4.13 GREEK CLASSICAL THEATRE

What is theatre? When one hears about theatre many things may come to mind. Is it about actors, special effects or bright lights and song? Today’s theatre incorporates new technologies in lighting, flies actors about the stage and creates entire worlds that enfold the audience. Not that much has changed since the early days of theatre in ancient Greece. The most important purpose of most modern theatre is entertainment. In Classical Athens, where the only existing Classical plays were penned, however, the purposes of theatre were many. Also, like the sculpture of the time, these plays served the Democracy and reflected the values and ideas of Classical Athens.

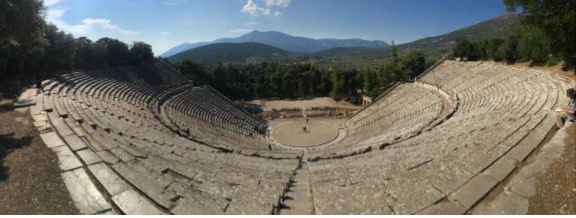

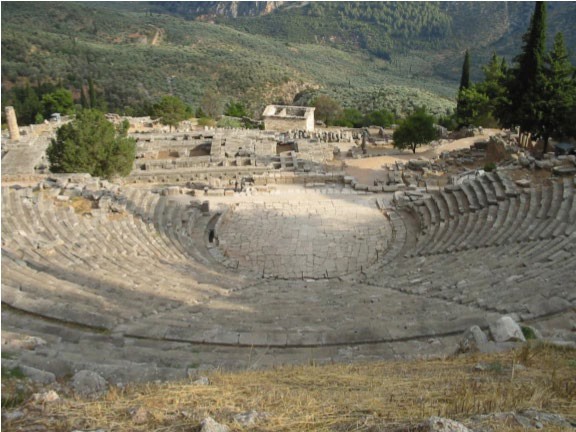

Greek theaters did not have lighting; they were outdoor theaters that used hillsides to serve as seating for up to 15,000 spectators. How could so many people hear the play without microphones or electricity? The hillside works like a band shell to channel the sound to the audience. The “theatron,” was where the audience sat. The term translates as, seeing place.

The spelling, “theater” refers to the structure. The spelling, “theatre” refers to what is experienced there.

Clearly, it was not only important to hear the play but also important to see the action. While Greek theatres did not require lighting, there were special effects, including the use of a crane to fly Medea away in the play named after her.

There are also ancient anecdotes describing the frightening nature of the furies, vengeful spirits in The Euminides that haunt Orestes for killing his mother. It is clear that in addition to the elevated shoes worn to help make actors visible , costumes were also worn. However, entertainment was only one of the many reasons Greek theatre came into existence.

HISTORY

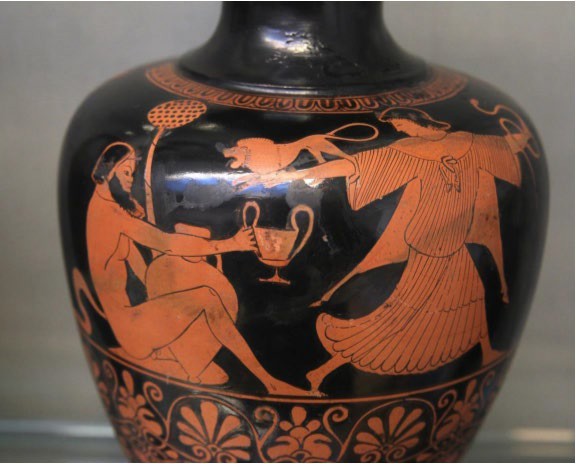

This art form actually began as a yearly contest between two choirs, each singing religious hymns dedicated to Dionysus, the god of wine and revelry. These choirs were referred to as choruses and they could contain as many as fifty singers. During one of these contests in 612 BCE one of the singers stepped forward and spoke lines for one of the characters whose story was being told in song. This speaker’s name was Thespis and since that day, actors have been referred to as thespians. The early plays, many by the poet Aeschylus, only had two speakers on stage at one time.

Sophocles, a later poet, added a third speaker. This was not realistic theatre. The same two or three actors (always male) played all of the speaking roles.

STYLE

How could the audience know which character was which? A mask was worn to identify the speaker and possibly to amplify the voice. Additionally, after each section of dialog, the chorus, now much smaller in number, commented on the action, helping the audience to catch anything they may have missed and aiding in the understanding of the story. These choruses often seemed to have represented the general population of the Democracy. Much like the speaking characters did, the choruses, each with a leader, often debated the issues at hand. The agon, or argument, was the basis of this

theatrical form. It is from this word that we get the term to agonize. The agon is a reflection of the application of reason and of Democracy, both of which were important to Athenians.

