7.5 The Ambition of Constantine

Constantine was a dreamer and a visionary. Constantine imagined power, and when Diocletian and Maximian retired from their positions as joint Augusti (Emperors) of Rome in 305 CE Constantine saw the possibility of viewing his dreams in vivid Technicolor.

Diocletian’s arrangement for the rule of the Tetrarchs had been to avoid the entanglements of biological succession with a non-hereditary transfer of leadership. Upon the retirement or death of either of the two Augusti, the Caesars (subordinates) were to be advanced to the position of Emperor. But given the simultaneous retirement of both Augusti, the army, and ambitious sons, preferred the biological tradition. The primary contenders for the throne were Maxentius (son of former Augusti Maximian and the son-in-law of Caesar Galerius) and Constantine (son of the Caesar Constantius I Chlorus).

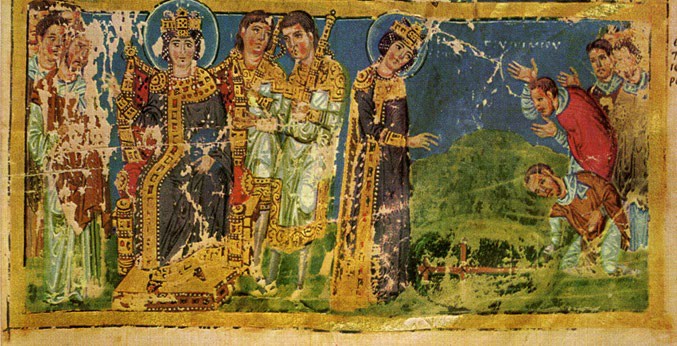

Constantine’s ambition was interpreted in this ninth century manuscript illumination [image 7.23]. On the evening of October 27, 312 his army was camped on the banks of the Tiber River on the outskirts of Rome and preparing to march against the army of Augustus Maxentius. According to tradition Constantine and every man under his command saw a cross of light shining in the sky. In a vision that would become crucial to subsequent European history, Christ appeared holding a flaming cross and proclaiming “In hoc signo vinces” (“In this sign you shall conquer”). Constantine had no idea of the meaning of the unfamiliar emblem; he was not a Christian, though there were likely some Christians among his advisers.

Waste no time! Constantine ordered the battle shields inscribed with the flaming cross, an insignia that resembled the Greek letters Chi (X) and Rho (P) [images 7.24 and 7.25]. What could  possibly mean? The monogram could have been an abbreviation for the Greek “XPICTOC” which means Christos or the Messiah, a great and powerful figure who would overthrow the enemy. Or, it could have been a compression of the Greek word “XPECTOC” which translates as Chrestos or auspicious. Or, it could have been a symbol of power, similar to the scepter and shepherd’s crook held by the pharaoh. Or, invert the sequence and it could have been a signal for P_X, peace!

possibly mean? The monogram could have been an abbreviation for the Greek “XPICTOC” which means Christos or the Messiah, a great and powerful figure who would overthrow the enemy. Or, it could have been a compression of the Greek word “XPECTOC” which translates as Chrestos or auspicious. Or, it could have been a symbol of power, similar to the scepter and shepherd’s crook held by the pharaoh. Or, invert the sequence and it could have been a signal for P_X, peace!

Whatever the “real” meaning of the insignia, on the next day, October 28, 312, under that sign, Constantine marched against Maximian and won the Battle of Milvian Bridge. Although no one realized it at the time, this battle was a turning point that marked the end of the old Roman Imperial system and the beginning of the Byzantine Empire.

Seven months later, on June 15, 313, Constantine acknowledged the assistance he assumed he had received from the divine Christos with the Edict of Milan. With this declaration he decriminalized Christianity only 10 years after Diocletian had launched the “final suppression.” While Constantine did not mandate Christianity (that would not occur until the reign of Theodosius, 392-395), the Edict did grant the right of religious choice and the restoration of property that had been confiscated.

