4.11 CLASSICAL GREEK SCULPTURE

OVERVIEW

It is important to remember that the ancient Greek sculpture that can be viewed today is limited to those relatively few pieces that have survived. For this reason there are only a few of the bronze sculptures, the most valuable and noble of the genre, left for our viewing. Bronze was and still is worth a lot, whether it be in money or trade. Consequently, bronze statues, the most important as the Greeks would have seen it, were melted down by later generations and cultures. In most cases they were turned into weapons. Whether made of bronze or marble, Classical sculptures reflect the time period in which they were created.

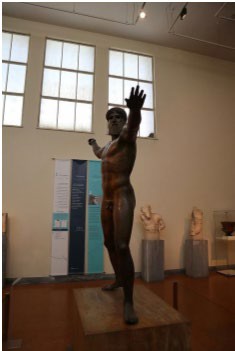

Most of what is known about Classical Greek sculpture comes from the excellent copies made by the Romans. Copies of popular sculptures were made for sale. There are still five extant copies of Doryphorus. Bronze statues were often copied before being melted down. Many of the marble statues that have survived from ancient Greece and from the later Roman era are broken. Marble hardens over time after being carved and can become brittle. Arms and other appendages often break off. Because of this many marble copies of bronzes required extra support for limbs. The bronzes could be designed with arms outstretched like those of Zeus/Poseidon, but that approach cannot be as successful in marble.

Sometimes even statues that were originally carved in marble have supports, especially supports that hold the arms to the body in the Classical era, or supports that appear as large vases or tree stumps during the Late Classical and Hellenistic periods. There are three basic divisions in Classic sculpture, Early Classical, High Classical and Late Classical. Pieces categorized as Early Classical in style are generally dated between c. 480 and 450 BCE. Pieces in the High Classical style are dated between 450 BCE and 404 BCE, the fall of the Athenian Democracy. Late Classical pieces date from 403 BCE to 323 BCE, when Alexander the Great died. Although the statue of Zeus seems open from the front, he seems closed when viewed from the side.

Zeus is an excellent example of a transition piece. He is more closed from one view than later Classical work but he is more open than the Archaic Kouroi that came before him. Both copies and originals have been separated from their context. This adds another layer of confusion to those attempting analysis. Fortunately, Athens managed to retain many of the works from the Classical age, and in the case of the acropolis, much of it can be connected to its original context.

PERSONAL VERSUS PUBLIC ART

The majority of the art from the Classical era that is still available for viewing was commissioned by the City-State that displayed it. As such, it was large and monumental. Consequently, most sculpture that can be studied from the age was public art, which had an agenda to honor the gods or later, to honor the Athenians, as seen on the Parthenon.

Personal art from the Classical era is made up of small sculpture that few could afford. This type of sculpture was household items such as perfume bottles, hairpins and mirrors, such as this brass mirror. Wall paintings were also popular but none have survived.

The Parthenon displays the two major types of sculpture found in public buildings. The first is sculpture in the round. While much public art used bronze sculptures that were designed so that a person could walk around them, the Parthenon pediments presented marble sculptures carved in the round, even though they would only be viewed from one angle, from below and from the front. This search for excellence is perhaps a reflection of Athenian idealism.

The other type of public sculpture was bas-relief, which is carved on a flat surface so that it can only be viewed from the front. The Metopes that decorate the exterior colonnade are in high relief (deeply carved,) whereas the frieze that decorates the interior colonnade is carved in low relief (shallowly carved). As you view the art of the classical age, think

about how it reflects the era in which it was created. Was it an early piece like the statue of Zeus, or was it a late piece from after the fall of the Democracy? Look for hints in the use of the elements of art.

Early classical sculpture tended to :

- Be more open than previous sculpture

- Contain a subtle contrapposto pose

- Demonstrate Humanism, Rationalism and Idealism

- Celebrate arête, (excellence and moral virtue) bravery, beauty and repose. The figure often stood alone, filled with potential.

Zeus is a great example of the Early Classical style, as is Kritios Boy, while Athena in image 4.101 and Zeus behind her below on the right are in the high Classical style. The differences are subtle.

