1.4 SCULPTURE IN PALEOLITHIC CULTURE

The Venus of Willendorf

Drawing inspiration from the above figurine made by a PPSC student, hold the figurine shown below [from three angles, in images 1.24, 1.25 and 1.26] in the palm of your hand. In your imagination, caress her. Appreciate how she nestles into the softness of your hand and your fingers curl around her. Let your thumb stroke her head. With your other hand pass your fingers over her pendulous breasts, her ample abdomen and her carefully defined pubic area. Where are her hands? What is special about her hair?

You are meeting a Paleolithic figure known as the Venus of Willendorf. She was named for the location of her 1908 discovery above the Danube River, near the town of Willendorf in western Austria. She now resides in the Natural History Museum in Vienna. Carved from non-native stone between 25,000-20,000 BCE, she is only 11.1 cm tall (4 3/8”). She and other prehistoric figures of women are called “Venus” figures in acknowledgment of the Greco-Roman goddess of love.

However, unlike the demurely concealed Classical or Renaissance depiction, most of these prehistoric figures are plump, with exaggerated female characteristics: large breasts, thighs and buttocks. They are found, especially in agricultural societies, all over Europe and America. Many were carved of soft stone, bone or ivory; others were formed of clay and fired, making them among the oldest ceramics known. They are all of a modest, personal size. The Venus of Willendorf is by far the most famous of these Venus figures.

By now you are holding her easily. She feels totally naturalistic. The details depicted in this sculpture are consistent with the physical world as we know it. She certainly is recognizable as a woman, but wait, what’s missing? “She has no face!” She has no identity! “She has no feet!” She won’t be going anywhere; she won’t be working! And her arms are unnaturally thin! The artist, a man or a woman, has added emotional and psychological meaning to this figure, making it a fine example of both Naturalism and Realism.

Let’s look at how specific Elements of Art suggest both Naturalism and Realism.

What types of lines do you see and where do you see them? Are the lines, or the implied lines, vertical, horizontal, diagonal, curved or straight? Obviously, the curved lines of her breasts and thighs are significant. Look again at the curls in her hair, or perhaps we are looking at horizontal bands of braided or plaited hair, or perhaps she was wearing a woven cap [image 1.27]. She may be static, in repose. But curved lines make our eyes move, suggesting life. Isn’t that possibly why she felt so realistically powerful as you held her in your hand?

What shapes do you observe? Remember, shapes are closed lines. Because sculpture has height, width and depth, shapes are identified as form. To me, the rounded forms of her body, which could be seen geometrically as cones or spheres, suggest her health, and perhaps her status in society. Would you agree, or do you think she is too fat to successfully gather food?

The texture of this figurine gives rise to some curious possibilities. Her navel is thought to have been a natural indentation in the stone. Did that possibly suggest some topical ideas to the artist? As I hold her, I can feel the hard work of using a piece of flint to carve her out of a piece of oolithic limestone, and then the additional work of smoothing her by sanding her with other rocks so that my tactile sensation does not detract from the function of the sculpture.

By the way, the stone from which she was made is not indigenous to this part of Austria! So the material from which she was made, the media, was imported. Either the carved image was brought in from elsewhere, or the oolithic limestone was imported. What else do you suppose they were trading? Furs, amber, shells and flint blades are a few good possibilities.

And what might we surmise from the color? When she was discovered there were still traces of red ochre on her. Doesn’t that red have a powerful emotional, psychological, and physiological meaning?

These Elements of Art, in addition to the Cultural Context Values, bring us to the most important question: what might have been the function of this work? Portable sculpted works of art are known as mobiliary art, and her personalized size might have been significant. To me, her gender role seems to have been strongly reinforced. She might have been an image of beauty, or a guardian figure, or a goddess. Others suggest she was merely a doll, just A Woman of Willendorf. I prefer to wonder, in the way of a Humanities instructor, was this an attempt to explain the mystery, and tragedy, of life?

Unfortunately, like other Paleolithic art, we have no written documents—so your guesses are as good as mine!

