3.1 Egypt – Introduction and Predynastic Years

Ancient Egypt serves as an excellent example of a complex society which adapted to and then controlled their changing environments. Cross-cultural connections introduced the people of Northeast Africa to domesticated wheat and barley.

People in part of the world had likely been gathering wild barley since before 10,000 BCE. However, by about 7,000 BCE they had learned from the people in the Fertile Crescent and began cultivating wheat and barley and also kept domesticated animals, including sheep and goats. At that time, agricultural production and herding were possible in areas that are today part of the Sahara Desert because it was much wetter than it is now. However, environmental change was leading to the desiccation or drying out of areas not adjacent to the Nile River, and by about 5,000 BCE, it was no longer possible to farm much beyond the floodplain of the Nile River. Many people adapted by moving towards the Nile River, and the Nile became increasingly important to Egypt’s populations.

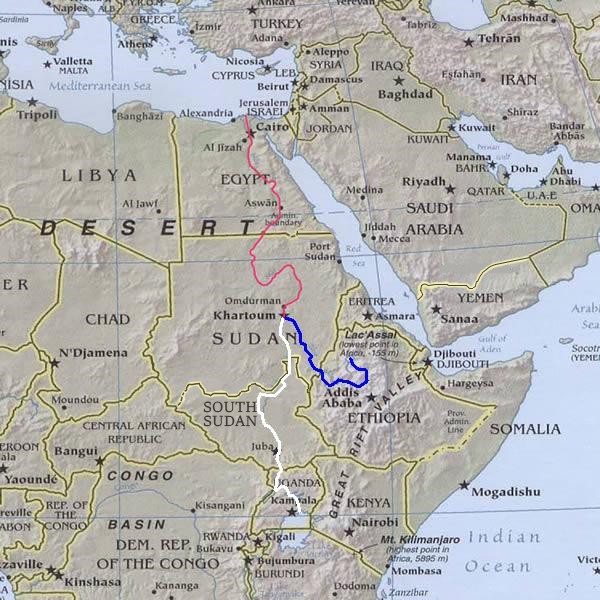

The Nile River flows south to north, fed by two main river systems: the White Nile and the Blue Nile. The White Nile flows steadily throughout the year and has its origins in the Great Lakes Region of East Africa. The Blue Nile originates in the Ethiopian highlands, and brings floodwaters up past the first cataract in the summers.

Cataracts are generally considered impassable by boat due to their shallows, rocks, and rapids. The winds also blow north to south, in the opposite direction of the river flow, thus making it difficult to trade and maintain contact between Upper Egypt (to the south) and Lower Egypt (to the north). Egyptian views of the Nile generally recognized the river’s centrality to life as demonstrated in the “Hymn to the Nile,” dated to approximately 2100 BCE.

The praise-filled ode to the Nile River begins, “Hail to thee, O Nile! Who manifests thyself over this land, and comes to give life to Egypt.”2 The course of the Nile River definitely impacted settlement patterns, while the river also allowed for trade and the development of larger agricultural communities.