High Classical sculpture tended to:

- be more open than Early classical sculpture,

- contain a clear contrapposto pose, normally more exaggerated than in Early Classical sculpture,

- demonstrate Rationalism, Humanism and Idealism, be designed to be viewed from multiple angles,

- and celebrate bravery, arête, beauty and repose.

Late Classical sculpture tended to:

- be taller and leaner in proportion than Polykleitus’ Canon (now called, Doryphorus),

- incorporate stumps, vases and other “props,”

- be more erotic than Classical work, especially where images of women were concerned,

- and be more personal than earlier Classical statues.

In each era the art is distinctive and is tied to the context in which it was created. With a bit of effort, these pieces can be read. The values and hopes of the people who created the images can be seen reflected in them. For more information of each of these art styles, read the sections and view the video clips associated with them.

Early Classical Sculpture

The Early Classical style is sometimes called, The Severe style, which is odd as it is not nearly as severe as the earlier Archaic Style. This early Classical style describes the trends in Greek sculpture between c.490 and 450 BCE. Artistically this stylistic phase represents a transition from the rather austere and static Archaic style of the sixth century BCE to the more idealized Classical style. The “Severe style” or “Early Classical style” is marked by an increased interest in the use of bronze as a medium as well as an increase in the characterization of the sculpture, among other features.6

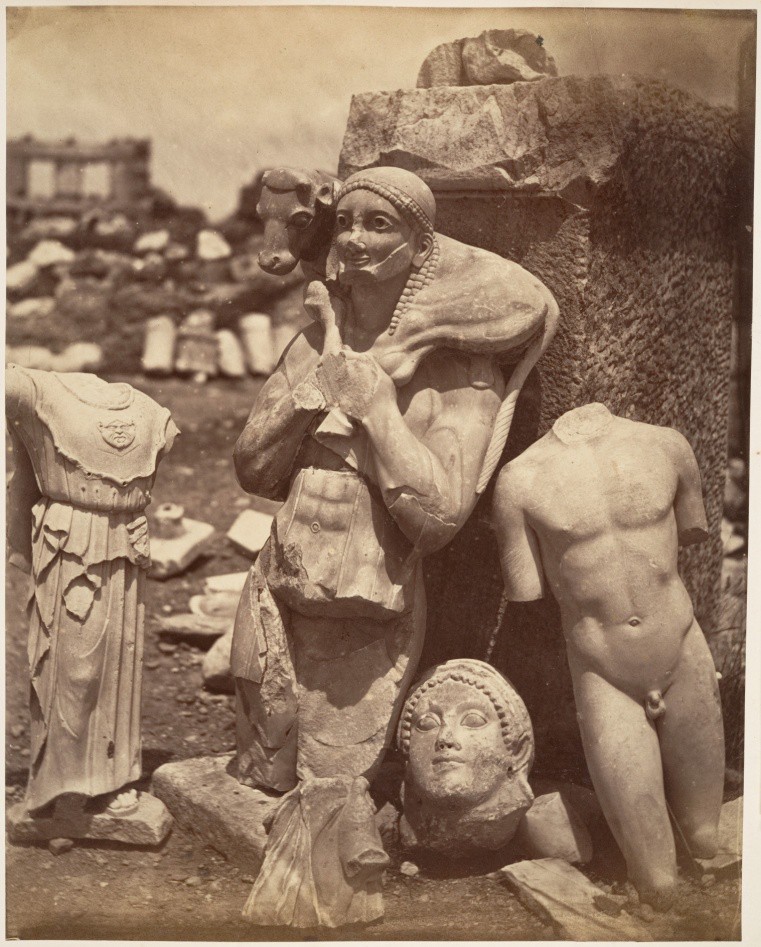

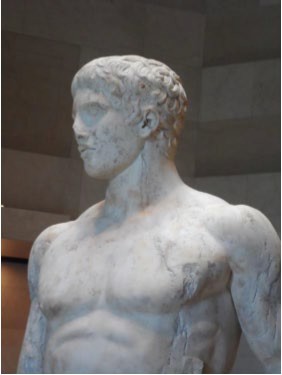

The earliest sculpture that clearly presents the idealism, humanism and rationalism of the Athenian Democracy was probably created in marble by the famous bronze sculptor, Kritio. Because of this the statue is known as Kritios Boy. This statue has become the beacon that announces the beginning of the Greek Classical age.