This mask is made of terracotta and so would probably have been too heavy for actual use. It does, however, provide an idea of what a mask might have looked like. Note the megaphone shaped mouth, which may have aided in projecting the actor’s voice. Fifth century theatre masks were made of linen on wooden frames. Leather may have been employed as well. It can be shaped when wet. There would have been a recognizable mask for each character that spoke dialogue.

The ancient playwrights considered the music that they wrote to be the most important part of their new plays. It certainly would have been the part that was easiest for the audience to share later when they struck out for their homes. Musical patterns and rhyming words are the easiest ways to remember a long sequence of information. These plays were written as elaborate poems, half of which were sung.

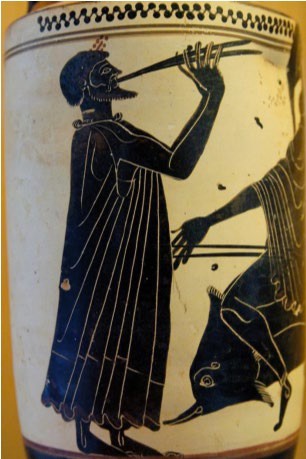

The plots were all drawn from Greek myths so the music was the biggest draw, as the stories were already fairly well known. The playwrights took great pride in the new music that would be presented by the chorus in the center of the orchestra, which is the circular area where the chorus danced and sang. Unfortunately, only a snippet a few seconds long, from one of Euripides’ plays, is still available today. Remember that Pythagorus made writing down music possible.

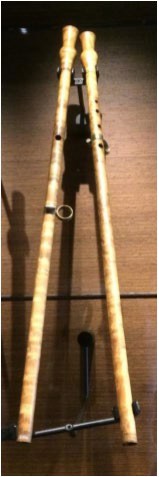

The auolus is dedicated to tragic theatre. A single musician stood at a small altar in the middle of the orchestra and accompanied the chorus on a double- flute called an auolus. It is likely that the mournful sounding instrument was in what would now be considered a minor key. Minor keys tend to make the listener uncomfortable, like the music in horror movies that warn the silly girl not to go in the basement.

PURPOSES OF ANCIENT GREEK THEATRE:

City Dionysia is the name given to the five-day theatre festival dedicated to Dionysus each spring in Athens. As the name suggests, the entire city was a part of the celebration. The first day consisted of a grand procession led by the Choregus, who was a wealthy Athenian that was “volunteered” by city officials to fund the training of the chorus. This gave him the opportunity to achieve immortality and fame. It also helped to keep any one person from controlling too much wealth, as this honor was extremely expensive. The procession that he led was made up of the widows and orphans of all of the brave Athenians that had given their lives for their city-state. In other words, this was a civic, as a well as a religious celebration. It reminded the population, many of whom were only able to make it to Athens once a year, about their duty to the group.

The next three days consisted of viewing the plays. Three tragedies by the same playwright were performed each day. With the exception of Euripides, playwrights acted in their own plays. During the performances, the audience was expected to purge their emotions, which was no doubt encouraged by drinking wine in the sun all day. In this society that sought control of their emotions, theatre provided an outlet, much like watching Oprah Winfrey does today.

Ancient anecdotes indicate that Greek audiences were known to break out into tears. They were noisy and heavily involved in the plays, booing if they did not approve and cheering wildly when they did.

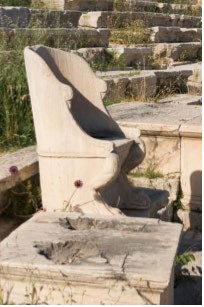

Following the three plays, was a short satire called a saytr play. It was over the top styled comedy. The actors were dressed as satyrs, known for their randy nature. They sported huge phalli, which added humor in a culture that minimized genitalia in their sculpture. Allowing such aspects to rule behavior was humorously inappropriate. The satire gave the playwright an opportunity to spoof his own work and provided the audience a transition from the serious business of watching tragedy. Tragedy was expected to teach the audience. City officials, who sat in the only permanent seating in the space, judged the plays. The viewers were expected to learn about their duties to the Democracy, about their religion and about social expectations of appropriate behavior. The final day was a day of celebration and the prize of a goat, a valuable item, was given to the playwright that was judged to have written the best trilogy of plays.

