6.2 ROMAN CIVILIZATION INTRODUCTION AND TOPOGRAPHY

As the title of one recent textbook of Roman history puts it, Roman history is, in a nutshell, the story of Rome’s transformation “from village to empire.”1 The history of Rome begins with the legend of Romulus and Remus. It is said that in about 753 BCE, the twin brothers who were said to have been fathered by the gods, were placed in a basket in the Tiber River and were then pulled from the river and suckled by a she wolf. They were found and raised by shepherds and eventually Romulus founded the city of Rome after killing his brother. The she wolf suckling Romulus and Remus is the iconic image of the founding myth of Rome, and there are many sculptures like this one, image 6.10, which tell the city’s founding story.

Today Romans still celebrate the city’s birthday on April 21st with parades and flowers left at ancient monuments. (See image 6.11)

The geography and topography of Rome, Italy, and the Mediterranean world as a whole played a key role in the expansion of the empire but also placed challenges in the Romans’ path, challenges which further shaped their history. Before it became the capital of a major empire, Rome was a village built on seven hills sprawling around the river Tiber.

Set sixteen miles inland, the original Roman settlement had distinct strategic advantages: it was immune to attacks from the sea, and the seven hills on which the city was built were easy to fortify. The Tiber, although marshy, malaria ridden, and prone to flooding, enabled Romans to trade with the neighboring city-states. By the mid-Republic, Roman markets required access to the sea, so the Romans built a harbor at Ostia, which grew to become a full-fledged commercial arm of Rome. Wheeled vehicles were prohibited inside the city of Rome during the day, in order to protect the heavy pedestrian traffic. Thus, at night, carts from Ostia poured into Rome, delivering food and other goods for sale from all over Italy and the Empire.

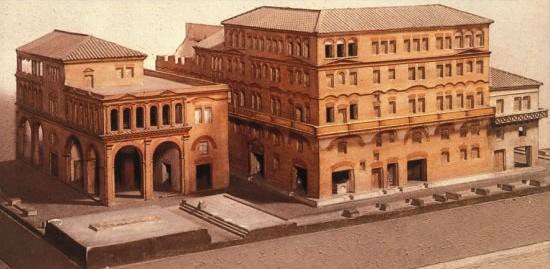

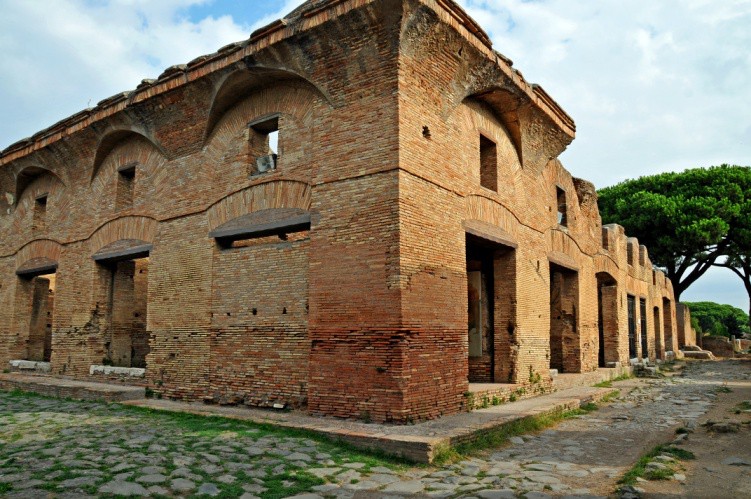

The most common building erected in Rome was the insula. It was built for the commoners by the thousands, and 90% of the population lived in them. We believe that more than 45,000 of these were built, many by profit hungry speculators. In an effort to cut costs, many of the insula were poorly built and collapsed. Often a family lived in the upper stories and ran a small business on the lower floors. See image 6.13 which is a model of an insula and figure 6.14 which shows the ruins of an insula found in the modern city of Ostia. Only the wealthiest inhabitants of buildings like this had plumbing. Most of the people who lived in Rome used continuously flushing public toilets and the public baths.

As Rome built a Mediterranean empire, the city itself grew increasingly larger, reaching a population of one million by 100 CE. While Italy boasted fertile farmlands, feeding the city of Rome became a challenge that required the resources of the larger empire, and Egypt in particular became known as the breadbasket of Rome. As a result, emperors were especially cautious to control access to Egypt by prominent senators and other politicians, for fear of losing control over this key area of the Empire.

