4.14 FROM POWER TO COLLAPSE, OR

FROM THE CLASSICAL TO THE LATE CLASSICAL PERIOD

When Athens formed the Delian League and began to take over the running of it, the city-state of Sparta doubted Athenian sincerity and formed their own association for protection against their enemies. It was called the Peloponnesian League , so named for the Peloponnese region where Sparta and the others were located. The city- states which sided with Sparta increasingly perceived Athens as a bully and a tyrant, while those cities which sided with Athens viewed Sparta and its allies with growing distrust. This would be the beginning of the end for the Democracy.

Already looking like it was corrupted by Athenian ambition; two further episodes changed the League forever. In 460 BCE the First Peloponnesian War broke out between Athens, Corinth, Sparta, and their allies. For the first time the League was being used against Greek city-states and Persia was off the agenda. Then c. 454 BCE Athens used the excuse of a failed League expedition in Egypt, which was to aid the anti-Persian prince Inarus, to move the League treasury to Athens.

The League became, thenceforth, even more difficult to control. In 446 BCE Athens lost the Battle of Koroneia and had to repress a major revolt in Euboea. An even more serious episode occurred when fighting between Samos and Miletos, both League members, was escalated by Athens into a war. Again the Athenians’ superior resources brought them victory in 439 BCE. Yet another revolt broke out in Poteidaia in 432 BCE that brought Athens and the Delian League in direct opposition with Sparta’s own alliance, the Peloponnesian League.

This second and much more damaging Peloponnesian War (432-404 BCE) against a Persian-backed Sparta would eventually, after 30 years of grueling and resource-draining conflicts, bring Athens to her knees and ring the death knell for the Delian League. Such disastrous defeats as the 415 BCE Sicilian Expedition and the brutal execution of all males on rebellious Melos the previous year were indicators of the desperate times. Athens’ glory days were gone and with them, the Delian League. By 404 BCE Athenian Democracy was ended.

This time is generally referred to as the Late Classical Period (c. 400-330 BCE). Philip II of Macedon (382-336 BCE) filled the power vacuum left by the fall of these two cities, after his victory over the Athenian forces and their allies at the Battle of Chaeronea in 338 BCE. Philip united the Greek city-states under Macedonian rule and, upon his assassination in 336 BCE, his son Alexander assumed the throne.

The art of the late Classical period began to change with the political changes. The Greek ideal was no longer attainable. With no democracy in place, individuals no longer had any power over the government under which they lived and labored. Instead Athenians and other Greeks turned their attention to themselves and their families, ushering in an era of individualism. The ideal of Athens became tarnished and a more realistic view of the world took its place. Much of the idealism that remained would transform into propaganda for Alexander the Great and those who would follow him. A new aesthetic began to form and it can be seen in the late Classical period.

The benefits of the League had been mostly for the Athenians, nevertheless, after 404 BCE it is significant that the realistic alternative , Spartan rule, would not have been any more popular for the lesser states of Greece. This is perhaps indicated by their willingness to re-join with, albeit a weaker and more militarily passive, Athens in the Second Athenian Confederacy from 377 BCE. Once Democracy was disbanded in 404 BCE, Athens would never again rule the Aegean Sea or lead the world in the arts and learning.

Although image 4.137 was made in response to those lost in the War against Persia, it seems fitting to place her here, where she can mourn the fall of a once great city that bears her name.

THE LATE CLASSICAL: GREEK SCULPTURE MOVES IN A NEW DIRECTION

After the fall of the Democracy, the image of a marshal warrior, free and independent, no longer had the same appeal. Under the Oligarchy and later the Monarchy of Phillip 2nd and then that of his son, Alexander the Great, this image of the ideal man no longer had a place. People could no longer impact their own political life. Focus turned to more personal and achievable goals. As might be expected, this transition period was accompanied by a transition in art and with the ideas of Aristotle in philosophy and even theatre.