View the following video to better understand how this statue differs from his Archaic cousins. As you view the upcoming video, ask yourself, how can idealism, humanism and rationalism be perceived in the sculpture? These are the cultural values that identify Classic sculpture. See if you can identify how they appear in Kritios Boy.

See the following link: KRITIOS BOY VIDEO8 (5:58)

If you have difficulty viewing the video above, use this link https://smarthistory.org/kritios-boy/.

There is a sense of impending movement in this statue. Such focus on potential lends itself to idealism. As a symbol, rather than a picture of an individual, the youth of the statue also suggests idealism as the figure is at the strongest, and most beautiful that he will be in his life. He is at his physical and mental peak.

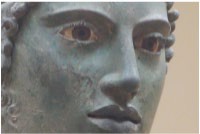

The Archaic smile is gone and in its place is a look of calm, rational thoughtfulness. The boy stands like a living human. His muscles are flexed and tensed as he prepares to move forward into the space of the viewer. He is fully human and as such, is a celebration of the beauty, reason and potential of the Democratic, Athenian citizen. Just before the time that Kritios Boy was carved, advances in metallurgy, led to the casting of bigger than life bronze statues. Statues could now be cast in pieces, allowing glass paste eyes (ivory and onyx were also used) to be added from inside the head. This created a more natural look than what is seen on Archaic sculpture, where the eyes sit on the surface of the face.

Notice that the sculptor took the same approach to carving this marble statue. Perhaps the artist, who specialized in casting bronze, wanted to test the same approach with marble. It is evident that the sculpture’s eyes would have been added in a more life-like medium. Unlike the bronze statues of the time, however, supports had to be added to help maintain the position of the arms. Unfortunately, this did not prevent the statue from being broken into pieces during the Persian invasion of the Athenian Acropolis (refer to video). This fragility may explain why this method is rarely seen in marble sculptures.

Kritios Boy has the relatively small genitals and relatively large head that brings a viewer’s focus to the importance of the head and the use of the reason that resides within it. This intentional manipulation of size served as a symbol of the rational mind ruling over the carnal body.

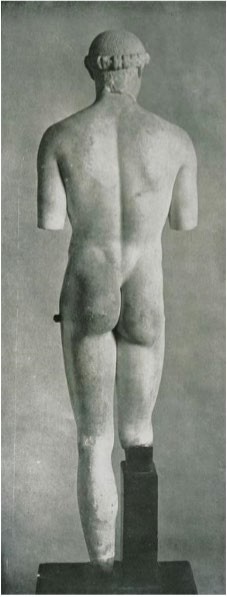

Although his weight shift is subtle, in the front view, Kritios Boy demonstrates the potential of idealism along with presenting a human looking body with a rational expression. He is purely Classical.

Viewing Kritios Boy from the rear reveals the s-curve formed by the backbone and completed by the turn of the head. This s-curve indicates the potential for movement, as the weight shift causes parts of the body to be counter-positioned. This position is referred to as contrapposto. The head turns to the side, the torso faces front and the hips tilt, as human hips do when one is about to step forward. Kritios Boy is technically a kouros, as he is a naked male standing alone and stepping forward. The style and intent are so different, however, that the term ceases to be used in this period.

As one analyzes sculpture, one will often find the statues broken, particularly if they are carved from marble. Over time, marble hardens as the air surrounds it after carving. Unfortunately, it can become brittle and break when stressed.

While the video does a great job of discussing this statue, it fails to mention the hair. Did hairstyles change, or was the long plaiting of the Archaic kouroi a stylistic element? In either case, the hairstyle of Kritios Boy is like that of contemporary (in the same time period) Greeks. Kritios Boy seems younger than the archaic kouroi. Could this be because the men who were left to fight and defend Athens were younger? It is possible that the ideal is depicted as younger because so many men were lost to the Persian war. Or perhaps his age is to remind the viewer that the ideal human has potential.