Two more valuable things that theatre provided were social and economic benefits. This gathering was, for many, the only time in the year that they could take part in their Democracy and meet their fellow citizens. Everyone was welcome at

the plays and they were provided free to any who wished to attend. The festival was held in the spring in order to encourage trade. In the spring the Aegean Sea was navigable, so allies and friends could make it to the city.

GREEK VALUES

Since Greek theatre in Athens was intended to teach and unify the democracy it naturally had specific rules. It is in these rules, as well as in the texts of the plays that the values of idealism, rationalism and humanism can be perceived. This is especially clear in the plays by Sophocles and Aeschylus. However, Euripides, the most modern of the three, seemed to be questioning these very ideals. One could say that while Aeschylus presented things the way that they should be, Euripides presented them the way that they were.

There is a theatre convention (an agreed upon way of doing things) called the three unities, that displays the purposes of theatre and the cultural values associated with it.

Unity of action – This meant that, like Classical sculpture, there was one focus. Only one story line kept the message clear. This is much different than modern sitcoms, which have three or more storylines that conclude in twenty minutes. This is the clarity associated with idealism and is a rational way of creating the opportunity to purge emotions, what great irony. If one is to learn from theatre, the lessons must be clear.

Also, all subject matter had to be drawn from the myths. This not only guaranteed that morals, history and religious duties would be taught, it also kept the audience from fighting about contemporary issues. It is important to note that comedy was not to be mixed into tragedy for the sake of clarity. Unlike comic inventions, tragedy could not be misread.

Unity of place – This meant that there were no set changes to confuse things. All violent action (which is not the ideal way to act) took place offstage and was only shared by messenger characters, often shepherds. This kept the focus on the message and avoided unnecessary distraction. The setting usually consisted of a set of palace doors. All protagonists were expected to be of noble birth so the population could learn from them. The palace doors kept the action focused on the community and provided an additional entrance for actors. Also these important mythical people affect the entire community, as any citizen of a democracy would do.

Unity of time-The action of each play was to take place in real time. In other words, what was seen on stage should be able to happen in the amount of time that the play lasted. This made the action believable and separated it from the epic form of poetry, which could cover long periods of time. Keeping the action in real time involved the viewer, making them concentrate on what they were supposed to be learning. Remember that the primary dialogue of these plays consisted of agons, where the viewer became embroiled in the argument, causing them to think about the ideas being presented.

CONCLUSION

Like sculpture, philosophy and architecture, Greek theatre reflects the culture that created it. The values and intentions of Democratic Athens are clearly outlined in the structure and texts of Greek theatre. The theatre provided a place to learn, trade, socialize, party, release emotions and generally have a great time. The experience of City Dionysia helped to unify and show off the new Democracy in a way that little else could. It is a delight that there is so much of that art form left for modern audiences to enjoy.

THE PLAYWRIGHTS

GREEK TRAGEDY

Sometimes referred to as Attic tragedy, Greek tragedy is an extension of the ancient rites carried out in honor of Dionysus, and it heavily influenced the theatre of ancient Rome and the Renaissance. Tragic plots were often based upon myths from the oral traditions of Archaic epics, and took the form of narratives presented by actors. Tragedies typically began with a prologue, in which one or more characters introduce the plot and explain the background of the story. The

prologue is then followed by paraodos, (an ode sung by the chorus) after which the story unfolds through three or more episodes. The episodes are interspersed by stasima, or choral interludes that explain or comment on the situation that is developing. The tragedy then ends with an exodus, which concludes the story. Each of the playwrights discussed below made contributions to Greek theatrical form and style.

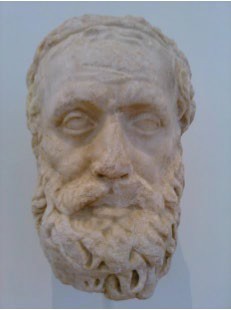

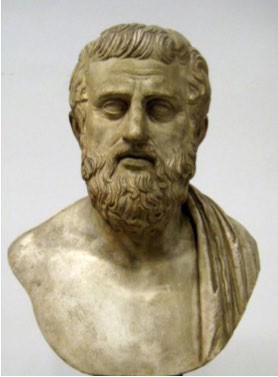

AESCHYLUS AND THE CODIFICATION OF TRAGIC DRAMA

Aeschylus was the first tragedian to codify the basic rules of tragic drama. He is often described as the father of tragedy. He is credited with inventing the trilogy, a series of three tragedies that tell one long story. Trilogies were often performed in sequence over the course of a day, from sunrise to sunset. At the end of the last play, a satyr play was staged to revive the spirits of the public after they had witnessed the heavy events of the tragedy that had preceded it.

