8.1 Orthodoxy vs. Heresy

The Orthodox and Arian Baptisteries in Ravenna

From reading the biblical New Testament account titled The Acts of the Apostles one gets the impression that Christianity moved uneventfully westward from Jerusalem to Rome. However, that action was not without controversy. In the first centuries after the death of Jesus there was little unity of belief and practice among many varieties of Christians. More correctly, there was bitter doctrinal controversy.

-

Was Jesus human or divine?

-

Did he suffer, bleed, and die? Was he resurrected?

-

What was the status of Jesus in relationship to God?

-

Did Jesus exist prior to his birth?

-

Was he born to a Virgin?

-

Which was more important: Jesus’ sayings or his death?

-

How did Christianity relate to Judaism?

-

Which literature was authentic? What should be done about forgeries?

-

What should be done about heretics?

-

Who was the authentic Pope, the successor to Saint Peter?

-

What should be the correct date for the celebration of Christ’s resurrection?

Each group of Christians was making its own apostolic link back to the teachings of Jesus. Each sect had its own canon and its own theological doctrine, and each thought they were being faithful in their understanding of Christianity.

Even the Christianity preached in Palestine differed from that of Rome. They were discussing far more gospels than the four that ended up in the New Testament. Persecution had magnified the acrimonious controversy and the theological differences. If Constantine, with the promotion of the Nicene Creed,2 expected Christians to unite behind him as a pious, harmonious people with a unified “One Way” belief he was disappointed.

As an essential component of his One Roman Empire objective, Constantine actively supported those who backed him with the building of a number of basilica churches, endowments to the church with land and other wealth, and scriptures copied at state expense. The beneficiaries of his largess were those who professed to the Orthodox3 tradition. Any one, or any group, that had unorthodox answers to the above doctrinal questions was labeled a heretic, and that meant willful opposition to the state. It is important to remember that at this time there was no separation between the church and the state. Heresy against the church was the equivalent to treason against the state. The philosophy for this position stemmed from teachings of Plato, who professed that “Truth must proceed before the corruption of truth.”4 In other words, Truth, as a Form of the Good (along with justice, equality, beauty), must outrank untruth. Plato taught that humans were compelled to pursue the superlative form of Truth; therefore, corruption of the truth (heresy) was an intentional, obstinate choice.

There were a number of variant understandings of the significance of Jesus—and therefore, a number of sects that were considered heretical. Unfortunately because their writings were intentionally destroyed in Diocletian’s burning of scriptures,5 we only know about these noncompliant Christians from Orthodox writings about the heretics. In spite of their widely divergent thinking, many of their answers toward the above questions flowed back to Rome, there to be purged of heretical views and later incorporated into Orthodox teachings. Among the contributions of deviant groups we know the word “Trinities” was first used in Tunis in the third century by the followers of Montanus. The term “Christian” was first coined in Antioch in Syria by the followers of Nestorius. The Docetist document, “The Gospel of Paul,” described Paul’s journey to the tenth heaven and also his view of the torments of the damned in hell. This was an influence on Dante’s Divine Comedy and perhaps also on the Islamic recounting of Muhammad’s ascent to the seventh heaven. The Docetists made early reference to the “harrowing of hell” (the time between Jesus’ death and resurrection when he descended into hell, preached, and offered salvation to the dead). And, it was the Docetists who intentionally shifted the blame for Jesus’ death away from the Roman governor Pontius Pilate and onto the Jews. The followers of Marcion of Sinope were also deeply anti-Semitic. Monophysite teachings are exemplified at several churches in Ravenna. At the Basilica of San Vitale paradise is served by four rivers of honey, milk, wine and oil. In the Basilica of Sant’ Apollinare Nuovo monks and virgins are given elaborate status. At the Basilica of Sant’ Apollinare in Classe the end times will be accomplished with a glorious vision of Christ in a lovely field of flowers, accompanied by Moses and Elijah. This basilica in Classe also revealed Platonically influenced Gnostic teachings: God was understood to be so spiritual and unitary that humans could never know him directly.

By the early fourth century most of these heresies—Montanists, Nestorians, Docetists, Marcionites, Monophysites, Gnostics and more—had been suppressed. Others heretics were almost ignored. But in the Western Roman Empire, the followers of the dissident Arian (c.250-336), a priest of the Church of Alexandria, Egypt were causing an unsightly raucous. Both the Orthodox and Arians accepted the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John, but the interpretations varied.

