8.2 Development of Symbolic Art

The Mausoleum of Galla Placidia in Ravenna

“She was the real power behind the throne.” We’ve heard this before when we looked at the life of the Egyptian Queen Hatshepsut. In Ravenna, Galla Placidia also led an extremely colorful life, though she felt no need to dress in a manly manner or be addressed as “His” majesty. The daughter of Roman Emperor Theodosius, she was the half-sister of the Honorius Augustus (who had moved the Imperial residence of the Western Roman Empire from Milan to Ravenna in 404). While she was living in Rome in 410 the city was sacked by Alaric and the Visigoths. She was taken hostage and is said to have become an early example of what we now call the Stockholm syndrome: she fell in love with her barbarian kidnapper, Alaric’s successor, Athaulf. In 414 she married Athaulf and went into battle for his side. When Athaulf was assassinated, she was bought back by her half-brother, Honorius, with a payment of corn. In 416 she was forced to marry a Roman general named Constantius III, to whom she bore two children, Honoria and Valentinian. Through the complications of Roman politics, their son Valentinian III became emperor at age 6. You guessed it: she assumed the control of the empire, ruling in his stead as Galla Placidia Augusta from 425-437.

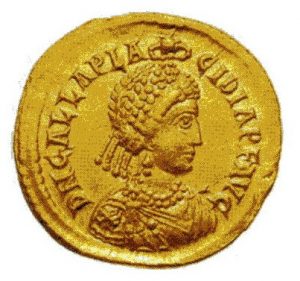

This 4.5 gram gold solidus is dated to 421-450 [image 8.17]. Throughout this chapter you will be studying symbols, and this is a good place to do some careful looking. Symbols are the language of religion while numbers are the language of science.

- Over her head, the hand of God holds either a crown, a nimbus (halo) or a wreath.

- On her head, a pearl diadem (a jeweled headband used as a royal crown) with four tails or her hair is adorned with jewels.

- On her neck, two pearl necklaces.

- On her ears, earrings.

- On her right shoulder, Chi-Rho monogram

(aka Cristogram).

(aka Cristogram). - Solidus of Galla Placidia Being Crowned by the Hand of God. 421-450, Altes Museum Berlin.

Galla Placidia2 was a devout Christian. She was involved in the building and restoration of over 100 churches where pagan temples had once stood in Ravenna and around the surrounding countryside. She has been credited with the restoration and expansion of the basilica of Saint Paul Outside the Walls3 and the Church of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem. She built San Giovanni Evangelista (St. John the Evangelist) in Ravenna in grateful appreciation for the sparing of her life and those of her children in a storm while crossing the Aegean Sea.4 The dedicatory inscription reads “Galla Placidia, along with her son Placidus Valentinian Augustus and her daughter Justa Grata Honoria Augusta, paid off their vow for their liberation from the danger of the sea.”

