9.3 Islamic Culture and Influence

The world owes a debt to Islamic scholars for their advances in the sciences and learning. In addition to those, we can be grateful that we have the writings of the great Greek thinkers because the Arabic scholars translated them from Greek to Arabic and then used the texts to teach in their universities.

This is a brief list of cultural activities for which the Muslims are known.

- 696-Arab coinage is introduced and Arabic becomes the official administrative language of Islam.

- 751- Arabs learn paper making from Chinese prisoners

- 755-Jurjis ibn Bakhtishu’ founds a school of medicine in Baghdad

- 760- Development of algebra and trigonometry

- 830- Greek works translated into Arabic and placed in Bayt al-Hikma (House of Knowledge) in Bagdad, world atlas compiled, sciences flourish

- 925- Medieval Encyclopedia of al-Razi (Rhazes) brings medicine to Europe, including the first medical treatise on smallpox

- 970- The Fatimids build the mosque-university or al-Azhar in Cairo

- 1093- Arab compass is first known to be used

- 1176- Two universities founded in Cairo and Fustat

- 1171- Ibn Rushd (Averroes) writes Middle Commentary on Aristotle

- 1325- Ibn Battuta, travels in Asia and Africa until 1354.

“Early in the 9th century, there was established in Baghdad a foundation called the House of Wisdom (Bayt al-Hikmah), which had its own library. Its purpose was to promote the translation of scientific texts. The most famous of the translators was Hunayn ibn Ishaq al-`Ibadi, a Syriac-speaking Christian originally from southern Iraq who also knew Greek and Arabic. He was the author of many medical tracts and a physician to the caliph al-Mutawakkil (ruled 847-861/232-247 H), but he is most often remembered as a translator, an activity he began at the age of seventeen. He produced a truly prodigious amount of work before his death in about 873 (260 H), for he translated nearly all the Greek medical books known at that time, half of the Aristotelian writings as well as commentaries, various mathematical treatises, and even the Septuagint.

Ten years before his death he stated that of Galen’s works alone, he had made 95 Syriac and 34 Arabic versions. Accuracy and sensitivity were hallmarks of his translating style, and he was no doubt responsible, more than any other person, for the establishment of the classical Arabic scientific and medical vocabulary. Through these translations a continuity of ideas was maintained between Roman and Byzantine practices and Islamic medicine.1