Arian’s challenges to Orthodox teachings had been set to noisy drinking and theatrical songs and soon even sailors were debating Jesus’ divinity. Not only was Arian deemed to be wrong in his understanding of the divine status of Jesus, but he was encouraging undignified, unRoman behavior. To conservative Roman citizens, without a doubt he must have been a heretic! His followers were severely denounced by the first Council of Nicaea, which wrote the Nicene Creed specifically to condemn his monotheistic heresy.

The difference between Orthodox teaching about the Trinity and the Arian understanding of Jesus is most easily understood by learning a bit of Greek! The Orthodox preaching was that Jesus and God were homoousios (of the same essence) and had existed since the beginning of time. Homoousios is the same word which in the Nicene Creed translates as “consubstantial with the Father.”6 Now, let’s split hairs, torment and even slaughter each other over a single vowel which has been omitted. The Arian teaching was that that Jesus was homousios (similar in essence but not the same). Arians taught that Jesus, as a human, grew and changed. He was, therefore, a subordinate being created by God the Father and there had been “a time when he was not.” Therefore, Jesus was not quite divine.

Got it? The difference was all over one “o”! Oh, and the Arian’s lack of respect for the authority of Rome and the primacy of the Orthodox Church (aka Nicene Christianity or Trinitarian Christianity). So was this an argument about a doctrinal controversy, or was it possibly a political power struggle?

Milan had served as the seat of the Western Roman Empire from 286 until 402 when the Visigoths besieged the city. Given the fear of further barbaric attacks the Emperor Honorius moved the Imperial residence to Ravenna. The coastal city had been built on marshy hinterlands so it was difficult to attack by land. Equally important, because of its location on the Adriatic Sea, it was convenient to Constantinople. While darkness overtook the rest of the Roman world, Ravenna was protected by this marshland and benefitted from the powerful nearby port of Classe, through which came Byzantine design, workmen and materials. Ravenna was the sedes imperialis of the Western Roman Empire from 402 until the Lombard invasion of 751. Subsidence and the rapid decline in population in the eighth century would result in a lack of both finances and the will to replace the early churches, for which we are rewarded with the neglected preservation of many dramatic and spectacular buildings, mosaics and carvings.7 In Ravenna we can get a sense of the richness of early Byzantine art that had once been empire-wide.

The controversy between Orthodox and Arian views was just one among many conflicts with heretical teachings, but it is visually well exemplified in two baptisteries in Ravenna, Italy. The intent of artistry in a baptistery was twofold: to decorate an exclusive place and also to teach and inform the participants about the only publicly celebrated religion in the Roman Empire. The essential components of this Christian rite of initiation were described in the synoptic gospels of Matthew, Mark and Luke. This citing is from the book of Mark, the first gospel to have been written:

Jesus … was baptized by John in [the] Jordan. And straightway coming up out of the water, he saw the heavens opened, and the Spirit like a dove descended upon him: And there came a voice from heaven, saying, ‘Thou art my beloved Son, in whom I am well pleased’ Mark 1:9-11 (KJV).

Christian theological concepts were still in a state of flux, but the sacramental procedure as established in the fourth century by St. Ambrose in Milan would spread throughout the west. The occasion was celebrated by immersion into a symbolically significant octagonal pool of water. Quoting from St. Ambrose, “Eight corners has its font, worthy of that number, it was suitable to build this hall for sacred baptism, because it corresponds to the Resurrection of Christ that took place on the eighth day.”8 Death, cleansing and resurrection were all commemorated in the immersion experience.

Our first destination in Ravenna is to the Orthodox Baptistery, the oldest of Ravenna’s ancient monuments [image 8.2]. It was built before 451 under the patronage of the Orthodox church. Being within the approved tradition you might expect that it has been well-maintained, and it has. The intentional separation of this structure from the nearby original fourth-fifth century Ursiana Cathedral drew focused attention to its octagonal exterior and gave an immediate clue that this was built for a ceremonial function. As a centrally planned building, the axis and the interior focus will be upward toward the glittery mosaics in the dome [image 8.3]

The modern word “ceiling” is derived from the Latin caelum which means heaven or sky. In images 8.3, 8.5 and 8.6 the viewer’s attention is drawn straight up into that sky, looking through the Greek egg-and-dart molding of the oculus and then gazing upon the golden, heavenly setting in which Christ is being baptized by John the Baptist.

