4.9 From the Archaic to the Classical Period

The Archaic Period (800-480 BCE) is characterized by the introduction of republics instead of monarchies organized as single city-states or polises. In Athens, they moved toward democratic rule. Laws such as Draco’s reforms in Athens were created. The great Panathenaic Festival was established in Athens. The Panathenaic Festival was a once a year festival honoring Athena and involving the entire City of Athens. This was the most important religious festival in Athens and it involved several types of contest, including races, poetry, equestrian events and other sports contests involving men and boys. There was a great procession and ritual that young girls proudly took part in. Distinctive Greek pottery and Greek sculpture were refined, and the first coins were minted on the island kingdom of Aegina. This was a time of innovation and change, investigation, development and domination.

These changes set the stage for the flourishing of the Classical Period of ancient Greece. Athens lost its Democracy in 404 BCE, ending the high Classical period. However, the ideas generated during that time continued to influence the known world and Greece continued to be a moving force in that world until the death of Alexander in 323 BCE. From the Greek victory at the Battle of Salamis in 480 BCE, to the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BCE the western world fell under the influence of the Greeks.

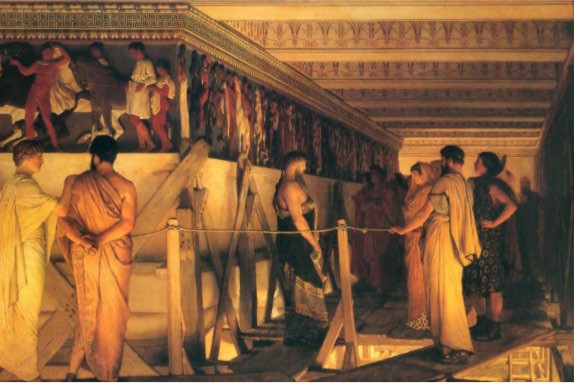

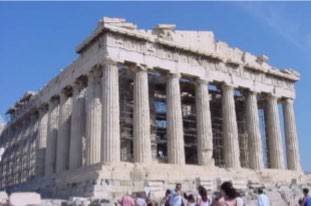

During the Golden Age of Athens, from 480 BCE until the fall of the Democracy in 404 when Pericles initiated the building of the Acropolis and just before the period began, he spoke his famous eulogy for the men who died defending Greece at the Battle of Marathon in 490 BCE. Pericles was the most famous Athenian statesman. He was elected General and led Athens to its height. He then witnessed the beginning of its destruction. It was Pericles who helped to form the Athenian League and who supervised the building of the Parthenon, a Temple to Athena which was built on the Athenian acropolis. Most cities in Greece had a defendable hill in the middle of the city where their important buildings were located.

Greece reached heights in almost every area of human learning during this time and the great thinkers and artists of antiquity such as Phidias, Plato, and Aristophanes, flourished and shared ideas in Athens. Leonidas and his 300 Spartans fell at Thermopylae and, the same year (480 BCE), Themistocles won victory over the superior Persian naval fleet at Salamis leading to the final defeat of the Persians at the Battle of Plataea in 479 BCE.

GREECE REACHED THE HEIGHTS IN ALMOST EVERY AREA OF HUMAN LEARNING DURING THE CLASSICAL PERIOD

Democracy which when translated literally refers to Demos = people and Kratos = power, so power of the people, was established in Athens allowing all male citizens over the age of twenty a voice in the Greek government. The Pre-Socratic philosophers, following Thales’ lead, initiated what would become the scientific method in exploring natural phenomena. Men like Anaximander, Anaximenes, Pythagoras, Democritus, Xenophanes, and Heraclitus abandoned the theistic model of the universe and strove to uncover the underlying, first cause of life and the universe.

