8.3 Witness for Idealism

Sant’ Apollinare Nuovo

“Oh, when the saints go marching in!”2 Women on the left, men on the right—still marching, processing in identical rhythm to the colonnades on either side of the nave at the basilica of Sant’ Apollinare Nuovo [image 8.29]. These lovely mosaics, in which virgins and monks are given equal status and elaborate costuming, stride idealistically over religious and political conflicts as well as significant damage from earthquakes and geological subsidence, pirates and war.

This lovely basilica had been built during the reign of the Ostrogothic king Theodoric (r. 493-526) when the sedes imperialis (Imperial seat) of the Western Roman Empire was in Ravenna and Arianism was the official court religion. Arians rejected the Orthodox doctrine of the consubstantiality of God the Father and Christ the Son. In their monotheistic belief, Christ had been created by God and was therefore subordinate to the Father; he was not “of the same substance” as Orthodox Christians professed. Built around the same time as the Arian Baptistery,3 the church had been dedicated matter- of-factly to Christ the Redeemer. The royal palace of the king was located directly to the south of the basilica and it was possible that a door led directly from the palace grounds into the southern aisle of the church.

We do not know what the Arian artists placed on the walls of the nave, but Theodoric died in 526 and in 540 Ravenna was defeated by the Byzantine armies of Belisarius. Arian decoration was surely considered offensive to Orthodox authorities and needed to be “taken care of.” In the “reconciliation” to Orthodox theology images containing a Trinitarian emphasis were placed in numerous locations and a procession of martyrs was tiled to accentuate the long nave.

Constantine’s legalization of Christianity in 313, as well as his fascination with relics, had lead to a new devotion to the possibly 100,000 martyrs who had suffered imprisonments, beatings or death rather than abandon the faith. The extended area of the frieze was the appropriate place to celebrate those whose sacrifice had unified and strengthened the church.

St. Apollinare was one of those martyrs. As the first bishop of Ravenna, he was believed to have been sent by St. Peter as a missionary to Ravenna where he worked for nearly 20 years before being lapidated (stoned to death) by pagans or teenage hoodlums, ca. 75 CE. In an alternative version of his story, having the audacity to convert people and perform miracles, Apollinare was brought before a Roman judge, tortured and martyred about 180 CE. He was buried in a cemetery in Classe, which was the port city 8 km outside the city gates of Ravenna.4

The Arian basilica had long been praised for its gilded beams and coffers which reminded the populace of a Coelum aureum (Golden Heaven), and, indeed, they occasionally referred to the church by that glowing expression. In the 561 Orthodox reconsecration of the church under the Emperor Justinian, the gilded ceiling suggested a renaming of the facility to Sanctus Martinus in Coelo Aureo (St. Martin in Golden Heaven). Originally the sanctuary (including the apse and triumphal arch)5 would have been the liturgical focus. It is believed that mosaics on the sanctuary walls would have complimented the golden heavens but an earthquake sometime between 726 and 744 (during the reign of Archbishop John V) destroyed the entire eastern end.

Whatever “truth” there is to the story of St. Apollinare, his prestige in the Emilia-Romagna region was huge. Several communities of faith were influenced by him so in 856 when his remains were transferred from their previous location at the Basilica of Sant’ Apollinare in Classe to a “safer” location inside Ravenna’s walls and away from Arab pirates the basilica was rededicated again as Sant’ Apollinare Nuovo (New Church of St. Apollinare) –“new” in that it was newer than the other churches around Ravenna with similar names. This specific “New” basilica is actually older than the one now known as Sant’ Apollinare in Classe.

In the sixteenth century land subsidence, common to all structures in the shallow coastal aquifer of the Ravenna coast, had become so severe that the original floor was 1.25 to 1.5 meters (4 – 4 ½ feet) below today’s floor. At that time the entire colonnade (including the arches), mosaics and floor were raised by the removal of a horizontal band (possibly stucco) between the arcade and the current mosaic frieze of processing saints. A new elongated Baroque sanctuary as well as a new marble portico was added during that renovation.

Adding to the insults on this precious basilica, bomb damage during the first World War destroyed that sanctuary. The current sanctuary dates from 1996.