The baptismal font [image 8.4] is directly beneath the heavenly vision, and when the baptizand (newly baptized) was lifted out of the waters he or she saw a vision of Christ experiencing the same ceremony [image 8.5]. The surrounding 12 disciples, who could each be identified by legible names printed in gold tesserae, were wearing their chaste robes of innocence, holding jeweled crowns of glory and processing in two lines behind the saints Peter and Paul. The disciples were veiled by a pallium (a drapery swag) which provides the illusion of a halo. The apostle Peter, leading one group, was placed in a position of dignity directly below Christ [image 8.6]. Leading the other group was Paul, who was placed directly beneath John the Baptist.

The Bishop’s church and baptistery were the prototypes, if not the “proper” settings for the sacred rites of the faith. But there were other voices wanting to be heard in Ravenna. The equally sincere followers of the Arian tradition demanded a new expression of their theological position. It is in the comparison of the two baptisteries, both in Ravenna, that we see the exemplification of two very different understandings of the significance of Jesus.

The Ostrogothic king Theodoric the Great (r. 493-526) became the ruler of most of Italy about 50 years after the construction of the Orthodox baptistery. Driven by antagonism to papal pressures and the economic convenience of the port at Classe Theodoric made Arianism the official court religion and built a new Arian church, the Basilica Spirito Santo,16 in a neighborhood separated from the Orthodox Christians. The Arian Baptistery [image 8.7] was included in the piazza in front of the church. Built about 50 years after the Orthodox Baptistery, it was similar in design but slightly smaller than the Orthodox Baptistery.

In an early church vs. state conflict, the funding for this church and baptistery was from royal, not ecclesiastic, sources. However, because of later condemnation of the Arian movement the structure has not had substantive capital or maintenance. The only mosaics to have been preserved are those of the dome, which were not considered offensive to Orthodox tastes; nothing is left of the decoration which once covered the walls [image 8.8]. In 565 the building was converted into an oratory, renamed Santa Maria in Cosmedin (Ornamented Chapel of Santa Maria), and sold to a private citizen. In 1914 ownership was transferred to the state.

The desire to compare the dome of the Orthodox Baptistery and the dome of the Arian Baptistery is hard to ignore. The iconography on the Orthodox Baptistery was reworked in 1860, while the original design of the Arian Baptistery is unchanged, so a comparison of these two is not being made on a level playing field. Pushing that hesitation aside, the astute observer will notice several deliberate choices made by the Arian artists.

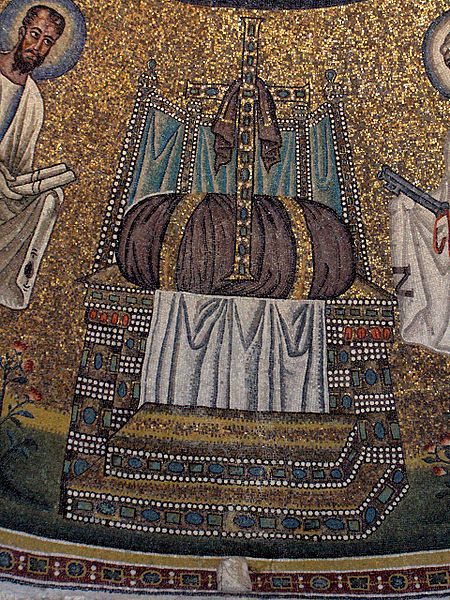

- The pallium (a drapery swag) linking the apostles has been replaced with distinct haloes.

- The apostles walk a narrow green line, separated from each other by stylized palm trees.

- The procession is more formal. There is a less movement, the heavenly gold background is timeless, and the apostles all wear white tunics with clavi (vertical stripe on the tunic) and mantles. Ten of the men hold their crowns of victory.

- In both examples the artists have depicted contrapposto movement and shadows beneath the disciples’ feet.

- What’s that thing at the top, upside down over the Dove [Image 8.9]? It’s a throne, prepared for the Second Coming.

