1.2 Painting in Paleolithic Culture at Lascaux Cave, Dordogne, France

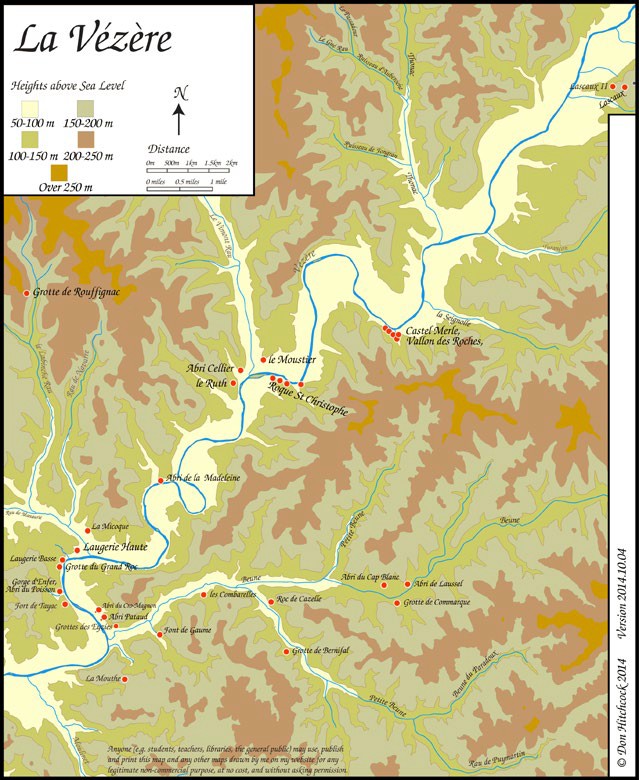

In the late 1930s a giant pine tree fell in the Dordogne region of southwest France. [Images 1.2 and 1.3], exposing an enticing hole. On a September afternoon shortly thereafter, Marcel Ravidat, Jacqueset Marsal, Georges Agnel and Simon Cencas were out exploring in this area with their dog. As “Robot” sniffed around he suddenly slipped into that hole. “Woof. Woof!” Fourteen-year old boys would certainly not abandon Robot. The event was recounted by one of the boys who found the Lascaux Cave on September 12, 1940:

Suddenly we found a hole. We moved a few stones to make the opening wider. Because I was the strongest, I was the first to climb down into the darkness. I was afraid to start with, because you never know what’s lurking in a cave. But my burning curiosity overcame my fear of the unknown. Still, my heart was beating furiously. I slipped, tried to hold on to some stones but slid downwards several metres. And then, when I finally came to the bottom I was amazed to see the strangest pictures on the walls.3

Like those boys, upon entering a cave one has the feeling that he or she is entering the womb of the earth. It is damp, and cold, and dark. The space is not lit with floodlights as we enjoy in the above photograph; overwhelmingly, our anxious sensations of superstitious mystery are magnified by the interplay of light from our flickering torches. In Paleolithic (“old stone”) days light from stone lamps, moving over bumps and crevices, might have suggested fear-inspiring natural shapes and perhaps an illusion of movement. For 5000 years the walls at the Lascaux Cave [image 1.4] were painted over and over again with approximately 600 naturalistic and realistic paintings and another 1500 abstract symbols or designs. This could be the romanticized birthplace of human intelligence, imagination and creative power.