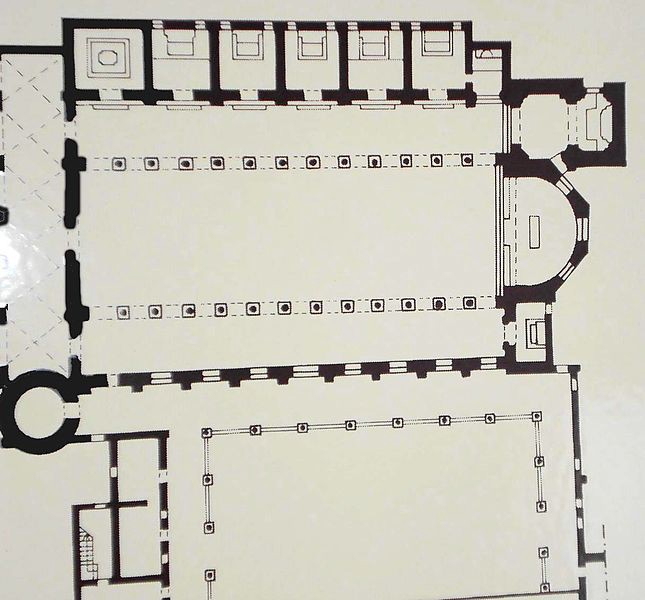

Stylistically, the traditional basilica church was similar in plan to Old St. Peter’s Basilica and St. Paul’s Outside the Walls, both in Rome.6 The façade was probably enclosed by a quadraporticus in front. Though smaller than Constantine’s Throne Room (Aula Palatina) in Trier, the interior proportions of 138’ long by 69’ wide were also equally correct according to Pythagorean (Greek) logic: a perfect 2:1 ratio. The ninth to tenth century campanile (belltower) has more windows at the top to make it look more slender, taller, more graceful, and to reduce the weight of the structure.

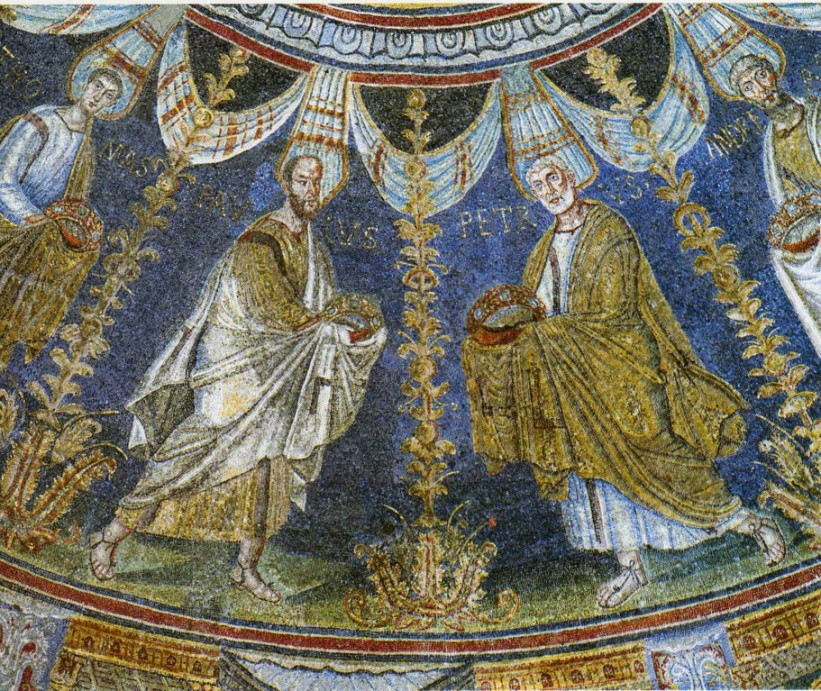

In the nave as seen today, our attention is drawn first to the more dignified (and warmer) south side where a heavenly court of 26 male martyrs is moving east toward Christ and his angels [image 8.32]. Washed of all sins, the saints are wearing their chaste robes of innocence and carrying their crowns of victory over death. We are unsure about the significance of the gammadia (hierograms of Greek writing) on their mantles.9 Slight variations in each saint’s hair color, facial hair, head tilt and crown decoration give us little clues to their identity; we are grateful to have them designated by the names printed above each head.