- Etimasia (prepared throne) with a jeweled crucifix resting on a purple cushion.xviii

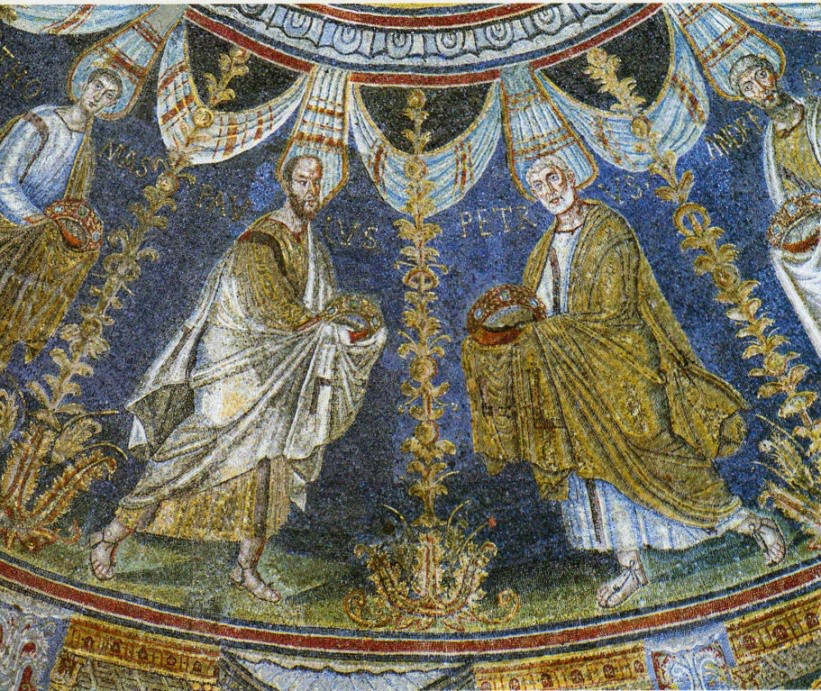

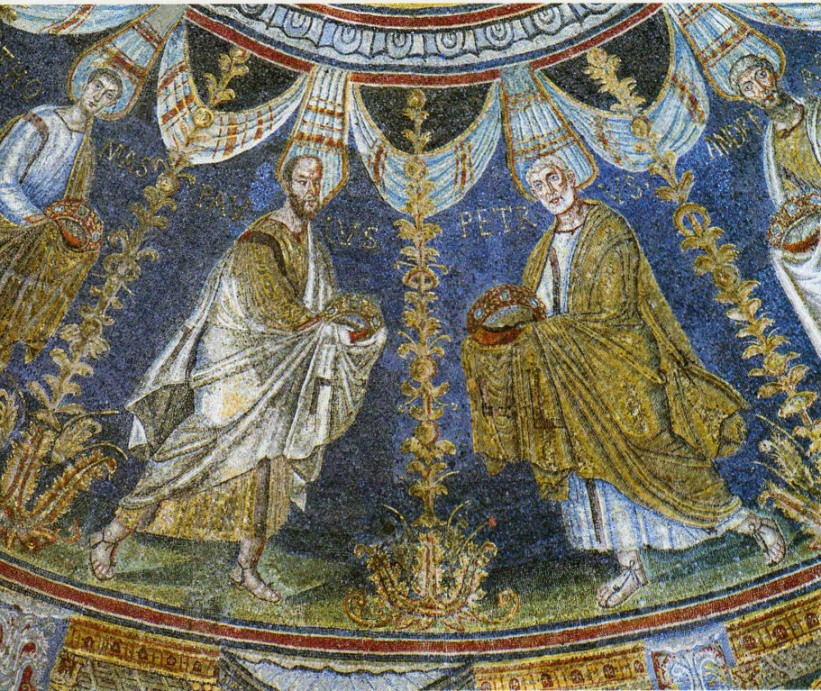

Paul and Peter face each other on both baptisteries and are quickly recognized. They are identified by name at the Orthodox Baptistery [image 8.10]. At the Arian Baptistery [image 8.11] their identity is known by their attributes. Peter, the “more mature” man with white curly hair, holds the keys to the kingdom. His halo is also white and he leads the procession with the first-called disciple, Andrew, directly behind him. The other nine around the dome have beige halos.

Paul, the younger man with an “intellectual” high forehead, holds a scroll at the Arian Baptistery, suggesting the numerous letters he wrote to Gentile converts. Significantly, his blue halo was repeated on the unnamed individual behind him. Perhaps the matching haloes suggest this to be Paul’s successor? But the tradition of Apostolic Succession originates from the line of Peter, not Paul. Was this possibly a hint that Paul’s successor was less clearly defined? That anyone, in any of Paul’s established congregations, could be a successor?

Consider the placement of Peter and Paul on the ceilings. At the Orthodox Baptistery [image 8.5] Peter is under the feet of Jesus, directly in a line of power and authority from Jesus (the line of Apostolic Succession) while Paul is honored for his evangelizing work by being placed under John the Baptist. At the Arian Baptistery [image 8.8], while Peter is given respect (after all, he does hold The Keys), he is out in “no man’s land.” Paul and “the other blue-haloed disciple” are more closely aligned with the independent spirit of John the Baptist.