ART FORMS

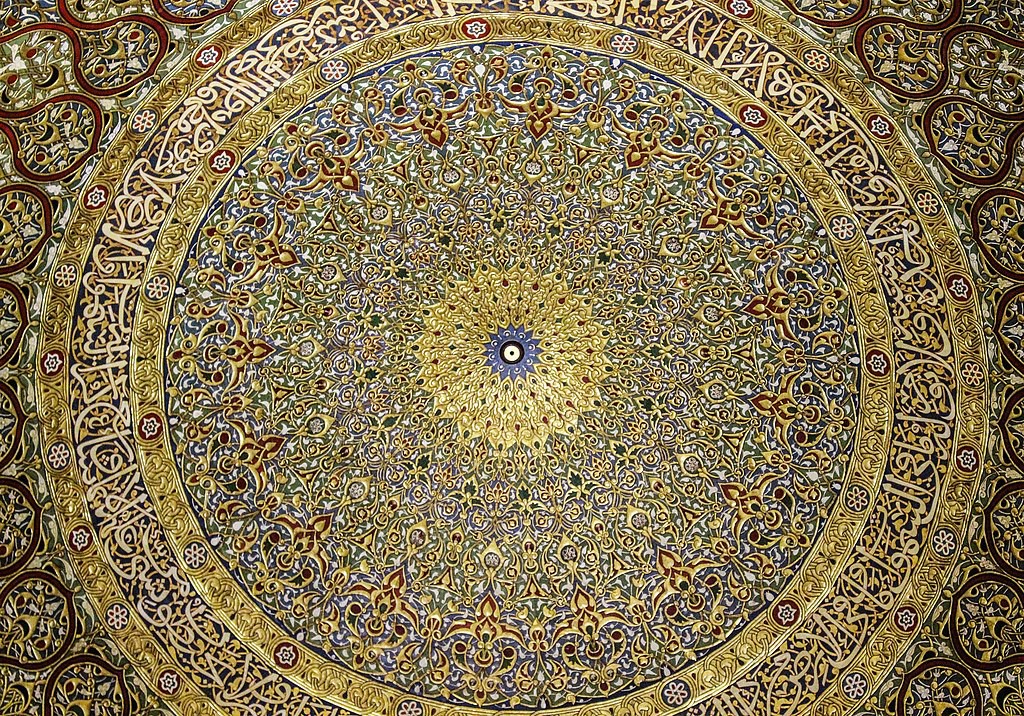

Islamic artisans were quick to absorb ideas and influences from the cultures they encountered. From Greco-Roman architecture came the column and the arcade. From Byzantine architecture came the pendentive which allowed the dome to become a prominent feature of the Islamic mosques. From Persian art and architecture came miniature painting, the vaulted hall, the pointed arch, and floral and geometric ornament. They also had uniquely Islamic ideas and forms. All of Islamic art was affected by the Quran’s prohibition against the representation of living creatures. Large scale paintings and sculptures were not produced and lifelike figures, whether of humans or animals, largely disappeared from art. Because of these prohibitions, artists were very inventive in the use of non-representational forms. The arabesque, a complex figure made of intertwined floral, foliate, or geometrical forms, became a highly visible sign of Islamic culture.

See image 9.13 for an example of the arabesque above the portal of the Great Mosque of Cordoba. The designs were rarely based on nature, but were meant to make viewers think of values other than those of their surrounding world. The minor arts of the Muslims included the weaving of pile carpets, leather tooling, brocaded silks and tapestries, inlaid metal work, enameled glassware, and painted pottery. Most of these products were embellished with complicated patterns. In general, the arts paid particular emphasis to pure visual design.

ISLAMIC ARCHITECTURE

Mosques were the most important of the Islamic buildings, but there are many examples of palaces, schools, libraries, private dwellings, and hospitals. Islamic architects built many more secular buildings than their European counterparts. The principle elements include bulbous domes, minarets, horseshoe arches, and twisted columns, together with the use of tracery in stone, alternating stripes of black and white or red and white, mosaics, and the use of Arabic script as a decorative device.

As in the Byzantine style, comparatively little attention was paid to the exterior decoration. The Arabic pointed arch was adopted by Gothic builders to become one of the main characteristics of the spectacular cathedrals of the 13th and 14th centuries.

The mosque was plain in exterior decoration and rectangular in shape. Special features included basins and fountains for ritual washing, porticoes for instruction, and an open area for group prayers. The dome was often a high melon shape, and a minaret, a thin pointed tower, was included for an official to climb and call the faithful to prayer five times a day.

Interior spaces were richly decorated, reminding the viewer of the beauty of paradise. Brilliant mosaics and rugs were on the floors, calligraphic friezes covered the walls, and overhead metal lamps cast a glow onto the faithful at night.

