11.2 THE CATHEDRAL OF CHARTRES

One of the most magnificent of Gothic cathedrals and the earliest truly Gothic cathedral is located in Chartres a small commercial town about 56 miles southwest of Paris. The original cathedral was built in the 4th century, but when Charles the Bald, grandson of Charlemagne, presented Chartres with “the tunic of the Virgin” the town began to draw huge crowds for the feast of the Virgin. The relic was supposed to have been worn by the Virgin Mary when she gave birth to Christ. In 1194 the existing Romanesque church was almost totally destroyed by a huge fire. The story is told of the monks who quickly grabbed the relic and took it into the crypt beneath the church while the fire raged. After three days they were able to find their way out of the building. The townsfolk believed that the relic and the westwork had been saved by divine design, so they determined to build another church at the same site. The site was on a hill in the city, which, like Acropolis in Athens causes the viewer to look up to it.

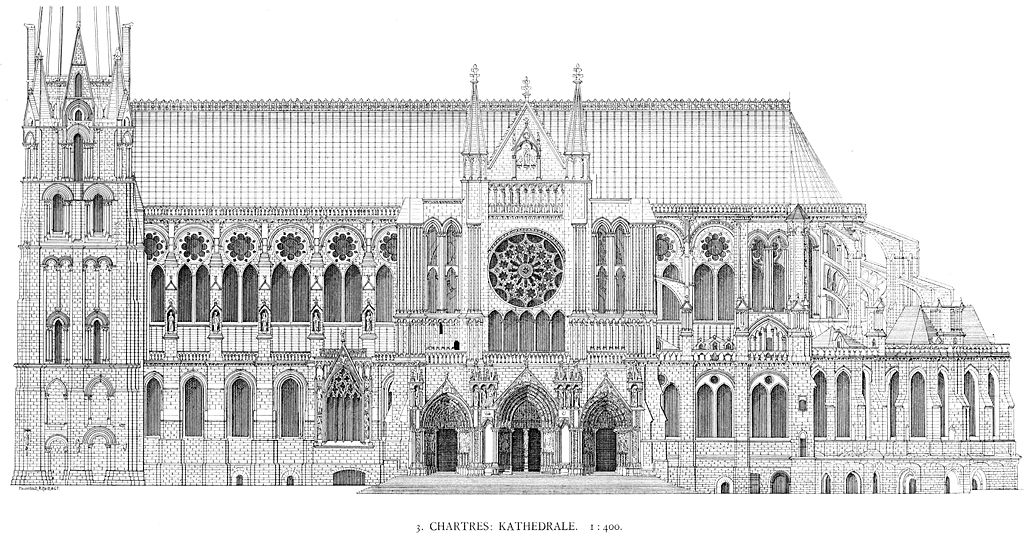

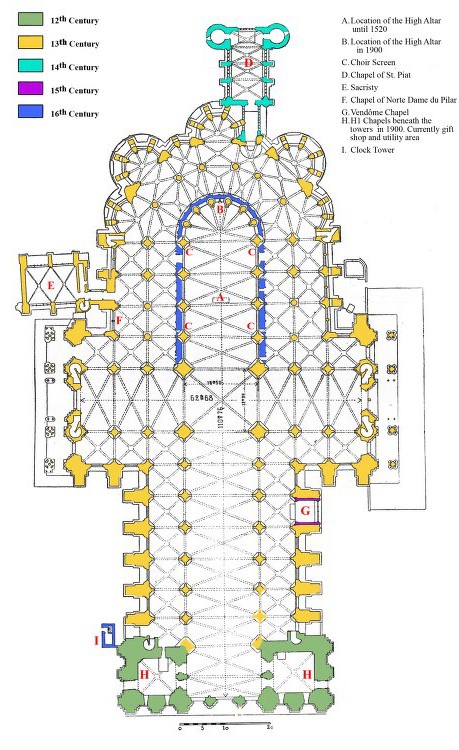

The westwork is nearly all Romanesque with rounded arches, simple entrance doors, and a few pieces of stained glass. The rest of the cathedral was rebuilt in the new Gothic style that architects had seen in St. Denis. So Chartres is the first Gothic cathedral to be built almost entirely as a new Gothic building. The present cathedral was built from the 12th to the 16th century. The two uneven towers are the result of a fire in 1506 that destroyed the north tower. A new “flamboyant” tower (on the left in image 12.21) was built to replace it. Chartres is a typical basilica style cathedral with a transept crossing the nave about midway, a large choir with radiating chapels, and piers along the arcade consisting of a strong central column with four attached slender colonnettes. See image 12.22 with a key to the floor plan in 1900.

