3.4 Egypt-New Kingdom

The New Kingdom of reunified Egypt that began in 1530 BCE saw an era of Egyptian imperialism, changes in the burial practices of pharaohs, and the emergence of a brief period of state-sponsored monotheism under the Pharaoh Akhenaten. In 1530 BCE, the pharaoh who became known as Ahmose the Liberator (Ahmose I) defeated the Hyksos and continued sweeping up along the Eastern Mediterranean. By 1500 BCE, the Egyptian army had also pushed into Nubia southward to the fourth cataract of the Nile River. As pharaohs following Ahmose I continued Egypt’s expansion, the Imperial Egyptian army ran successful campaigns in Palestine and Syria, along the Eastern Mediterranean. The adoption of the Hyksos’ chariot and metal technologies contributed to the Egyptian ability to strengthen its military.

During the New Kingdom, pharaohs and Egyptian elites used the Valley of Kings, see image 3.22, located across the Nile River from Thebes, as their preferred burial site. They desired tombs that were hidden away and safe from thieves looking for treasure. Therefore, instead of pyramids, they favored huge stone tombs built into the mountains of the Valley of the Kings. Nearly all of the burials in the Valley of the Kings were raided, so the fears of the pharaohs were well founded.

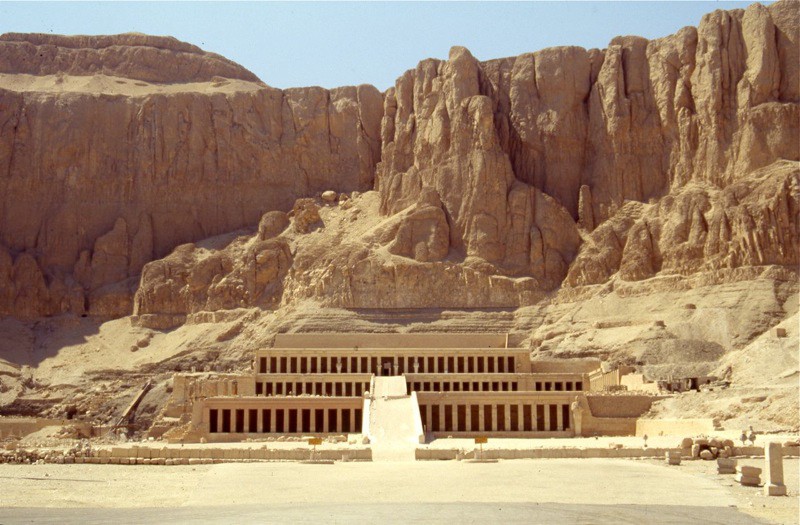

During the Middle and New Kingdoms many of the rulers also built massive temples which were used to worship them in their new roles as gods after their death. The temples were not the same, but many of them have similar characteristics. They had a large gateway, which was called a pylon and a hypostyle hall which was a forest of huge columns to hold up large stone slabs which formed the roof. This post and lintel system created a dark mysterious space that was used by the priests as a place of worship apart from the view of the lower-class citizens.

Hatshepsut, circa 1479-1457 BCE, was the daughter of Thutmose I, granddaughter of Ahmose the Liberator, and married her half-brother Thutmose II. When her husband died, she ruled as regent for her young son. But when he came of age, she refused to relinquish control. The priests crowned her pharaoh and she ruled for twenty years. Over the years artists depicted her with fewer and fewer feminine characteristics, and she dressed in the familiar royal ceremonial clothing befitting a pharaoh. When she was removed from power by her son, many of the images of her reign were destroyed. She altered her name with a masculine ending, was addressed as “His Majesty” and was depicted in the clothing of a king with the pharaonic beard, and the royal sheldyt kilt.