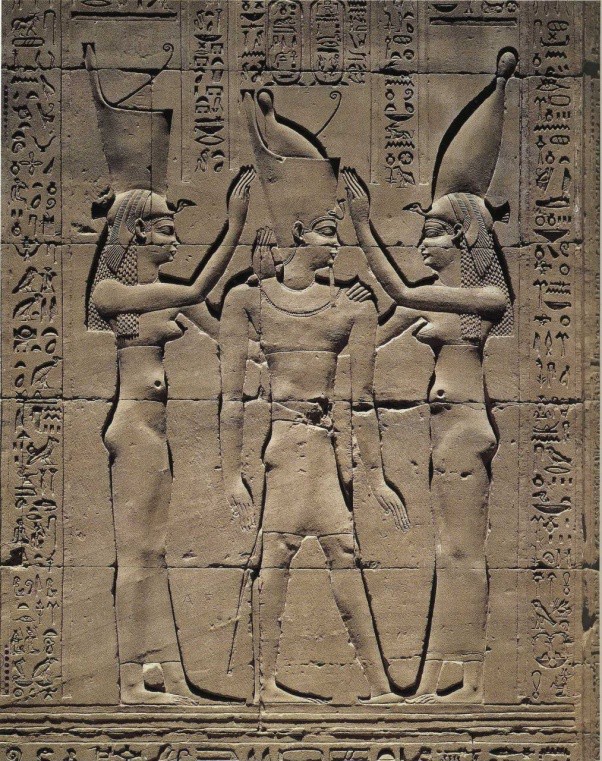

The Nile Goddess, Hapi, as seen in image 3.2, bears a tray of lotus blossoms and water vessels. Two ankh (life) and djed (stability) hang from the tray. This image is from the reign of Nectaneba II, in 362-343 BCE. Each year the Nile flooded, leaving behind rich alluvial soil which nourished the land along the banks and allowed the people to plant and harvest several cycles of crops. Taxation was determined by the height of the flooding river. In years when the flood was minimal, there might be starvation, but at least the taxes might be lower. At the edge of the newly deposited river soil the desert and its unrelenting heat took over. The Greek philosopher and traveler Herodotus said Egypt was a gift of the Nile because Egypt relied so heavily on it.5 The White Nile originates near Lake Victoria, in the Great Lakes region of East Africa. The Blue Nile flows from the Ethiopian Highlands. The two rivers merge at Khartoum, in present day Sudan, and flow northward to empty into the Mediterranean Sea.

Over time, Egyptian rulers created divine kingships, asserting their right to even more power and access to resources, power that they legitimized by claiming special relationships with, or even descent from the gods. Once Egypt was unified, pharaohs ruled as divine kings, as the personification of the gods and they promised order in the universe. When things went well, the pharaohs were credited with agricultural productivity and the success of the state. There was no separation between religion and the state in ancient Egypt. Keep in mind that modern historians call these kings pharaohs, though they were not known as pharaohs in their own time until about 1200 BCE. For simplicity we will call them pharaohs in this text.

The Palette of Narmer, see image 3.5, can be used to date the unification of Egypt. It was a ceremonial palette that might have been used to hold makeup. It shows signs that King Narmer legitimized his rule, in part, by claiming a special relationship with the gods. King Narmer, who is referred to in some texts by his Greek name Menes, is commonly recognized as the first unifier of Upper Egypt (to the south) and Lower Egypt (to the north) in approximately 3100 BCE. Unification brought together Egypt from the first cataract at Aswan to the Nile Delta. The Palette of Narmer, which was found in Hierakonpolis, shows King Narmer’s conquest of both regions. One side shows him slaying an enemy of Upper Egypt. The largest figure, Narmer is wearing the crown of Upper Egypt and beheading a rival king, while standing atop conquered enemies. The other side also shows him as a conqueror, wearing the crown of Lower Egypt and directing flag bearers to mark his victory. When Narmer unified Upper and Lower Egypt, he took the two crowns and put them together into what we call the Peshret Crown or Double Diadem crown, to symbolize that he now rules all of Egypt. See image 3.6 for an example of this.

Religious imagery appears in the inclusion of the goddess Hathor at the top of the palette as well as the falcon, a reference to Horus, the patron god of Hierakonpolis, who became the god of sun and kingship later in dynastic Egypt. The Palette of Narmer is an excellent example of the fact that Egyptian sculpture followed a specific set of rules.

- Space is flattened. The artist uses “bird’s eye” perspective, which allows the viewer to see all aspects of an image at the same time. Note two examples of this in the lower register which shows a bull with a profile head and frontal horns. The artist also carved the city looking across to its ramparts and also shows a view from above looking down at the walls surrounding it.

- Objects are manipulated to fit into the available space.

- The surface of the work, whether it is the wall of a temple, a column, or the side of an object, is divided into sections to tell a story.

- People and gods and animals are shown with their legs and feet in profile, their torsos facing the viewer, and their heads in profile. Eyes are large and frontal.

- The pharaoh is divine and he (or she) is often shown consorting with the gods or enjoying their protection.

- The most important person is the largest. We call this hierarchical scaling, which depicts the figure of the king, in this case Narmer, as much larger than the enemy he is about to dispatch.

- A pharaoh can only be depicted sitting, kneeling, or standing. Other positions are not appropriate.

- Most humans are depicted ideally rather than realistically.

The Palette of Narmer also has some of the earliest known hieroglyphs or written text, combines pictograms (a pictorial symbol for a word or phrase) and phonograms (a symbol representing a sound). Tax assessment and collection likely necessitated the initial development of Hieroglyphics. Ancient Egyptians eventually used three different scripts: Hieroglyphic, Hieratic, and Demotic. Hieroglyphics remained the script of choice for ritual texts. The Egyptians developed Hieratic and Demotic, the two other scripts slightly later and used them for administrative, commercial, and other purposes. The Egyptian administration tended to use ink and papyrus to maintain its official records.

