7.8 Relics of Faith

The Nicene Creed

Before the days of the Emperor Constantine, the Roman government didn’t care about faith-based religion. Ritual was important; it was necessary to honor the gods who could assist and protect you, who could influence the outcome of any process that was risky, uncertain or incomprehensible. Proper performance was essential. With proper ritual the gods could grant health and prosperity. In contrast to pagan religions, Christianity was a religion of belief, not of cultic ritual. Its controlling principle, how to be right with God, was set with the belief in Jesus as God and in the sacrifice of his life.

While Constantine was a pragmatic politician, using whatever means available to achieve a stable empire, Jesus was non-political. As demonstrated in the Sermon on the Mount he was a pacifist and condemned worldly authority. But the Emperor ruled over an empire with a strong military tradition. Theologians had to rethink Christ’s previous and uncompromising hostility toward warfare of all sorts. If Christianity was going to work in a state ruled by a monarchy, it would have to change.

To solidify his power, in 325 Constantine called the First Ecumenical1 Council at Nicaea (near the Eastern Imperial residence at Nicomedia; modern Iznik, Turkey) to formalize Christian belief about the divinity of Jesus. Giving his active support to Trinitarian Christianity, the emperor covered all travel and accommodation expenses and presided over the Council. Foremost among the Council’s concerns were the heretical Arians, who were understood as “pagan” because they denied the divinity of Jesus and rejected the concept of the Trinity.

“Trinitarian Christianity” accentuated all possible opportunities to promote the three-part nature of God the Father, Jesus Christ the Son, and the Holy Spirit. Trinitarian practices were expressed in a standardized creed, authoritative scripture, and approved hymns, performed to a rhythm of “3.” Additionally, there were to be no more than three sacred languages (Greek, Latin and Hebrew).

Jesus’ Jewish heritage had established a precedent for both a creed and a sacred text. The Jewish “shema” was recognized as the fundamental expression of Jewish belief: “Hear, Israel, the Lord is our God, the Lord is One.” Jesus’ sacred text was the Torah, the law of God as revealed to Moses and recorded in the first five books of the Hebrew Scriptures (the Pentateuch). Had Jesus lived longer perhaps he, himself, would have been the authority, the scripture, but he didn’t write anything.

It was at this Council that the creed, to be known as the Nicene Creed was written. The statement, as used today2:

NICENE CREED, 325

I believe in one God the Father Almighty, maker of heaven and earth, and of all things visible and invisible.

I believe in one Lord Jesus Christ, the Only-Begotten Son of God, born of the Father before all ages, God from God, Light from Light, true God from true God, begotten not made, consubstantial with the Father, through him all things were made. For us men and for our salvation he came down from heaven, and by the Holy Spirit was incarnate of the Virgin Mary, and became man. For our sake he was crucified under Pontius Pilate, he suffered death and was buried, and rose again on the third day in accordance with the Scriptures. He ascended into heaven, and is seated at the right hand of the Father. He will come again in glory to judge the living and the dead and his kingdom will have no end.

I believe in the Holy Spirit, the Lord, the giver of Life, who proceeds from the Father and the Son, who with the Father and the Son is adored and glorified, who has spoken through the prophets.

I believe in one, holy, catholic and apostolic Church. I confess one Baptism for the forgiveness of sins and I look forward to the resurrection of the dead, and the life of the world to come.

Amen.

Notice that the Nicene Creed’s essential definition of the divine was in three parts: God the Father, Jesus Christ the Son and the Holy Spirit, which were unified into one statement of belief. The fourth section refers to the believer. The statement pledges commitment to additional miraculous phenomena, including:

- God and Jesus are “consubstantial” (made from one divine substance)

- Jesus was born of a virgin

- Jesus died, and rose from the dead (as had the heroes Osiris, Theseus, Herakles, Orpheus and Octavian)

- And the believer, too, will be resurrected

With this statement faith overshadowed the evidence required of Aristotelian Empiricism. A standardized doctrine had been established and from henceforth citizens would know what rituals were to be taught. Standardization of “authentic” scripture took a bit longer, but great minds had been contemplating the subject for some time. In the second century Irenaeus, bishop of Lyon, had noted that “4” is a perfect number. “There are four rivers in Paradise. There are four elements, winds from four directions, and four corners of the earth. Therefore the New Testament should have four gospels, no more, no less.”3 (Those four perfect books became identified as the Gospels: Matthew, Mark, Luke and John). Athanasius of Alexandria (who is credited with writing the Nicene Creed) later listed the 27 books that should be recognized.4 Twenty-seven derives from two other perfect numbers, “3” and “3” times itself creating the perfection of “9.” “9” times “3” culminates in the consummate perfection of “27.”5 Once the authoritative scriptures were established, they were copied at state expense.