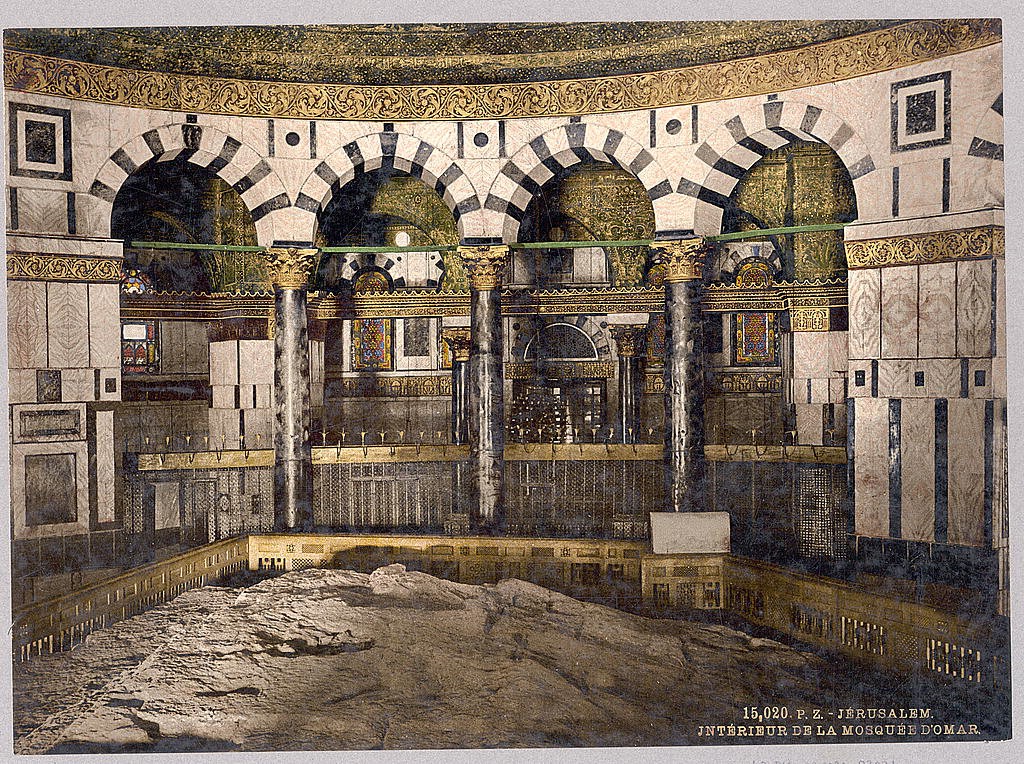

The Dome of the Rock, built in 691 by Abd-al-Malik is one of the most sacred sites in the Muslim world. The small “chain” building in front of the main mosque was created as a model when the Dome of the Rock was being built.

This building has special significance to the people of Islam. It is built over the top of a rock that was supposed to be the same rock where Muhammad prayed when he took his night flight to Jerusalem. See images 9.16 and 9.17. It is also supposed to be the same rock where Abraham was asked by God to sacrifice his son. Christians believe that son was Isaac, and Muslims believe the son was Ishmael. Today the Dome of the Rock is venerated by Jewish and Muslim pilgrims as a holy place.

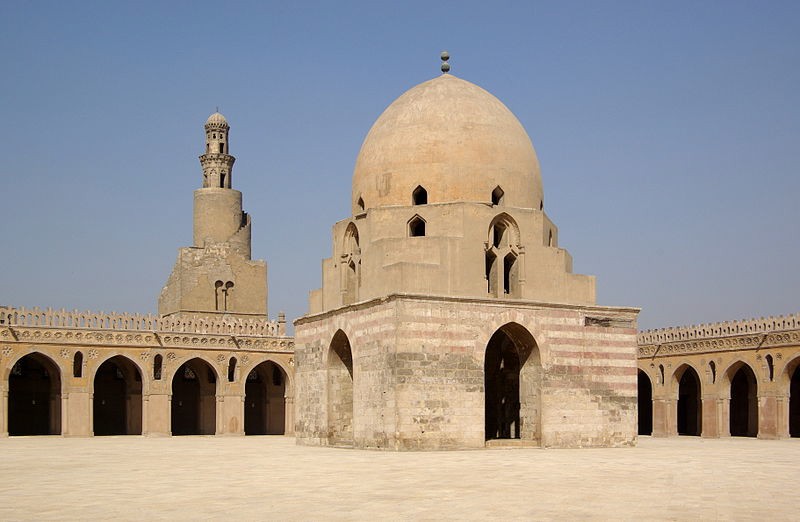

Another example of Muslim architecture is the Mosque of Ibn Tulun built in 876-879. It was built by a governor who founded a short lived Egyptian dynasty in Cairo, independent of the caliphate in Baghdad. It is the best preserved monument of the luxurious Samarran Age and was restored in 1296 by the Mamluk Sultan Lajin to fulfill a vow. This mosque became the model for many other mosques which were later built throughout the Islamic civilization.

The mosque covers 6 1/2 acres of land and is rectangular with passageways on three sides that lead through an arcaded area into a central courtyard dominated by a domed fountain. This building is built entirely of brick and then covered with plaster, even though Egypt (unlike Iraq and Iran) had plentiful sources of stone. The fountain was used as a place to perform the wudu, before entering the sanctuary. There is no monumental gateway and entrance to it was through many doors on all sides.