According to Aristotle, Aeschylus also expanded the number of actors in theatre to allow for the dramatization of conflict on stage. Previously, it was standard for only one character to be present and interact with the homogeneous chorus, which commented in unison on the dramatic action unfolding on stage. Aeschylus’s works show an evolution and enrichment in dialogue, contrasts, and theatrical effects over time, due to the rich competition that existed among playwrights of this era. Unfortunately, his plays, and those of Sophocles and Euripides, are the only works of classical Greek literature to have survived mostly intact, so there are not many rival texts to examine his works against.

REFORMS OF SOPHOCLES

Sophocles was one such rival who triumphed against the famous and previously unchallenged Aeschylus. Sophocles introduced a third actor to staged tragedies, increased the chorus to 15 members, broke the cycle of trilogies, making possible the production of independent dramas, and introduced the concept of (limited) scenery to theatre. Compared to the works of Aeschylus, choruses in Sophocles’ plays did less explanatory work, shifting the focus to deeper character development and staged conflict. The events that took place were often left unexplained or unjustified, forcing the audience to reflect upon the human condition.

THE REALISM OF EURIPIDES

Euripides differed from Aeschylus and Sophocles in his search for technical experimentation and increased focus on feelings as a mechanism to elaborate the unfolding of tragic events. In Euripides’ tragedies, there are three experimental aspects that reoccur. The first is the transition of the prologue to a monologue performed by an actor informing spectators of a story’s background. The second is the introduction of deus ex machina, or a plot device whereby a seemingly unsolvable problem is suddenly and abruptly resolved by the unexpected intervention of some new event, character, ability, or object. Finally, the use of a chorus was minimized in favor of a monody sung by the characters.

A great way to explore these conventions is to read Euripides’ The Bacchae. The play was written just before the fall of the Democracy, from beyond the borders in Macedonia. Euripides did not live to see it produced in 406 BCE, although his play finally won the prize. In The Bacchae, Euripides, who was a known atheist, questions the cultural values of Athens that brought them to the point of failing power. The playwright consciously manipulates audience expectations as a way of making them view Athens’ rise to power in a different light. All Greek tragedy was based on the agon, or argument. The characters argued, the choruses argued, all in the service of making the audience think. In this, Euripides is no different.

Euripides introduces Tiresius, the blind prophet, the character that traditionally tells the truth. He understands what is happening purely through reason, indicating rationalism. Tiresius is dressed in women’s clothing getting ready to go and dance with the Bacchants or Maenads, female followers of Dionysus. In his agon with the young king Pentheus, he warns the king not to go against the gods. This episode is inappropriately comic, since only women and animals, like satyrs, would act as emotionally as Tiresius does. It points out that pure reason may not be all it is cracked up to be. Euripides goes further by introducing a protagonist, Pentheus. A protagonist carries the theme of the play, and is generally viewed as the hero, but this one, although born noble, is not noble in character. His dependence on pure reason and his idealized view of himself eventually lead to his demise.

Additionally, a god is in the role of the antagonist (the foil that the protagonist struggles against). The fact that Dionysus seems to use more reason than the king is further proof that Euripides does not support the idea that a human can be ideal or that they can succeed when using only reason. He seems to be telling his audience that humans are NOT able to function purely through the use of reason. According to the playwright, they are far too emotional to do so. He, like Socrates, seems to be calling for balance. Each, however, would achieve it in a different way.

Each playwright did indeed contribute new ideas to the development of tragic theatre. With each succeeding generation the plays became more and more like the theatre that is done today. According to Friedrich Nietzsche, in his Birth of Tragedy, Euripides caused the end of the tragic form. In a real sense, he rang the death toll as the purposes of tragic theatre were soon to become obsolete.

THE PHYSICAL STRUCTURE OF THE GREEK THEATRE

The image above shows what the audience member would see at an ancient Greek theatre. The circular space known as the orchestra is in front of the hillside that curves around it. The hillside is filled with stone seating that was added long after the fall of the Athenian Democracy, by the Romans. The Greeks did not use stone seating, other than a few special seats for dignitaries. They sat on the hillside as one would at a picnic. They also had no permanent theater buildings and instead built a temporary wooden stage, the skene, and the building behind it each year, out of wood. Although the structure was not fancy, it served the needs of the Greek Theatre

The Greek theater was a large, open-air structure used for dramatic performance. Theaters often took advantage of hillsides and naturally sloping terrain and, in general, utilized the panoramic landscape as the backdrop to the stage itself. The Greek theater is composed of a few simple areas, the seating area (theatron), a circular space for the chorus to perform (orchestra), and the stage (skene). The slope of a hillside served as the theatron, (which translates to “the seeing place”) providing space for spectators. Two side aisles (parados, pl. paradoi) provided access to the orchestra. The Greek theater inspired the Roman version of the theater directly, although the Romans introduced some modifications to the concept of theater architecture. In many cases the Romans converted pre-existing Greek theaters to conform to their own architectural ideals, as is evident in the Theater of Dionysus on the slopes of the Athenian Acropolis. Since theatrical performances were often linked to sacred festivals, it is not uncommon to find theaters associated directly with sanctuaries.