Internal Characteristics of Chartres

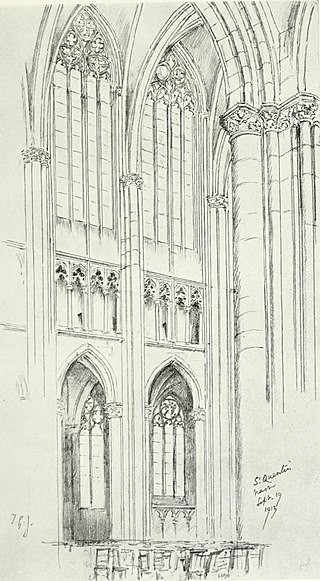

The nave arcade is built with tall pointed arches on the bottom, a narrow triforium in the middle, and a tall clerestory at the top consisting of two lancet windows unified by a rose window at the top. This type of configuration allowed the walls to have more windows and less stone. The pointed arches and the height of the windows draw the eyes upward to the heavens.

The vaults of Chartres are 122 feet high and 53 feet wide. The builders used ribbed vaults to lighten the weight of the stone between the ribs and lessen the thrust pushing down the walls.

The use of pointed arches and point support, as we saw in St. Denis, allowed for more complicated plans where the choir meets the ambulatory, the nave, and each of the radiating chapels. See image 12.26.

The Cathedral of Chartres has more than 2,000 windows that add up to 7 acres of glass. Stained glass of the 12th century was a very time consuming process. Windows were made by the glass makers’ guild and paid for by various groups or individuals. We used to think that the images of cobblers, tanners, and shoemakers were evidence that those guilds donated the windows, but the exorbitant cost of the windows likely prohibited that.