EDICT OF MILAN, 313 CE

“With sound and most upright reasoning. . . we resolved that authority be refused to no one to follow and choose the observance or form of worship that Christians use, and that authority be granted to each one to give his mind to that form of worship which he deems suitable to himself, to the intent that the Divinity. . . may in all things afford us his wonted care and generosity.”1

The ninth century manuscript illuminations to which we have been referring are together on a single page from a codex known as the Homilies of Saint Gregory of Nazianzus. The tempera on parchment illumination is quite large, measuring 41 cm high (16.5 “) by 30.5 cm wide (12.5”). On the next page [image 7.27] it is reproduced as large as this program allows, but even so it is undersized. The story of Constantine is laid out in three registers. The bottom section [image 7.26] tells of his mother’s pilgrimage to the Holy Land in 326-328. Like any good traveler, St. Helena brought home souvenirs, including shiploads of relics, some tubs of soil from Calvary, the stairs which Christ was believed to have climbed in the palace of Pontius Pilate in Jerusalem and most famously, slivers from the True Cross! It was her fascination with relics, which was shared by her son, Constantine, that introduced the “cult of relics” to the Christian church.

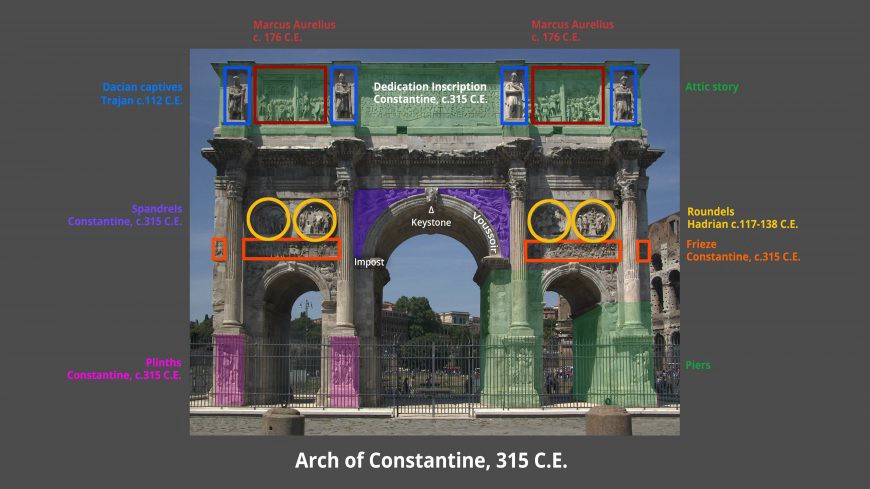

In Rome, “virtue” was defined as manliness, courage and victory in war; these qualities frequently led to fame, wealth and power. Constantine had exemplified his virtue in the 312 Battle of Milvian Bridge, and the proper way to celebrate was with the Roman equivalent to a billboard advertisement, the triumphal arch. In Rome alone there are about 50 of these advertisements. Look around the area in which the Arch of Constantine [image 7.28] was constructed. What does the placement of this arch suggest about Constantine’s piety toward the Roman Empire?

When we walk around to the north face [image 7.29] of this 69’ high monument we see symbols that clearly reveal a man who wanted to be known as the “Restorer of Roman Glory.” Trajan’s conquest of Dacia (Germany) was celebrated inside the central doorway. The medallions on the second story were spolia from a monument to Hadrian, who was also frustrated by the Daciens. On the attic story at the upper right was a depiction of another master of those troublesome Daciens, Marcus Aurelius. Constantine’s association with the emperors Trajan, Hadrian and Marcus Aurelius suggested that, despite sporadic attacks by barbarians, all was well in Rome. “You can look to me as the Pater Patriae.”

