6.4 The Emperors – 26 BCE to 476 CE

The period from the consolidation of power by Augustus in 27 BCE to the death of the emperor Marcus Aurelius in 180 CE was one of relative peace and prosperity throughout the Roman Empire. For this reason, the Romans themselves referred to this time as the Pax Romana, or Roman peace. During this period, the Empire became a smoothly run bureaucratic machine as commerce prospered, and the overall territory grew to its largest extent in the early second century CE. The model of the city of Rome in Image 6.29, gives us an idea of the massive amount of growth and the many building projects that were implemented to impress the world with the power of the Roman Empire. Note the Coliseum, the Circus Maximus, the Tiber River with its bridges, and the aqueducts that brought water into the city center.

Upon the death of Augustus, some Senators were hoping for the return of the Republic, while others assumed that Augustus’ stepson would inherit his nebulous yet amazingly powerful position.

Augustus adopted his stepson Tiberius Claudius Nero (not to be confused with the later emperor Nero), son of his wife Livia from her first marriage. Over the final years of his life, Augustus gradually shared more of his unofficial powers with Tiberius in order to smooth the process of succession and the Senators conferred upon Tiberius all of Augustus’ previous powers.

Tiberius’ succession is an example of why historians refer to the first Roman imperial dynasty as the Julio-Claudians. There was so much intermarriage and adoption between Julius Caesar’s branch of the family tree and the Claudii Nerones branch of the tree that historians now refer to it as the Julio-Claudian period.

Tiberius appears to have been a reluctant emperor, who preferred life out of the public eye. In 26 CE, he retired to Capri for the final eleven years of his rule. It is a testament to the spectacular bureaucratic system of the Roman Empire that the eleven-year absence of the emperor was hardly felt. Tiberius had a difficult time selecting a successor since each relative who was identified as a candidate died an untimely death. Ultimately, he adopted as his successor his grandnephew Gaius Caligula, or “little boot,” son of the popular military hero Germanicus. While Caligula began his power with full support of both the people and the Senate, and with an unprecedented degree of popularity, he swiftly proved to be mentally unstable and bankrupted the state in his short rule of just less than four years. In 41 CE, he was assassinated by three disgruntled officers in the Praetorian Guard, which ironically was the body formed by Augustus in order to protect the emperor.

The assassination of Caligula left Rome in disarray. While the confused Senate was meeting and planning to declare the restoration of the Roman Republic, the Praetorian Guard proclaimed Claudius as the next emperor. Although Claudius was a member of the imperial family, he was never considered a candidate for succession because he had a speech impediment. As a result, Augustus considered him an embarrassment to the imperial family. Claudius proved to be a productive emperor, but his downfall appears to have been pretty women of bad character, as he repeatedly weathered plots against his life by first one wife and then the next. Finally, in 54 CE, Claudius died and was widely believed to have been poisoned by his wife, Agrippina the Younger. His successor instead became Nero, his stepson, who was only sixteen years old when he gained power.

Showing the danger of inexperience for an emperor, Nero gradually alienated the Senate, the people, and the army over the course of his fourteen-year rule. He destroyed his own reputation by performing on stage—behavior that was considered disgraceful in Roman society. Although Nero did not cause the great fire of Rome in 64 CE, he seized 100 acres in the center of the city after the fire to build his ambitious new palace, the Domus Aurea, or Golden House. This palatial building had a rotating ceiling made to look like the sky, an oculus in the dome over the dining room and precious stones embedded in the walls. In June of 68 CE when the Praetorian Guard rebelled and the military leader Galba marched on Rome with his army, Nero was killed, marking the end of the Julio-Claudian dynasty.

The year and a half after Nero’s death saw more civil war and instability throughout the empire than any other period since the late Republic. In particular, the year 69 CE became known as the year of the four emperors, as four emperors in succession came to power: Galba, Otho, Vitellius, and Vespasian. Each challenged his predecessor to a civil war, and each was as swiftly defeated by the next challenger.

Vespasian, a mere son of a tax-collector, was the only successful emperor of 69 CE and the founder of the Flavian dynasty. He was a talented military commander and was in command of a major military force in 69 CE, since he had been working on subduing the Jewish Revolt since 67 CE. Ironically, Nero had originally appointed him to command the Jewish War because of Vespasian’s humble family origins—which to Nero meant that he was not a political threat. Also, Vespasian was the only one of the four emperors of 69 CE who had grown sons, and thus obvious successors. Furthermore, his older son, Titus, was already a popular military commander in his own right and cemented his reputation even further by his conquest of Jerusalem in 70 CE.

The Flavian dynasty did not last long, as it ended in 96 CE with the assassination of Emperor Domitian, Vespasian’s younger son. The period from 96 CE to 180 CE saw a different experiment in determining imperial succession. Instead of establishing traditional dynasties in which sons succeeded their fathers, this was the period of the “Five Good Emperors” and each emperor adopted a talented leader with potential as his successor.

