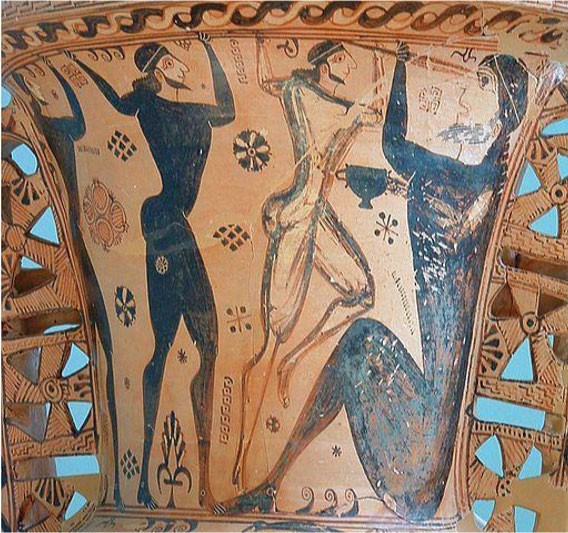

Near Athens this black figure style provided a medium in which to represent mythological stories. This is one of the earliest pieces of pottery to do so.3 As such, human beings are introduced as subject matter. Although they are not terribly naturalistic, they are more so than those in the earlier geometric style.

The Polyphemos amphora depicts a scene from the Odyssey where Odysseus put out the eye of the Cyclops. It demonstrates the use of silhouette with only the face in outline. The bodies resemble those on geometric vessels but they are fuller, livelier and more individual than in the earlier style. Like the vase in image 4.46, every space is filled with design elements. The Athenian orange clay is obvious in this particular vessel.

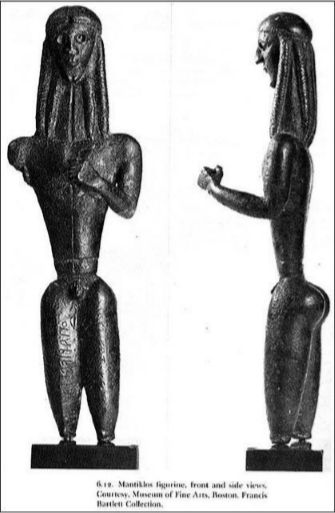

Sculpture was also affected by the new ideas flowing into the area. Image 4.49 is a small bronze statue which at first seems geometric. It is in fact similar to geometric sculpture but there is an indication of movement not seen in the earlier period. Notice that Apollo’s left leg is slightly forward, a position that will be popularized as the Archaic Period continues. His hand has been separated from his chest, creating a more open and inviting image.

It is easy to see the influence of Egypt in this statuette. The hair is plaited (braided) and the image is essentially frontal and formal. The figure steps forward, as male Egyptian sculptures do. The new openness of the statue, however, is not Egyptian. There were probably jewels or stones inset into the eye sockets and all lines lead to the head. That is an indication that reason is becoming an important aspect of the developing culture. Notice also that the Gluteus maximus muscle is exaggerated. This demonstrates that there is pride in the muscular build that comes from walking or riding everywhere. This is the seed of idealism that would soon blossom.