A persisting challenge for Roman emperors was that of the location of the empire’s capital. When the Roman Empire consisted of Italy alone, the location of Rome in the middle of the Italian peninsula was the ideal location for the capital. Once the empire controlled huge amounts of territory, the location of Rome was a great distance from all the problem frontiers. As a result, emperors over the course of the second and third centuries spent increasingly less time in Rome.

Finally, Diocletian’s split of the Empire in 293 CE into four administrative regions, each with a regional capital, left Rome out, and in 330 CE, the emperor Constantine permanently moved the capital of the empire to his new city of Constantinople, built at the site of the older Greek city of Byzantium.

The large area encompassed by the empire required a sophisticated infrastructure of roads and sea routes, and the Romans provided both. By the first century CE, these roads and routes connected the center of the empire (Rome) to the periphery, providing ways for armies, politicians, traders, tourists, and students to travel with greater security and speed than ever before.

When Roman roads were well built they offered newly conquered populations a practical way to take their goods to market and stay connected to their neighbors. As primary sources reveal, travel was never a fully safe undertaking, as bandits lurked on the roads and pirates on the seas. Greedy locals were always eager to fleece unsuspecting tourists, and shipwrecks were an unfortunate common reality. Still, the empire created an unprecedented degree of networks and connections that allowed anyone in one part of the empire to be able to travel to any other part, provided he was wealthy enough to be able to afford the journey. See image 6.15 for an example of a cobblestone road built in the Coliseum complex that is still in use today.

The main energies of Rome were devoted to conquest and administration. Roman troops were well disciplined, tenacious, practical and obedient. Roman cities sprung up all around the Mediterranean and as far north as the Danube, the Rhine, and the Thames. Each city was a center for the propagation of Roman government, language, and customs.

Rome sought to impress upon all of its outlying provinces that it was a powerful, dignified, and diverse state.

After the fall of the Etruscan kings, historians divide Roman history into two major periods: the Republic which ruled Rome from the late sixth century BCE to the late first century BCE, and the Empire from the late first century BCE to the fall of the Western half of the empire in the late fifth century CE. During the Republican period power was theoretically distributed among all Roman citizens. In practice, this was really an aristocratic oligarchy. By contrast, under the Empire, Rome was under one ruler, the Emperor.

This is a general chronology of the dates we will use to discuss Rome. These dates are not absolute but can be helpful to understand Roman history.

- 800 BCE-300 BCE– Etruscan culture 753 BCE – Founding of Rome

- c. 753-510 BCE – Regal Period

- c. 510-44 BCE – Roman Republic 44 BCE – 476 CE – Roman Empire

- 44 BCE – 68 CE – Julio-Claudian Dynasty 69 CE – Year of the Four Emperors

- 69-96 CE – Flavian Dynasty

- 96-180 CE – The Five Good Emperors 235-284 CE – The Third Century Crisis

- 395 CE – Permanent division of the Empire into East and West

Attribution:

Berger, Eugene; Israel, George; Miller, Charlotte; Parkinson, Brian; Reeves, Andrew; and Williams, Nadejda, “World History: Cultures, States, and Societies to 1500” (2016). History Open Textbooks. 2.

References:

1. Mary Boatwright, Daniel Gargola, Noel Lenski, and Richard Talbert. The Romans: From Village to Empire: A History of Rome from Earliest Times to the End of the Western Empire (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011).

2. Photo by Jastrow, Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?search=She%20wolf%20&title=Special%3ASearch&fulltext=1&ns0=1&ns6=1&ns12=1 &ns14=1&ns100=1&ns106=1#/media/File:Capitoline_she-wolf_Musei_Capitolini_MC1181.jpg

3. Photo by Kristine Betts, CC BY-NC-4.0 License.

4. By Renata3, CC BY-SA 4.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?search=Map+of+the+seven+hills+of+ Rome&title= Special%3ASearch&go=Go&ns0=1& ns6=1&ns12=1&ns14=1&ns100=1&ns106=1#/media/File:Seven_Hills_of_Rome.svg

5. Photo by Bjankuloski06, Public Domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?search= Ostia+insula&title= Special%3ASearch&go=Go&ns0=1&ns6=1&ns12=1&ns14= 1&ns100=1&ns106=1#/media/File:Insula2.jpg

6. Photo by Dennis Jarvis, CC BY-SA 2.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?search=Ostia+insula&title= Special%3ASearch&go= Go&ns0=1&ns6=1&ns12=1&ns14= 1&ns100=1&ns106=1#/media/File:Insula_in_Ostia.jpg

7. Photo by Kristine Betts, CC BY-NC-4.0 License.