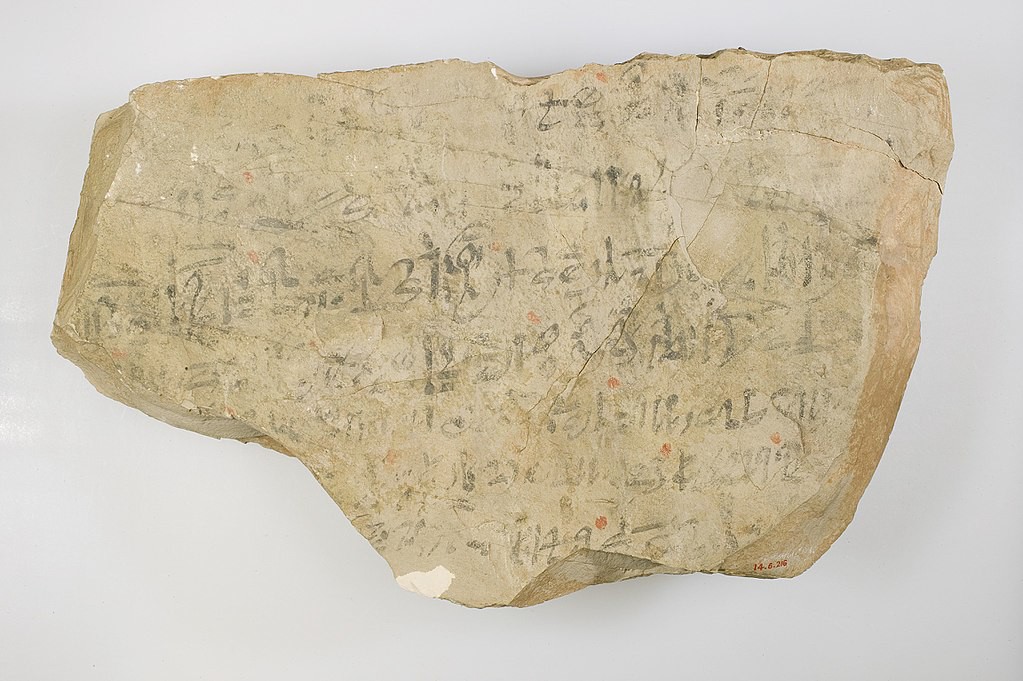

On the other hand, literate people used ostraca, pieces of broken pottery and chips of limestone, for less formal notes and communications. Over the past decades, archaeologists have uncovered a treasure trove of ostraca that tell us about the lives of the literate elite and skilled craftsmen. This one is from Thebes in the Valley of the Kings. See image 3.7.

In addition to one of the earliest writing systems and Egyptian paper (papyrus), archaeologists have credited ancient Egyptians with a number of other innovations. We remember them for their process of mummification, pharaohs, pyramids, and stone carving techniques. Ancient Egyptians invented the ramp and lever. They also developed a 12-month calendar with 365 days, glassmaking skills, arithmetic (including one of the earliest decimal systems), geometry, and medical procedures used to heal broken bones and relieve fevers.

Scholars break the 1500 years following unification, a time known as dynastic Egypt, into three main periods: the Old Kingdom (c. 2660–2160 BCE), the Middle Kingdom (c. 2040 – 1640 BCE), and the New Kingdom (c. 1530–1070 BCE). There is disagreement about the exact dates of these periods, but, in general, these spans denote more centralized control over a unified Egypt. If you search the Internet, you will encounter many different dating systems for Egyptian history. During dynastic Egypt, pharaohs ruled a united Upper and Lower Egypt. In between these periods of centralized control were intermediate periods, during which the Egyptian pharaohs had less authority. The intermediate periods were characterized by political upheaval and military violence, sometimes resulting from foreign invasions.

Striking continuities existed in Egypt throughout the Old Kingdom, the Middle Kingdom, and the New Kingdom. Egypt had stable population numbers, consistent social stratification, pharaohs—who exercised significant power—and a unifying religious ideology, which linked the pharaohs to the gods. As Egypt transitioned from the period of unification under King Narmer to the Old Kingdom, the king and the elite became increasingly wealthy and powerful. They further developed earlier systems of tax collection, expanded the religious doctrine, and built a huge state bureaucracy.