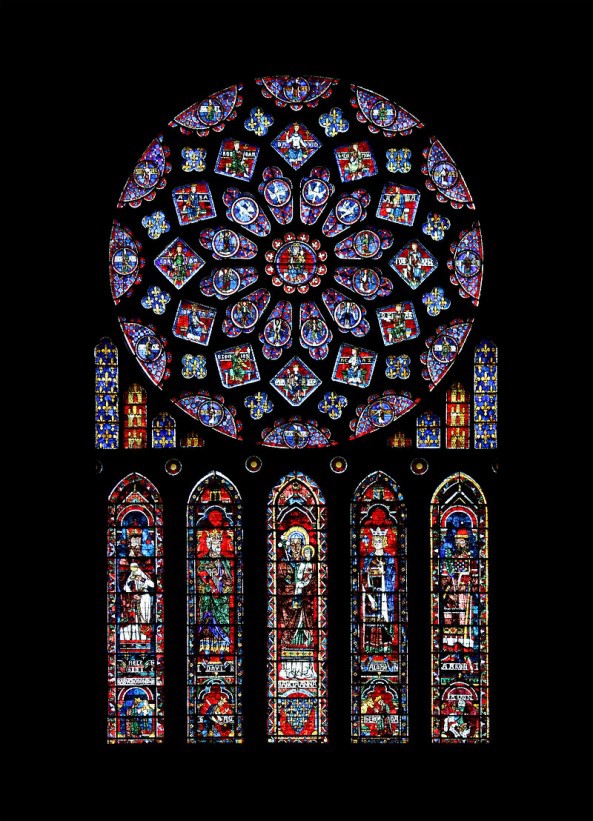

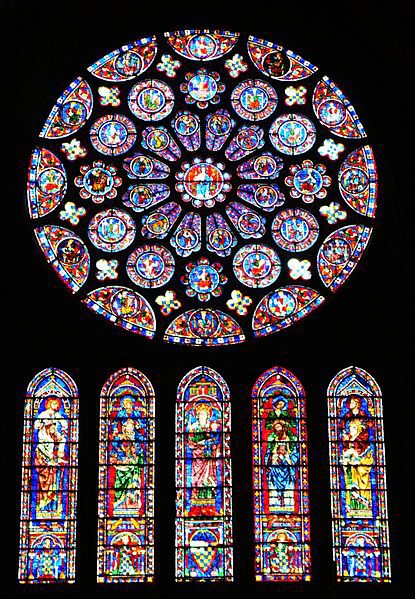

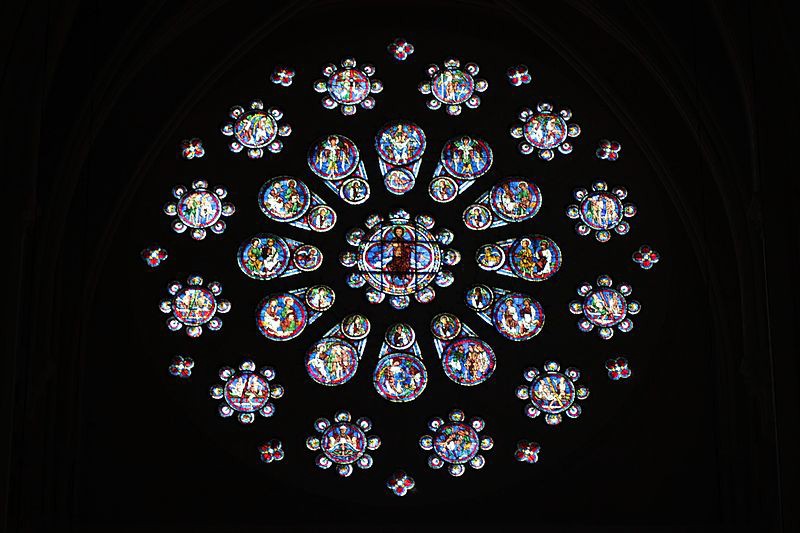

Patrons of the cathedral were princes and kings and they often donated windows. For instance, the North Rose was made in 1223-1226 was donated by Blanche of Castille who was Spanish. See image 12.29 and note the castles included in the lower corners surrounding the rose. These are a combination of Spanish and French royal castles. Not to be outdone, Blanche’s rival, the family of the Count of Dreux, see image 12.30, also donated a rose window exactly opposite her rose window on the south wall. So now they will stare at each other across the transept forever.

Rose windows are supported by stone tracery which allows the light to enter through intricate patterns. Compare the interior and exterior views of the West Rose in images 12.31 and 12.32.

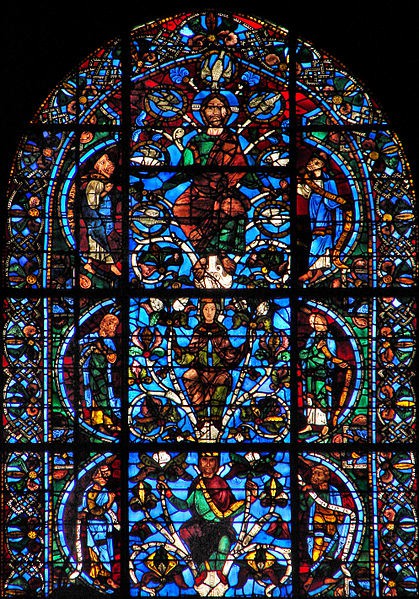

Most of the windows of Chartres were installed in the early 13th century. They tell stories of the Old and New Testament to acquaint the illiterate peasants with the scriptures and were literally glass Bibles. For instance, the Tree of Jesse explained the genealogy of Christ. On the bottom we see Jesse, lying on a couch, with a large tree growing from his body. Each succeeding branch of the tree is another generation of the family tree, until we see Mary and then Christ at the top. See image 12.33 and 12.34.