There are some divine images on the four supporting columns [images 7.31-7.34], but the arch was not made to promote Constantine as the first Christian emperor, nor is there is any reference to the intervention of a Christian God on Constantine’s side. The huge inscription refers merely to the help of divinitas, but nothing more precise. While original to the arch, the winged divine images are not intended as portrayals of God’s angels. Instead, they remind us of the Assyrian Blessing Genius at the gate of the city of Khorsabad [image 7.35] or the Greek Victory Untying Her Sandal at the Athenian Temple of Athene Nike [image 7.36]. Certainly the inclusion of references to the persecutor Marcus Aurelius was not intended to be complimentary to Christians.

The really surprising feature of this monument is to be seen on the 3’ 4” high horizontal frieze under the medallions [image 7.37]. Here we are convinced of the developing Byzantine cultural values of Authoritarianism and Idealism. Though Constantine’s head has been broken off (perhaps by some hoodlum in a Roman riot), he is without a doubt formally depicted, in a divine frontal pose, on the speaker’s platform between forward-facing Hadrian and Marcus Aurelius. From this position he distributes wisdom, justice, and largess to the Roman people. The composition has no spatial depth; there are no oblique lines or foreshortening. Neither do the citizens show independent movement; they are not individualized; their heads are in idealistic isocephalic unity and they are lined up like puppets on a string. Each turns in adoring worship of the emperor. They are clearly secondary to the empire to which they belong.