Social distinctions and hierarchies remained fairly consistent through all of dynastic Egypt. Most people were rural peasant farmers. They lived in small mud huts just above the flood plain and taxes were paid in agricultural produce. When they weren’t farming, they were expected to perform rotating service for the state, by, for example, working on a pharaoh’s tomb, reinforcing dykes, and helping in the construction of temples. The labor of the majority of the population supported the more elite and skilled classes, from the pharaoh down through the governing bureaucrats, priests, nobles, soldiers, and skilled craftspeople, especially those who worked on pyramids and tombs.

The status of women in dynastic Egypt was relatively equal to that of men. At least compared to women in other ancient societies, women in ancient Egypt had considerably more legal rights and freedoms. Men and women generally had different roles; Egyptian society charged men with providing for the family and women with managing the home and children. These ascribed gender roles meant that women were usually defined primarily by their husbands and children, while men were defined by their occupations. This difference could leave women more economically vulnerable than men. For example, in the village of craftspeople who worked on the pharaoh’s tomb at Deir el Medina, houses were allocated to the men who were actively employed. This system of assigning housing meant that women whose husbands had died had to leave their homes as replacement workers were brought in. Despite some vulnerability, Egyptian law was pretty equal between the sexes when it came to many other issues.

Egyptian women could own property and take cases to court, enter into legally binding agreements, and serve actively as priestesses. There were also female pharaohs, most famously Hatshepsut who ruled for twenty years in the fifteenth century BCE. One last, perhaps surprising, legal entitlement of ancient Egyptian women was their right to one-third of the property that a couple accumulated over the course of their marriage. Married women had some financial independence, which gave them options to dispose of their own property or to divorce. Therefore, while women faced constraints in terms of their expected roles and had their status tied to the men in their families, they nevertheless enjoyed economic freedoms and legal rights not commonly seen in the ancient world.

Suggestions for readings:

- “The Teachings of Khety” (2040-1648 BCE),

- Egyptian Love Poetry can be read online or purchased as a hard copy. Most are written by unknown authors and are known by the first line of the poem.

Or, copy and paste these titles into a search engine to find sites:

- “Love, How I’d Love to Slip down to the Pond”

- “My Love is One and Only, Without Peer”

- “Why, Just Not, Must You Question Your Heart?”

- “I Love You Through the Daytimes”

Attribution:

Berger, Eugene; Israel, George; Miller, Charlotte; Parkinson, Brian; Reeves, Andrew; and Williams, Nadejda, “World History: Cultures, States, and Societies to 1500” (2016). History Open Textbooks. 2.

References:

1. Photo by Kathleen J. Hartman, CC BY-NC-4.0 license.

2. Hymn to the Nile, c 2100BCE.” Ancient History Sourcebook Fordham University. http://legacy.fordham.edu/halsall/ancient/hymn- nile.asp

3. Photo by Kathleen J. Hartman, CC BY-NC-4.0 license.

4. Cnes Spot Image, CC BY-SA 3.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=Special:Search&limit=100&offset=1000&profile=default&search=Egypt+nile&advanc edSearch-current={}&ns0=1&ns6=1&ns12=1&ns14=1&ns100=1&ns106=1#/media/File:Nile_SPOT_1173.jpg

5. https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/why-is-egypt-called-the-gift-of-the-nile.htm

6. Author: DanMS at English Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?search=Maps+of+the+nile&title=Special%3ASearch&go=Go&ns0=1&ns6=1&ns12=1&ns14=1&ns100=1&ns106=1#/media/File:River_Nile_route.jpg

7. Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?search=Palette%20of%20Narmer&title=Special%3ASearch&fulltext=1&ns0=1&ns6=1&ns1 2=1&ns14=1&ns100=1&ns106=1#/media/File:Narmer_Palette.jpg

8. Photo 2007 by Kathleen J. Hartman, CC BY-NC-4.0 license.

9. CC0 https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=Special:Search&limit=100&offset=100&profile=default&search=ostracon&advancedS earch-current=%7B%7D&ns0=1&ns6=1&ns12=1&ns14=1&ns100=1&ns106=1#/media/File:Hieratic_ostracon_MET_14.6.216_front.jpg

10. Author: Andreas Praefcke, Source: Wikimedia Commons, License: Public Domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?sort=relevance&search=Andreas+Praefcke+Egypt&title=Special%3ASearch&profile=advan ced&fulltext=1&advancedSearch-current=%7B