Many of the stories and parables from the Bible are included in the windows. Image 11.35 and 11.36 show the story of the Good Samaritan and the Marriage of Cana.

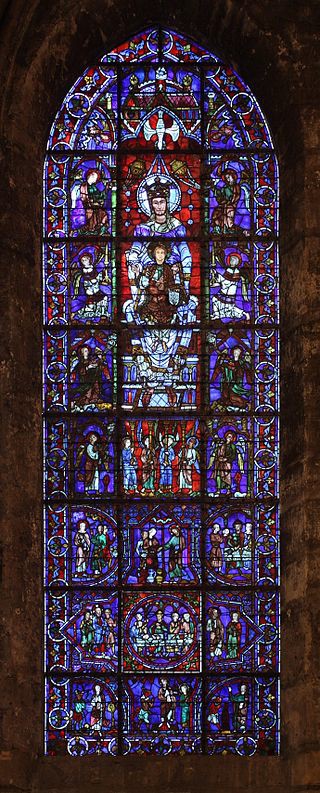

The oldest window in Chartres is the Notre Dame de la Belle Verriere which survived the fire of 1194 with minimal damage. It was moved to the south end of the building when it was rebuilt and was a symbol to the people of Chartres that the Virgin Mary had protected it and therefore wanted the church to be rebuilt. It has 24 sections that tell the story of the temptation of Christ, his first miracle at Cana, and several views of Mary and Christ enthroned. See image 11.37 and image 11.38