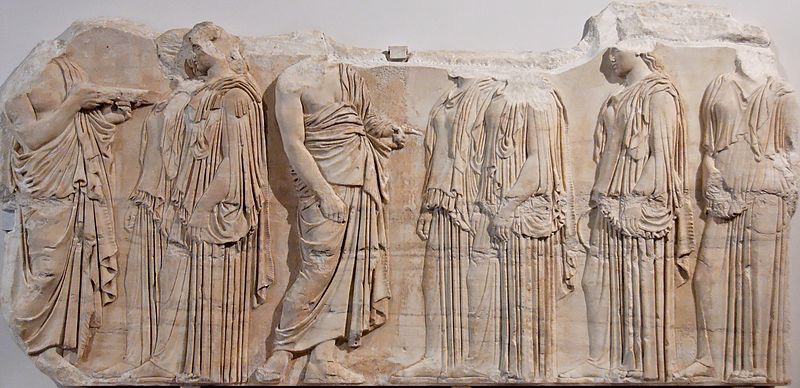

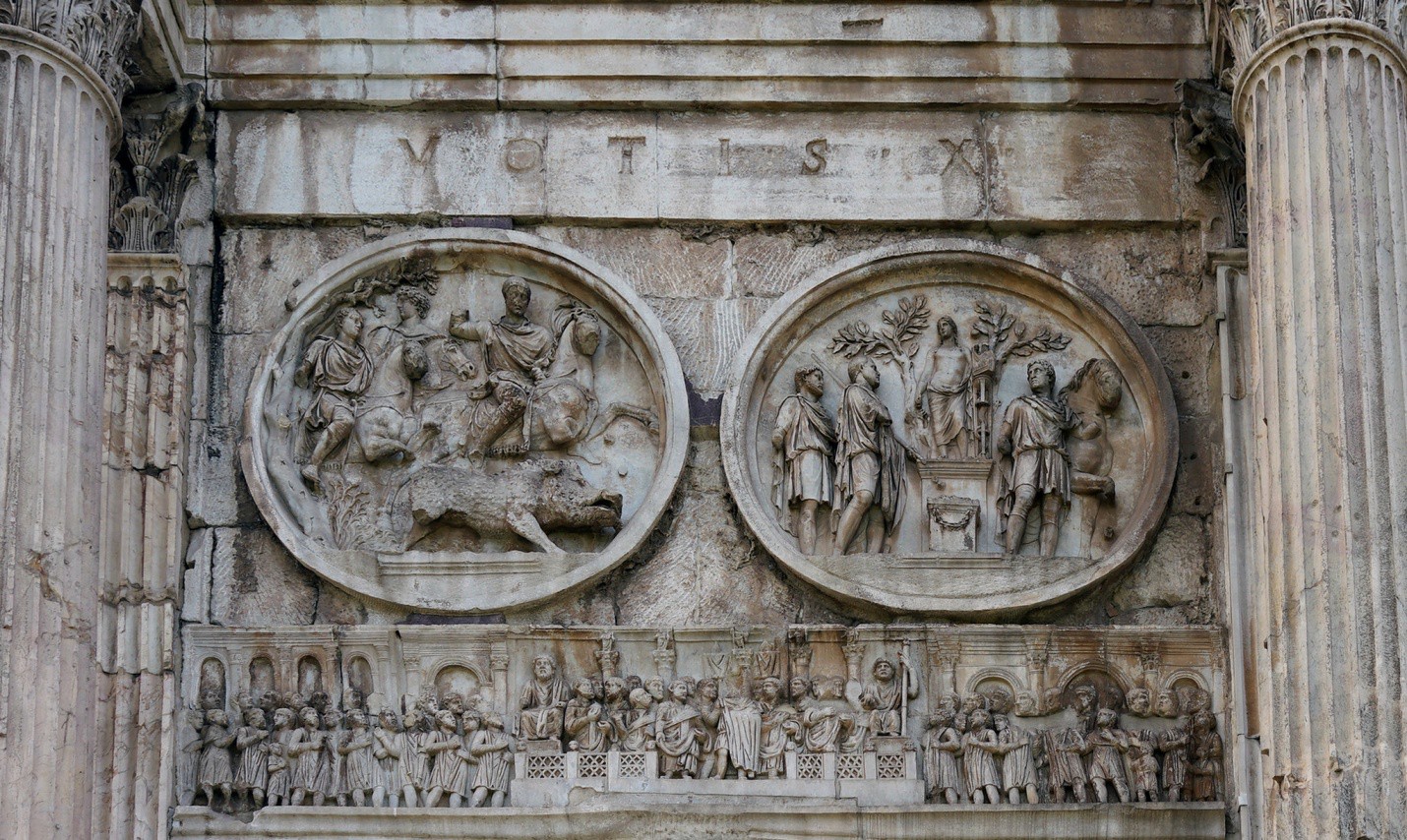

Compare the proportions and spatial depth to earlier processions on both the Parthenon [image 7.38] and the Ara Pacis [image 7.39].

The 40” reliefs [images 7.40 and 7.41] above the frieze give us a comparison view of the citizens and confirm our suspicions. The spolia roundels from the monument to Hadrian were rechiseled with the features of Constantine, but the original, older and more Classical proportions are still evident. Compared to the earlier reliefs, the citizens depicted in the frieze appear to belong to a different race altogether. The contrapposto stance is gone; their forms are insubstantial and generalized; their humanity and dignity have been lost. True beauty now lies in a balanced and orderly society as expressed in the symbolic function of the sculpture. With an authoritarian attitude, the Kingdom has come; the Rule of Caesar is now the Rule of God.

7.41 Two reliefs from the Arch of Constantine: left: roundel showing Sacrifice to Apollo, era of Hadrian, c. 117-138 CE; right: detail, Distribution of Largesse, era of Constantine, 312-315.16