Euclid and Archimedes continued to advance Greek science and philosophical inquiry and further established mathematics as a serious discipline. The example of Socrates and the writings of Plato and Aristotle have influenced western culture and society for over two thousand years. The Golden Period also saw advances in architecture and art with a movement away from the symbolic to the naturalistic ideal. Famous works of Greek sculpture such as the Parthenon Marbles and Discobolos known as the discus thrower, date from this time and epitomize the artist’s interest in depicting human reason, beauty, and accomplishment naturally, even if those qualities are presented in works featuring immortals.

All of these developments in culture were made possible by the ascent of Athens following the victory over the Persians in 479 BCE. The peace and prosperity that followed the Persian defeat provided the finances and stability for culture to flourish. Athens became the superpower of the day and, with the most powerful navy, was able to demand tribute from other city-states and enforce its wishes. Athens formed the Delian League, a defensive alliance whose stated purpose was to deter the Persians from further hostilities. The Athenians became so powerful that they considered themselves to be forming an Empire. Pericles set out to make Athens the jewel of the world in terms of knowledge, learning, the arts and philosophy. The powerful Athenian government, based on the Democracy was considered by many to be the reason that Athens was able to have such a large part in defeating Persia. After all, who would make the better army, Persian slaves who had little power over their own lives and as such limited allegiance to their masters, or the brave Athenians who fought for their homes, families and freedom?

With great pride Athens drew into her midst the greatest minds of the age. Pythagoras developed his geometry and a system for writing down music and for reliably duplicating it. The great philosophers, Socrates and Plato would continue to develop secular philosophy, driving it in an entirely new direction. Theatre would develop into a popular entertainment as well as supporting the Classical ideas that birthed it. Greek architecture reached its pinnacle in temples dedicated to the gods and in the Parthenon, dedicated to Athenian Democracy. These ideas, like the popular red figure pottery of Athens, would spread across the known world, changing it forever.

THE DELIAN LEAGUE

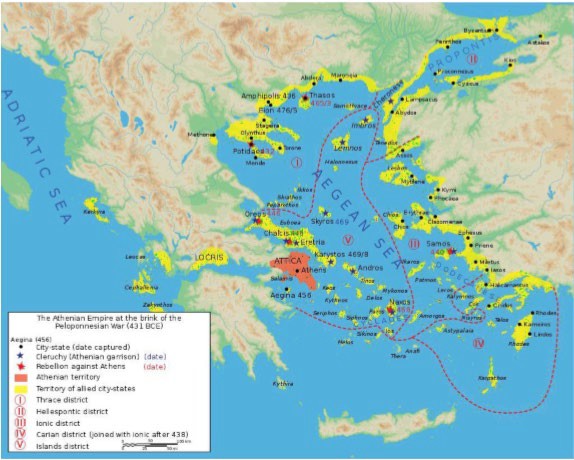

The Delian League (or Athenian League) was an alliance of Greek city-states led by Athens and formed in 478 BCE to liberate eastern Greek cities from Persian rule and as a defense to possible revenge attacks from Persia following the Greek victories at Marathon, Salamis, and Plataea in the early 5th century BCE. The alliance of over 300 cities would eventually be so dominated by Athens that, in effect, it evolved into what some scholars refer to as, the Athenian empire, although it was never ruled by an Emperor. Athens became increasingly more aggressive in its control of the alliance and, on occasion, constrained membership by military force and compelled continued tribute that was in the form of money, ships or materials. Following Athens’ defeat at the hands of Sparta in the Peloponnesian War in 404 BCE the League was dissolved. This alliance was, however, a large part of what allowed Athens to rise to the position of the most influential city in the ancient world.

Membership & Tribute

The name, Delian League is a modern one; the ancient sources refer to it as simply ‘the alliance’ (symmachia) or ‘Athens and its allies’. The name is appropriate because the treasury of the alliance was located on the sacred island of Delos in the Cyclades. The number of members of the League changed over time but around 330 BCE they are recorded in tribute lists; sources which are known to be incomplete. The majority of states were from Ionia and the islands but most parts of Greece were represented and later there were even some non-Greek members such as the Carian city-states.