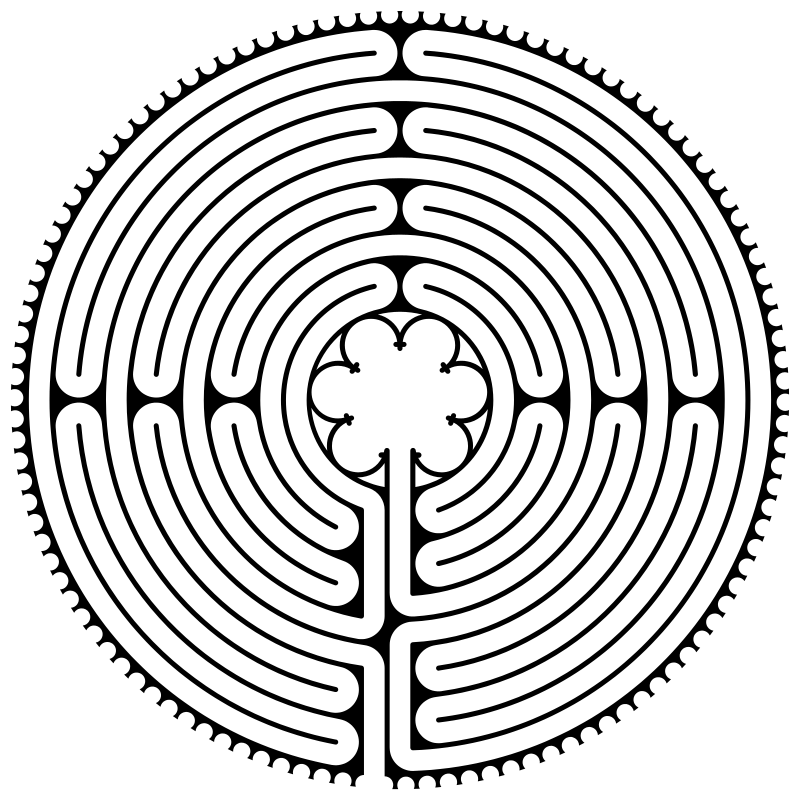

One of the great treasures of Chartres is the labyrinth built into the floor of the nave. The oldest existing labyrinth in the world is in Sardinia and was probably built about 2500 CE, but many medieval churches added labyrinths to their areas of worship. The circumference of the labyrinth at Chartres is just over 42 feet, and the path is 16’’ wide. A pilgrim walking the path travels 861.5 feet and it was the largest labyrinth made in the Middle Ages. Labyrinths are replete with symbolism. Today, as in the twelfth century, visitors walk the eleven concentric circles toward the six petaled rosette in the center, which could symbolize the six days of creation. The rosette may be a symbol of Mary, but it could also relate to Aphrodite and Isis. The 28 lunation’s on the outside of each quadrant relate to the cycles of the moon. It is likely that the labyrinth was inspired by the Knights Templar and the free masons, who were involved in the building of the cathedral. The path consists of three parts: walking in to the labyrinth is a time to let go and purge oneself, a release. Arriving in the center is a time to receive, to reconnect with your spiritual self, to find illumination and clarity. The walk out of the labyrinth is a time to resolve to return a better person and to be unified with God and self.

From the 17th century on, the labyrinth was covered with chairs in an effort to hide it. Some thought that it was associated with the pagans and wanted to pretend it was not there. Many other cathedrals that had labyrinths removed them from their naves during this time. The depth of the black stone that was used to create this labyrinth was installed so deep beneath the nave that removing it would have damaged the floor, so it was determined to cover it with chairs instead. It was only in the 1990s that a movement was begun to allow pilgrims to again walk its path.23