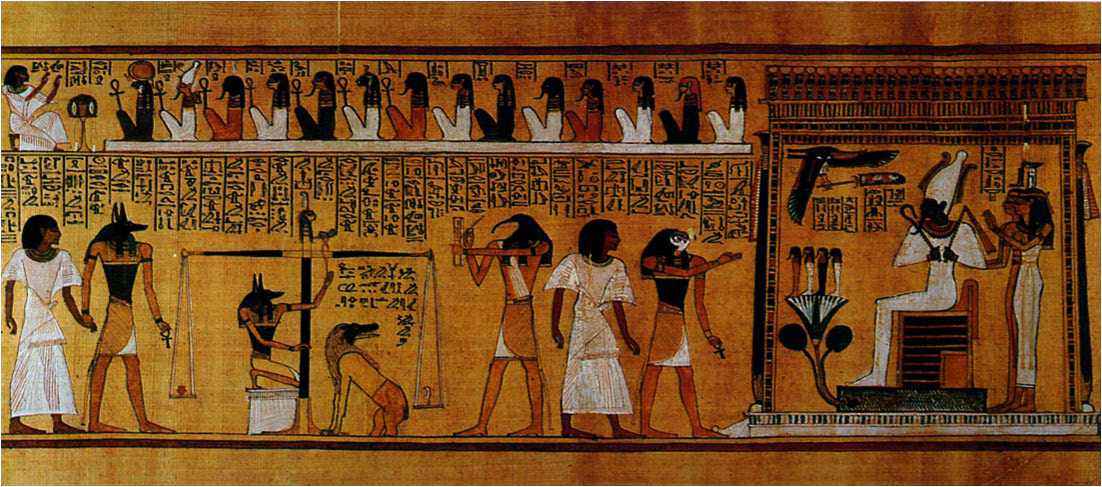

Throughout dynastic Egypt, much continuity existed in religious beliefs, causing scholars to characterize Egyptian society as conservative, meaning that Egyptians shied away from change. In general, Egyptian religious beliefs emphasized unity and harmony. Throughout the dynastic period, Egyptians thought that the soul contained distinct parts. They believed that one part, the ka, was a person’s life force and that it separated from the body after death. The Egyptians carried out their elaborate preservation of mummies and made small tomb statues to house their ka after death. The ba, another part of the soul, was the unique character of the individual, which could move between the worlds of the living and the dead. They believed that after death, if rituals were carried out correctly, their ka and ba would reunite to reanimate their akh, or spirit.

If they observed the proper rituals and successfully passed through Final Judgment (where they recited the 42 “Negative Confessions” and the god Osiris weighed their hearts against a feather), Egyptians believed that their resurrected spirit, their akh, would enter the afterlife. In the afterlife, Egyptians expected to find a place with blue skies, agreeable weather, and familiar objects and people. They also expected to complete many of the everyday tasks, such as farming, and enjoy many of the same recognizable pastimes. Through the centuries, the Egyptians conceptualized the afterlife as a comfortable mirror image of life. One change that occurred over time was the “democratization of the afterlife.” As time progressed through the Middle Kingdom and into the New Kingdom, more and more people aspired to an afterlife. No longer was an afterlife seen as possible for only the pharaoh and the elite of society. Instead, just about all sectors of society expected access, as evident in the increased of funeral texts, like the Book of the Dead. People of varying means would slip papyrus with spells of prayers from the Book of the Dead (or a similar text) into coffins and burial chambers. They intended these spells to help their deceased loved ones make it safely through the underworld into the pleasant afterlife.

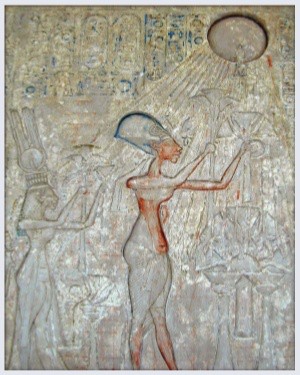

Egyptian art and culture remained stable and unchanging for thousands of years. Drastic change can only be seen in one 25-year period of Egyptian history. We call it the Amarna period. In the 14th century B.C.E. Amenophis IV introduced ideas which modified the religious beliefs that had guided Egyptian philosophy and shaped its institutions since its earliest pharaohs. He was a heretic, and tried to replace the many traditional gods of Egypt with a single Supreme Being, Aton. He changed his name from Amenophis to Akhenaten, (“it pleases Aton”) and moved the capital of Egypt from Thebes to Tell-el- Amarna, from which the Amarna Period takes its name.

Why did Akhenaten introduce these radical changes? Akhenaten was probably trying to break up the power and influence of the long-established priests of Amon-Ra with his reforms. When he took the throne, the priests owned 1/3 or the arable land and controlled 1/5 of the workforce. The Temple of Amen controlled 81,000 slaves and servants, 421,000 head of cattle, 691,000 acres of agricultural land, 83 ships, 46 shipyards, and 63 cities. This wealth was a challenge to the power of the pharaoh. Akhenaten moved to take control of these resources and limit the power of the temple priests. He shut down the temples of the old gods, removed representations of those gods from his city, and even removed the plural word “gods” in favor of his monotheistic references to Amon-Ra. Additionally, by taking on the role of the son of Aten and regulating entry into the afterlife, Akhenaten certainly attempted to reformulate beliefs to emphasize his own importance.