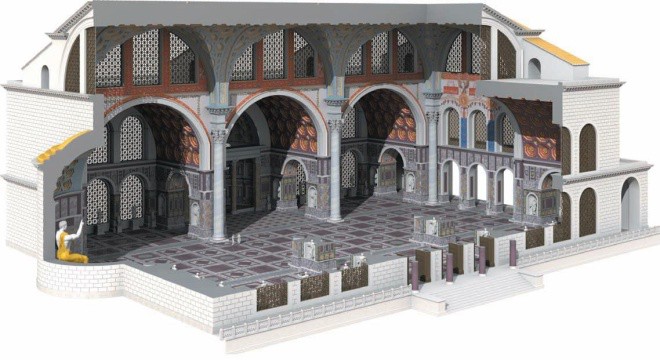

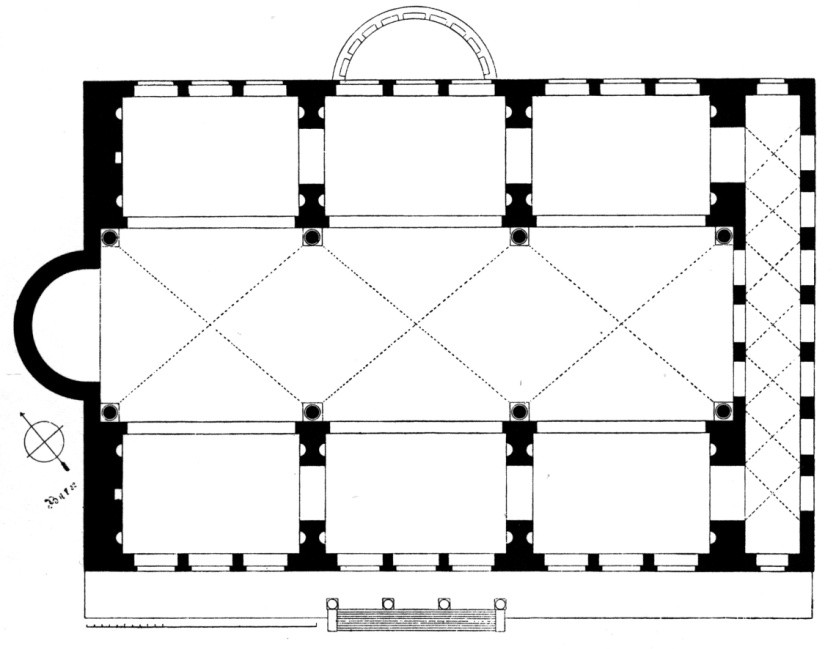

Constantine returned to Rome on the 10th anniversary of his accession to the throne to dedicate this victory arch as well as a new basilica, which is today known as the Basilica Nova [images 7.42-7.44].17 Although the basilica had been started as a Roman bath by Maxentius in 306, Constantine had it transformed into a civic building.

The original apse was on the north-west side (on the left) of this groin-vaulted nave, with the entrance to the south-east (on the right). To accommodate crowds Constantine added an additional entrance on the long side, making the building more similar to Trajan’s Basilica Ulpia. Another apse was added across the hall [image 7.44].

It is speculated that the basilica was being constructed in honor of Maxentius, possibly with a statue of the augustus in the original apse. Constantine’s new apse would dilute the focus, but perhaps that was not a strong enough statement. Whatever had been in the original niche, Constantine had it replaced with a 40’ acrolithic (marble, wood and masonry core sheathed in bronze) seated statue of himself, the Colossal Statue of Constantine the Great [images 7.45]. The acrolithic technique is similar to the chryselephantine (gold and ivory) technique used by Phidias for both his sculpture of Zeus in the Temple of Zeus in Olympia as well as his statue of Athene in the Parthenon. Constantine was sure to have felt honored by the comparison! As a permanent lauratron, it was a lasting symbol of his presence and power.

The bronze sections of the sculpture have disappeared over time, possibly to be repurposed for a military function. The artist’s conception of the full statue [image 7.45] is helpful, but even the marble parts that remain tell a remarkable story about how Constantine viewed himself. Today those parts are lined up in the Palazzo of the Musei Capitolini, Rome [image 7.46].

Which of these three Emperors do you think might have been known as “the visionary”?