Leading the procession is Saint Martin of Tours who died in 397 [see also image 8.33]. A Roman soldier, he was remembered for his Christian compassion when he shared his cloak with a beggar. He later left the Roman army because he considered serving in the military to be incompatible with his Christian beliefs and in the 370s he became bishop of Tours in Francia. The renaming of the church in his honor (St. Martin in Golden Heaven) was both a compliment to his fierce opposition to Arianism and a political statement aligning the Byzantines and the Franks in the face of Lombard threats. The artist has honored Martin, who was not a martyr, with a new, royally influenced, purple mantle. St. Martin is followed in the procession by two popes, Saint Clement (88-99) and Saint Sixtus II (257-258). In mystically significant number four position is the man who served Pope Sixtus II so loyally, St. Laurence.11 He is distinguished by his golden tunic under a white mantle. The theologian Hippolytus comes next, followed by another man who was also a pope, Saint Cornelius (251-253). Cornelius is holding his crown with just one hand and is pointing his right hand toward the man behind him, Cyprianus of Carthage, who was a friend and ally during a different schism between the Orthodox Christians and another heretical sect. Included later in the procession are saints who had a close connection to Ravenna: Vitalis (11th in the line), his sons Gervasius and Protasius (12th and 13th in line), and Apollinare (17th in the line). Most importantly, both the monks and the virgins on the opposite wall are witnesses in an eternal procession which is moving forward into the heavenly presence of God.

Compare the dignity of these saints [image 8.33] to the peasants illustrated on the Arch of Constantine [image 8.34]. Both display the Classical Greek characteristic of isocephaly in that their heads are on the same level. These are both are idealistic representations. Balance and order are important; individualism is not. Within each composition, the poses, expressions and dress of the figures are similar.

The contrasting treatment of the art element of space in these two examples is significant. The martyrs are tall and elegant; the peasants are stubby. The saints are icon-like, frontal, and eternal. The processing men are presented in closed space: they are neatly placed in almost rectangular frames without overlapping or depth. The commoners, on the other hand, do show some overlap and three-dimensional space.

A comparison of the martyrs’ procession with the earlier sequence of the disciples on the dome of the Orthodox Baptistery [image 8.35] depicts a widely different treatment of light. The disciples exhibit dramatic shading in their clothing and they cast dark shadows as they stride forth on firm, green ground. This brings a naturalistic reality to their existence which is complimented by the starry firmament glittering behind them. The martyrs [image 8.36], on the other hand, are not depicted in natural light; instead, they are set against an otherworldly and heavenly gold background. The martyrs are portrayed in undefiled, pure color. The primary colors of blue, red and yellow are eternal colors; all other colors are derived from these. According to Platonic philosophy, shading or blurring of color would have suggested the corporeal matter of this lower world which is focused on mortal, fleshy and temporal things. Complimenting the mystical presentation, the feet of the martyrs are surrounded by an aureole of light made by bright yellow tesserae. Serving as a connection between Heaven and Earth, they radiated the light of Christ from within. The sixth century theologian and neo-Platonic philosopher Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite stated, “While man is a spirit imprisoned in an earthly body, a saint is more spiritual in form.” Here the artists have willfully inverted the natural order of optical experience. They are denying this transient world.

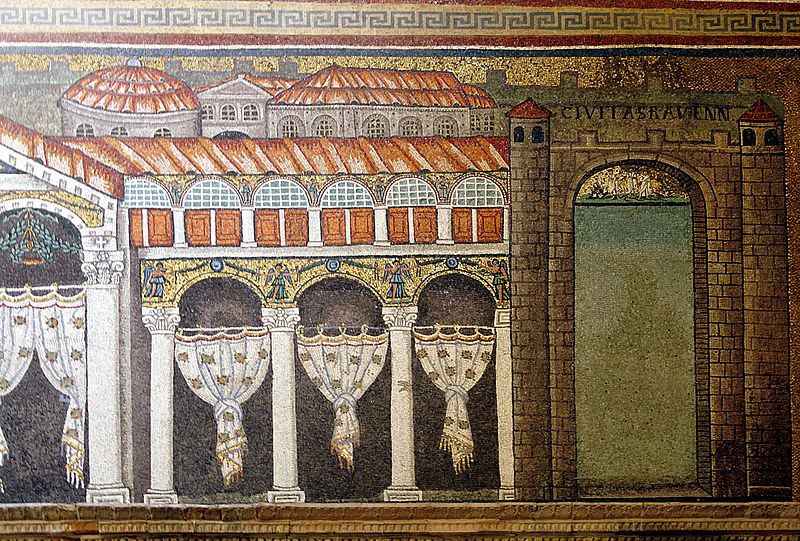

Look again at the entire length of the south wall [image 8.37]. The Orthodox-professing saints are processing from the Arian King Theodoric’s palace, which is labeled PALATIVM [image 8.38], toward the Throne of God. Behind the palace walls are possibly some buildings from sixth century Ravenna, or this may be a suggestion of heavenly Jerusalem, or these may just be “buildings.” In a didactic manner, however, the Byzantine artists turned this from a “cityscape” into a “teachable moment.” What is with those random fingers, hands and parts of arms on the columns of the Palatium? And what is the doorway on the far right side?