One of these was the emperor Trajan who ruled from 98 to 117 CE. The best source of information about Roman provincial government is the prolific letter-writer Pliny the Younger, who served as governor of the province of Bithynia on the shore of the Black Sea in 111 – 113 CE. Pliny was a cautious and conscientious governor, and thus believed in consulting the emperor Trajan on every issue he encountered in his province. Luckily for us, their correspondence survives. Pliny’s letters reveal a myriad of problems that the governor was expected to solve: staffing personnel for prisons (is it acceptable to use slaves as prison guards?), building repairs and water supply, abandoned infants and their legal status (should they be considered slave-born or free?), fire brigades (are they a potential security risk to the Empire?) and, most famously, what to do with Christians in the province. The emperor Trajan patiently responded to each letter that he received from Pliny and appears to have placed stability and peace in the province foremost in his concerns. Thus, for instance, with regard to the issue of Christians in Bithynia, Trajan recommends that Pliny not worry about tracking down Christians in his province, as they were not a threat.

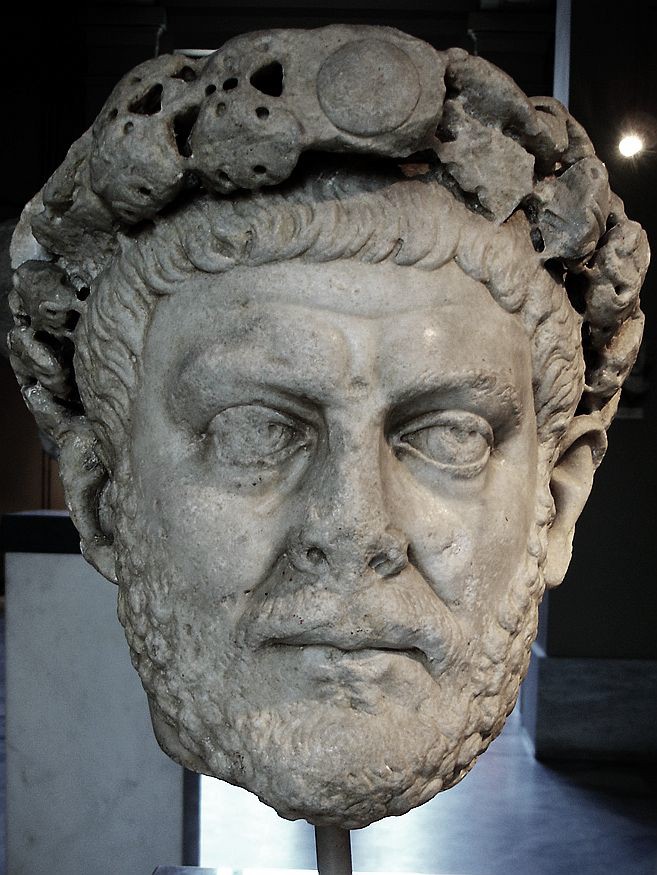

While the second century CE was a time when the Empire flourished, the third century was a time of crisis, defined by political instability and civil wars, which ultimately demonstrated that the Empire had become too large to be effectively controlled by one ruler. In addition to political upheaval and near-constant civil wars, the Empire was also dealing with increasing pressures on the frontiers, a plague that devastated the population, famine, and rampant inflation. The third- century crisis showed that a single emperor stationed in Rome was no longer equipped to deal with the challenges of ruling such a vast territory. The man who ended the crisis was the emperor Diocletian. Born to a socially insignificant family in the province of Dalmatia, Diocletian had a successful military career. Proclaimed emperor by his troops in 284 CE, Diocletian promptly displayed a political acumen that none of his predecessors in the third century possessed. Realizing that a single emperor in charge of the entire empire was a “sitting duck,” whose assassination would throw the entire empire into yet another civil war, Diocletian established a new system of rule: the Tetrarchy, or the rule of four. He divided the empire into four regions, each with its own capital.

It is important to note that Rome was not the capital of its region. Diocletian clearly wanted to select as capitals cities with strategic importance, taking into account such factors as proximity to problematic frontiers. Of course, as a Dalmatian of low birth, Diocletian also lacked the emotional connection to Rome that the earliest emperors possessed. Two of the regions of the Tetrarchy were ruled by senior emperors, named Augusti (“Augustus” in the singular), and two were ruled by junior emperors, named Caesares (“Caesar” in the singular). One of the Augusti was Diocletian himself, with Maximian as the second Augustus. The two men’s sons-in-law, Galerius and Constantus Chlorus, became the two Caesares. Finally, it is important to note that in addition to reforming imperial rule, Diocletian attempted to address other major problems, such as inflation, by passing the Edict of Maximum Prices. This edict set a maximum price that could be charged on basic goods and services in the Empire. He also significantly increased the imperial bureaucracy. In a nutshell, as some modern historians have described him, Diocletian was the most significant Roman reformer since Augustus.

Diocletian’s political experiment was most clearly successful in achieving one goal: ending the third-century crisis. The four men were able to rule the empire and restore a degree of political stability.