Prominent members included: Aegina, Byzantium, Chios, Lesbos, Lindos, Naxos, Paros, Samos, Thasos and many other cities across the Aegean. Members were expected to give tribute to the Delian Treasury, which was used to build and maintain the Naval Fleet controlled by Athens.

Initially members swore to hold the same enemies and allies by taking an oath. It is likely that each city-state had an equal vote in meetings held on Delos. Members were expected to give tribute (phoros) to the treasury, which was used to build and maintain the naval fleet led by Athens. Significantly, Athenian treasurers controlled the treasury. The tribute in the early stages was 460 talents (raised in 425 BCE to 1,500), a figure decided by Athenian statesman and General Aristides. An alternative to providing money was to give ships and/or materials such as timber and grain.

The Delian League enjoyed some notable military victories such as at Eion, the Thracian Chersonese, and most famously, at the Battle of Eurymedon in 466 BCE, all against Persian forces. As a consequence Persian garrisons were removed from Thrace and Chersonesus. In 450 BCE the League seemed to have achieved its aim if the Peace of Kallias is to be considered genuine. Here the Persians were limited in their field of influence and direct hostilities ended between Greece and Persia.

Other successes of the League were not military but economic and political, making them more difficult to determine in their significance and real effect for all members. Piracy was practically eliminated in the Aegean, inter-city trade increased, a common coinage was introduced (the Athenian silver tetradrachm), taxation became centralized, democracy as a form of government was promoted, the judiciary of Athens was accessible to member’s citizens, and such tools as measurement standards became uniform across the Aegean.

The primary beneficiary of all of these was certainly Athens and the massive re-building project of the city, begun by Pericles and which included the Parthenon, was partially funded by the League treasury. In fact, much to the dismay and frustration of some allies, Pericles moved what was left of the Delian Treasury to the new Athenian Parthenon.

CLASSICAL ARCHITECTURE AND THE PARTHENON: AN OVERVIEW

Classical Greek Architecture: The Doric Order

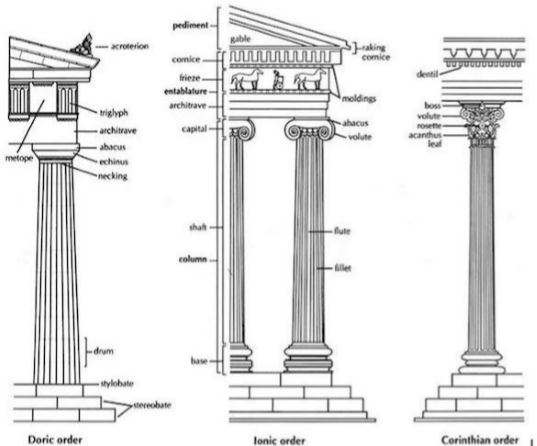

An architectural order describes a style of building. In classical architecture each order is readily identifiable by means of its proportions and profiles, as well as by various aesthetic details. The style of column employed serves as a useful index of the style itself, so identifying the order of the column will then, in turn, situate the order employed in the structure as a whole. The classical orders—described by the labels Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian—do not merely serve as descriptors for the remains of ancient buildings, but as an index to the architectural and aesthetic development of Greek architecture itself. In order to best understand the structure and politics of the Parthenon, it is important to review the Doric style as well as the newer, lighter ionic style. Perhaps as a way to placate allies who were angry over the move of the League funds from Delos to Athens, the Parthenon, which would now house the money, was built in both the Doric (earlier southern style) and the Ionic (associated with Athens) styles.