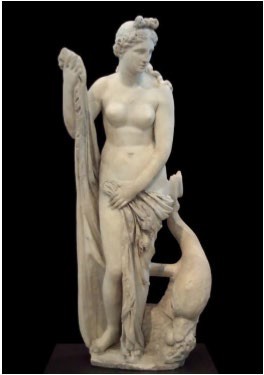

One of the first sculptors to embrace the new focus was named, Praxiteles. He was, as far as is known, the first sculptor to become so well known and loved that he could create art without first having a sponsor to commission it. This may have begun with his most famous sculpture, Aphrodite of Knidos. He made two copies for his commission, one clothed, and another, boldly naked. Click the link below and view the video about how this bold change began.

If you have trouble viewing the video above, use this link: https://smarthistory.org/capitoline-venus-copy-of-the-aphrodite-of-knidos/.

Notice that this copy has been modified to better fit Roman tastes. In the first century CE, the new Emperor, Augustus, traced his lineage to Aphrodite (This was part of a campaign during which Virgil was commissioned to write a new epic about Rome’s beginnings in Troy, called The Aeneid) so viewers are treated with the dolphin associated with the sea, where the Goddess of love came into being. Her hair seems to also be updated to fit the tastes of the viewers of that time. In nearly every other way, this copy of Aphrodite, later called Venus, resembles her predecessors. Like most art of this time the subject is caught in the moment she steps from her bath, rather than depicting potential.

The idea of art being created without a sponsor lined up ahead of time points to a new attitude. As the Athenian Democracy and many of the former Republics were no longer commissioning large art projects, it fell to individuals to continue the tradition. As the political landscape changed so did the economic one. Praxiteles was able to sell both of his statues. The type of loyalty formerly associated with sculptors like Phidias, who carved for Greeks, whether they were from the north or the south, was shifting. His work is known from its importance to the Greek mainland. Now loyalty was to whoever could best pay for work and Phidias did not work for free. But in this new age, Praxiteles began a new approach to selling his wares; he used speculation and made his work before he had a buyer.

A more subtle change than the added prop or the somewhat exotic nature of Aphrodite of Knidos is the fact that when carving in marble, Praxiteles evidently chose a marble with a slightly pink tint, because it was closest to natural skin tone. He still had his sculptures painted, although probably not the skin itself. The painting was important enough that scholars today know the name of his painter, Nicias. Such focus on the artist was not entirely new but it certainly increased as speculation became more prominent.

Another famous statue that has been attributed to Praxiteles is Hermes and Dionysus. This sculpture demonstrates a graceful elegance, rather than the strength and bravery of High Classical art. Grace and elegance, like the eroticism of Aphrodite of Kindos is more of a personal trait than a public one and unlike the strength of the marshal warrior, it serves the individual, rather than the state.

Notice that the Late Classical statue of Hermes is closer to a 1/8 proportion in comparison to the 1/7 proportions of the High Classical, Doryphorus. The introduction of these proportions is generally credited to one of Praxiteles’ contemporaries, the sculptor, Lyssipus. While the warrior holds only a spear, Hermes leans on a prop, apparently cloth draped over something. He also holds a baby, something not seen in any existing High Classical sculpture. This nod to domesticity makes sense in a world where it was becoming increasingly difficult to impact anything outside one’s family. The infant seems to share the proportions of Praxiteles’ tall adult as his head is not the same in proportion to his body as the head of a real infant is.

Praxiteles also focuses on texture. In most of the statues attributed to him there are highly polished areas that contrast with rougher textures. Perhaps the well-known sculptor was showing off his skills in order to continue to raise his reputation and thereby sell his work. The body of Hermes is still flawless and his expression is calm. In many ways he still exhibits elements expected of the Classical era but in other ways, he breaks away from tradition. Note, for instance, that the sculptor incorporates contrapposto but it is much more exaggerated that the stance of Doryphorus. Including a child introduces an emotional subject, not something seen earlier in the Classical period.