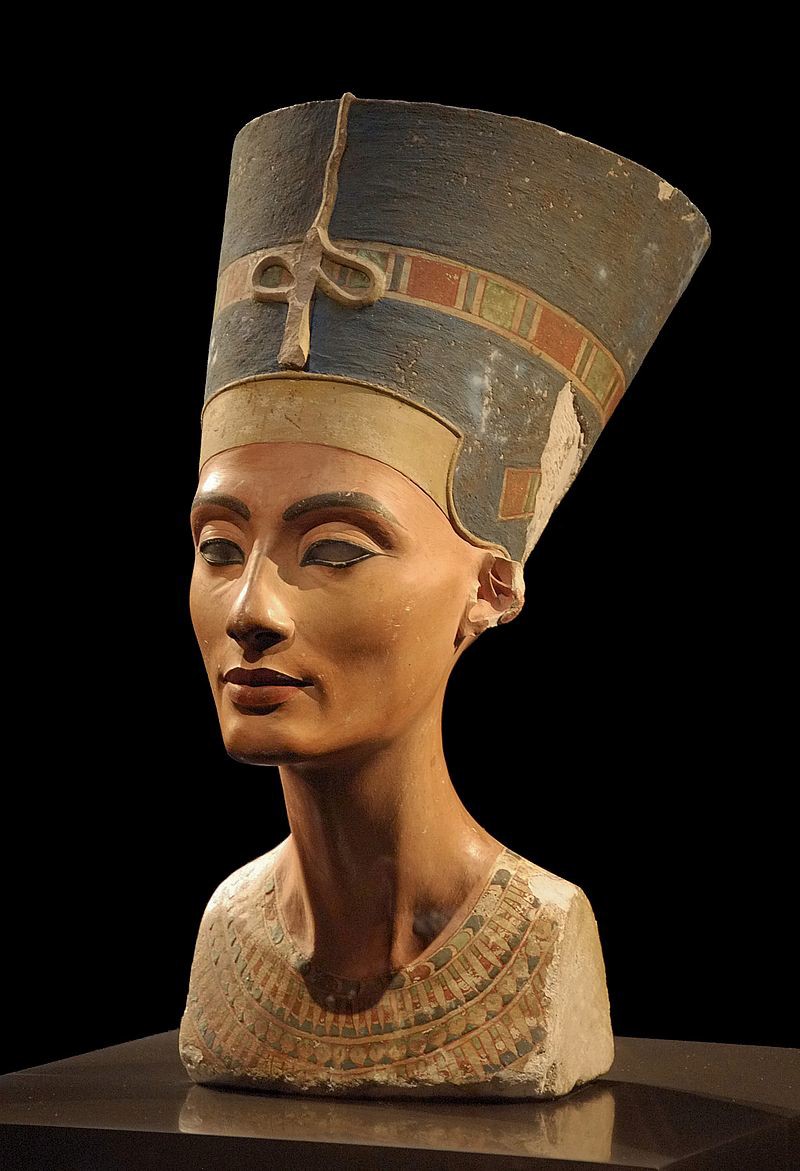

Although Akhenaten’s religious revolution was a failure; his artistic revolution was much more successful. The Amarna period witnessed the most dramatic changes Egyptian art had ever seen, and its influence lingered long after its rulers had been consigned to oblivion by the outraged public. Some say that Akhenaten was directly responsible for the new artistic style. His chief sculptor, a man named Bak, claims that he was taught sculpting by the king himself, in a surviving inscription at Aswan.

The art of the Amarna period breaks radically with Egyptian tradition in its depictions of royalty. These are some of the most important characteristics of the art of this time:

- The king is shown in casual poses, playing with his children, and much of the stiffness of Egyptian art gives way to a new softness and fluidity.

- Curved lines replace the stiff horizontal and vertical lines seen in the rest of Egyptian art.

- The king is depicted on the same scale as other people, indicating a much humbler attitude, and greater interest in naturalism.

- The king’s body is not idealized, but looks rather deformed. Some scholars think Akhenaten may have had Frolic’s syndrome, or some other genetic disorder, but such diseases are difficult to properly diagnose from artwork. Nonetheless, the king has a very elongated face, with wide, curved feminine hips and breasts. Many students mistake him for a woman when they see the surviving sculptures. The feminine traits may be symbolic, to indicate that the king embodied both the male and female. We don’t know.