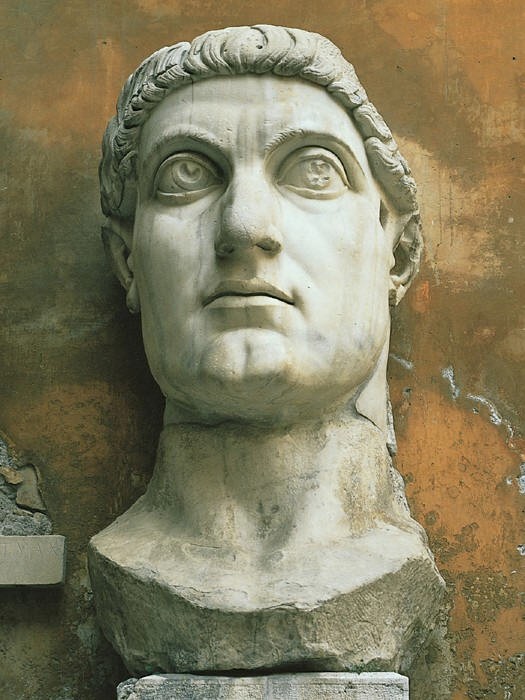

It’s those eyes! It’s that godlike gaze which has experienced the vision of the flaming cross! A tiny fleck of marble had been left in each of Constantine’s eyes to represent the reflection of light in the transparent cornea.

Constantine’s portrait bust [image 7.49] depicts him in a rigidly frontal position with static, absolute, immobility. This is an idealistic portrayal: he is relatively youthful with an unlined face and clean shaven. There is a bit of individualism in his small mouth, massive jaw and nose, and carefully arranged hair which was not tousled like Augustus’. Overall, however, his features were executed on a scale reserved for depictions of gods. His head is 8’ 6” high, and those clear- seeing eyes, which are not looking at his subjects but towards the heavens, are one foot high!

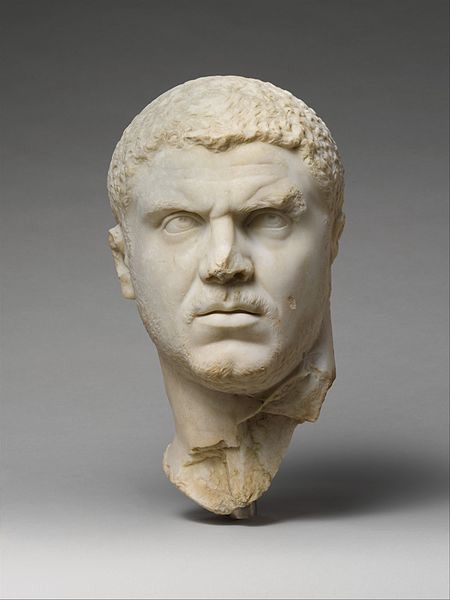

Constantine was not allying himself with the dour Tetrarchs of the Roman Empire [image 7.19]26, nor with terrifying, no-nonsense Caracalla [image 7.48] but with the serene Augustus [image 7.47]. Constantine’s abstract and austere expression represented the sense of authoritarian power that was bolstered by his spiritual vision.

This was a man of unimaginable power. His status was similar to that of the pharaoh Ramesses II [image 7.51]. Both were human, but in a colossal way. (The author’s friend’s hand was resting on Ramesses II’s foot [image 7.50]. I couldn’t resist the comparison and asked my husband to place his hand on Constantine’s foot [image 7.52].)

One God—

One Christ—

One Baptism—

One Religion—

One Empire—

One Emperor.

Constantine’s “One Way” hand [image 7.53] really spoke of his ambition: do whatever was necessary to achieve Oneness. So, we reflect back to the Edict of Milan. Why did he legalize the religion? Why deliberately antagonize the pagan sectors of society? On first glance it would appear he had nothing to gain as only 5-8% of the population was Christian. But, there were four other factors to consider.

- The number of Christians was growing, despite the persecution (or possibly in contempt of the persecution, in spite of the oppression). Others were impressed with the courage and devotion shown by Christians. Bystanders were impressed when some were willing to stay true to the faith even when faced with torture and death. Indeed, the “Cult of the Martyrs,” characterized by violent death, was considered an appropriate initiation into the faith. As Tertullian had proclaimed in the third century, “The blood of the martyrs is the seed of the church.”