When thinking of a canon for the Late Classical era, this sculpture is a good choice, since many sculptors copied the style in the following years.

For a closer look at the change in proportions that helps to define the Late Classical sculpture style, view this video on the sculpture, Apoxyomenos, by the sculptor, Lyssipus.

APOXYOMENOS(SCRAPER).6 (4:16)

If you have difficulty viewing the video above, use this link: https://smarthistory.org/lysippos-apoxyomenos-scraper/

Lyssipus worked in bronze. The stump was probably added as support for the marble copy. This is not the only statue with this name but it is certainly the most famous.

Above are images of another Roman copy of a sculpture by Lyssipus. The Farnese Hercules is also a Roman copy of a sculpture by Lyssipus. It is named for the Roman family that found it and employs the new, taller canon of proportions and the exaggerated contrapposto pose. In addition, there are apples in the hand that Hercules (Roman spelling) holds behind his back. This colossal statue (10 ½ feet tall) provides a reason to walk around it in order to view the entire thing. Notice that he appears exhausted, something never seen in High Classical sculpture, because it would not have been ideal. During the Late Classical period emotion begins to creep into what was formerly calm repose.

The art of the Late Classic period is a transition style that begins to incorporate the ideas of Aristotle, Plato’s student. Plato considered knowledge to be the highest good and Rationalism, Humanism and Idealism were the values that he and his teacher, Socrates, embraced. Aristotle eventually had to begin his own school, as Plato would not allow him to teach in the Platonic academy. Aristotle believed that happiness was the highest good and he embraced Empiricism, reflected in art as Realism. He also embraced individualism. The seeds of these ideas can be perceived in Late Classical sculpture in its attention to a new kind of beauty, based on elegance, the exaggeration of movement, which would increase during the Hellenistic age and in the attention to the experience of the moment, rather than on potential.

These ideas would continue to develop alongside Plato’s ideas, and with them would be spread across the known world by Alexander the Great. The diversity of values that the competing ideas represent, make the Hellenistic era an exciting and challenging period to study. A careful look at Late Classical art provides hints of what was to follow the Classical era and of what would define the Hellenistic period.

Attributions:

Cartwright, Mark. “Delian League.” Ancient History Encyclopedia. Ancient History Encyclopedia, 04 Mar 2016. Web. 01 Dec 2019. Modified for “From Power to Collapse.” By T. Kate Pagel, PhD. Humanities: New Meaning From the Ancient World. Colorado Springs, CO: Pikes Peak Community College, 2019. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

References:

1. Harrieta171 assumed (based on copyright claims), CC BY-SA 3.0 https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/ File:Acropole_ Musée_ Athéna_ pensante.JPG

2. Photo by Shawn Lipowski (Shawnlipowski), CC BY-SA 3.0 https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/b/bc/Roman_Venus_Copyof_Praxiteles_Front.jpg

3. Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris, “Capitoline Venus (copy of the Aphrodite of Knidos),” in Smarthistory, April 5, 2016, accessed January 1, 2020, https://smarthistory.org/capitoline-venus-copy-of-the-aphrodite-of-knidos/ .

4. Photo by tetraktys, CC BY-SA 2.5. Archaeological Museum , Olympia, Greece. Parian marble 7’1”, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki /File: Hermes_di_Prassitele,_at_Olimpia,_front_2.jpg.

5. Photo by Kathleen J. Hartman, CC BY-NC- 4.0 License.

6. Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker, “Lysippos, accessed January 1, 2020, Apoxyomenos (Scraper) ,” in Smarthistory https://smarthistory.org/lysippos-apoxyomenos-scraper/

7. Photo by Yair Haklai, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Apoxyomenos-the_Scraper-Pio-Clementino-2.jpg

8. Photo by Miguel Hermoso Cuesta, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hércules_Farnese.JPG

9. Photo by xinstalker, CC BY 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Eracle_Farnese_(detail).jpg