- Sunken relief is more common in the Amarna period than raised relief.

- It also shows a particular moment in time, rather than the timeless and eternal art of earlier periods.

- Figures are not posed, formal and stiff-looking. Bodies indent the cushions they sit on; they are not fused with the stone. They appear to interact with the real world.

- Figures are much more sensual and there is a greater interest in the female form in particular. Children are depicted, but Akhenaten’s daughters appear as miniature adults. Although very small, they have adult figures and proportions, with breasts and hips.

- Aton enjoys center stage during the Amarna period, pushing the hundreds of other Egyptian gods out of the picture.

Akhenaten’s radical changes were likely troubling for most of the Egyptian population. They had previously found comfort in their access to deities and their regular religious rituals. The worship of Aten as the only Egyptian god did not last more than a couple of decades, floundering after the death of Akhenaten. Pharaohs who ruled from 1323 BCE onward tried not only to erase the religious legacies of the Amarna Period, but also to destroy the capital at Tell el Amarna and remove Akhenaten from the historical record. Archaeologists have not found Akhenaten’s tomb or burial place. Scholars continue a long-standing debate about how this brief period of Egyptian monotheism relates (if at all) to the monotheism of the Israelites. Despite such uncertainties, study of the Amarna period indicates that Egyptians in the fourteenth century BCE saw the fleeting appearance of religious ideology that identified Aten as the singulargod.

Akhenaten died in about 1365 BC, and Tutankhamen’s reign lasted about 9 years, from 1361 to 1352 and he was probably 19 when he died, having taken the throne at age 10. Tutankhamen married his half-sister, Ankhesenamun, but they did not produce an heir. This left the line of succession unclear. Some think the priests of Amon-Ra may have been responsible for his death. Whether or not that is true, the priests quickly re-established their rule after his passing. Because Tutankhamen was a minor ruler from a time Egyptians wanted to forget, he had a small and unimposing tomb. It is only his obscurity that preserved the remarkable contents of his tomb, which are among the most splendid art objects still in existence from ancient Egypt. It’s hard to imagine what an important pharaoh must have taken with him into the afterlife, considering the hundreds of pounds of pure gold lavished on a minor figure like Tutankhamen.

Some of the strongest rulers of the New Kingdom, including Ramses I and Ramses II, came to power after the Amarna Period. These pharaohs expanded Egypt’s centralized administration and its control over foreign territories. However, by the twelfth century BCE,weaker rulers, foreign invasions, and the loss of territory in Nubia and Palestine indicated the imminent collapse of the New Kingdom. In the Late Period that followed (c. 1040 to 332 BCE), the Kingdom of Kush, based in Nubia, invaded and briefly ruled Egypt until the Assyrians conquered Thebes, establishing their own rule over Lower Egypt. Egyptian internal revolts and the conquest by Nubia and the Assyrian Empire left Egypt susceptible to invasion by the Persians and then eventually the 332 BCE invasion of Alexander the Great.

We should discuss Ramses II when we talk about the New Kingdom. He was born at approximately 1300 BCE to his father Seti I and his father’s principle wife, Tuya. Ramses II spent many years studying under his father’s watchful eye. He acted as his father’s deputy in military, religious and administrative actions while he was still a young man. In 1279, when Ramses II was in his mid twenties, Seti died and Ramses II was crowned pharaoh. Ramses II ruled Egypt for over 60 years, until he was 96 years old. He had over 200 wives and concubines and fathered 96 sons and 60 daughters.