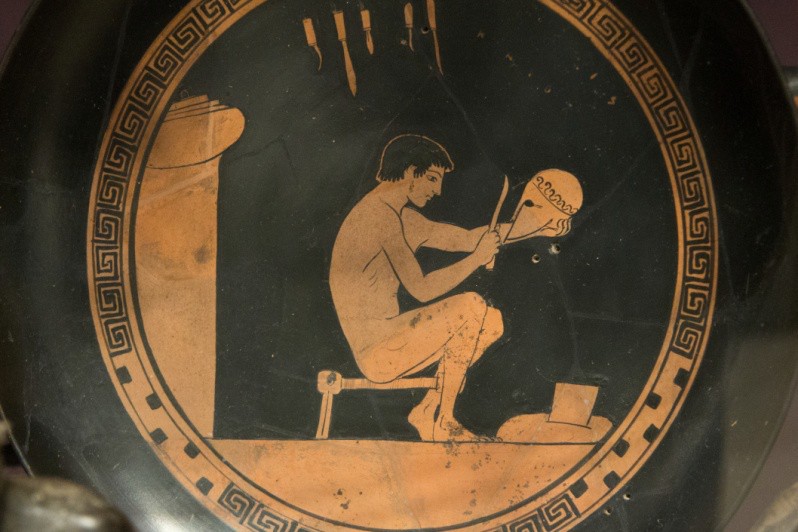

The Classical elements seen in the Kritos Boy can also be perceived in this piece of pottery, created the same year. Notice that there is an attempt to demonstrate depth as one leg is placed in front of the other. There are indications of muscle structure that illustrate the growing sense of humanism in mainland Greece. The Archaic smile is gone, replaced by a look of intense concentration. Red figure pottery allowed potters to paint in more detail than black figure pottery, allowing more emphasis to be put on muscle structure, rational expressions and movement.

See the following link to learn more about “the severe style” that creates a transition from the Archaic style to the Classical style.

NIOBID KRATER.14 (5:51)

If you have difficulty viewing the video again, use this link https://smarthistory.org/kritios-boy/.

Below is an image of the Charioteer of Delphi, a part of a larger sculpture that was cast in the Early Classical style. Can you identify what makes this sculpture Classical in style?

Notice how much the image of a Charioteer has changed since the Geometric period. The image above displays frontal stiffness and an outsized head. The Classical Charioteer demonstrates naturalism and displays rationalism through expression and body stance, rather than through size distortion. There is no way to tell if the Geometric Charioteer was part of a larger sculpture group. The differences between the two styles, however, are obvious.

Although it is difficult to see in these pictures, there is evidence of silver in the headband. The eyes are glass paste and would have looked strikingly real when they were fully intact. The figure even has finely worked bronze eyelashes. This bigger-than-life sculpture has carefully crafted feet, even though they would have been invisible to the public. The figure would have been lifted above eye level as it stood in the chariot.

Every detail has been carefully created. Bronze was far too valuable to cover with paint and paint would not have lasted long as there were no binders that would allow it to stick to metal in the fifth century BCE. Even though no paint would have been used on this figure, it was polychromatic in its incorporation of silver, glass and copper inlay. This type of casting was expensive and difficult which indicates the importance of the image

There is a weight shift indicated by the contrapposto stance. The twist is caused because the figure’s feet face in a different direction that his face. This twist is subtle but effective in giving the figure a sense of humanity and life. He stands proudly, ready to do his part for his community. He displays potential, is calmly beautiful, and he is very human.

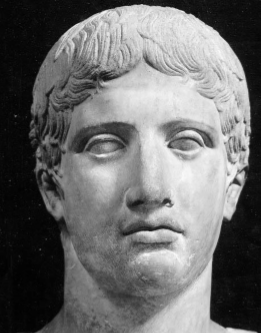

RIACE WARRIOR

Another great example of the Early Classical style in bronze casting is the Riace Warrior. The attention to detail is impressive. This life sized bronze statue has silver foiled teeth and copper inlay for lips and nipples. He has brass foiled eyelashes and ivory whites in his eyes. It is likely that his pupils were glass or precious stone. As well as being durable and allowing great detail in sculpture, bronze statues had a polish that resembled the shine on skin that had been treated with olive oil. Athletes covered themselves in olive oil much like body builders do today. It showed off the musculature, emphasizing body strength and beauty. Bronze exemplifies the beauty of the human form at its most ideal.