The crest along the top of the wall looks like paper dolls with joined hands, and may have symbolized the militant, united Muslim community guarding the walls of the House of Islam. See image 9.19. Notice how they are stylized human forms rather than actual depictions of humans. This may have been “a nod” to the rule prohibiting the creation of living forms in art. The minaret is made of stone and dates from 1296. The original one was made of brick and was a simple round spiral probably inspired by the ziggurats standing in 9th century Iraq. The square tower topped by two octagonal stories is typical of the 13th century minaret style, but the staircase on the outside, rather than the inside, imitates the original 9th century structure. The minaret was used by the muezzin to call the faithful to prayer.

The doors were made of wood with bronze plates and studs affixed. The mosque was at a higher level than the outer courts. Below the crest is series of discs in squares of Persian-Mesopotamian derivation which symbolize the captured shields that were hung on city walls after a battle. The rosette design seen in image 9.20 is an old Mesopotamian and Persian motif, imported from Iraq. The interior ornamentation consists of full and half palmate forms as well as pearl borders which came from Samarra. The ceilings were made of palm-log rafters, coffered with panels of sycamore wood.

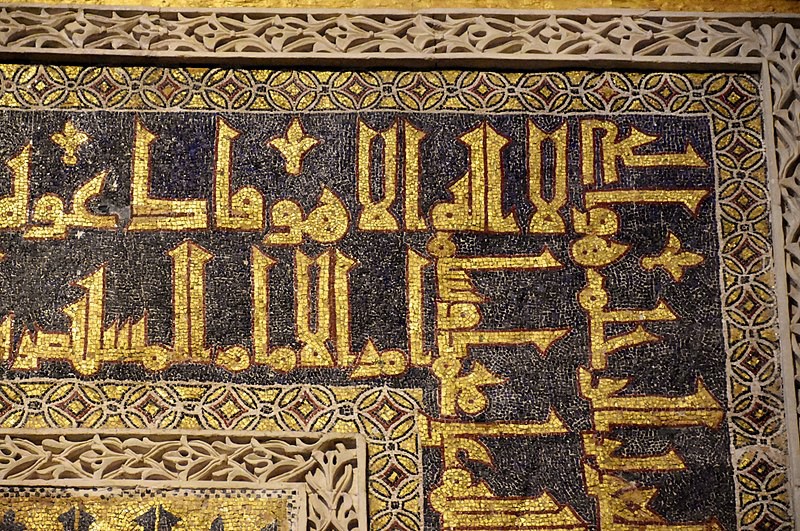

The main area of the mosque is accessed through a series of arcades in that allow access to the mihrab. Notice that some of the arches are slightly pointed and some take on the horseshoe shape. Pilasters are carved into the corners and appear to support the arches. Note the green rugs on the floor that are to be used for prayer during the services. The mihrab is a central focus of the mosque. All who come to pray face the mihrab, which marks the qibla, or the direction of Mecca and the Kaaba. The inner core of the mihrab, that is the marble paneling, the glass mosaic frieze and the wooden hood, come from the 13th century restoration, but the outer case belongs to the 9th century. It is framed with Byzantine capitals and capitals. This photo, 9.23, also shows the minbar, which is a short flight of steps used by a speaker to access the platform and talk after the prayer service. The message above reads “There is no god but God; Muhammad is the Messenger of God, may God bless him and give him peace.”

POTTERY

As Muslims conquered Persia, Byzantium, Egypt, and Mesopotamia they incorporated the methods, materials, and styles of the cultures they absorbed. Unlike some of the cultures they conquered, Islamic ceramicists were not so interested in the shape and form of the object as they were in the surface area to be ornamented. Because of this, much of their pottery is simple in shape but beautifully glazed. Luster decoration was an Islamic technical innovation which probably was first used on glass in Egypt and was adapted with great success to ceramic glazed-ware in 9th century in Iraq. Luster is a rich and hazardous form of decoration, in which the iridescent effect of gold results from metallic particles fired onto the surface of the vessel.

Images 9.24 and 9.25 show luster bowls. Notice the human and animal forms are not quite human or animal and remind us of the early 20th century artistic styles that stretched and altered the human form in multiple ways. The use of overall patterns shows the Islamic artists’ love of covering the entire surface with ornament, partly because of the “horror of a vacuum,” and because more surface decoration provides more scintillation or sparkle. Luster was a luxury ware, and had been used by the princely courts but it later found a market with the middle class. Not all pottery used the luster finish, as it was for the wealthy and it was dangerous to make due to the fumes.