External Characteristics of Chartres Cathedral

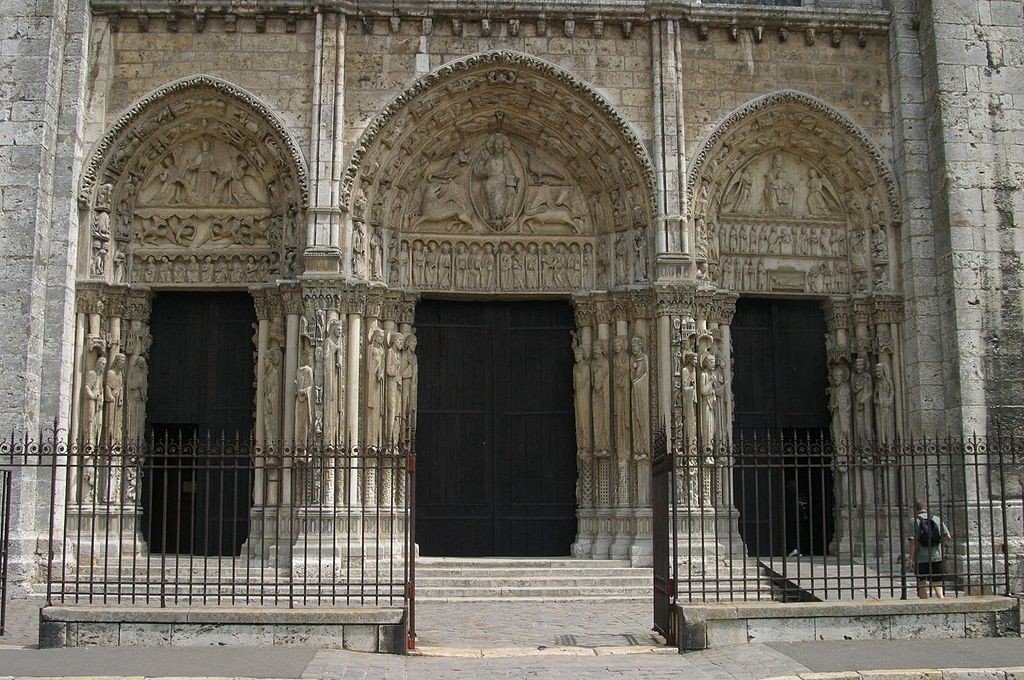

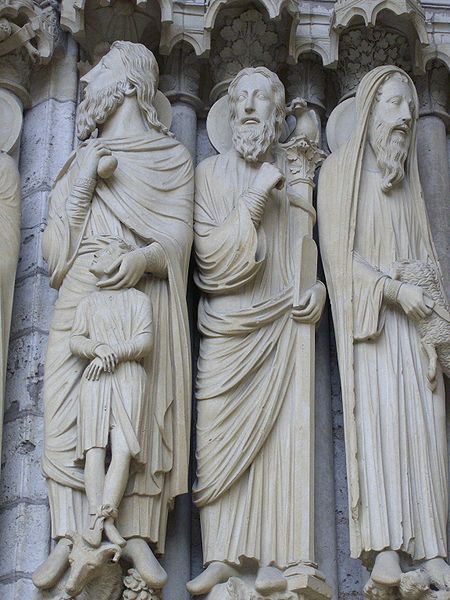

As was the case with Gothic cathedrals, Chartres had a westwork. See image 12.21. However, remember that there is a small section of the westwork at Chartres that retains some Romanesque features because it was leftover from the before the 1194 fire. The lancet windows are more rounded than pointed, the doors are nearly flat, and the ornamentation is fairly simple. As the decades passed the builders of Chartres added more complicated sculpture courses on the porches to the entrance doors on the north and south elevations. Sculpture became more natural, more human, and less attached to the pillars or the walls. Compare image 12.41 and 12.42 to see the changes that occurred in exterior sculpture. Notice that the Jamb columns of the west façade, commonly called the Royal portal, are abnormally tall, straight, and thin and their feet point down, much like the feet of the characters in Byzantine paintings. Note the more rounded and fleshy forms of the martyrs of the south portal. The statue of St. Theodore on the left of the group has a slight contrapposto weight shift and his right knee bends as though he is ready to step down and leave on a crusade. The folds of the hem of his tunic are deep and represent real fabric that could move in the breeze. The fabric worn by the other royalty is static and almost sticks to the bodies of the wearers.

Flying buttresses were an integral part of the support system of the cathedral of Chartres. Circular flying buttresses were added to the walls on the exterior of the nave. See image 12.43. Compare these nave buttresses to the thinner and longer buttresses built to support the walls of the choir and ambulatory on the east end. By the time the builders began working on the east end of the cathedral, newer, thinner buttressing was being tested and proven save in other places, so they built Chartres with the thinner walls and the more delicate buttresses. These were attached to the walls at the point where the greatest thrust began pushing downward protecting the walls from collapse, and adding a beautiful element to the exterior of the building.

Due to their Romanesque origin, the portals on the west end of the cathedral were shallow, but they tell a story that is one of the most unified in all of the Gothic cathedrals. The sculptures found in each of the three portals tell the story of Christ. On the left is Christ before he was born with angels in the lintel at the bottom and the earthly prophets below, not able to communicate well with Christ. In the door on the right is the story of Mary and her role in bringing Christ to earth. We see the annunciation to Mary that she is expecting a child, Mary and her cousin Elizabeth talking about the coming birth of Jesus and John, Mary in the stable with the swaddled child above her, and Mary with the Christ child sitting on her lap.

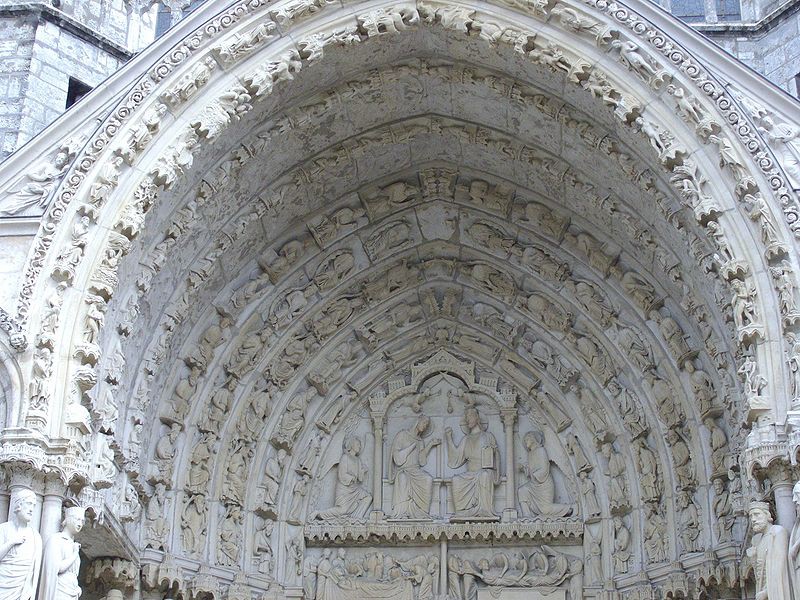

She is now the throne of wisdom, and he is wisdom. See image 11.45 which is a detail of the central portal and its tympanum above it which show Christ at the Second Coming, surrounded by his apostles Matthew, Mark, Luke and John and the twelve apostles in the lintel below. See figure 11.41 for a detail of the kings and queens on the jamb columns below these doors.