The Warrior’s beard is nearly perfect in its symmetry and unlike the body, is not shiny but textured in perfect curls. The beard indicates age and wisdom, a trait also associated with Zeus. This warrior is indeed godlike in his perfection. He seems about to take a breath with his lips slightly parted. It appears that this warrior had a shield on his right arm and like the Spear Bearer held a spear that brought attention to his head. Bronze sculptures were made using the lost wax method. The bronze is relatively thin and the statues are hollow. In every case, the sculptures point to a change in style and technology that accompanied a change in culture. As the ancient Greeks began to focus on the potential of human beings, politics, religion, art followed suit.

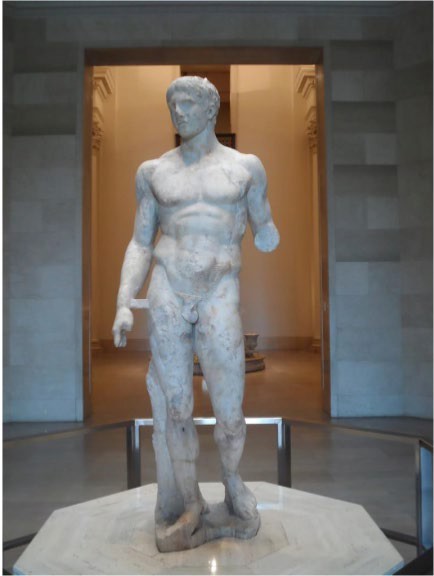

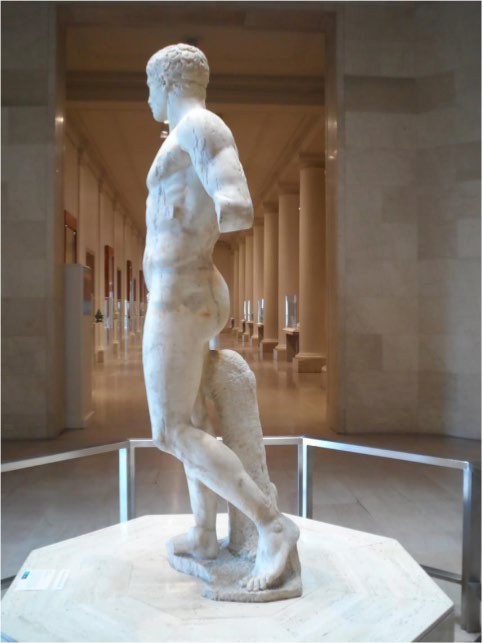

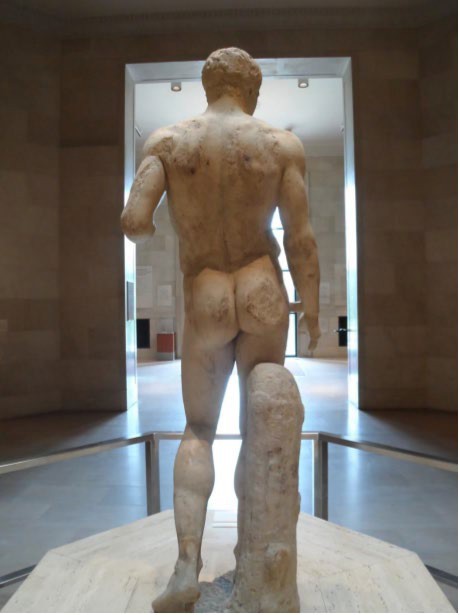

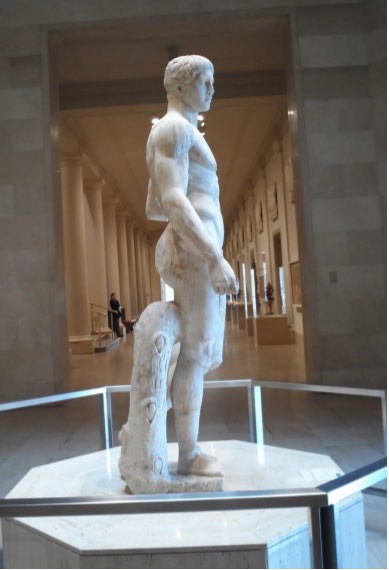

THE SPEAR BEARER, A NEW STANDARD

Polykleitos was a fifth Century BCE sculptor best known for the sculpture that is currently referred to as, Doryphoros or The Spear Bearer. The sculpture, first produced in bronze, is called this and it can be assumed that he originally held a spear in his upraised hand. (Note the supports that the Romans had to add to the marble copy). Polycleitus, however, called the sculpture, Canon. The term, canon, is not a reference to a weapon, but a reference to a measuring standard, in this case, for the ideal human form. Doryphorus is a symbol of the ideal Greek citizen, brave, free and beautiful. Look what was accomplished when the Greeks went up against the larger numbers of Persians and won, against all odds. Surely this was because Greeks were free! Of course they had defeated the slaves fighting for Xerxes. Anyone answering to a king would have been considered a slave by these Democratic and Republican Greeks. They had thrown off their tyrants and formed governments that included the voices of citizens, limited though the citizenship was.

Here in bronze stood an image of the perfect citizen, ready to fight for his city- state. The Classical Greeks were idealists. They sought perfection in body and mind. The success of the new Democracy and Republics in fighting off the Persian invasion inspired a growing interest in human potential. Doryphoros is not rigid and symmetrical as the Kouroi tended to be. Like Kritios Boy, Polykleitos’ Doryphoros stands in a contrapposto pose. In other words, he is counterbalanced. He puts weight on one foot while keeping the other relaxed, as though he is about to step forward. The arm above the active foot is relaxed and the arm above the relaxed foot reaches up to hold a spear. It bears his weight as he leans on his spear.