It took longer to standardize Christian religious music, with the project accomplished in the late sixth century by Pope Gregory the Great. Christian music had derived from the Hebrew Book of Psalms. The Rule of St. Benedict (534 CE) required that all 150 Psalms be memorized and sung over the course of each week. Fortunately, with eight to ten “offices” per day6 there were numerous opportunities to sing the 3000 melodies, but still, the quantity to be memorized was a tremendous task. Imagine the joy when Pope Gregory had the melodies written down.7 (While Pope Gregory’s project satisfied a need, it also limited the creation of new music until Vatican Council II in 1965.)

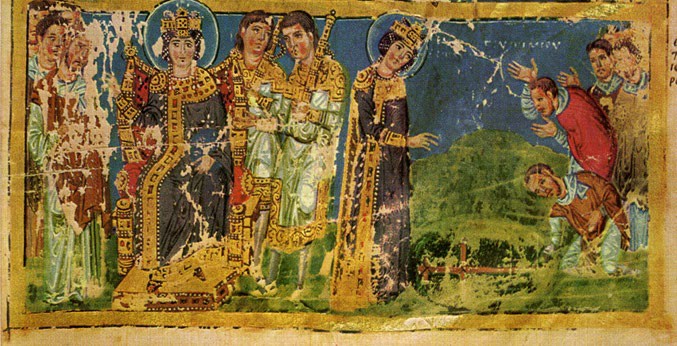

As we have seen8 Constantine was fascinated with physical things that encapsulate the sacred, identified by us as relics. He sent his mother off to the Holy Land in 326-328 to bring home “Mysteries of the Passion” that would give validity and power to the Christian story [image 7.90]. She returned with pieces of the cross, nails, a lance, and the crown of thorns. In 335 Constantine himself followed in search of body fragments, possessions of saints—anything that would allow the faithful to know God.

Far be it for me to criticize one’s devotion to relics when my culture clamors for all things glittered with “star dust:” craving for Elvis’ bath water, scrambling for a clip of Justin Bieber’s hair (which sold in 2011 for $40,668), engaging in riotous behavior or fainting at pop concerts.

Remember your own losses. Remember how you hungered for the smallest of souvenirs when someone you loved died. Anyone who has kept a snapshot of a lover and felt moved to kiss it, or has opened cupboards of a dead friend and felt the onrush of despair evoked by his or her presence in all that jumble of personal possessions has in a way had the same experience sought by the pilgrim when he gazed on Christ’s face painted on Veronica’s veil or worshipped at a relic of the True Cross.

In your more empirical moments, however, you may be more inclined to agree with Chaucer’s analysis of The Pardoner (Indulgence Seller) as told in his General Introduction to the Canterbury Tales:

There was no pardoner of equal grace,

for in his trunk he had a pillow-case

which he asserted was Our Lady’s veil.

He said he had a goblet of the sail

St. Peter had the time when he

made bold to walk the waves,

till Jesu Christ took hold.

He had a cross of metal set with stones,

and in a glass, a rubble of pig’s bones.

Relics (even an old pillow-case!) have no material value, but they do have spiritual strength. To quote the papal secretary St. Jerome (340-420), “We honor the martyr’s relics….because we honor Him Whose witness they are…we honor the servants, that the honor shown to them may reflect on their Master.”10 For the Emperor Constantine, this spiritual strength was enough to promote three types of relics: places, things and holy pictures.

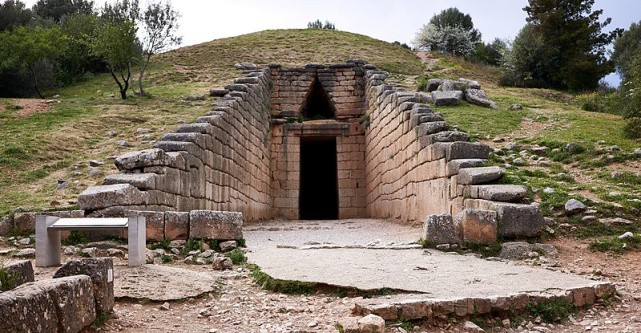

Relics as places. There has often been a need to give geographical expression to specific memories or beliefs. The Roman basilica plan was effective for processions, but a second type of plan, the tholos (aka central plan), was also created for holy relics, a tomb, or a baptistery. This round-dome building type will become as important as the rectangular basilica.