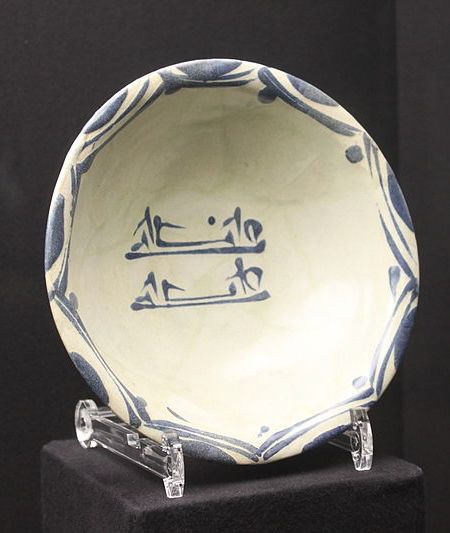

Other Islamic also beliefs impacted the decorations they used in their pottery. The rules in the Hadith prohibited eating or drinking from gold or silver vessels, so pottery and glass were used instead. Muslim artisans also turned to calligraphic text as decorations on their glazed-ware, just as they did to decorate their mosques. The text might be a phrase from the Quran or it might be a line of poetry such as is seen on the bowl in image 9.6 The Kufic inscription reads: “Magnanimity has first a bitter taste, but at the end it tastes sweeter than honey. Good health [to the owner].” It is made of terracotta with a white slip ground and has slip under glaze decorations.

In about the 9th century, Islamic potters saw some of the works of Chinese artisans. Chinese potters had access to very fine clay, which enabled them to create fine, hard china, hence the term “china”. Artisans in most of the Islamic world did not have access to that, so they rediscovered the ancient technique of using tin. They learned that an oxide of tin can be painted on the object, and then the object can be painted with color. When the firing process is done, the heat melts the colors and the tin into a reflective, glowing glaze. Tin glazes were used to make tiles and as a glaze for pottery. This process evolved into the beautiful and popular Spanish Majorca ware we see today.

MANUSCRIPT ILLUMINATION

Manuscript Illumination probably developed accidentally, as a by-product of their practice of translating and copying illustrated Greek scientific texts. By the year 1200 the art of illustrations was fully developed, mostly in Iraq and Iran.

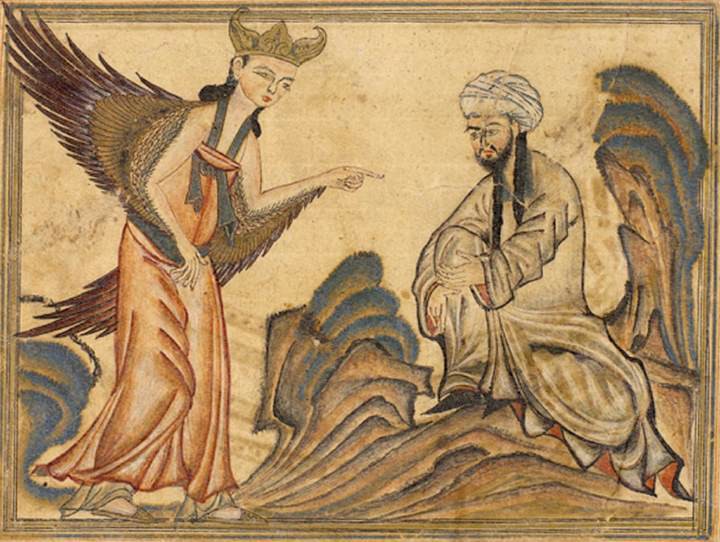

Persian rulers were lovers of fine books and maintained at their courts not only skilled calligraphers, but also some of the most famous painters. Although the painters were Muslims, the orthodox rules regarding the restrictions against portraying living beings were liberally interpreted by them and did not affect their secular arts. Within the framework of illustrating specific stories, the scenes of their life of pleasure such as the hunt, the feast, music, romance, and battle scenes fill the pages of their books. In them we feel the luxury and the splendor of the sumptuous courts of the Mongol sultans who had replaced the caliphs as rulers in the 13th century. There were strong Chinese influences. For instance, since the Chinese had invented the use of paper and the Persians were geographically close, the Persians began using paper as early as the 8th century. Persians also got their inks from China and used many of the same colors used by the Chinese. Ink could be made of ground mineral ore, vegetable matter or sometimes insects. Typically a picture might be outlined in black ink and then the color filled in. They also pounded gold or silver to a thin “leaf” and then pound it with glue to make a paste. This then became the basis for gold or silver paint. Keep in mind that silver tarnishes, so manuscripts which were painted with silver paint turned black with age. Extremely fine brushes might be made of charred twigs, squirrel fur, pigeon feathers and silk thread.19