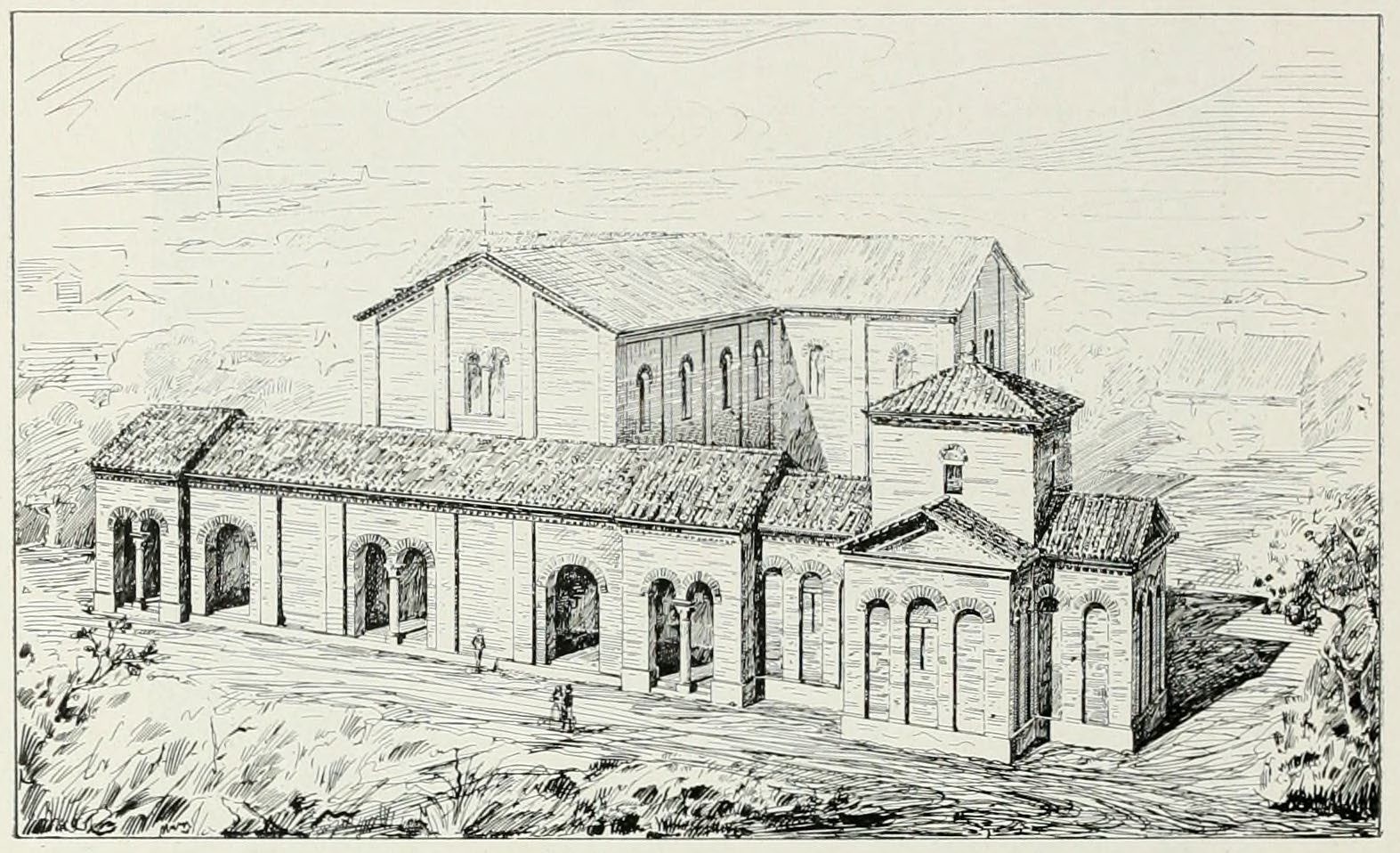

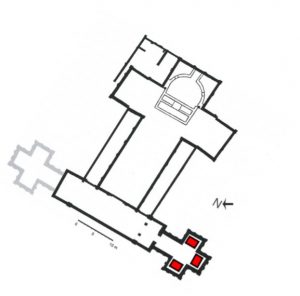

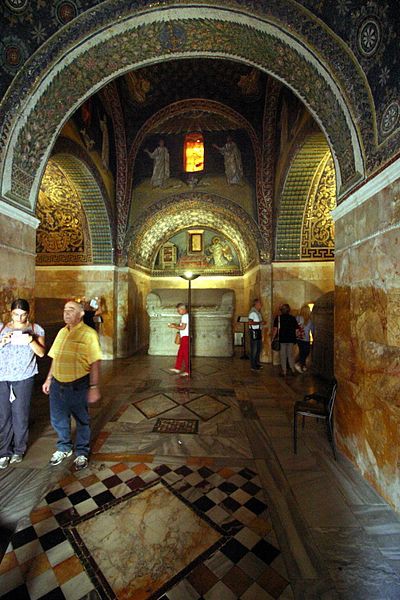

Her intended mausoleum was originally attached as a side chapel to the basilica of Santa Croce (Holy Cross) which she also built [images 8.18 and 8.19]. The cruciform shapes of the main body and side chapel were intentionally styled in remembrance of St. Helena who was by this time famous for her discovery of the True Cross.5 It has been speculated that Galla Placidia may, herself, have owned a relic of the True Cross.

Unfortunately for her story, she died in Rome, so it is unlikely she was buried in Ravenna. She was possibly buried in St. Peter’s Basilica, although a ninth century legend had her buried in a side chapel in San Vitale in Ravenna and another thirteenth century legend had her entombed in one of the sarcophagi here.

Constructed of reused Roman brick,9 the exterior of the Mausoleum of Galla Placidia is decorated only by blind arcades and looks rather bland [image 8.20]. Galla Placidia would possibly remind us, however, of the admonition spoken in the book of First Samuel 16:7: “The Lord sees not as man seeth; for man looketh on the outward appearance, but the Lord looketh on the heart” (KJV).