This circular tholos (aka beehive tomb structure) was constructed during the Mycenaean era (1400-1100 BCE) in Bronze Age Greece [images 7.91 and 7.92]. It probably had no relationship with either Atreus (the father of Agamemnon) or Agamemnon, but it was so monumental and impressive that archaeologists gave it the sovereign’s name. It is easy to understand how the visitor’s gaze is drawn upward to the domed ceiling of the corbelled vault.

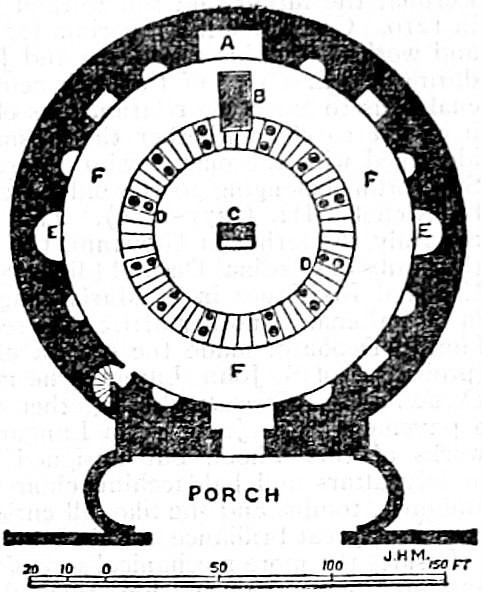

On Mt. Parnassus, at the “center of the earth,” we find the altar to Athena Pronaia [image 7.93]. (The Oracle of Apollo, which used to give advice from this site, was abolished by Theodosius in 393 when the emperor made Christianity the official religion of the Roman Empire.) Since ancient times the circle has represented timeless, the eternal present of the heavenly realm.

The circular area in the center of the Greek theater [image 7.94] was known as the orcheisthai. Dionysus’ altar was in the center of this stage. Gods could be distinguished from other actors because they wore shoes on the sacred dancing place14; others went barefoot. The stage was for drama, yes, but also for dance, songs, and celebrations in honor of the god Dionysus.

The Pantheon in Rome [images 7.95 and 7.96] was dedicated to “all” the gods. Like the tholos in Mycenae, the viewer’s gaze is drawn upwards toward the oculus. As the superlative example of both exterior and interior harmony, its size and resolution of both structural and aesthetic challenges made this a three-dimensional textbook for centuries.

The emperor Constantine might have been directly responsible for this mausoleum dedicated to his daughter, Costantina [images 7.97-7.100]. The ambulatory (a barrel-vaulted passage) encircles the domed interior, accommodating pilgrims, who can’t help but look up to admire the ceiling.