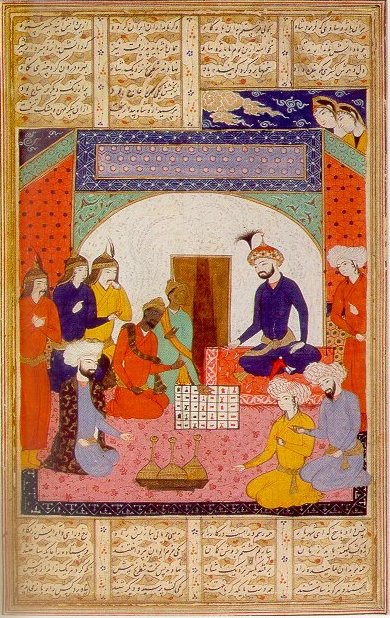

The Treatise on Chess in image 9.30 is from a collection that tells the story about ambassadors from India who bring a chess game to the Chatrang Khosrow, the King of Persia. The book illustrates how the king learns to play the game from his visitors from far away.

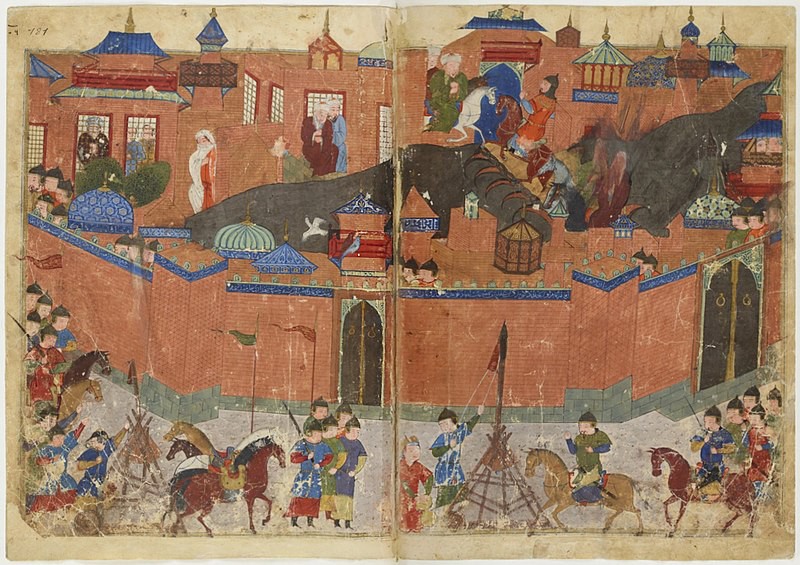

The Mongol siege of Baghdad lasted about 12 days in the winter of 1258. A ditch was dug around the city and catapults and siege engines were used to batter the walls. The city was sacked and the great library, the House of Wisdom was destroyed. The city was left nearly empty, and it is considered by many to be the end of the Golden Age of Islam.

Image 9.32 is a miniature painting on vellum from the book Jami’ al-Tawarikh, literally “Compendium of Chronicles” but often referred to as The Universal History or History of the World, published in Tabriz, Persia. It is now in the collection of the Edinburgh University Library, Scotland.

