4.12 MUSIC IN THE GREEK CLASSICL AGE

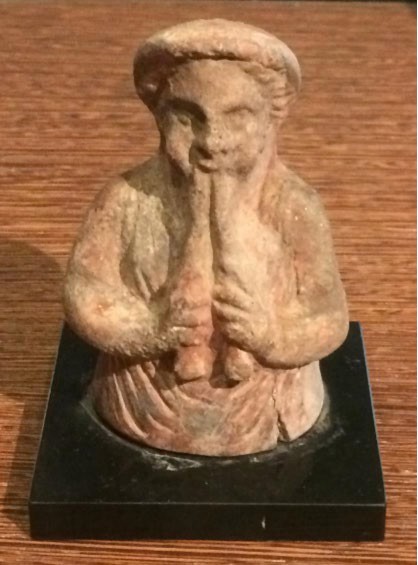

Music was always an important part of Greek culture. Images of musicians appear as early as the Bronze Age Cycladic culture of the Aegean Sea. The aulos, the double flute that was used in Classic tragedy, had changed little since those early images. By the fifth century, Greek education came to include both gymnastics for the body and music for the soul. As the application of reason became more prominent, the philosopher and mathematician, Pythagoras, turned to it in order to codify music and like nearly every other art form, music would be defined and formulated by math.

The Greeks divided their music into modes, each defined by the mood that it evoked. These modes were similar to the modern idea of musical keys. The problem was that these modes and their corresponding melodies could only be taught through repetition. Pythagorus wanted to find a way to codify music so he created a repeatable musical system. He did this through the application of math. Just as the Parthenon and Doryphorus were constructed to be mathematically harmonious, Pythagorus did the same for music.

He discovered that he could coordinate mathematical ratios of melodic intervals with the scale system which he called modes. He demonstrated that the intervals, such as the octave, fifth and fourth, have mathematical relationships. When a tuned string was stopped off at the middle and compared to the same string played without the stop, the interval between determined the octave. The ratio was 1:2. Divide a string into two parts and compare it to a string divided into three parts and the interval between determines a fifth. Likewise when comparing the triply divided string to the string divided into four parts, a fourth is created by the interval between the two, with a ratio of 3:4.2

This system allowed the same type of order to be imposed on music that was imposed on sculpture and architecture.

This order was based on ratios and allowed the logic of music to be identified and duplicated reliably. It could even be

written down and shared with those who, if they knew the system, did not need to meet the composer or have the piece played for them in order to duplicate it.

Since the Greeks thought of immortality as being in tune with cosmic forces, the hope was that at last the individual might hear the music of the spheres. The music of the spheres is related to the golden mean, a mathematically based theoretical measure of all things. This idea assumes that the physical world is in harmony with the metaphysical one. As such, math tied the world’s together, determined beauty, and allowed music, with all of its implications to be more accessible to the Greek mind.

References:

1. Aulos Player, terra cotta. Photo courtesy of Kathleen J. Hartman, CC BY-NC-4.0 License.

2. Fleming, William. Arts and Ideas, eighth edition. Harcourt Brace, College Publishers, New York. 1990