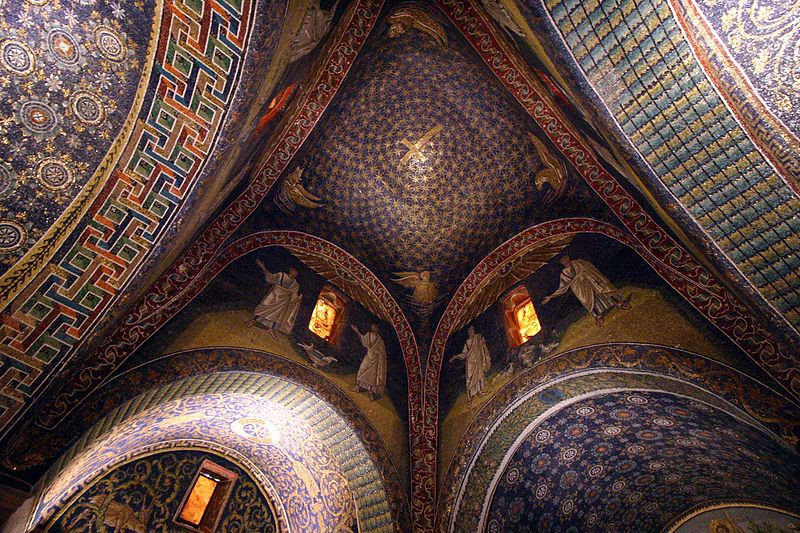

Inside we find the lantern tower has concealed a dome in which is displayed a supernatural world with glimmering mosaics [image 8.21]. The tesserae are made of glass with gold leaf sandwiched in between the layers. If the exterior represented St. Augustine’s Earthly City, the sparkle of the interior represents the Heavenly City.10

Come back down to earth. Look around us, at eye level [image 8.22]. We are seeing two zones: the lower one of marble panels and the upper one of mosaics. This is a visual distinction between the heavenly and the terrestrial worlds. Platonic thought is being mystically and symbolically suggested! The heavenly world is the realm of the spirit, of light, of invisible truth. The terrestrial world is the realm of the flesh, this visible world. We find ourselves in this world, but we can catch glimpses above of the truly “real” world, the world to which we would seek to ascend.

After one’s amazement at the heavenly splendor, the visitor comes to realize that there are stories all around us. These are not Roman stories of current events and real people, as we saw at the Ara Pacis or on Trajan’s Column, but mystical stories. Under the influence of Mysticism the stories are symbolic, expressing religious feelings rather than empirical people in the present world.

Looking horizontally ahead, the first lunette be seen by the visitor is the story of St. Laurence of Rome [images 8.23 and 8.24].13 According to tradition Laurence was called from Toledo in Spain to Rome by Pope Sixtus II in 257. After he arrived the Pope was summoned before the Roman authorities, who demanded that he turn over the treasures of the church. The Pope, of course, refused. As the Pope was being handed over for punishment, Laurence reportedly said, “Oh, my Father, I wish I could go with you.” The Pope replied, “Don’t worry, my son. Your turn will come.” Later Emperor Valerian’s henchmen approached Laurence, who replied that if they came the next day he would provide the “treasures” of the church. What were the “treasures” of the church? (Is Christianity even legal in 258 CE?) The “treasures” were the poor, the blind, the lame, the homeless, the widows. The authorities were not amused and declared that he would pay for his insolent humor by being grilled on a gridiron. On August 10, 258 he was martyred. Laurence was reported to have exclaimed, as the torture ensued, “Let my body be turned; one side is broiled enough. You may eat.”14

It’s quite a story, but what peasant can resist the account of a man who knowingly stood up to Roman authorities, who will gave his life, who promoted the dignity of being human? This mosaic, possibly the oldest to decorate a sacred space, depicts a gridiron, which could have held cooking pots, placed over coals. Laurence, wearing “discipleship” white, advances without hesitation toward the grill. His story will be retold in many locations, including on the Sistine Chapel ceiling painted by Michelangelo and in sculpture at Chartres Cathedral. You may easily recognize him because he often has a gridiron (which often looks like a ladder) either placed beside him or he is actually lying on the attribute.16 So influential was his story that our annual Perseid meteor shower was originally known as the “Tears of St. Lawrence.” As an aside, because of the bookcase, depicted on the left side of this lunette, Laurence is the patron saint of librarians. In the bookcase are the books of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John.

