5.2 Pergamon

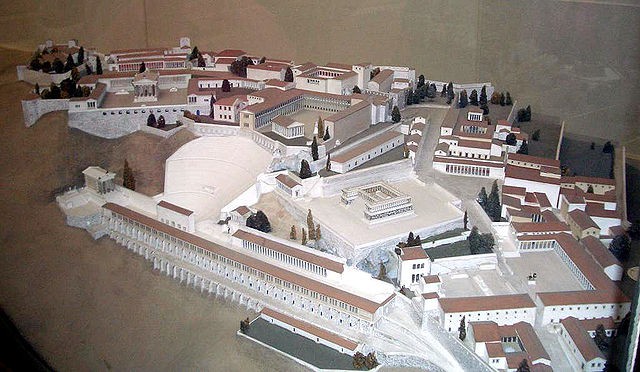

The ancient city of Pergamon, now modern day Bergama in Turkey, was the capital of the Kingdom of Pergamon following the death of Alexander the Great and was ruled under the Attalid dynasty. The Acropolis of Pergamon is a prime example of Hellenistic architecture and the convergence of nature and architectural design to create dramatic and theatrical sites. The buildings on the acropolis were built into and on top of a steep hill that commanded great views of the surrounding countryside. Both the upper and lower portions of the acropolis were home to many important structures of urban life, including gymnasiums, agorae, baths, libraries, a theater, shrines, temples, and altars. Culturally speaking, Pergamon had become the jewel of the known world.

The theater at Pergamon could seat 10,000 people and was one of the steepest theaters in the ancient world. Like all Hellenic theaters, it was built into the hillside, which supported the structure and provided stadium seating that overlooked the ancient city and its surrounding countryside. The theater is one example of the creation and use of dramatic and theatrical architecture.

Theatre continued to be popular during the Hellenistic Age. The comedies pioneered by Aristophanes during the high Classical period and after the fall of the Democracy developed into a style more appropriate to areas under the rule of kings. The speech in which the playwright made a serious point was eliminated. The Greek poet, Menander, introduced a new character type, the clever slave. This gave people a character that they could relate to as well as the opportunity to watch the slave outwit his master.

THE ALTAR OF ZEUS

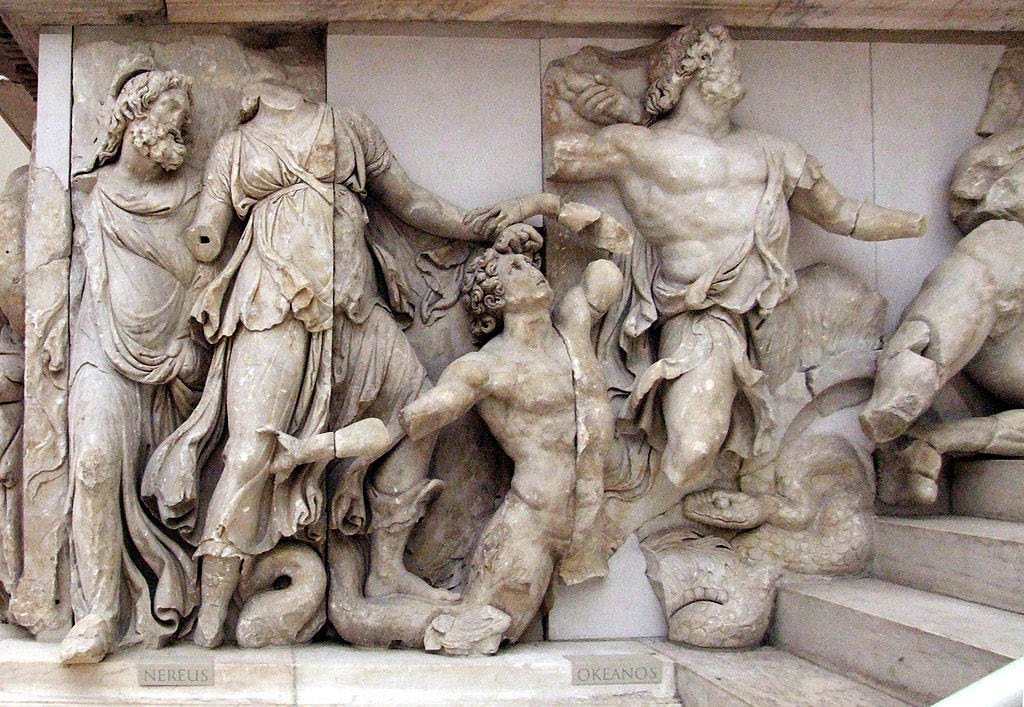

Another architectural wonder found at Pergamon is the great Altar of Zeus, now housed in Berlin, Germany. The altar was commissioned in the first half of the second century BCE, during the reign of King Eumenes II to commemorate his victory over the Gauls, who were migrating into Asia Minor. The Gauls were an ancient, often nomadic people that lived in northern Europe and became known for attacking and pillaging wealthy cities such as Pergamon and Rome. The altar was a U-shaped Ionic building built on a high platform, an idea borrowed from the Persians, with central steps leading to the top. It faced east, was located near the theater of Pergamon, and commanded an outstanding view of the region. The altar is known for its grand design and for its frieze, which wrapped 370 feet around the base of the altar depicting gigantomachy, which refers to the battle between the giants of the Titans and the Olympians, and was led by Zeus.

The gigantomachy depicts the Olympian gods fighting against their predecessors the Giants (Titans) who were the children of the goddess, Gaia. The frieze is known for its incredibly high relief, in which the figures are barely restrained by the wall, and for its deep drilling of lines with details that create dramatic shadows. The high relief and deep drilling also increased the liveliness and naturalism of the scene.