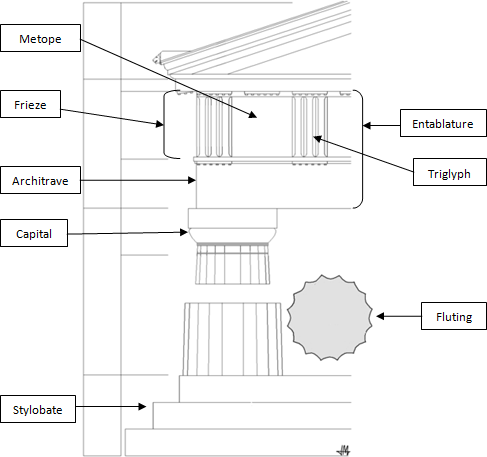

The Doric order is the earliest of the three Classical orders of architecture and represents an important moment in Mediterranean architecture when monumental construction made the transition from impermanent materials such as wood to permanent materials like stone. The Doric order is characterized by a plain, unadorned column capital and a column that rests directly on the stylobate of the temple without a base. The Doric entablature includes a frieze composed of trigylphs (vertical plaques with three divisions) and metopes (square spaces for either painted and/or sculpted decoration). The columns are fluted and are of sturdy, if not stocky, proportions. The 1/8 proportions of the Doric temple are seen in the width of the column drum being 1/8 the height of the column.

Each column on the exterior swells slightly and is narrowest at the top. This is referred to as entasis and it is seen in most Doric temple columns. It creates a lively feel and is almost as though many arms with strong flexing muscles hold up the building. Although Doric temples are large, they are clearly designed primarily for human use and as such, are more human-sized than ancient temples in most other cultures.

Compare Egypt’s Temple of Hatshepsut, which is larger than The Parthenon. In the right front view of the Athenian Parthenon, the roof is no longer there. The pediment and metopes are badly damaged and mostly missing. A row of the interior ionic columns stands behind the Doric exterior columns. This is representative of the mix of styles that was possibly an attempt to appeal to Athenian allies whose funds were used to construct the building.

Notice that both the Egyptian temple and the Greek Parthenon were built using post and lintel construction, although a pediment has been added to the Parthenon. Each has capitals, fluting and a portico. The Egyptian columns are of a single piece of granite that is taller than the Parthenon columns. The Greeks created columns by assembling sections called drums. Lastly, the three-tiered funeral temple of Hatshepsut reaches 97 feet in height, while the tallest point on the Parthenon is 64 feet in height.

The Doric order emerged on the Greek mainland during the course of the late seventh century BCE and remained the predominant order for Greek temple construction through the early fifth century BCE, although notable buildings of the Classical period, especially the canonical Parthenon in Athens, still employ it. By 575 BCE. the order may be properly identified, with some of the earliest surviving elements being the metope plaques from the Temple of Apollo at Thermon. The Doric order finds perhaps its fullest expression in the exterior of the Athenian Parthenon designed by Iktinos and Kallikrates in about 447-432 BCE.

Classical Greek Architecture: The Ionic Order

Image 4.78 presents an ionic capital that sits at the top of the column, and that held up the pediment above it. Between the pediment and the column there was an unbroken frieze, which did not include triglyphs. The ionic capital has a scroll-like design known as a volute, at each corner. There was decorative carving in a band beneath the volutes and above the fluting that fills the rest of the column. Although it is not visible in this image, the column originally sat on a base, unlike the Doric columns. The 1/9 proportions of the Ionic temple can be seen in the column width being 1/9 of the column height. Watch for the return of this proportion during the Gothic age. As its name suggests, the Ionic Order originated in Ionia, a coastal region of central Anatolia, which is now Turkey, where a number of ancient Greek settlements were located. The Ionic order developed in Ionia during the mid-sixth century BCE and had been transmitted to mainland Greece by the fifth century BCE.

The monumental temple dedicated to Hera on the island of Samos and built by the architect Rhoikos c. 570-560 BCE, was the first of the great Ionic buildings, although it was destroyed by earthquake in the sixth century BCE. The Temple of Artemis at Ephesus, a wonder of the ancient world, was also an Ionic design. In Athens the Ionic order influenced some elements of the Parthenon, notably the Ionic frieze that encircles the cella, a room within the temple that normally held a statue of the patron god or goddess. Ionic columns are also employed in the interior of the monumental gateway to the Acropolis known as the Propylaia built circa 437-432 BCE. The Ionic style was promoted to an exterior order in the construction of the Erechtheum built circa 421-405 BCE and the temple of Athena Nike, on the Athenian Acropolis.