This counter positioning (contrapposto) creates an s-curve completed by the turning of the head. This curve and the diagonal line created by the spear would have created a sense of movement, as potential energy seems about to be released. This indication of potential ties in nicely with the attempt to present an ideal, rather than a completely symbolic or realistic image.

Doryphorus is a symbol of the focus on potential. There are no elements of the sculpture that identify him as an individual. The Spear Bearer stands alone, a symbol of bravery, harmony and beauty. He is, quite literally, bigger than life. Measuring 78” x 19” x 19” he was a good deal taller than the average Greek man, but not so large as to be inaccessible. (Humans are more than a foot ½ taller on average than they were in 450 BCE.) Even by today’s standards, however, 6 1/5 feet is far from petite.

The Spear Bearer represents an abstract ideal of perfection. No flaws can be seen on his body. He is eternally young, at the height of his health and beauty. Doryphorus looks forward into the distance as if planning where to go next.

He is about to move, indicating his potential for action. His expression is calm and harmonious like his stance. The calm expression reminds the viewer that the ideal Greek is a man of reason. He does not become emotional when challenged with circumstance, or by an enemy.

The sense of movement and the naturalism are indications of how the Greeks were honoring humans. In Democratic Athens, as well as in the neighboring Republics, the ideal man served his community. This warrior displays the importance of being a part of his community through his service as a warrior. He demonstrates the growing sense of humanism developing in Athens and elsewhere in Greece.

As well as demonstrating Idealism and Humanism, Doryphorus demonstrates the importance of reason. Notice that his head is a bit large and his genitals are quite small. This is not because Greek men were big headed or because they had tiny genitals. This presentation illustrates the importance of the head, versus the more base instincts suggested by the genitals. The triangle shape created by his body and his spear brings focus to his head, which is at the top of the triangle, where the eye is led. At the apex of the triangle is the most important part of man, his head, where reason resides. His eternal beauty is based on reason. He is beautiful, brave and free, as any decent Greek would have been proud to be.