The figures are rendered with high plasticity. The texture of their skin, drapery, and scales add another level of naturalism. Furthermore, as the frieze follows the stairs, the limbs of the figures begin to spill out of their frame and onto the stairs, physically breaking into the space of the viewer. The style and high drama of the scenes is often referred to as the Hellenistic Baroque for its exaggerated motion, emphasis on details, and the liveliness of the characters.

The most famous scene on the frieze depicts Athena fighting the giant Alkyoneus. She grabs his head and pulls it back while Gaia emerges from the ground to plead for her son’s life and a winged Nike reaches over to crown Athena. Athena’s drapery swirls around her with deep folds and her whole body is nearly removed from the frieze. The figures are depicted with the heightened emotion commonly found on Hellenistic statues. Alkyoneus’s face strains in pain and Gaia’s eyes, which are all that remain of her face, are full of terror and sorrow at the death of her son.

The entire composition is depicted in a chiastic shape. A chiasm is a figure that repeats concepts in reverse order in the same or a modified form. Athena stretches out to grasps Alkoyneus’s head, the two figures pull at each other in opposite directions. Meanwhile, the figure of Nike moves diagonally towards Athena, showing their convergence in a moment of victory. The diagonal line created by Gaia mimics the shape of her son, connecting the two figures through line and pathos. The scene is filled with the tension and emotion that are key features in Hellenistic sculpture.

THE DYING GAULS

A group of statues depicting dying Gauls, the defeated enemies of the Attalids, was situated inside the Altar of Zeus. The court sculptor, Epigonus, is believed to have cast the original set of statues in bronze in 230-220 BCE. Now, only marble Roman copies of the figures remain. Like the figures on the frieze and other Hellenistic sculptures, the figures are depicted with lifelike details and a high level of naturalism. They are also depicted in the common motif of barbarians. A motif is a recurring subject or theme, often found in design. The men are nude and wear Gallic torcs. A torc was a neck ring, often brass, that signified the warrior class. Their hair is shaggy and disheveled. The figures are positioned in dramatic compositions and are shown dying heroically, which turns them into worthy adversaries, increasing the perception of power of the Attalid dynasty.

One Gaul is depicted lying down, supporting himself over his shield and a discarded trumpet. He furrows his brow as he looks at his sword and at his own image, reflected there, as he prepares himself for death. His muscles are large and strong, signifying his strength as a warrior and implying the strength of the one who struck him down.

Two other figures complete the group. One figure depicts a Gallic chief committing suicide after he has killed his own wife. Also known as the Ludovisi Gaul, this sculpture group displays another heroic and noble deed of the foes, for typically women and children of the defeated would be murdered to avoid their being captured and sold as slaves by the victors. The chief holds his fallen wife by the arm as he plunges his sword into his chest, where blood is already exiting the wound. All three figures in the group are depicted in a Hellenistic manner. To fully appreciate the statues, it is best to walk around them. Their pain, nobility, and death are evident from all angles.

The theater structure and the altar were only two of the important buildings on the acropolis of Pergamon. Yet, in these two structures and in their decoration, the Hellenistic style comes through. Both the theater and the altar are highly dramatic. The theatre positions the audience at an extremely steep angle with a breathtaking view of the ocean behind the action of the players. The plays enacted there reflected the changing times in their addition of a clever slave. Comedy was topical but unlike Classical Greek comedy, it would not lampoon the ruler.

The images carved in the frieze of the Altar of Zeus are caught in a moment of intense action. It seems as if the wind is blowing the garments around the figures, adding to the drama. The fascination with the moment of death is seen in both free-standing sculptures. Unlike his predecessors, the Gaul who is lying down is seen after the event, the moment before he dies. His image is not about potential. His is an image of contemplation of loss. The standing figure also prepares for death. His idealistic proportions do little to keep him from his fate. The mixture of the real and the ideal is unsettling. He is quite beautiful as he commits the ultimate act of self-reliance.

These public monuments fit neatly into the Hellenistic period. There is virtuosity in the carving. The grouping of bronze statues would have been an indication of the wealth of the city, as well as the pride that Pergamon took in defeating the Gauls, who were feared by nearly everyone in the ancient world. The Greek city in the Persian landscape was in itself a mixture of cultures. The mix of those two cultures can be seen in the podium on which the Altar sits. This mix of styles and cultural values can also be seen when viewing some of the art that was created elsewhere in a world that was rapidly becoming Hellenized.

For a better view of the Gaul, click on the following virtual link:

DYING GAUL AND LUDOVISI GAUL (4:31)

If you have trouble viewing the video above, use this link: https://smarthistory.org/dying-gaul/

Attribution:

“Pergamon.” Boundless Art History. Ancient Greece, The Hellenistic Period.

References:

1. Photo by Hans Schleif, CC BY-SA 3.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pergamon_Modell.jpg

2. Photo by Bernard Gagnon, CC BY-SA 3.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Theatre_of_Pergamon.jpg

3. Photo by Lestat (Jan Mehlich), CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Berlin_-_Pergamonmuseum_-_Altar_01.jpg

4. Photo by Claus Ableiter, CC BY-SA 3.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Altar_de_Pergamo_-_Nereu_e_Oceano.jpg

5. Photo by Gryffindor, Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Gigantomaquia_-_Altar_de_P%C3%A9rgamo.jpg

6. Photo by antmoose, CC BY-SA 2.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dying_gaul.jpg

7. Photo by Jastrow, public domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ludovisi_Gaul_Altemps_Inv8608_n3.jpg

8. Photo by Miguel Hermoso Cuesta, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/ Category:Ludovisi_Gaul# /media/ File: Gálata_Ludovisi_09.JPG