It is possible that the floating fingers, hands and parts of arms [images 8.38 and 8.39] were part of a mosaic which was unfinished at the time of Theodoric’s death. The more accepted speculation is that these are the remnants from the original Ostrogothic scene of the palace which included the king, his family, courtiers and Arian priests. Quite likely the Eastern Roman armies, upon conquering the heretics, lost no time in renaming the church and obliterating the face and form of Theodoric wherever they could. In a radical renovation, seated heretical figures within the luxurious Palatium were removed, tessera by tessera, and the space filled with mosaic curtains. Those who had been standing with their hands raised in gestures of acclamation, or in orant positions of prayer, have been allowed to remain, in a gesture of “Damnatio Memoriae”—“don’t forget to remember.”

Perhaps the authorities were not determined to erase a figure from memory, but to remind the viewer that the figure had been erased.

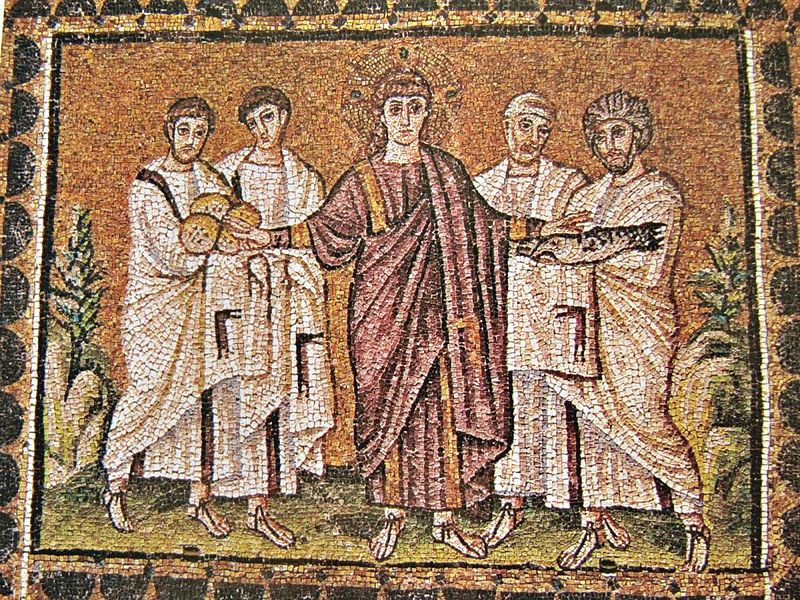

At the far right of the mosaic of the palace is a lunette over a doorway which gave another warning to heretics [images 8.40 and 8.41]. The door possibly led to the church of St. Laurence (aka Mausoleum of Galla Placidia).19 It is usually asserted that the lunette depicts Christ standing between two apostles. He holds a cross over one shoulder and a book in his other hand while he tramples on the evil of this world. This image sends one of two messages. If the lunette had originally been in the central arch of the Palatium pediment (now empty), then Christ was stomping on Satan. If it had originally been made for this location, then he was stomping out indigenous religion, i.e. the Arians. With either placement, Christ was defending his church.

A similar image from the century older Chapel of Saint Andrew in Ravenna expressed the message of a warrior like Christ more bluntly. This is known as a “Militans” and is possibly the earliest known image of this subject [image 8.42]. Here a youthful Christ is dressed as a Roman soldier with a shining halo around his head, a purple robe over his shoulders, the cross in one hand and a book open to showing the text of John 14.6: “I am the way, and the truth, and the life.” The iconography derives from Psalm 91:13 “the young lion and the dragon shalt thou trample under feet” (KJV). The verse was part of the daily monastic service of compine (final prayers at the end of the day), and also sung in the Roman liturgy for Good Friday, the day of Christ’s Crucifixion.

Recapping the lineup: along the south wall of the Basilica of Sant’ Apollinare Nuovo the men are processing from our right to the left, from the earthly palace of the King Theodoric toward the gem-studded Throne of God which is near the apse [image 8.43]. Christ awaits them on a lyre-backed throne [image 8.44]. With his right hand he is making the gesture of an orator. Prior to the 1852 restoration/renovation by Felice Kibel he held an open book, on which was originally written “Ego sum Rex Gloriae” (“I am the King of Glory”). Today we see the pointed scepter which Kibel placed in his hands. Christ is wearing an imperial purple tunic and mantle with gold clavus and he is crowned with a gemmed halo. This could have been an interpretation of Matthew 25:31, “When the Son of man shall come in his glory, and all the holy angels with him, then shall he sit upon the throne of his glory” (KJV).