Observe the ethnic diversity of the unnamed Arian apostles who circle the medallion [image 8.12]. Some sport beards, others are beardless, and at least one has “muttonchops” [image 8.13]. Was he, perhaps, a Goth?

In discussing the two dome medallions we must first note that at the Orthodox Baptistery [image 8.14] the heads of John and Christ, John’s hand, top of John’s staff and the dove were all restored and reworked in 1860 by Felice Kibel.

Over the centuries infant baptism had become more popular, as well as baptism by the sprinkling or pouring of water rather than immersion. Kibel placed a cup in John’s hand for the pouring of holy water and added a beard to Christ’s face.

There are many similarities between these two medallions [images 8.14 and 8.15]. Both give three-dimensional treatment to flora and figures and create illusionistic space. Both are set in a visionary realm; the floating, light-filled gold ground is a divine occasion, removed from space and time. Christ is depicted nude, without gestures of embarrassment. Both personify the River Jordan in the Roman style as an “Old Man River.” In both the Holy Spirit descends as a dove; this will lead to the common depiction of the Holy Spirit as a bird.

The obvious differences are significant. At the Orthodox Baptistery the medallion is set off with traditional Greek egg-and-dart molding; a more modern Roman wreath highlights the Arian medallion. In the Orthodox mosaic John the Baptist is on the viewer’s left; he is honored with a halo and holds a tall jeweled staff (which may have originally been a shepherd’s staff or crook). In the Arian mosaic John is on the viewer’s right. He is again bearded but he has no halo. John is not pouring water; with his right hand he is either making a sign of the cross or is resting his hand on Christ’s head. The River Jordan in the Orthodox Baptistery is personified as a man of wisdom preparing to pass a green mantle (cloth) to Christ. At the Arian Baptistery waters of the river pour from an upside-down amphora laid behind the river personification. The Holy Spirit is an active participant in the Arian scene; water flowing from the beak of the Holy Spirit may signify the giver of life, or the stream could be a beam of light.

The most significant difference is the intentional Arian formatting, both within the medallion and of the processional figures. In the Arian medallion [image 8.15] attention is drawn to Jesus with a framing of figures and gestures. Jesus is youthful and beardless in the style of the Early Christian images as seen in the catacombs.25 Dashed centering lines added by this author demonstrate the intentionality of the artist that Jesus occupy the central axis at the summit of the dome. As if to proclaim his much younger, very human nature, his navel is at the nexus of the dome. And the apostles, arranged as they are, give a higher status to Paul and the gentile converts and less to the organized, authoritarian, Orthodox church.