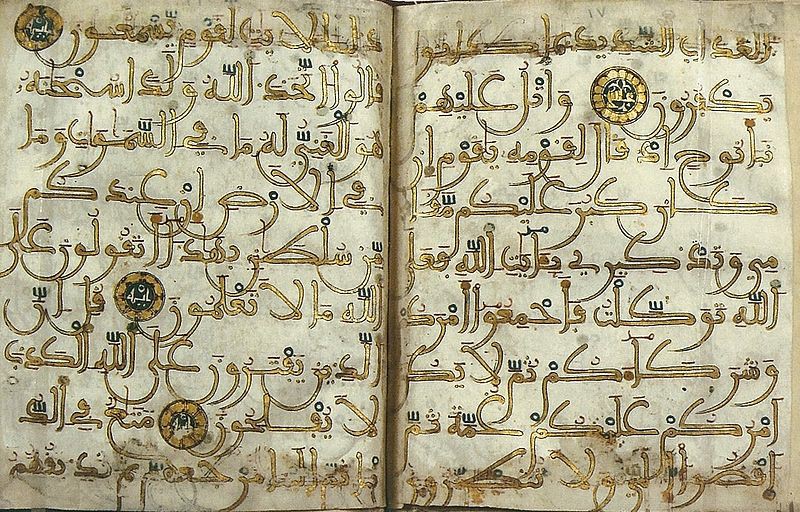

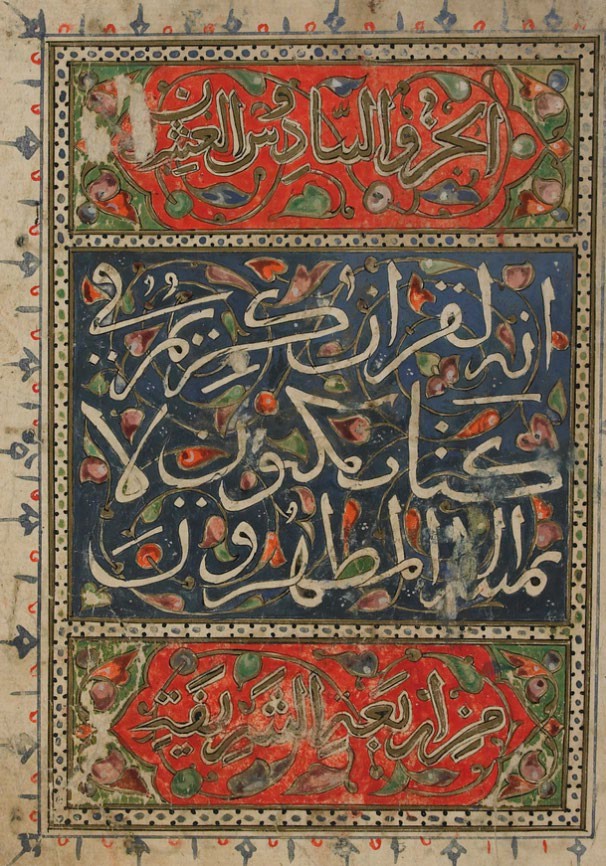

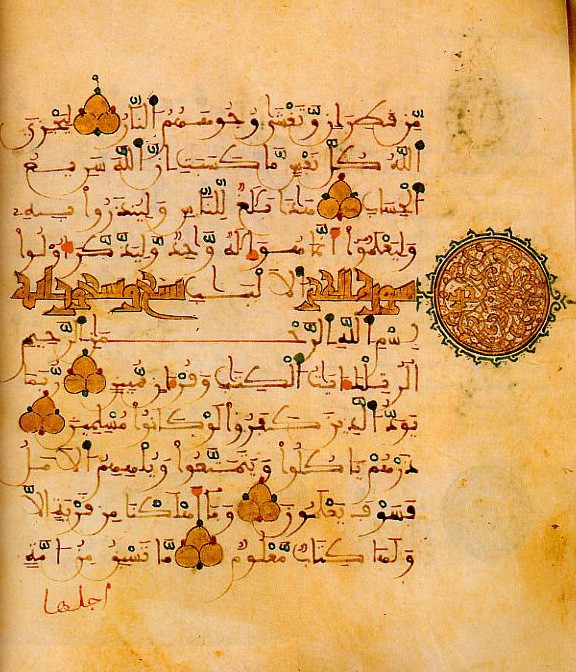

THE QURAN –CALLIGRAPHY AND ILLUMINATION

The creation of the universe and the creation of calligraphy are interconnected. Written language, according to Muslim belief aided in the creation of all other things. The Quran is uncreated, which means that it is a form of God, or at least of the presence of God, and therefore it is perfect. No mistakes are possible, no changes are allowed. Many of the calligraphers and not a few of the illuminators would have known the Quran by heart from beginning to end. Even when they didn’t know it from memory, the passages would have been very familiar. The Quran is written in Arabic and consists of 114 suras, or chapters, which vary in length from a few lines to many verses. The earliest passages are the impassioned words of an embryo prophet as he appeals to his countrymen to return to the word of God. In the second group the unity of the Godhead is proclaimed, idolatry is denounced, and vivid pictures are drawn of judgment, heaven and hell. In the third group Muhammad lays stress on the divine character of his mission. In the next group, the Mecca suras, is found a militant Islam appealing to judgment by the sword. Finally, in the Medina suras, Islam is triumphant; fasts, festivals, and the pilgrimage to Mecca are instituted, and the slaughter of infidels is authorized.