The men having been given careful instruction, a similar intentional correction to heretical thought was provided for women on the “less prestigious” north side. At equal elevation to the men, 22 virgins are processing from our left to the right, from the Port of Classe toward the Theotokos (the Mother of God) and Christ who are seated near the apse [image 8.45].

The round hulled ships, depicted on the left in image 8.46, are merchant vessels in the commercial port city. Again, we don’t know if the buildings of Classe shown behind the walls represent extant buildings or if they, like those depicted behind the Palatium, were included simply for artistic purposes. Neither do we know about the original Arian decorating program of the basilica, but it now appears that the ladies are intentionally leaving behind the luxury of trade, material goods and the walled town as they process towards the Mother of God.

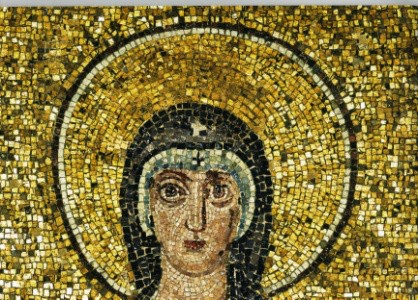

The processing women [images 8.47 and 8.48] look similar to the processing men. Cleansed of all sin, their presentation is also idealistic. They are all the same height, displaying the Classical Greek characteristic of isocephaly. Like the men, they carry their crowns of victory over death. Their poses, expressions, hair style, head tilt and expressions have the similarity of familial sisters with a little variation allowed for each woman’s shimmering silk and jeweled mantle. Again, they are presented in the closed space of nearly individual rectangular frames. They are icon-like with their eternal, frontal position. Unlike the men, they have no gammadia (hierograms of Greek writing) on their mantles, so we are really grateful to have them identified by the names written over their heads. The only woman who stands out is Saint Agnes, who has a lamb at her feet. Although the name ‘Agnes’ actually means ‘pure’ in Greek, it was quickly associated with the Latin word agnus, meaning ‘lamb’, and Saint Agnes is usually depicted with a lamb in Christian art.

We can be certain about whom they are going to see [image 8.49]. The 431 Council of Ephesus had clarified the concept of “Theotokos” as “Mother of God.” But in Greek the word literally means “bearer of God” and some heretical groups argued to address her as “God bearer” ranked her as a goddess, a concept used by heathens. By placing her in such an elevated position within this church, Orthodox authorities seemed to declaring, “Never you mind. Here she will be honored.”

And who will lead the women? Three Magi, of course [images 8.51 and 8.52]. Wearing colorful eastern robes with leopard-spotted trousers (tights?) and Phrygian caps they look quite different from the women. They are not carrying crowns, but are presumably holding gifts. In the upper right hand corner (above Caspar) the Star of Bethlehem may be seen. The Persian caps replaced crowns in the 1852 reworking of the scene by Felice Kibel. But still, you may be asking, “Why Persian?” The correct answer was, “Wisdom comes from the East—and Constantinople is to the east!” Everyone, from the East as well as from the West, was expected to prostrate themselves in the presence of the Trinitarian God.

We do not know what decoration was on either the lower or middle zone during King Theodoric’s time. There may or may not have been Magi. But, in any case, why did the Orthodox authorities depict three? Not only were three gifts mentioned in the Bible (gold, frankincense and myrrh), but three brings emphasis to the Holy Trinity and was, thus, an anti- Arian statement.

Just as we are able to scan our view from one end to the other, so the sun processes across the frieze [image 8.53]. Tesserae are not industrially flat, square or set on a planed surface. Tessera means “four corners” in Greek. The cubes could be hand-cut from stone, mother-of-pearl, gold, silver, or colored glass with 24k gold leaf sandwiched in between the layers. The tesserae were sometimes intentionally, and often unintentionally, set at dissimilar inclinations so they would reflect light differently as the illumination passes over the undulating surface. Light may be reflected off of a tesserae, giving the impression that each tile is emitting light, or the light may bounce from one point to another. When the sun moves, the figures on the wall appear to be in movement!

The walls of the nave were divided into three horizontal zones. We have been examining the processions of virgins and martyrs in the lower zone which were of newer, Byzantine influence.

The middle zone, between the windows, is also of Byzantine influence [image 8.55]. In total thirty-two men are depicted, each holding an open or closed scroll or codex (book). None of them is identified, and they do not seem to represent specific persons, unlike the male and female saints just beneath them. The men have been interpreted as prophets, evangelists, patriarchs, biblical authors or members of the heavenly court surrounding the Christ and the Madonna below them.