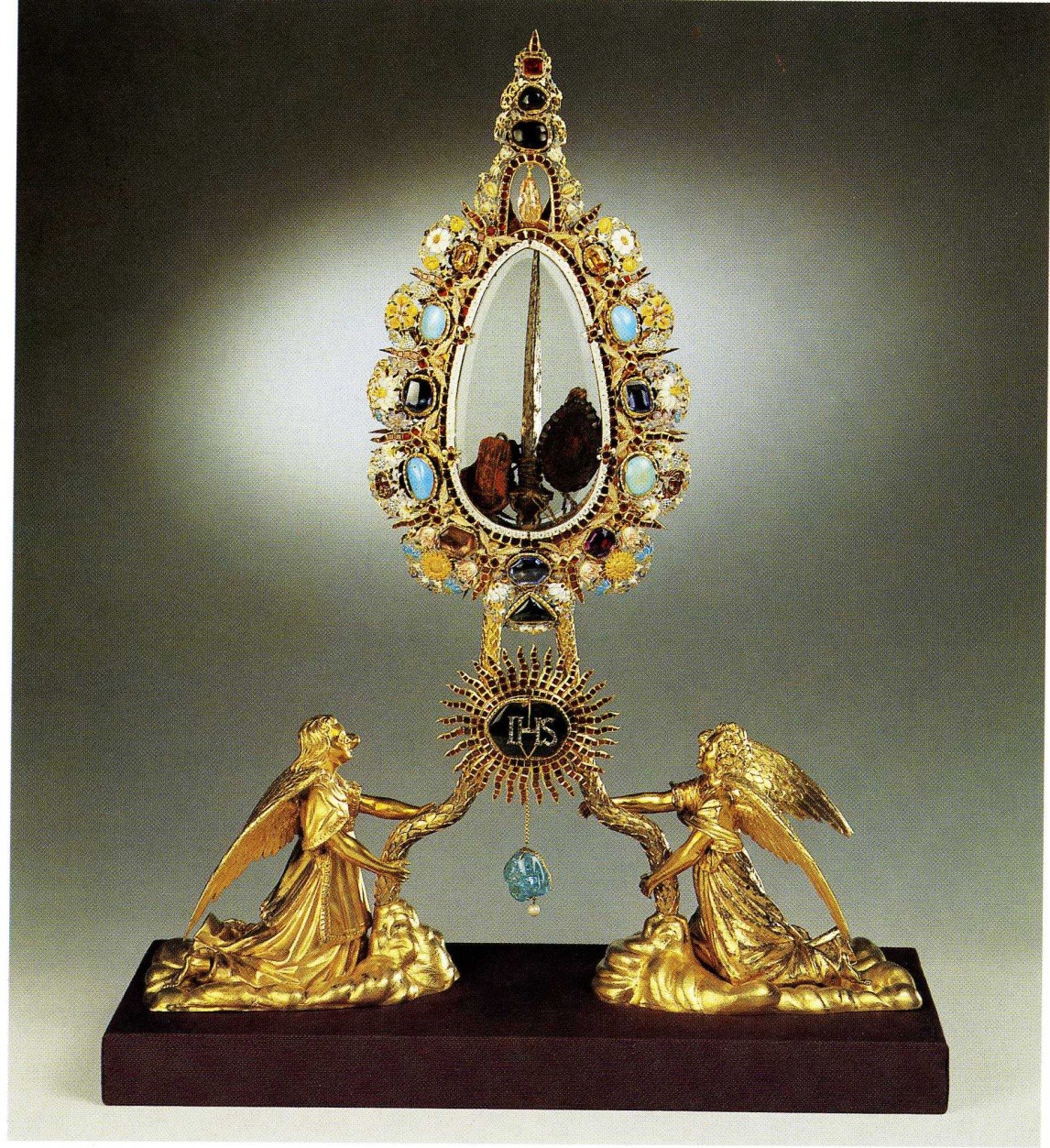

Relics as things. Items which had belonged to saints were particularly precious and many have been saved. Believing that this nail came from Christ’s right hand when he had been nailed to the cross, Constantine had the relic worked into his helmet. Jewelsmiths in 17th century Augsburg adorned it with gold, silver, enameling, emeralds, sapphires, topaz, amethyst, and other precious gems. The rock-crystal in which it is housed was believed to have represented the Transfiguration. Believing in its strong healing power, visitors would rub their rosaries on the capsule [image 7.101].

Both of these reliquaries were fashioned in the style of a Gothic edifice. As such, each forms an elaborate architectural frame for a translucent rock-crystal vessel from 10th century Egypt. Rock crystal was considered a precious stone in the medieval Islamic world and was used to create a number of luxurious secular objects, such as containers for fragrant oil. The silver-gilt reliquary in image 7.102 was probably assembled in Lower Saxony between 1400 and 1500. The reliquary in image 7.103 is from Braunschweig in north-central Germany and is dated to 1375-1400. An inscription along the base specifically identifies the relic as a tooth of Saint John the Baptist.

The holy gown [image 7.104] was believed to have been worn by Mary, either when she gave birth to Christ, or at the time of the Annunciation. Whichever was the “correct” story, it was a gift to Charlemagne from the Empress Irene of Byzantium in 876. The citizens of Chartres believed that it gave protection in 911 when the city was besieged by the Vikings, and it has always been a good source of income! The reliquary in which it is displayed, of course, is modern.

Relics as holy pictures. You will certainly get your fill of holy pictures as we examine Byzantine-influenced churches in Ravenna and Constantinople. For a “preview,” here is a portrayal of the Good Shepherd at the Mausoleum of Galla Placidia in Ravenna [image 7.105].

This is no ordinary shepherd. How do we know that “kingship” is suggested? The mosaic is filled with symbols, which are the language of religion in the same way that numbers are the language of science. Actually, this entire discussion on “Relics” has really been about “symbols.” When you learn to read the symbols, you will be understanding the mystical, complex ideas of the Byzantine era.