Is this Renaissance painting of “St. Laurence Distributing the Riches of the Church” [image 8.25] a fair interpretation of an event that happened 14 centuries earlier?

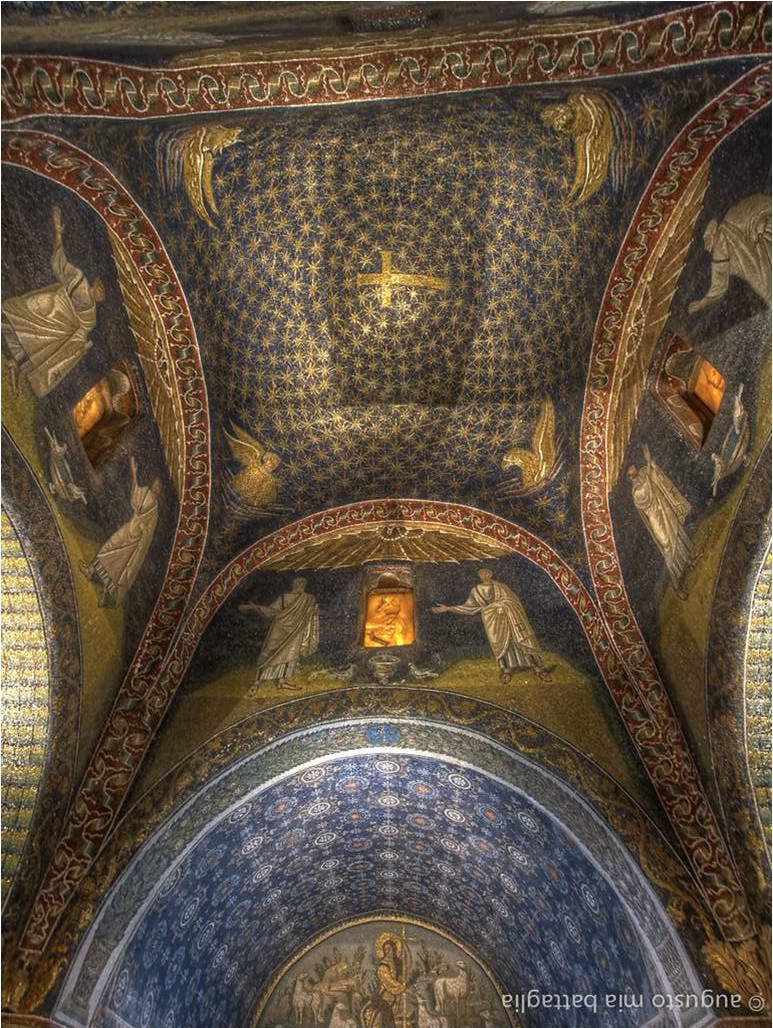

On the ground floor you were looking on a horizontal axis towards the lunettes; as you look into the dome you are looking on the vertical axis, ascending to the beauty of the heavenly world [image 8.26]. The dome still retains its original decorative program, with 8-pointed stars swirling in concentric circles around the symbol of ultimate sacrifice. Pendentives reach down like giant triangular vaults to make the transition from a square base to a circular dome. Like a renewed Garden of Eden, mosaics of running grape vines and Greek meanders link each of the barrel vaults of the cruciform plan.

Within the quadrangular lantern tower are visual reminders of the four Gospels, which coincidentally reach to the four corners of the earth. Clockwise from the top left:

-

A man (representing the book of Matthew, in which the genealogical record shows Jesus’ humanity)

-

An ox (representing the book of Luke, which describes the nativity and Jesus’ birth in a stable)

-

A lion (representing the book of Mark which promotes Jesus’ royal dignity)

-

An eagle (representing the more mystical book of John).

We were once facing St. Laurence, then with a 90o turn we saw the upright cross on the dome. In image 8.27 we have now turned once again to face the entrance door. How do you represent a god you have never seen? We have no likeness, no model, no description of what Christ looked like.

This is not an ordinary shepherd. What symbols are used in this Roman mosaic [image 8.28]?

- Christ does not hold a shepherd’s staff; instead, he is subordinate to the cross.

- He wears a imperial halo, a nimbus. (We will be seeing both the Emperor Justinian and the Empress Theodora wearing halos when we visit the Basilica of San Vitale in a later lesson.21)

- As the “light of the world,” the halo and Christ’s head fill the spot occupied by windows in the other three lunettes.