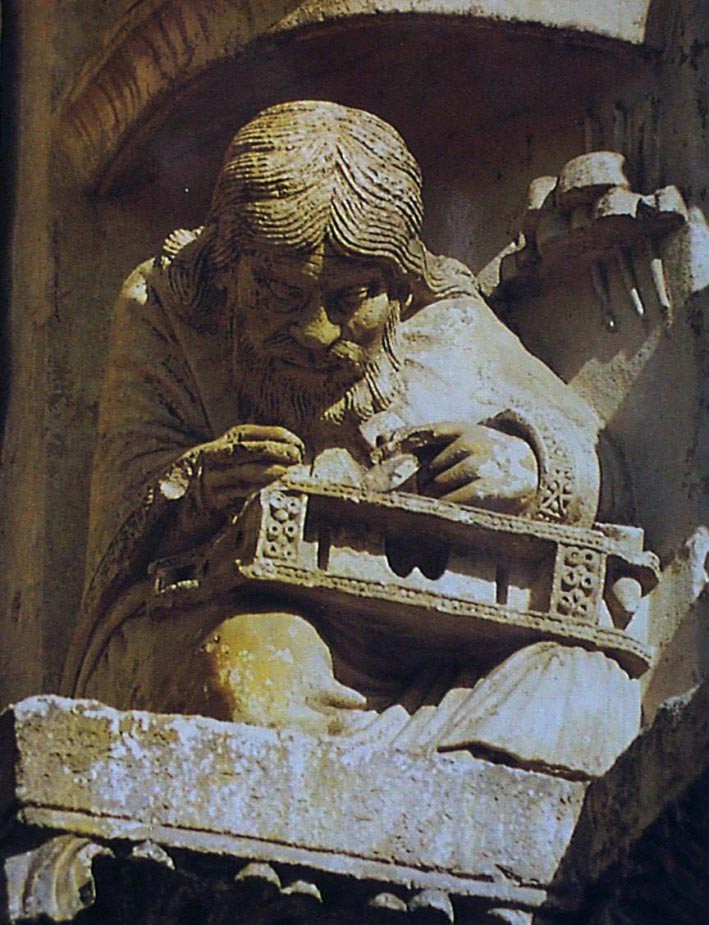

The right bay of the west portal shows each of the liberal arts personified as a female character and a person who excelled in that art at work. See Aristotle in 12.48 and Pythagoras in 11.49. If you look you can see: Pythagoras for music, Boethius for arithmetic, Cicero for rhetoric, Archimedes or Euclid for geometry, Aristotle for philosophy, Ptolemy for astronomy, and Donatus for grammar. These seven liberal arts were the topics studied in the famous Cathedral of Chartres.

By contrast, look at the north portal at Chartres. Notice how deep the carving is and how many layers there are in the archivolts. There are two or three rows of archivolts in the doors of the west façade, and there are eight layers in the archivolts of the north portal. These deep passages are filled with stories that the visitor would have “read” as they passed into the cathedral.

Image 11.52 shows a close detail of the prophet Abraham holding his son Isaac and clutching the sacrificial knife in his right hand. Isaac is bound hand and foot, and Abraham stands on the ram that will become the sacrifice once the father has shown his willingness to obey God’s commandment to offer his son. Abraham looks upward to where the voice of God warns him not to harm the boy, and he gently cradles his son’s chin in a protective, fatherly gesture.