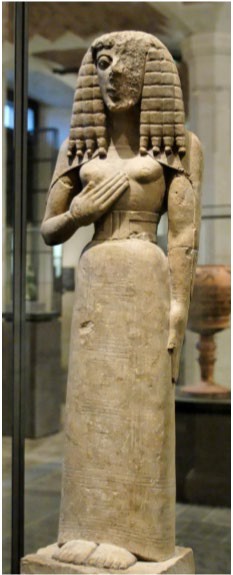

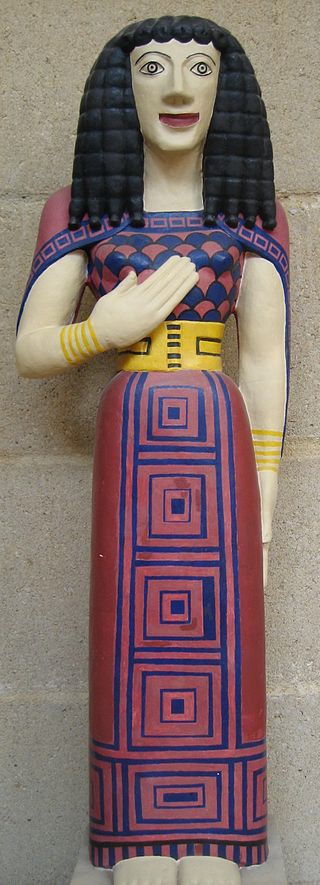

The Lady of Auxerre is a relatively small limestone figure is 26” tall and was probably a votive offering. The statuette demonstrates an Egyptian influence, but she is more open than most Egyptian sculpture. The Lady has the plaited hair often depicted in Egypt as well as the long fingers that are seen in images there. She shares something else with Apollo, however, which is not typically Egyptian. She has a smile on her lips. It may have been borrowed from the neighboring Etruscans. Close inspection reveals that the lady has a pattern incised (carved shallowly) onto her dress. Even the belt around her tiny waist is decorated with texture. The entire figure would have been painted, as can be seen in the reconstruction. Although the skirt of her dress is quite blocky, her upper body is revealed “through” the fabric. Her arms display musculature, unlike earlier Geometric Period figures.

Much of the Egyptian influence, seen above, remains in pottery and sculpture throughout the Archaic period (C. 600 to 480 BCE). As the Classical Period approaches, however, the images become less Egyptian in style and as time moves on a visual Greek identity can be seen.

ARCHAIC ARCHITECTURE

Stone temples were first built during the Archaic period in ancient Greece. Before this, they were constructed out of mud-brick and wood–simple structures that were rectangular or semi-circular in shape–which may have been enhanced with a few columns and a porch. The Archaic stone temples took their essential shape and structure from both these previous wooden temples and the shape of a Mycenaean megaron, which is a rectangular great hall, usually supported with pillars. The impact of cultural interest in reason is already apparent in these structures, which also demonstrate a quickly developing knowledge of building with stone.

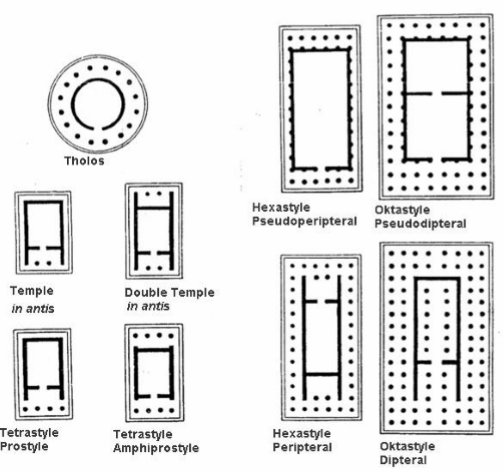

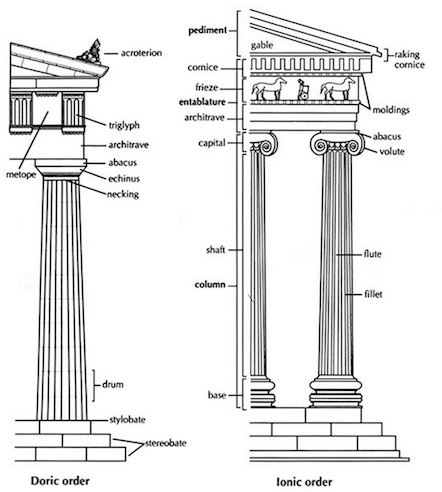

Most temples were in the shape of a rectangle and stood on a raised stone platform known as the stylobate, which usually had two or three steps. One notable exception to this standard was the circular tholos dedicated to Apollo at Delphi. Columns were placed on the edge of the stylobate in a line or colonnade, which was peripteral (surrounded by a single row of columns) and ran around the naos (inner chamber that holds a cult statue) and its porches.

While this describes the standard design of Greek temples, it is not the most common form found. The first stone temples varied significantly as architects and engineers were forced to determine how to properly support a roof with such a wide span. Later architects, such as Iktinos and Kallikrates who designed the Parthenon, tweaked aspects of basic temple structure to better accommodate the cult statue. All temples, however, were built on a mathematical scale and every aspect of the temple is related to the other parts of the temple through ratios. For instance, most Greek temples (except the earliest) followed the equation 2x + 1 = y when determining the number of columns used in the peripteral colonnade. In this equation, x stands for the number of columns across the front, the shorter end, while y designates the columns down the sides. The number of columns used along the length of the temple was twice the number of columns across the front, plus one. Due to these mathematical ratios, we are able to accurately reconstruct temples from small fragments.