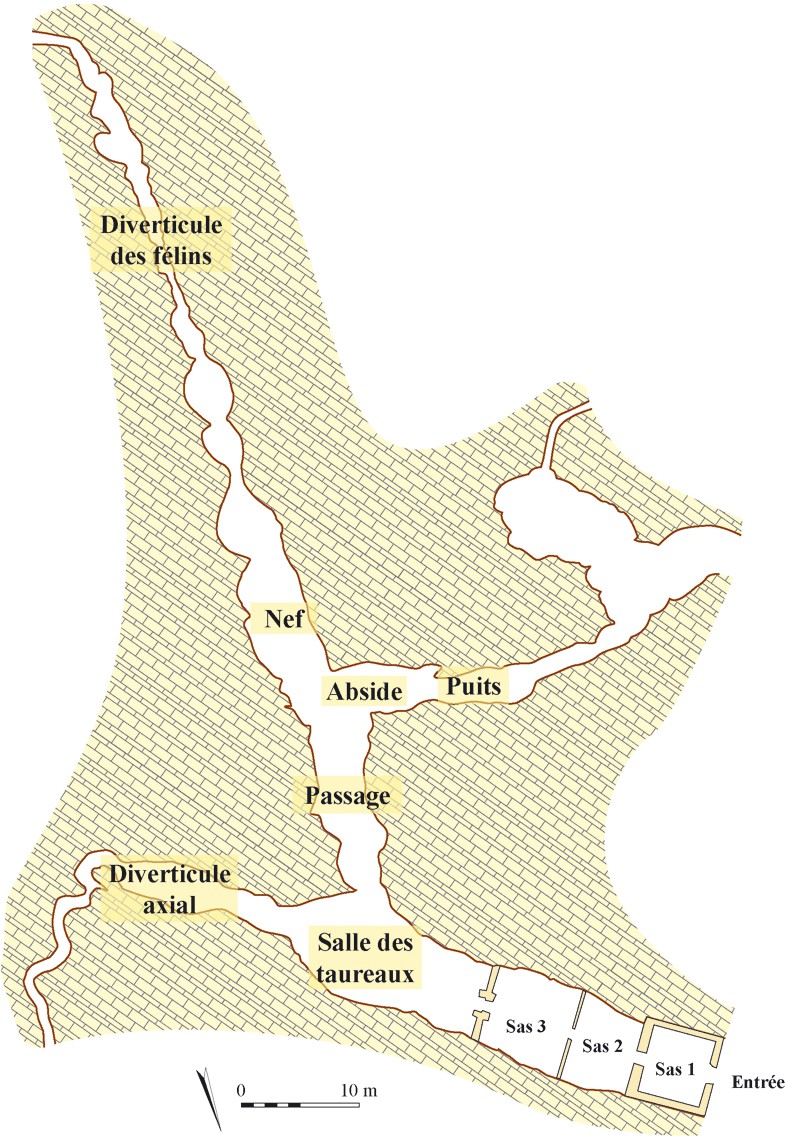

It is not surprising that the artists referred to Naturalism. Those big game hunters were imitating the actual appearance of their world. By depicting the world as it might be seen they were reflecting not only their questions, but also their search for answers. They were seeking to make sense out of this world. In addition to working in dim light, the site was relatively inaccessible. The main hall is approximately 85’ from the entrance [image 1.5]. At sunset on the summer solstice, the sun shines in for about 55 minutes. The full moon could enter on the morning of the winter solstice. For an artist, the lack of light added to the challenge of painting diverse animals with true-to-life details on the irregular surface.

These artists were not limited to naturalistic depictions. They also added Realism, which is more than the apparent representation of things and experiences [image 1.4]. The subject is recognizable and the artist appears to be recording exactly what he or she is seeing, but an emotional or psychological overlay has been added. Even if the depiction represents an imagined or supernatural figure, it has a surface naturalism to which abstraction and expressionistic distortion have been added. Realism may include trompe-l’oeil (fool the eye) and the illusion of perspectival depth.

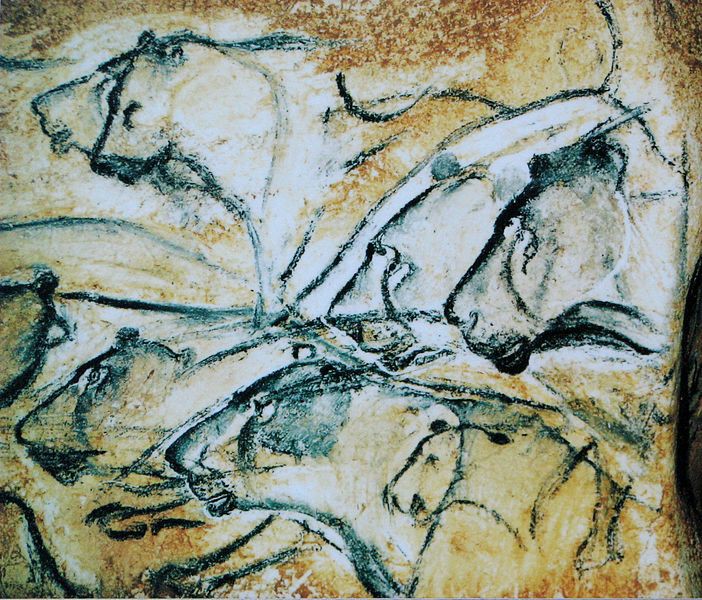

The transformation of a space, as was accomplished in these caves, is known as an installation. As a multimedia presentation the drama of the location might have been accompanied by chanting, singing, prescribed gestures such as dance, and quite likely music. The best acoustics in the cave have been noted in the front where there is art nearby, such as horses, bison and other hoofed animals. In the rear, where sound is dampened, are six engravings of panthers and other stealthy animals. (Unfortunately, this author had no access to clear pictures of these prowling creatures at Lascaux. There are, however, some fine ones on Don Hitchcock’s website. Perhaps these much older lions at Chauvet-Pont-d’Arc, shown in image 1.6, will satisfy your imagination.) An echo made by whistling [image 1.7], or percussive music (such as clapping, slapping on one’s thighs or knocking on stalactites or skulls) might simulate a stampede of these pounding monsters.