For a clear comparison of this classical sculpture to an Archaic Kouros, watch the following video:

POLYKLEITOS, DORYPHOROS (SPEAR-BEARER) (6:04)

If you have trouble viewing the video above, use this link: https://smarthistory.org/polykleitos-doryphoros-spear-bearer/.

References:

1. Bronze statue of Zeus or Poseidon. Sharon Mollerus, CC BY 2.0 https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia /commons/f/f5/Bronze_Statue_of_Zeus_or_Poseidon_%283423215449%29.j pg

2. Walters Art Museum, Public domain, https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/9/90/Greek_-_Caryatid_Mirror_with_Aphrodite_- _Walters_54769.jpg

3. CC BY-SA 3.0 https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/9/94/009MA_Kritios.jpg

4. Photo by:shako, CC BY 3.0 https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/4/41/Castings_of_classical_Greek_sculpture_in_the_Pushkin_Mu seum_01_by_shakko.jpg

5. Photo by José Luiz Bernardes Ribeiro https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/1/18/ Aphrodite_ of_Knidos_%28GL_288%29_-_Glyptothek_- _Munich_-_Germany_2017.jpg

6. Dr. Jeffrey A. Becker, “Riace Warriors,” in Smarthistory, August 8, 2015, accessed August 2, 2019, https://smarthistory.org/riace- warriors/.

7. Metropolitan Museum, CC0, https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/0/01/-The_Calf- Bearer_and_the_Kritios_Boy_Shortly_After_Exhumation_on_the_Acropolis-%3B_Danseuse_du_Temple_de_Bacchus_MET_DP150943.jpg

8. Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris, “Kritios Boy,” in Smarthistory, December 13, 2015, accessed August 2, 2019, https://smarthistory.org/kritios-boy/.

9. Photo by Tetraktys, CC BY-SA 2.5 https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:009MA_Kritios.jpg

10. Critius, CC BY-SA 2.5 https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/d/de/ACMA_ 698_Kritios_boy _5.JPG

11. Critius, CC BY-SA 2.5 https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/4/49/ACMA_698_ Kritios_ boy_ 4.JPG

12. Photo courtesy of Kathleen J. Hartman. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

13. Photo by Zde, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/f/fc/Artisan%2C_red- figure_pottery%2C _480_ BC%2C _AshmoleanM%2C_142566.jpg.

14. Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker, “Niobid Krater,” in Smarthistory, December 15, 2015, accessed August 2, 2019, https://smarthistory.org/niobid-krater/.

15. By Berthold Werner, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/0/05/Delphi_BW_2017-10-08_10-08-55.jpg

16. Drawing, Charioteer. Joyofmuseums, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons /8/8a/Charioteer_of_Delphi_-_Delphi_Archaeological_Museum_by_Joy_of_Museums_-_5.jpg

17. Photo by Zde, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/a/ab/ Charioteer%2C_small_bronze%2C _geometric_ period%2C_A M_Delphi%2C_Dlfm404.jpg

18. Photo by Gunnar Bach Pedersen, Public domain, https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/8/ 88/Vognstyreren-fra_Delfi2.jpg

19. Copyright © 2004 David Monniaux, CC BY-SA 1.0 https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/8/8b/Delphi_charioteer_front_DSC06255.JPG

20. Photo by Luca Galli from Torino, Italy, CC BY 2.0, https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons /0/0b/ Riace_bronzes_-_Statue_A_%28detail%29_- _National_Archaeological_Museum_of_Magna_Graecia_in_ Reggio_Calabria_-_Italy_-_14_Aug._2014.jpg

21. Photo by A. Ismoon, (Fichier:Museo Magna Grecia 10.jpg Photo retouched, cropped, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/f/f0/Museo_Magna_Grecia_102.jpg 16

22. Photo by Effems, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/f/f1/ Museo_Magna_ Grecia_08.jpg

23. Photo by Effems, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons /8/8f/Museo_ Magna_ Grecia_18.jpg

24. Photos courtesy of Kathleen J. Hartman. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

25. Photos courtesy of Kathleen J. Hartman. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

26. Photos courtesy of Kathleen J. Hartman. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

27. Photo courtesy of Kathleen J. Hartman. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.