The mosaics in the upper zone depict the Roman sense of physical presence. The narrative movement depicted in these scenes at the very top of the wall is more similar to the lunettes at the Mausoleum of Galla Placidia and to even older scenes on Trajan’s Column. They provide a good contrast with the less than half-a-century newer static, devotional and ritualistic Byzantine mosaics. Whereas the more modern processional frieze and middle zones are each 10’ high (three meters), the upper zone, so far away and so small, is only 45” (1.15 meters) high. This Christological Cycle from the original Arian attic zone displays 26 scenes from the life of Jesus. Presumably these were non-offensive to Orthodox tradition and were allowed to remain, or perhaps they were just too high to be a bother.

These scenes are the earliest surviving long cycle of Gospel scenes in monumental art. Thirteen scenes from Jesus’ ministry are on the north wall; thirteen scenes from his last week on earth (the Passion) are on the south wall. Two examples will be examined. Look for the difference between the differing depictions of Jesus.

The mosaic of the Distribution of the Loaves and Fishes [images 8.55 and 8.56] is directly above the first window west of the apse (on the far east end of the north wall). As one faces the altar, it is on the viewer’s left side, placed with other miracle events close to the sanctuary where the Eucharist and miracle of Transubstantiation36 were celebrated.

The miracle depicted in image 8.57 was recounted in all four Gospel books (Matthew 14:15-21, Mark 6:38, Luke 9:13 and John 6:9). The event as told in the book of Matthew is similar to the others:

And when it was evening, his disciples came to him, saying, this is a desert place, and the time is now past; send the multitude away, that they may go into the villages, and buy themselves victuals. But Jesus said unto them, They need not depart; give ye them to eat. And they say unto him, We have here but five loaves, and two fishes. He said, Bring them hither to me. And he commanded the multitude to sit down on the grass, and took the five loaves, and the two fishes, and looking up to heaven, he blessed, and brake, and gave the loaves to his disciples, and the disciples to the multitude. And they did all eat, and were filled: and they took up of the fragments that remained twelve baskets full. And they that had eaten were about five thousand men, beside women and children (KJV).39

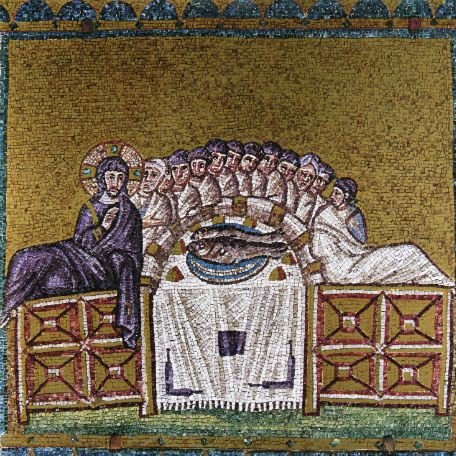

Looking to the viewer’s right on the south wall, the mosaic of the Last Supper was also placed at the front, and also near where the Eucharist was celebrated. It is the second scene in from the apse in the attic zone [images 8.58 and 8.59]. The event at the table is “read” from left to right. Jesus, on the left, may be identified by his jeweled Greek cross within a nimbus (halo), his purple tunic and mantle, and his hand raised in a gesture of peace. The artist, with the skillful use of tesserae, depicted tense and unhappy Judas on the far right. Could that many bodies really fit into the allotted space? Do the disciples have corporeal bodies, or was this a mystical scene?

How is Jesus depicted differently in these last two scenes? Why might he be beardless in one and have a beard in the other?

The answer is an ongoing argument. Some authorities suggest that the “beardless” portrayal suggests Jesus’ human nature and his wonder-working Son of Man qualities. They contend that the “bearded” depiction indicates his more mature, divine nature as the glorified Son of God. Other scholars have suggested that these mosaics were just the products of two different workshops.

Historically, Egyptian pharaohs had a “beard of authority” that could be worn for ceremonial occasions. Greek philosophers, poets and statesmen wore beards. Roman emperors had been clean-shaven until Hadrian (r. 117-138), who wore a beard to display his admiration of Greek culture. St. Augustine of Hippo (354-430) stated, “The beard signifies the courageous man, the beard distinguishes the grown man, the earnest, the active, the vigorous.”42 In Eastern tradition, from the seventh century onward, shaving will be considered a vulgar, Western/heathen practice.

Most of the attention in this lesson has been on the martyrs. The martyr was a new kind of hero. He, or she, was the contemporary equivalent to an Archaic Greek kouros, or a kore: one who was triumphant, balanced and confident [image 8.61]. The martyr gives no indication of emotion or strenuous activity. Like the Jewish male lamb presented at Yom Kippur, the kouros was an exemplar of physical and moral perfection.