While it succeeded in restoring stability to the Empire, inherent within the Tetrarchy was the question of succession, which turned out to be a much greater problem than Diocletian had anticipated. Hoping to provide for a smooth transition of power, Diocletian abdicated in 305 CE and required Maximian to do the same. The two Caesares, junior emperors, were promptly promoted to Augusti, and two new Caesares were appointed. The following year, however, Constantius Chlorus, a newly minted Augustus, died. His death resulted in a series of wars for succession, which ended Diocletian’s experiment of the Tetrarchy. The wars ended with Constantius’ son, Constantine, reuniting the entire Roman Empire under his rule in 324 CE.

While traditional Roman religion was the ultimate melting pot, organically incorporating a broad variety of new cults and movements from the earliest periods of Roman expansion, Christianity’s monotheistic exclusivity challenged traditional Roman religion and transformed Roman ways of thinking about religion in late antiquity. By the early fourth century CE, historians estimate that about ten percent of those living in the Roman Empire were Christians. With Constantine, however, this changed, and the previously largely underground faith grew exponentially because of the emperor’s endorsement. See Chapter 7 to learn more about Constantine and the changes he implemented.

After the death of the Emperor Theodosius in 395 CE, the Roman Empire became permanently divided into Eastern and Western Empires, with instability and pressures on the frontiers continuing, especially in the West. The sack of Rome by the Goths in 410 CE was followed by continuing raids of Roman territories by the Huns, a nomadic tribe from Eastern Europe, the Caucasus region, and south-eastern China. The Huns experienced an especially prolific period of conquest in the 440s and early 450s CE under the leadership of Attila. While they were not able to hold on to their conquests after Attila’s death in 453 CE, their attacks further destabilized an already weakened Western Roman Empire. Finally, the deposition of the Emperor Romulus Augustulus in 476 CE marked the end of the Roman Empire in the West, although the Eastern half of the Empire continued to flourish for another thousand years.

The fall of the Roman Empire in the West, however, was not really as clear and dramatic a fall as might seem. A number of tribes carved out territories, each for its own control. Over the next five hundred years, led by ambitious tribal chiefs, these territories coalesced into actual kingdoms. Rome was gone, yet its specter loomed large over these tribes and their leaders, who spoke increasingly barbaric forms of Latin, believed in the Christian faith, and dreamed of the title of Roman Emperor.

Attribution:

Berger, Eugene; Israel, George; Miller, Charlotte; Parkinson, Brian; Reeves, Andrew; and Williams, Nadejda, “World History: Cultures, States, and Societies to 1500” (2016). History Open Textbooks. 2.

References:

1. Photo by Carole Raddato, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?search=Model+of+rome&title= Special%3ASearch&go=Go&ns0=1&ns6=1&ns12=1&ns14=1&ns100=1&ns106=1#/media/File:Model_of_imperial_Rome,_Area_of_the_Velian_Hill_and_the_Valley_of_the_Colosseum_in_I._Gismondi’s_large_1987_model_of_Rome,_Museo_della_Civita_Romana_(13841003315). jpg

2. Photo by Richard Mortel, CC BY 2.0.https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Emperor_Tiberius,_d._37_CE,_National_Archeological_Museum,_Madrid_(1)_(29328381216).jpg

3.Photo by PierreSelim.Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?sort=relevance&search=File%3ARoman+busts.JPG&title=Special%3ASea rch&profile=advanced&fulltext=1&advancedSearch- current=%7B%7D&ns0= 1&ns6=1&ns12= 1&ns14=1&ns100= 1&ns106=1#/media/File:Caligula_-_MET_-_14.37.jpg

4. Photo by Marie-Lan Nguyen, CC BY 2.5. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?search=Emperor%20Claudius&title=Special%3ASearch&fulltext=1&ns0= 1&ns6=1&ns12=1&ns14=1&ns100=1&ns106=1#/media/File:Claudius_crop.jpg

5. Photo by Giovanni Dall’orto, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:0978_-_Nerone_-_Museo_Archeologico,_Cagliari_-_Photo_by_Giovanni_Dall%27Orto,_November_11_2016.jpg

6. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Imperator_Caesar_Vespasianus_Augustus_Vaux_1.jpg

7. Photo by Richard Mortel, CC BY 2.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=Special:Search&limit=100&offset=0&profile=default&search=Empe ror+Titus&advancedSearch- current={}&ns0=1&ns6=1&ns12=1&ns14=1&ns100=1&ns106=1#/media/File:Titus,_Roman_emperor,_79- 81,_Ny_Carlsberg_Glyptotek,_Copenhagen_(36375008056).jpg

8. Photo by Szilas, public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File: Trajan,_the_Palladium,_and_ Rome%27s_ destiny,_ Colosseum.jpg

9. Photo by Giovanni Dall’orto, CC BY- SA 3.0,https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?search=Diocletian+Istanbul&title =Special%3ASearch&go=Go&ns0=1&ns 6=1&ns12=1&ns14=1&ns100=1&ns106=1#/media/File:Istanbul_-_Museo_archeol._-_Diocleziano _(284-305_d.C.)_-_Foto_G._Dall’Orto_28-5-2006_(ropped_enhanced).jpg