PAESTUM, ITALY

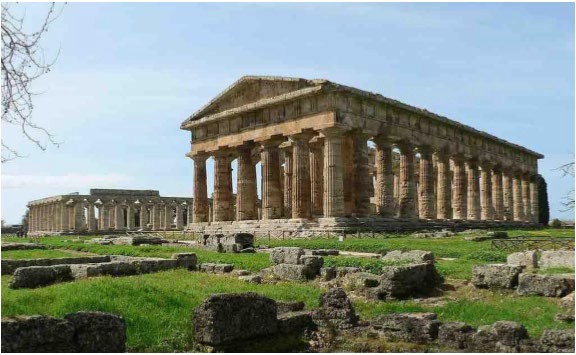

The Greek colony at Poseidonia (now Paestum) in Italy, built two Archaic Doric temples that are still standing today.

The first, the Temple of Hera I, was built in 550 BCE and differs from the standard Greek temple model dramatically. It is peripteral, with nine columns across its short ends and 18 columns along each side. The opisthodomos or rear room of a Greek temple, is accessed through the naos by two doors. There are three columns in antis (posts or pillars at doorway) across the pronaos (front porch of a temple). Inside the naos is a row of central columns built to support the roof. The cult statue was placed at the back, in the center, and was blocked from view by the row of columns. When examining the columns, one finds that they are large and heavy, and spaced very close together. This further denotes the Greeks’ early unease with building in stone and the need to properly support a stone entablature and heavy roof. The capitals of the columns are round, flat, and pancake-like.

The Temple of Hera II, built almost a century later in 460 BCE, began to show the structural changes that demonstrated the Greek’s comfort and developing understanding of building in stone, as well as the beginnings of a Classical temple style. In this example, at the front of the temple are six columns, with fourteen columns along its length. The opisthodomos was separated from the naos and had its own entrance and set of columns in antis. A central flight of stairs led from the pronaos to the naos and the doors opened to look upon a central cult statue. There were still interior columns; however they were moved to the side, permitting prominent display of the cult statue.

Attributions:

“Temple Architecture in the Archaic Greek Period.” Boundless Resources. Art History Hub. Modified by T. Kate Pagel, PhD for, “Early Archaic Period.” Humanities: New Meaning From the Ancient World. Colorado Springs, CO: Pikes Peak Community College, 2020. CC BY-NC 4.0 License. Available: http://oer2go.org/mods/en-boundless/www.boundless.com/art- history/textbooks/boundless-art-history-textbook/ancient-greece-6/the-archaic-period- 64/temple-architecture-in-the- greek-archaic-period-332-10516/index.html. [Accessed: 13-Jan- 2020]

References:

1. Photo by: Wikimedia, License, CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Corinthian_jug_animal_frieze_580_BC_Staatliche_Antikensammlunge n.jpg.

2. Photo by John Lee, Nationalmuseet, Germany. CC BY-SA 2.5 https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?search=Egyptian+ba&title=Special%3ASearch&go=Go&ns0=1&ns6=1& ns12=1&ns14=1&ns100=1&ns106=1#/media/File:Ba-fugl_AS-6585_original.jpg

3. Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polyphemos_Painter. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

4. 511px-Polyphemus_Eleusis_2630.jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1353019. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

5. Provided by: Flickr. Located at: https://www.flickr.com/photos/47357563@N06/7953461862. License: CC BY: Attribution.

6. Photo by Jastrow, CC By 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Lady_of_Auxerre_Louvre_Ma3098_n1.jpg

7. Photo by Neddyseagoon, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Lady_of_Auxerre_University_of_Cambridge.jpg

8. “Temple types.” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Temple_types.gifWikipedia CC BY-SA.

9. https://smarthistory.org/introduction-to-greek-architecture/

10. “Veduta di Paestum 2010.” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Veduta_di_Paestum_2010.jpgWikipedia CC BY-SA.