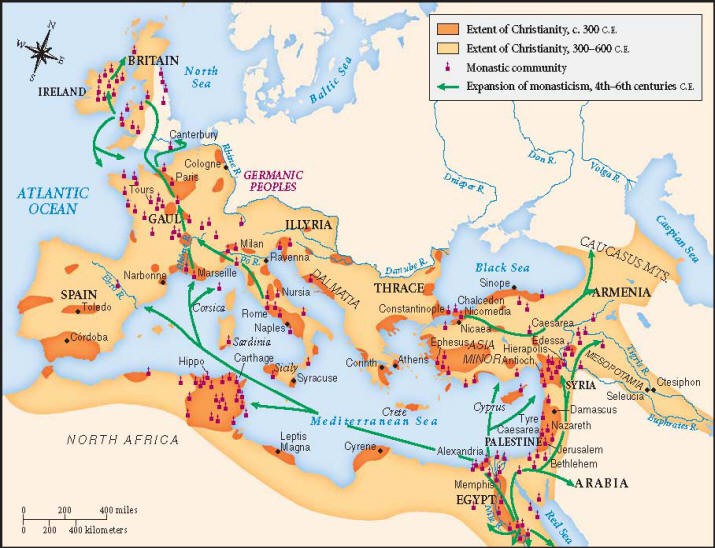

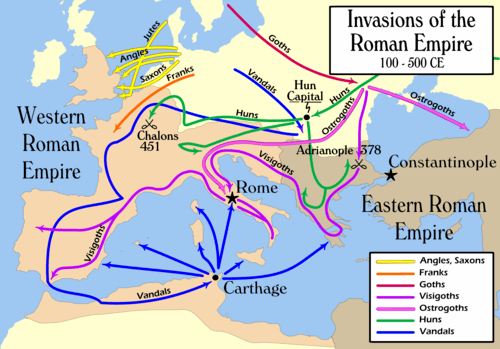

The differences at the two baptisteries speak to the power struggle that was going on between the One Way Orthodox teachings and the heretical Arian beliefs. St. Ambrose was quoted by St. Augustine as having remarked that the obstinacy of the Arians was “more detestable than that of the Jews.”27 Headstrong, they were! Arian thought was condemned by the Council of Nicaea in 325. In 381 their monotheistic teachings were again suppressed by the Council of Constantinople. But Arians continued to exist along the frontiers of the Roman Empire, especially in the Balkans and among Italian and Germanic peoples [image 8.16]. The Vandals of North Africa were militant Arians. Byzantine Emperor Justinian viewed them as pirates in the western Mediterranean and defeated them 532-534. The Ostrogoths, whom we have just met in Ravenna, were Arians. Although they blended with Roman society, they will be conquered by Justinian between 535 and 553. The Visigoths (western Goths) were also Arians. Weakened by the Franks (who may have been Arian), struggles against Justinian and political disunity, they were left in a debilitated state and fell to Muslim invaders from North Africa in 711-716. In a corrective course maneuver against all these #%!Goths&$, later Crusades became necessary.

Arian opposition to the dilution of the transcendent one, sole, only God by Trinitarian thought was also echoed by other heretical sects and by the teachings of Muhammad, which began in about 150 years.

References:

1. Public domain at https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Spread_christianity_between_300_and_600.jpg

2. See Hartman, Kathleen J. “Chapter 7, Relics of Faith: Nicene Creed.” Humanities: New Meaning from the Ancient World. Colorado Springs, CO: Pikes Peak Community College, 2020. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

3. Many of you have first-hand knowledge of an orthodontist. Ortho (straight) plus dentist (teeth.) Orthodox comes from the same root. Ortho (straight) plus dox (thinking). Therefore, unstraight thinking is heterodox, also known as heresy. A heretic, therefore, is one who chooses to think or believe differently.

5. See Hartman, Kathleen J. “Chapter 7, Brotherly Love in Turbulent Times.” Humanities: New Meaning from the Ancient World. Colorado Springs, CO: Pikes Peak Community College, 2020. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

6. See Hartman, Kathleen J. “Chapter 7, Relics of Faith.” Humanities: New Meaning from the Ancient World. Colorado Springs, CO: Pikes Peak Community College, 2020. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

7. “Guide to Byzantine Treasures,” at http://www.initaly.com/regions/byzant/byzant4.htm This is a really fine link that will get you up close and personal with the art of Ravenna.

8. Zeno of Verona, Tract, 1.49, 55.

9. Photo by the author, Kathleen J. Hartman, 2016. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

10. Ibid.

11. Ibid.

12. Ibid.

13. Ibid.

14. Ibid.

15. Public Domain at Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike license; upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/1/1a/Baptistery.Arians02.jpg

16. Built simultaneously with the Basilica of Sant’ Apollinare Nuovo.

17. Photo by the author, Kathleen J. Hartman, 2016. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

18. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Baptistery.Arians10.jpg

19. Photo by the author, Kathleen J. Hartman, 2016. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

20. Shared under Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike license at christianiconography.info/Edited%20in%202013 /Italy/ baptismJesusArianBaptistery.crossEnthroned.html

21. Public domain at https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Procession_of_the_Apostles._First_left Saint_Peter._Part _of _the_mosaic_in_Arian_Baptister y._Ravenna,_Italy.jpg

22. Deliyannis, Deborah Mauskopf. Ravenna in Late Antiquity. Cambridge: Cambridge U. P., 2010. Reproduced in color at corvinus.nl/2016/07/27/ravenna-the-arian-baptistery/

23. Photo by the author Kathleen J. Hartman, 2016. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

24. Ibid.

25. See Hartman, Kathleen J. “Chapter 7, Christ as the Good Shepherd.” Humanities: New Meaning from the Ancient World. Colorado Springs, CO: Pikes Peak Community College, 2020. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

26. MapMaster, “Invasions of the Roman Empire.” Ancient History Encyclopedia. Ancient History Encyclopedia, 16 Oct 2015. Web. 12 Oct 2019 on www.ancient.eu/image/4131/invasions-of-the-roman-empire/

27. Confessions of S. Augustine, IV.16.