The Ancient Greek orchestra was round but most today reflect the Roman modification of using a half circle for the area in front of the skene. This is the area in which the chorus danced and sang between sections of dialog (episodes). Scholars argue about whether or not the actors with speaking roles used the orchestra. Most think that it was reserved for the use of the chorus and the aulos, player. The skene, which was raised slightly, was probably where actors would have delivered the dialogue. Keep in mind that this is done in a formal and stylized manner. Greek Theatre was not intended to be realistic like much modern theatre is today.

In the center of the orchestra there was a small altar to Dionysus where the musician played his aulos. Since theatre developed from choral contests, music and dance take up about half of the running time of a play. There was a special type of music reserved for theatrical tragedy. After each section of dialog the chorus sang and danced, often repeating or clarifying important ideas that had just been shared. Although modern readers think of the dialog when looking at ancient theatre, it was the music that playwrights hoped would impress the audience.

In most fifth century theatres the skene was a temporary wooden platform. As time went on and the Classical era passed, many of the skene were built in stone. It was probably on the skene, a raised platform, that both the dialog and the action of the plays took place. Actors wore special shoes that elevated them further. Actors (the two or three that played all of the speaking roles) did not sing or dance. Since the same actor might play several characters, masks helped to identify which character was on the skene at any one time.

The paradoi provided exits and quick entrances for the chorus. There was such an entrance on each side of the orchestra, outside the theatron. Actors, on the other hand, could enter through the temporary building behind the skene or could step up onto the skene from either side. As settings did not change, this was sufficient to control stage traffic. The Theater of Dionysius in Athens (on the lower slope of the Athenian acropolis) was perhaps the most important theatre in the world. People traveled from all over the Greek World to attend, City Dionysia, the five-day Athenian spring theatre festival. The entire city turned itself over to the celebration. In any case all of the tragic plays that are extant (currently in existence), were first performed in this theatre. These hillside theatres allowed large crowds to be able to see and hear the same performance. They also allowed for people to come and go without causing undue interruptions in the action. Song, dance, dialogue and action were accessible to all who attended.

Attributions:

Dr. Jeffrey A. Becker, “Introduction to ancient Greek architecture,” in Smarthistory, August 8, 2015, accessed July 30, 2019.

References:

1. Photo by Syenna Brown. Not available online. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

2. Photo by Giovanni Dall'Orto. [Attribution] https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/5/52/3304_-_Athens_-_Sto%C3%A0_of_Attalus_Museum_- _Theatre_mask_-_Photo_by_Giovanni_Dall%27Orto%2C_Nov_9_2009.jpg

3. Photo courtesy of Kathleen J. Hartman, CC-BY-NC-4.0 License.

4. Photo by Jebulon, CC0, https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/6/6a/Marble_seat_Dionysus_Theatre_Acropolis%2C_Athens% 2C_Greece.jpg

5. Photo by By Alexisrael, CC BY-SA 3.0 license.https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/4/42/Aeschylus_Bust.jpg

6. Photo by Shakko CC BY-SA 3.0 https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/1/19/Sophocles_pushkin.jpg

7. Photo by Vassil, CC0 https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/b/b6/British_Museum_Room_20a_Oenochoe_Dutuit_Painter_Sat yr_and_maenad_Detail_19022019_6662.jpg

8. Ancient Greek theatre at Delphi. Zde [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)] https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/6/60/Ancient_Greek_theatre_at_Delphi%2C_Dlf474.jpg

9. Photo by Jorge Láscar from Australia, CC BY 2.0, https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/4/40/ Lascar_Theatre_of_ Dionysus_ %284517133411%29.jpg

10. Photo by Antonio Salinas, CC BY 2.5 https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/7/72/Aulos_player_MAR_Palermo_NI22711.jpg

11. Photo by George E. Koronaios, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/1/1e/At_the_Great_Theatre_of_Epidaurus.jpg