A MUSICAL REACTION TO “LOOKING UP” TOWARD A DOME

The Gregorian Chant is still intentionally “singing the words back to God which He has given to us,” but, it is now a step removed from Plainchant music. Or perhaps, it should be said music has advanced by two steps.

First step: Gregorian chant may be sung antiphonally, in parallel halves.27 The musicians are divided into two parts: the cantor, who established the pitch and gave the solo intonation, and the choral response to the stimulus.

Therefore, the music is known as responsorial (solo and chorus).

The second step was a decorative flourish added to the melody. The melody was probably based upon a well- known tune, but in a melismatic touch a single syllable has been elaborated upon and extended over several notes. Look up! Listen up! This is new!

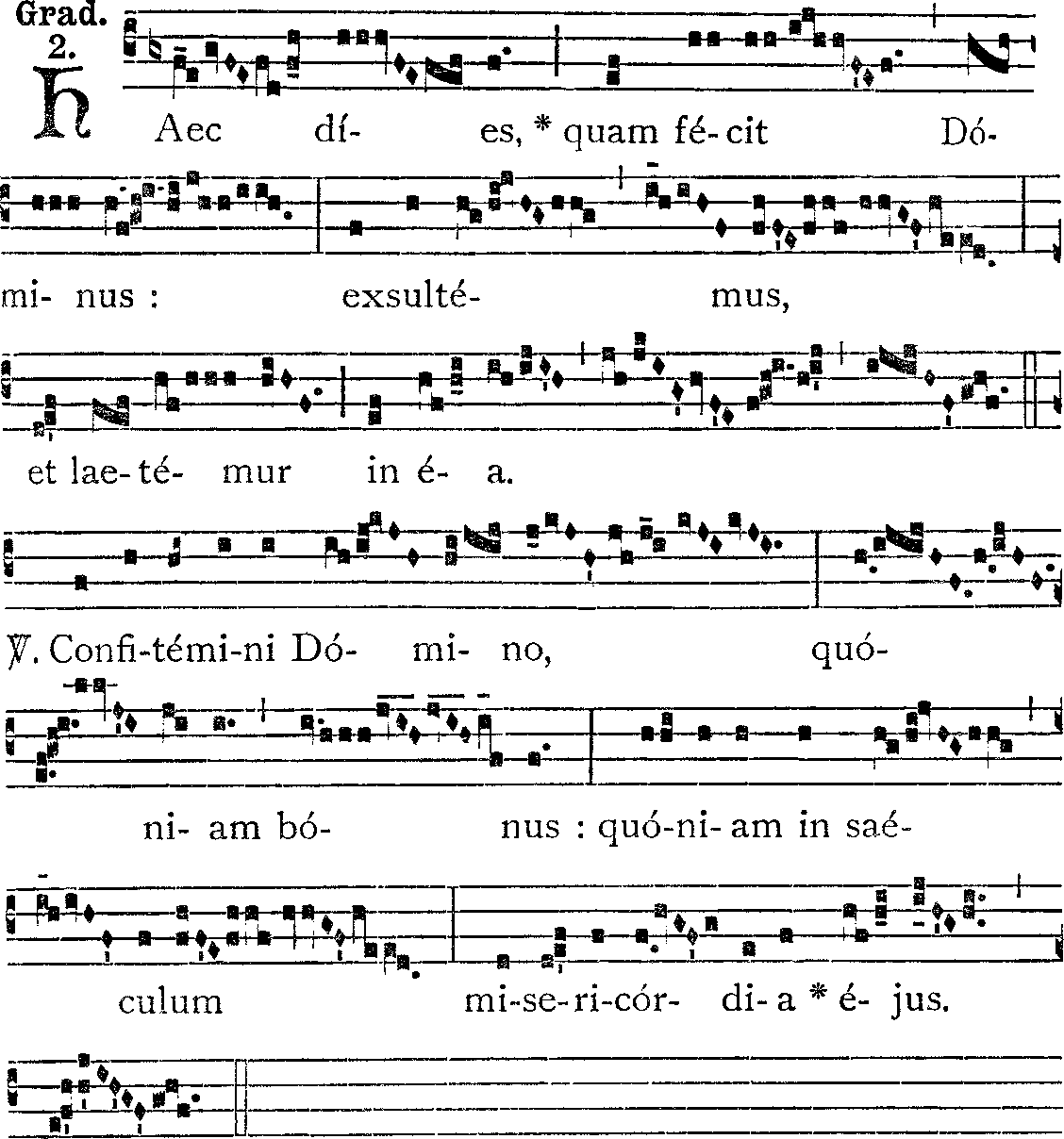

“Haec Dies” is a Gregorian Chant which was based Psalms 118:24 and 106:1. The text would have been appropriate for Easter Sunday.