Portrayals of kouroi, saints and others in the heavenly court were an opportunity to give the individual kleos.43 The fame and glory of kleos was earned through nobility of character, courage and self-sacrifice. Kleos is a trait that belongs to only humans; gods cannot demonstrate altruism because they have nothing to lose. By definition, gods don’t die. The intention of these images was not to make an individual portrait but to call attention to the heroic excellence of their witness. Like the kouros, saintly glory could be gained through the unwavering witness of one’s faith.

There are a number of, often conflicting, stories about each of the martyrs but the meaning of “martyr” needs to be kept in mind. “Martyr” means “to witness.” It does not mean “to die.” Christian martyrs were the victims of imperial persecution. By forcing the authorities to put them to death they laid bare for all to see the intrinsic violence of the so- called Pax Romana. Their imitation of Christ, even to the point of death, brought Christ to the present.

To the Greeks, nudity had the connotation of heroic excellence. Earthly beauty was a metaphor for abstract beauty, for spiritual understanding, for intellectual harmony. Byzantine Christians shared the Greek understanding of heroic excellence, spiritual understanding and beauty, filtered through Plato and the neo-Platonists. As we saw at the Mausoleum of Galla Placidia, beauty is not to be found in this physical world. Lift your eyes: look to the higher symbolic world, the world of the heavens. But, the Christians had a contrary attitude toward any “pagan” practices, and especially toward nudity.

Better, they reasoned, to suggest abstract beauty through symbols of heaven. If the the heavenly city of God was “all manner of precious stones: jasper, sapphire, chalcedony (agate), emerald, sardonyx (onyx), sardius (carnelian), chrysolite,beryl, topaz, chrysoprasus, jacinth and amethyst…and the street was of pure gold as it if were transparent glass” (Revelation 21:19-21, KJV) then heavenly beauty with gold and jewels was an ideal exemplar of beauty.

We first saw the heavenly glory of light that does not depict material form (i.e. dematerialized light) when we visited New Kingdom Egypt. Without the play of light and shadow, three-dimensional space was flattened. Isolated from the background, the processing saints at Sant’ Apollinare Nuovo were also silhouetted, this time in a technique known as fondo d’oro, which literally translated means “gold background.” That makes the project sound expensive, and it was! But the ones being honored were worth the high cost of the gold leaf infused tesserae. The contrast of gold and the jewels of heavenly beauty provided a mystical sparkle, suggesting the spiritual truth of the martyrs’ witness. As declared a writing credited to the Chapel of St. Andrew, “Oh the light is born here, or captured here, here it reigns free.” The saints are providing us with a glimpse of the perfection of heaven.

References:

1. Public domain at upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/f/f8/Ravenna_Basilica_of_Sant%27Apollinare_inside.jpg

2. This setting was probably not in anyone’s mind when the black spiritual was written, and then famously recorded by Louis Armstrong in 1938, but it so fits this locale. The hymn tune immediately comes to mind when the visitor witnesses the procession.

3. See Hartman, Kathleen J. “Chapter 8, Orthodoxy vs. Heresy: Orthodox and Arian Baptisteries in Ravenna.” Humanities: New Meaning from the Ancient World. Colorado Springs, CO: Pikes Peak Community College, 2020. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

4. See Hartman, Kathleen J. “Chapter 8, Spotlight on the World of the Spirit: Sant’ Apollinare in Classe.” Humanities: New Meaning from the Ancient World. Colorado Springs, CO: Pikes Peak Community College, 2020. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

5. In post-Reformation congregations, the entire church interior is called the sanctuary.

6. See Hartman, Kathleen J. “Chapter 7, Constantine’s Great Decisions.” Humanities: New Meaning from the Ancient World. Colorado Springs, CO: Pikes Peak Community College, 2020. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

7. Photo by the author, Kathleen J. Hartman, 2016. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

8. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:St_Apollinare_Nuovo_-_plan.jpg

9. Z (zoe) could mean “life.” N (nu) could suggest “Nazarene.” Because St. Augustine promotes the “four-squared stability of saint’s lives” Γ (gamma) might suggest the quality of a “cornerstone.”