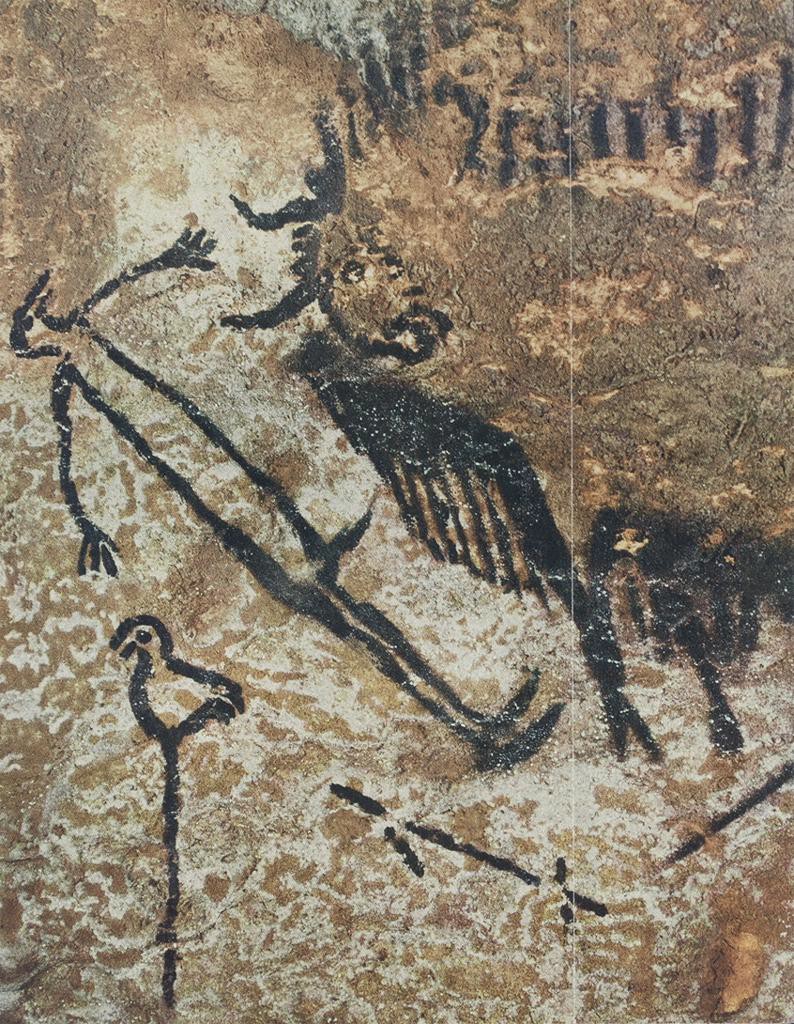

While we’re discussing the Elements of Art, let’s make one last comparison. The dominant lines and shapes of these two Paleolithic subjects are diametrically opposite. The weak stick figure of the Man at the Well [image 1.28] was made of straight lines and a collection of square shapes, making a rectangle. Cars are linear: when driving you go to and return from something. We often live in a house with four corners. Squares are Cartesian, they are rational; they are made with Euclidian theorems. The square, or the rectangle, in art will represent humankind’s physical aspirations. On the other hand, a circle suggests wholeness, completeness and continuity [image 1.29]. As a field of grain returns to complete the cycle of life, so does human life. The circle, therefore, represents our spiritual aspirations. You will see this recurring comparison in Greek and Roman architecture, as well as in Gothic examples.

I can’t make the Venus “come alive” in your hand, but this link a video by the Khan Academy does a pretty good job.

References:

1. Figurine inspired by the Venus of Willendorf by PPCC student Eddy Valkonen, 2010. Photo by the author, Kathleen J. Hartman, 2019. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

2. Aiwok [CC BY-SA 3.0 (creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)]

3. © Jorge Royan / www.royan.com.ar

4. User: Matthias Kabel [CC BY-SA 3.0 (creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/)]

5. Public domain at search.creativecommons.org/photos/a6a2eb18-4aa3-48e4-a570-5c294bcc7a20

6. Cropped from Mary Beth Looney, “Hall of Bulls, Lascaux,” in Smarthistory, November 19, 2015, accessed August 16, 2019, smarthistory.org/hall-of-bulls-lascaux/

7. User: Matthias Kabel [CC BY-SA 3.0 (creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/)]