Notice that the slender ionic columns taper as they rise to meet the architrave that is just below what is left of the frieze. The Ionic order is notable for its graceful proportions, creating a more slender and elegant profile than the Doric order. The ancient Roman architect, Vitruvius, compared the Doric building to a sturdy, male body, while the Ionic was possessed of more graceful, feminine proportions. The Ionic order incorporates a running frieze of continuous sculptural relief, as opposed to the Doric frieze, composed of triglyphs and metopes.

Classical Greek Architecture: The Corinthian Order

The final Classical style, the Corinthian, was used in interiors of buildings but is not seen in the Parthenon. However, it is included here as it has a considerable influence on later Roman architecture. The Corinthian order is both the most recent and the most elaborate of the Classical orders of architecture. The order was employed in both Greek and Roman architecture, with minor variations, and gave rise in turn to the Composite order. As the name suggests, the origins of the order were connected in antiquity with the Greek city-state of Corinth where, according to the architectural writer Vitruvius, the sculptor Callimachus drew a set of acanthus leaves surrounding a votive basket. The Corinthian style is in a 1/10 proportion and as such is taller and leaner than the Ionic and Doric styles. In archaeological terms the earliest known Corinthian capital comes from the Temple of Apollo Epicurius at Bassae and dates to c. 427 BCE.

The defining element of the Corinthian order is its elaborate, carved capital, which incorporates even more vegetal elements than the Ionic order. The stylized, carved leaves of an acanthus plant grow around the capital, generally terminating just above a band that separates the capital from the column. The Romans favored the Corinthian order, perhaps due to its slender properties. The order is employed in numerous Roman architectural monuments, including the Pantheon in Rome and this example, from Jerash, Jordan where Roman settlers brought their architectural influences.

Attributions:

Mark, Joshua J. “Ancient Greece.” Ancient History Encyclopedia. Ancient History Encyclopedia, 13 Nov 2013. Web. 01 Dec 2019. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

Cartwright, Mark. “Delian League.” Ancient History Encyclopedia. Ancient History Encyclopedia, 04 Mar 2016. Web. 01 Dec 2019. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

References:

1. Public domain, https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/3/3e/1868_Lawrence_Alma-Tadema_-

_Phidias_Showing_the_Frieze_of_the_Parthenon_to_his_Friends.jpg

2. By Marsyas uploaded by Mark Cartwright CC BY-SA.https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Delian_League #/media/File:Map_athenian_empire_431_BC-en.svg

3. Photo by Rob Sing, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 https://search.creativecommons.org/photos/799d8ca9-72d6-4093-8ade-c77fffb0d161

4. Dr. Jeffrey A. Becker, “Greek architectural orders,” in Smarthistory, August 8, 2015, accessed December 26, 2019, https://smarthistory.org/greek-architectural-orders/.

5. Image based on a work by Amadalvarez, edited by Kristine Betts, CC0 License https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Layout_doric.gif

6. Photo by izzie_whizzie is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0 https://search.creativecommons.org/photos/1d7d6ac6-a61d-423a-8c26-fd95f3478310

7. Photo by atheism is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2. https://search.creativecommons.org/photos/6f9884ca-30d0-4064-ad42-69d8863a37c3

8. Photo by profzucker is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 https://search.creativecommons.org/photos/349a491f-6325-4855-a567- e8a6d167ecae

9. Photo by Aleksandr Zykov is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0 https://search.creativecommons.org/photos/9951ff9b-54a3-4a91-860b- a26c93501b9b

10. Photo by Michael Bunther, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Jerash,_Corinthian_Column._Jordan0928.jpg