Surprisingly in the cave, there is only one complete drawing of a human [image 1.8], and he is at the bottom of an 18’ shaft or well which can only be reached by climbing down a ladder. Because of this location he is known to us as the Man at the Well. The man, depicted with a bird’s head, is shown in an ithyphallic position of power with his spear and a bird on a pole as he faces a disemboweled bison. Behind him is with a wooly rhino, which may or may not have been drawn by the same artist. Is the man, perhaps, a shaman? As a religious specialist the shaman might have understanding of three worlds: the present world of the living, the province of the dead, and the domain of ghosts. Remnants of a three-twined rope were also found in the shaft. The rope might be a remnant from a net, fishing line, thread, woven goods, or basket. Let your imagination run! This scene is more of a narrative; conceivably, a story is being told here. Does he hope to accrue an animal’s power as he straddles the spiritual worlds of animals and humans? Are the human and the animal worlds being linked with the spirit world through his dreams and trances? Is protection being offered through the spirit of the bird’s head on his mask? Does the bird suggest the ascent of the man’s soul? His staff possibly points north. Is that significant?

Most importantly, why was the man not depicted naturalistically? Does the abstract depiction, the dramatic realism, perhaps suggest Spiritualism? Spiritualism does not have the same meaning as “religious.” Spiritualism, used correctly, signifies “communication with the dead through a medium or psyche.” Ouija boards, spirit voices, levitating tables and automatic writing are examples of spiritualism. Or, this is possibly Animism. Animism is the belief that a spirit or force resides within each animate and inanimate object. We still refer to animism today: skies seem ‘threatening,’ seas and fires ‘rage,’ forests ‘murmur,’ and Mother Earth ‘beckons’ us to rest. Or, perhaps, this figure is simply an example of one human’s fear or vulnerability.

The best way to understand the past is through writings and the creations of those who lived in the past. Because the people of prehistory celebrated their accomplishments mostly in an oral tradition, the primary sources of prehistory are not literary. These early sources are to be known through the disciplines of geology, paleontology, anthropology, archaeology and ethnography (cultural anthropology). What is known of Paleolithic life derives largely from paintings found in 147 sites particularly in the Franco-Cantabrian area of southern France and northern Spain. Twenty-five of these caves exhibit parietal art (painting on cave walls). The most famous of these sites is at Lascaux, which has been closed to the public since 1963 due to the destructive growth of algae, bacteria and fungi. However, there are other interesting locations which you might choose to explore. In France these include caves at Chauvet and Pech-Merle caves; in Spain the caves of Altamira and El Castillo; the Blombos cave in South Africa; the Borneo caves in Indonesia; and Mezhirich in the Ukraine.

When you become interested in the past, the choices you make to study will reflect your own times. What is the voice you hear speaking in one of these creations? Bring that voice home, and happy spelunking!

You might appreciate this link to a website in which you can click and drag your mouse (instead of a greased torch) to explore around the cave:

Rousselle, Stefania, Neda Shastri and Kaitlyn Mullin, Lascaux Caves, Paleolithic and New Again. Or, take a visual tour of the cave.

References:

1. Lascaux (Dordogne) France. Mary Beth Looney, “Hall of Bulls, Lascaux,” in Smarthistory, November 19, 2015, accessed August 16, 2019, smarthistory.org/hall-of-bulls-lascaux/

2. Photo by Don Hitchcock at www.donsmaps.com/lascaux.html

3. Quoted by www.coursehero.com/file/27520277/1Prehistory-3Egypt-stdntpptx/.n.d. Web. 28 Aug. 2019.

4. Mary Beth Looney, “Hall of Bulls, Lascaux,” in Smarthistory, November 19, 2015, accessed August 16, 2019, smarthistory.org/hall-of- bulls-lascaux/

5. Permission: GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2.

6. Photo by the author, Kathleen J. Hartman, at the Vienna National Historical Museum, 2010. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

7. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Lions_painting,_Chauvet_Cave_(museum_replica).jpg

8. Lascaux (Dordogne) France. Photo: Don Hitchcock, donsmaps.com