Haec dies This is the day

quan fecit Dominus. which the Lord hath made;

exsultemus ea we will rejoice and be

laetemur in ea. glad of it.

Confitemini Domino O give thanks to the

quoniam bonus: Lord, for He is good:

quoniam in saeculum for His mercy

misericordia endureth

ejus. Forever.

The first phrase, “Haec dies” is sung as a solo intonation by the cantor. (On this score, the script looks like “Aec dí- es.” Don’t let that fool you.)

The remainder of the hymn, “quan fecit…” is sung as a choral response.

The melismatic flourish extends over important words, such as Dominus and exsultemus.

Significant elements:

The rhythm is dependent on the words.

The pitch is also dependent on the words. The voice moves up and down just as we do when speaking.

Because of the syllabic nature of this music, the meter is unmeasured. Besides, spiritual “truth” is beyond all restrictions of time. God is beyond counting, beyond numbers, beyond rational understanding.

The harmony is monophonic; there is, after all, one God so his oneness should be emphasized.

The instrumentation is “a cappella”—only voices, praising God in unison.

How does the music offer an interpretation of the text? Does the music make any sense as a melody without words?

It is not memorable on its own. There are no phrases, there is no inner logic.

What are the similarities between the Platonic and early Christian views of music?

References:

1. “Ecumenical” means “all-world,” but in this case, “all-Mediterranean” is closer to reality.

2. Loyolapress.com/our-catholic-faith/prayer/traditional-catholic-prayers/prayers-every-catholic-should-know/Nicene-creed

3. Against Heresies, Book III, Chapter 11.

4. The 39th Festal Letter of Athanasius, 367 CE.

5. This number may sound familiar. You might remember that according to Thucydides, the Peloponnesian War lasted 27 years. However long it lasted, it was an auspicious number.

6. Depending on the time of the year, monks would rise between 1:30 and 3:00 AM for “nocturne” or “vigil” and have “vespers” (night prayers) between 4:15 and 5:45. Between these times there were eight “offices” (services) as well as time for manual labor and daily study.

7. Gregory lived from 540 to 604; he was Pope from 590-604. In the absence of the Roman Imperial government, the church had assumed much of the responsibility for food supply, organ amenities, and even defense against the Lombards—therefore, Pope Gregory became the quasi-ruler in the old Imperial capital of Rome.

8. See Hartman, Kathleen J. “Chapter 7, The Ambition of Constantine.” Humanities: New Meaning from the Ancient World. Colorado Springs, CO: Pikes Peak Community College, 2020. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

9. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Biblioth%C3%A8que_ Nationale_MS_Gr._510# /media/File: Homilies_of_Gregory_the_Theologian_gr._510,_f_891.jpg

10. St. Jerome, Ad Riparium, i, P.L., XXII, 907.

11. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File: The_tholos_tomb_Treasury_of_Atreus_or_Tomb_ of_Agamemnon_in_ Mycenae.jpg

12. Ibid.

13. Public domain at https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_tholos_of_Athena_Pronaia.jpg

14. Exodus 3:5 relates how Moses was told “put off thy shoes from off thy feet, for the place whereon thou standest is holy ground” (KJV).

15. Photo by Syenna Tindall, friend of the author, 2017. Used by permission. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

16. Pantheon aerial view / Getty Images, Creative Commons cited on brewminate.com/rome-and-a-villa-hadrians-pantheon-and-tivoli- retreat/

17. Photo by the author, Kathleen J. Hartman, 2006. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

18. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:EB1911_Rome_-_Plan_of_Church_and_Mausoleum_of_Constanza.jpg

19. Photo courtesy of santagnese.org, Creative Commons License (CC BY-SA 2.0).

20. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:S_Costanza_1160909-10-11.JPG

21. Photo by the author, Kathleen J. Hartman, 2017. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

22. Photo by the author, Kathleen J. Hartman, 2010. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

23. Photo by the author, Kathleen J. Hartman, 2006. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

24. Photo by the author, Kathleen J. Hartman, 2016. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

25. Public domain at upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/8/8a/Chartres_cathedral_2850.jpg

26. Photo by the author, Kathleen J. Hartman, 2016. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

27. “Antiphonal” is the root of our word “anthem.”