10. Public domain at search.creativecommons.org/photos/65fe52e9-b2c8-49e7-a606-0046b7b438a6

11. See Hartman, Kathleen J. “Chapter 8, Development of Symbolic Art: Mausoleum of Galla Placidia.” Humanities: New Meaning from the Ancient World. Colorado Springs, CO: Pikes Peak Community College, 2020. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

12. Public domain at search.creativecommons.org/photos/f0521586-ec64-45c8-b07c-26a2b8f587e7

13. See Hartman, Kathleen J. “Constantine: Converting the Empire to Christianity. The Ambition of Constantine.” Humanities: New Meaning from the Ancient World. Colorado Springs, CO: Pikes Peak Community College, 2020. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

14. Photo by the author, Kathleen J. Hartman, 2016. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

15. Public domain at search.creativecommons.org/photos/f0521586-ec64-45c8-b07c-26a2b8f587e7

16. Public domain at search.creativecommons.org/photos/65fe52e9-b2c8-49e7-a606-0046b7b438a6

17. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Left_section_-_Theodoric%27s_Palace_-_Sant%27Apollinare_Nuovo_-_Ravenna_2016.jpg

18. Public domain at upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/d/df/Sant%27.Apollinare.Nuovo08.jpg

19. See Hartman, Kathleen J. “Chapter 8, Development of Symbolic Art: Mausoleum of Galla Placidia.” Humanities: New Meaning from the Ancient World. Colorado Springs, CO: Pikes Peak Community College, 2020. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

20. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Right_section_-_Theodoric%27s_Palace_-_Sant%27Apollinare_Nuovo_-_Ravenna_2016.jpg

21. Photo by the author, Kathleen J. Hartman, 2016. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

22. Public domain at upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/c/cc/Christ_treading_the_beasts_-_Chapel _of_Saint _Andrew_-_Ravenna_2016.jpg

23. Public domain at en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Basilica_of_Sant%27 Apollinare_Nuovo#/media/File: Sant_Apollinare_ Nuovo_ South_ Wall_Panorama.jpg

24. Shared under Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike license at christianiconography.info/Edited%20in%202013/Italy/sApolNuovoRightNave.christAngels.html

25. Public domain at en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Basilica_of_Sant%27Apollinare_ Nuovo#/media/File: Sant_Apollinare_ Nuovo_ North_ Wall_Panorama_01.jpg

26. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mosaic_of_the_Port_and_Town_of_Classe,_Basilica_of_Sant%27Apollinare_Nuovo,_Ravenna,_Italy_( 6124783623).jpg

27. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Sant%27Apollinare_Nuovo#/media/File:Ravenna-apollinarenuovo01.jpg

28. Public domain at search.creativecommons.org/photos/deda97a6-e2fb-47ac-92c2-b0bded4e39e5

29. Public domain at search.creativecommons.org/photos/8fff690a-147a-44ec-bf2e-c6757b6d4a24

30. Photo by the author, Kathleen J. Hartman, 2016. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

31. Public domain at search.creativecommons.org/photos/77e2e651-d0af-48c3-bd2d-081eab6690da

32. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ravenna_Basilica_of_Sant%27Apollinare_Nuovo_3_Wise_men.jpg

33. Photo at Sant’ Apollinare Nuovo by Kristine Betts, 2019. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

34. Public domain at search.creativecommons.org/photos/77e2e651-d0af-48c3-bd2d-081eab6690da

35. Public domain at upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/f/fd/Ravenna%2C_ sant%27apollinare_nuovo%2C_ int.%2C_ storie_cristologiche%2C_epoca_di_teodorico_01.JPG

36. Transubstantiation is the belief that during Mass (a religious ceremony) what appears to be ordinary bread and wine are transformed into the body and blood of Jesus Christ.

37. Photo by the author, Kathleen J. Hartman, 2016. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

38. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Feeding_the_multitude,_Sant%27Apollinare_Nuovo,_Ravenna.jpg

39. In a related event, it will be claimed that Hagia Sophia in Constantinople has a casket with crumbs left from this feeding of the 5000. See Hartman, Kathleen J. “Chapter 8, The Junction of East and West: Hagia Sophia.” Humanities: New Meaning from the Ancient World. Colorado Springs, CO: Pikes Peak Community College, 2020. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

40. Public domain at upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/6/63/S._Apollinare_Nuovo_Last_Supper.jpg

41. Photo by the author, Kathleen J. Hartman, 2016. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

42. Augustine of Hippo, Exposition on Psalm 133, 6. Leviticus 19:27, Clement of Alexandria, and the Capuchin Friars had similar comments.

43. Kleos is related to the English word “to call,” as in “what others say about you.”

44. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Public domain at www.metmuseum.org/toah/works-of-art/32.11.1/

45. Public domain at search.creativecommons.org/photos/deda97a6-e2fb-47ac-92c2-b0bded4e39e5

46. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Meister_von_San_Apollinare_Nuovo_in_Ravenna_001.jpg