The Quran offers natural opportunities for illuminators. The most obvious of these are the sura headings, and the divisions between the verses. There are also decorative indications in the margins that 5 or 10 verses have passed and places marking times in the reading when prostration is required.

You might enjoy this video about medicine in the Islamic world (20.23). This would be especially good if you are in a medical degree track.

If you have difficulty viewing this video, use this link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z9CIZwTtNRY.

Attribution:

Berger, Eugene; Israel, George; Miller, Charlotte; Parkinson, Brian; Reeves, Andrew; and Williams, Nadejda, “World History: Cultures, States, and Societies to 1500” (2016). History Open Textbooks.

References:

1. https://cmes.arizona.edu/sites/cmes.arizona.edu/files/Student%20Handout.pdf

2. Photo by Richard Mortel, CC BY 2.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Great_Mosque _of_Cordoba,_ mihrab_ area,_10th_century_(33)_(29808902066).jpg

3. Photo by Richard Mortel, CC By 2.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File: Great_Mosque_of_Cordoba, _mihrab _area,_10th_century_(25)_(29210295663).jpg

4. Photo by Andrew Shiva, CC BY-SA 4.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Jerusalem-2013-Temple_Mount-Dome_of_the_Rock_%26_Chain_02.jpg

5. Library of Congress, 1890, photomechanical print, Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File: The_rock_ in_the_Mosque_of_Omar,_Jerusalem_LCCN2003653103.jpg

6. Photo by Bashar Nayfeh, CC BY-SA 4.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File: From_the_holy_land_ Juresalem_ in_Palestine_Al-Aqsa_Mosque_-_Dome_of_the_Rock_From_inside.jpg

7. Photo by Berthold Werner, CC BY 3.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kairo_Ibn_Tulun_Moschee_BW_5.jpg

8. Photo by LeCaire, Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ibn_tulun_wall.jpg

9. Photo by Berthold Werner, CC BY 3.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kairo_Ibn_Tulun_Moschee_BW_7.jpg

10. Photo by Berthold Werner, CC BY 3.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kairo_Ibn_Tulun_Moschee_BW_6.jpg

11. Photo by Djehouty, CC BY-SA 4.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ibn-Tulun-Moschee_2015-11-14k.jpg

12. Photo by Baldiri, CC BY-SA 3.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ibn_Tulun_5.jpg

13. Photo by Faqscl, CC BY-SA 4.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ceramic_large_bowl_-_13th_century_-_probably_Gorgan_-_inventory_number_146_-_Abgineh_Museum_of_Tehran.JPG

14. Photo by Faqscl, CC BY-SA 4.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ceramic_bowl_-_9-10th_century_-_unknown_place_-_inventory_number_471_-_Abgineh_Museum_of_Tehran.JPG

15. Photo by Faqscl, CC BY-SA 4.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ariana_museum_-islamic_pottery_-_Bol_-_Irak_probablement_Basra_-_IX_i%C3%A8me_si%C3%A8cle_-_inventaire_AR_12746.JPG

16. Photo by Jastrow, Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dish_epigraphic_Louvre_AA96.jpg

17. Walters Art Museum, Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Iranian_-_Islamic_Wall_Tile_-_Walters_481281_(2).jpg

18. Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bowl_LACMA_M.73.5.133.jpg

19. http://persian-book.wikidot.com/

20. Photo by Otavio 1981. Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:A_treatise_on_chess_2.jpg

21. Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bagdad1258.jpg

22. Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File: Mohammed_receiving_ revelation_from_ the_angel_ Gabriel.jpg

23. Public domain. Scanned image from the book “A Collectors’s Fortune: Islamic art from the collection of Edmund de Unger”, 2007. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Keir-Koran-1300.jpeg

24. Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Panel_containing_excerpt_from_Quran_chapter_56.png

25. Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:AndalusQuran12th-cent.jpg