- He is youthful and without a beard, as we saw in the catacomb images.22

- He is wearing an expensive looking gold tunic with vertical clavi stripes, as were worn by the figures on the baptisteries in Ravenna23 and earlier on the Faiyum portraits from Egypt.24

- A pallium (Roman cloak) is draped over one shoulder and across his lap. Why is the pallium purple? Why was the clavi blue?

- He wears shoes! In the Greek theater gods could wear shoes; others went barefoot.25

References:

1. Public domain at upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/0/03/Galla_placidia%2C_solido_del_422.JPG

2. In Italian, “ci” and “ce” are pronounced like the “ce” in “cello.” Phonetically, her name is pronounced găl´ə pləsĬd´ēə.

3. See “Chapter 7, Constantine’s Great Decisions.” Humanities: New Meaning from the Ancient World. Colorado Springs, CO: Pikes Peak Community College, 2020. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

4. Destroyed in World War II bombing of 1944 but rebuilt according to the original design.

5. See Hartman, Kathleen J. “Chapter 7, Relics of Faith: Nicene Creed.” Humanities: New Meaning from the Ancient World. Colorado Springs, CO: Pikes Peak Community College, 2020. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

6. From Corrado Ricci: Ravenna. English version printed in Bergamo in 1913, page 58. Public domain at https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ricci_-_Ravenna_-_Santa_Croce_(reconstruction).png

7. Sign in front of the Mausoleum of Galla Placidia. Photo by the author, Kathleen J. Hartman, 2016. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

8. Public domain at search.creativecommons.org/photos/87e2545b-84d3-42ea-8084-4f0188a09c0c

9. Ravenna had been a municipium of the Roman Republic since 89 BCE. Caesar Augustus built a port facility in Ravenna that could hold, repair, and provision 250 ships. For the next 300 years Ravenna would be Rome’s main naval base for the eastern Mediterranean. There was plenty of used brick available.

10. The Khan Academy has produced a glittering video at the Mausoleum. https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/medieval- world/early-christian1/v/the-mausoleum-of-galla-placidia-ravenna

11. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Wide_angle_view_-_Mausoleum_of_Galla_Placidia Ravenna_2016.jpg

12. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Interior_-_Mausoleum_of_Galla_Placidia Ravenna_2016_(2).jpg

13. Other sources identify the saint in this lunette as the Spanish martyr Saint Vincent.

14. The Legend of St. Laurence is fully recounted in the Medieval Sourcebook: The Golden Legend: Volume IV. Sourcebooks.fordham.edu/basis/goldenlegend/GoldenLegend-Volume4.asp

15. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mosaik2_Mausoleum_Galla_Placidia.jpg

16. It is possible that this depiction inspired Dante’s Inferno. The poet lived his final years in Ravenna and died here in 1321.

17. Public domain at search.creativecommons.org/photos/f03814a4-287c-4be8-abd0-bbc48c222897

18. Photo by the author, Kathleen J. Hartman, at the St. Louis Art Museum, 2018. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

19. Public domain at search.creativecommons.org/photos/f2e9c168-b28c-4d6b-9677-ce4b2b6cf34f

20. Public domain at search.creativecommons.org/photos/baea8826-caf4-4334-9fd9-284b869e3fd6

21. See Hartman, Kathleen J. “Chapter 8, Justinian, Master of Three Powers: San Vitale.” Humanities: New Meaning from the Ancient World. Colorado Springs, CO: Pikes Peak Community College, 2020. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

22. See Hartman, Kathleen J. “Chapter 7, Christ as the Good Shepherd.” Humanities: New Meaning from the Ancient World. Colorado Springs, CO: Pikes Peak Community College, 2020. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

23. See Hartman, Kathleen J. “Chapter 8, Orthodoxy vs. Heresy: Orthodox and Arian Baptisteries at Ravenna.” Humanities: New Meaning from the Ancient World. Colorado Springs, CO: Pikes Peak Community College, 2020. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

24. See Hartman, Kathleen J. “Chapter 7, Anticipating Byzantine Culture.” Humanities: New Meaning from the Ancient World. Colorado Springs, CO: Pikes Peak Community College, 2020. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

25. See Hartman, Kathleen J. “Chapter 7, Relics of Faith.” Humanities: New Meaning from the Ancient World. Colorado Springs, CO: Pikes Peak Community College, 2020. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

26. Public domain at https://search.creativecommons.org/photos/4d20882b-a1ad-4186-96ec-d0ee4420388d