- Persecution of the Christians was magnifying theological divisions. Instead of discussing the glories of Imperial Rome, the various factions were spending their energy on doctrinal controversy. A few of the items of debate included:

- WasJesushumanordivine?

- Did he suffer, bleed, and die? Was he resurrected?

- What was the status of Jesus in relationship to God?

- Did he exist prior to his birth?

- Was he born to a Virgin?

- Which literature is authoritative? What about forgeries?

- What should be done about heretics?

- Because the church was not religio licita, it was not one of the approved traditions of the Empire. So, Christians could not own property. (Nor were they responsible for taxes to be paid on that property.)

- The Christian bishops were dedicated, responsible, and trusted by both pagans and the pious. Their fund raising for charitable work had achieved great success. By the year 250 the church in Rome was feeding 1500 poor people and widows each day. During a plague or riot its clergy were the only group to organize food supplies and bury the dead.

Constantine was a pragmatic politician. Christianity was becoming a state within a state. He had a choice of suppressing or integrating the followers of this new religion. By ending the persecution, Christianity could be used as a force for stability.

References:

1. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category: Biblioth%C3%A8que_Nationale_MS_Gr._510# /media/File: Homilies_ of_ Gregory_the_Theologian_gr._510,_f_891.jpg

2. Photo at the Basilica of San Vitale, Ravenna by Kristine Betts, 2019. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

3. Public domain, Homilies_of_Gregory_the_Theologian

4. Ibid.

5. Ibid.

6. Dr. Andrew Findley, “Arch of Constantine, Rome,” in Smarthistory, November 25, 2015, accessed October 7, 2019, smarthistory.org/arch-of-constantine-rome/

7. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Arch_of_Constantine_Rome.jpg

8. Public domain, Dr. Andrew Findley.

9. Photos of divine images on the supporting columns of the Arch of Constantine by the author, Kathleen J. Hartman, 2017. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

10. Accessed at www.louvre.fr/en/pistes-de-visite/cour-khorsabad

11. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:ACMA_973_Nik%C3%A8_sandale_3.JPG

12. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Arch_of_Constantine_forum_frieze.jpg

13. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Egastinai_frieze_Louvre_MR825.jpg

14. Photo by the author, Kathleen J. Hartman, 2017. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

15. Public domain, Dr. Andrew Findley.

16. Ibid.

17. “The Colossus of Constantine,” at https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/ancient-art-civilizations/roman/late-empire/v/colossus- of-constantine

18. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Roma_Basilica_Maxentius.jpg

19. Cited by brewminate.com/art-and-architecture-of-constantine-and-a-new-rome/ from Wikimedia Commons

20. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dehio_6_Basilica_of_Maxentius_Floor_plan.jpg

21. https://www.google.com/url?sa=i&url=https%3A%2F%2Fcanvas.harvard.edu%2Fcourses%2F7918%2Ffiles%2F1927949%2Fdownload%3F verifier%3DWo8SA73sQ16z97jcLUL7LgasWeqQSFct5l7fxboN%26wrap%3D1&psig =AOvVaw21v7SROGEj26J7brqzTYSe&ust =16058380806 35000&source=images&cd=vfe&ved=2ahUKEwiSqpaUw43tAhWNE80KHUKXBt4Qr4kDegQIARBT

22. Photos by the author, Kathleen J. Hartman, 2016. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

23. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Statue-Augustus-2.jpg

24. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Marble_portrait_of_the_emperor_Caracalla_MET_DP123898.jpg

25. Photo by the author, Kathleen J. Hartman, 2016. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

26. See Hartman, Kathleen J. “Constantine: Converting the Empire to Christianity. Brotherly Love in Turbulent Times.” Humanities: New Meaning from the Ancient World. Colorado Springs, CO: Pikes Peak Community College, 2020. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

27. Ibid.

28. Ibid.

29. Public domain at search.creativecommons.org/photos/e887a9a4-ac6c-4374-b54f-0fd12c5f4247

30. Photo by the author, Kathleen J. Hartman, 2016. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.