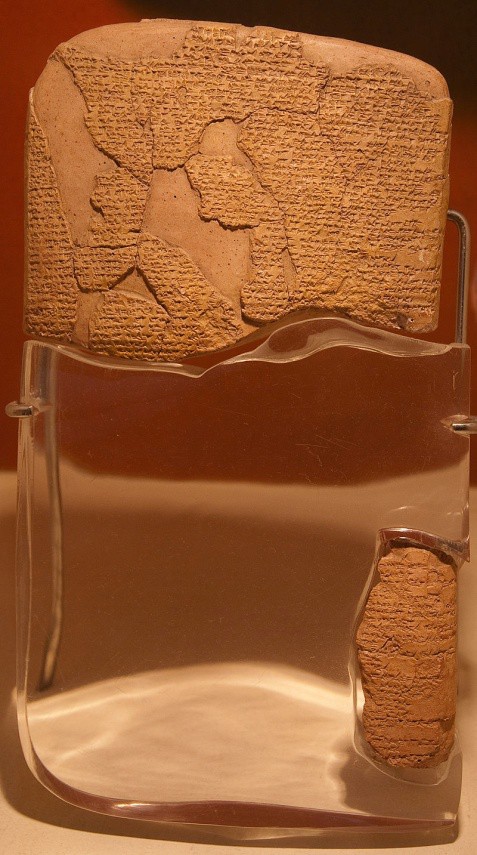

Ramses II is known for defeating the Hittites at the Battle of Kadesh as both armies fought for control of Syria, and signed the world’s first known peace treaty at the end of that war.

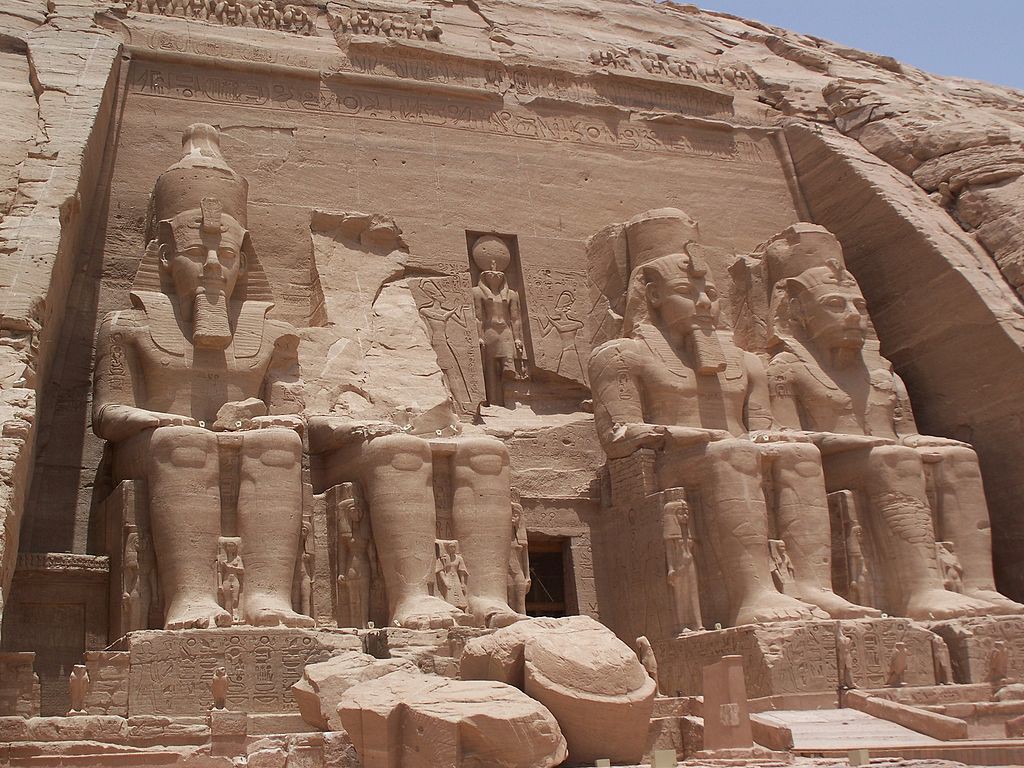

Ramses is known for his massive building projects, including many monuments, cities, and the Abu Simbel complex, which had to be moved to the top of a cliff in 1967, block by block, to allow the Aswan Dam to be built. Note image 3.38 and 3.39 that show the model of the Abu Simbel carvings in their original position which would have been under water when the new Aswan Dam was built, and the new, dry position on top of the cliff after they were moved. The exhibit at the Nubian Museum does an excellent job comparing the placement of the works before and after they were moved.

Attributions:

Berger, Eugene; Israel, George; Miller, Charlotte; Parkinson, Brian; Reeves, Andrew; and Williams, Nadejda, “World History: Cultures, States, and Societies to 1500” (2016). History Open Textbooks. 2.

References:

1. By Francesco Gasparetti CC BY 2.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?sort=relevance&search=valley+of+the+kings&title=Special%3ASearch&profile=advan ced&fulltext=1&advancedSearch-current=%7B%7D&ns0=1&ns6=1&ns12=1&ns14=1&ns100=1&ns106=1#/media/File:Flickr_-_Gaspa_-_Valle_dei_Re,_panorama_(4).jpg

2. Photo by MusikAnimal, CC BY-SA 4.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?search=Hypostyle%20hall&title=Special%3ASearch&fulltext=1&ns0=1&ns6=1&ns12= 1&ns14=1&ns100=1&ns106=1#/media/File:Pillars_of_Great_Hypostyle_Hall_in_Karnak_Luxor_Egypt.JPG

3. Photo by Charlie Phillips, CC BY 2.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Mortuary_Temple_of_Hatshepsut#/media/File:Deserted_temple_of_H atshepsut,_Deir_El_Bahri,_Egypt.jpg

4. Photo by Remih, CC BY-SA 3.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=Special:Search&limit=100&offset=100&profile=default&search=Ha tshepsut&advancedSearch- current={}&ns0=1&ns6=1&ns12=1&ns14=1&ns100=1&ns106=1#/media/File:Hatshepsut_temple15.JPG

5. Metropolitan Museum, Open Access -Public Domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Kneeling_statues_of_Hatshepsut_in_the_United_States#/media/File:L arge_Kneeling_Statue_of_Hatshepsut_MET_21V_CAT092R3.jpg

6. Photo by Kathy J. Hartman.CC-BY-NC-4.0 License.

7. Author: Jean-Pierre Dalbéra, Source: Wikimedia Commons, License: CC BY 2.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:La_salle_dAkhenaton_(1356- 1340_av_J.C.)_(Mus%C3%A9e_du_Caire)_(2076972086).jpg

8. Photo by Gerbil CC SA 3.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Akhenaten,_Nefertiti_and_their_children.jpg

9. By Jean-Pierre Dalbera, CC BY 2.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Statues_of_Akhenaten_in_the_Cairo_Egyptian_Museum#/media/File:La_salle_dAkh enaton_(1356-1340_av_J.C.)_(Mus%C3%A9e_du_Caire)_(2076962048).jpg

10. By Philip Pikart, CC BY-SA 3.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?sort=relevance&search=Bust+of+Nefertiti&title=Special%3ASearch&profile=advance d&fulltext=1&advancedSearch- current=%7B%7D&ns0=1&ns6=1&ns12=1&ns14=1&ns100=1&ns106=1#/media/File:Nofretete_Neues_Museum.jpg

11. Photo by Mark Fischer, CC BY-SA 2.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Funerary_mask_of_Tutankhamun#/media/File:King_Tut_Burial_Mask_ (23785641449).jpg

12. Photo by Kaveh, CC BY-SA 2.5. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Canopic_coffins_of_Tutankhamun#/media/File:Tut_coffinette.jpg

13. Photo by thesupermat CC BY-SA 4.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Stone_vessels_of_Tutankhamun#/media/File:Paris_-_Tout%C3%A2nkhamon,_ le_ Tr%C3%A9sor_du_Pharaon_-_Vase_%C3%A0_onguent_en_calcite_arborant_le_papyrus_et_la_fleur_de_lotus_-_001-edited.jpg

14. By Jerzy Strzelecki, CC BY-NC-SA 3.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Gilded_Wooden_Throne_of_Tutankhamun#/media/File:Tutanchamon_(js)_3detalle.jpg

15. Photo by Roland Unger, CC BY-SA 3.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?search=Battle%20of%20Kadesh&title=Special%3ASearch&fulltext=1&ns 0=1&ns6=1&ns12=1&ns14=1&ns100=1&ns106=1#/media/File:RamesseumPM10.jpg

16. By Photo by locanus, CC BY-3.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?search=Treaty%20of%20Kadesh&title=Special%3ASearch&fulltext=1&ns0=1&ns6=1&ns12=1&ns14=1&ns100=1&ns106=1#/media/File:Table_of_Treaty_of_Kadesh_from_Bo%C4%9Fazk%C3%B6y.jpg

17. By Than217 at English Wikipedia, Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?search=Abu%20Simbel&title=Special%3ASearch&fulltext=1&ns0=1&ns6=1&ns12=1&ns14=1&ns100=1&ns106=1#/media/File:Abu_Simbel_Temple_May_30_2007.jpg

18. Photo taken by Zureks at the Nubian Museum, CC BY-SA 3.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?search=Abu%20Simbel&title=Special%3ASearch&fulltext=1&ns0=1&ns6=1&ns12=1&ns14=1&ns100=1&ns106=1#/media/File:Abu_Simbel_relocation_by_Zureks_2.jpg