In addition to the role the cathedral played in religious life, it was also the center of economic and political life. Within the walls of the cathedral on any given market day it was possible to find money changers, merchants selling wine, meat, fuel, or cloth. Of course the church charged a tax to those who sold there, but the both parties benefited from the arrangement. The cathedral was a place to nurse the sick and a place where a traveler could find shelter from the sun and the storms. The floor is slightly slanted to allow water to be used to wash away the refuse. Even though this was a cathedral, it was also a pilgrimage church because of the tunic of the Virgin. So the additional doors added to the north and south transept allowed foot traffic to pass through easily. The nave was also used for political events, town meetings, musical performance, and trials. In short, a Gothic cathedral afforded space to conduct all of the business a town might have. Chartres was the first fully Gothic cathedral built in the new style, and just as visitors had “copied” the innovations at St. Denis, those who came to Chartres learned new things and took them home to their cathedrals that were being built.

Merchants would also set up booths outside, on the warmer south side of the cathedral, just as they do today for the Christmas markets! The porch on this side is considerably wider; the courts of Justice and morality/mystery plays were performed outside. Imagine someone placed on trial standing in this place, with the saints who died for the faith directly overhead. We can imagine swearing to tell the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth. We would not be holding our hands on a Bible but pointing to those figures that are “present” with us!

You may also enjoy the following links to additional media information about Chartres Cathedral:

Attribution:

Berger, Eugene; Israel, George; Miller, Charlotte; Parkinson, Brian; Reeves, Andrew; and Williams, Nadejda, “World History: Cultures, States, and Societies to 1500” (2016). History Open Textbooks.

References:

1. Public domain. http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Chartres_cathedral_2850.jpg

2. Photo by Kathleen J. Hartman, CC BY-NC-4.0 License.

3. Photo by MathKnight, CC BY-SA 3.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Chartres-Cathedral.jpg

4. Drawing by G. Dehio, 1932, Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:ChartresSouthDehioVonBezold.jpg

5. Photo by Roby-commonswiki. CC BY-SA 2.5. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:20050921CathChartresB.jpg

6. Anonymous, Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Chartres-Cathedral-Floor_plan_1900.jpeg

7. Jackson, Thomas Graham, Sir, 1915, Gothic architecture in France, England and Italy.Flickr’s The Commons, no known restrictions. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Gothic_architecture_in_France,_ England,_and_ Italy_(1915)_ (14778546661).jpg

8. BT, from German Wikipedia-Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Triforium_Chartres.jpg

9. Photo by Andreas F. Borchert, CC BY-SA 4.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Chartres_Cathedral_Ambulatory_Vault_2007_08_31.jpg

10. Andreas F. Bouchart, CC BY-SA 4.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File: Chartres_Cathedral_South_ Aisle_View _into_Nave_2007_08_31.jpg

11. Photo by MMensler CC BY-SA 3.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Chartres_-_Cath%C3%A9drale_ (2012.01) _03.jpg

12. Photo by JBThomas4, CC BY-SA 4.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File: Chartres_Bay_44_ Good_Samaritan_ Panel_02.jpg

13. Photo by Guillaume Piolle. Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Chartres_-_cath%C3%A9drale_-_rosace_nord.jpg

14. Loic LLH, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File: Cath% C3%A9drale_de_Chartres_-_Vitrail_Transept_Sud.jpg

15. Photo by Guillaume Piolle, CC BY 3.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cath%C3%A9drale_de_Chartres_-_rosace_ouest,_ext%C3%A9rieur.JPG

16. Photo by Micheletb, Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Vitrail_Chartres-rosace_143.jpg

17. Photo by Micheletb, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Chartres_49_-001.jpg

18. Photo by Vassil, Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Vitrail_Chartres_210209_18_brighter.jpg

19. Photo by JBThomas4, CC BY-SA 4.0– South aisle bay 044. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File: Christ_telling _the_Good_Samaritan_parable_to_a_couple_Pharisees.jpg

20. Photo by Vassil. Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Vitrail_Chartres_210209_07.jpg

21. Photo by Guillaume Piolle, public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Chartres_-_cath%C3%A9drale_-_ND_de_la_belle_verri%C3%A8re.JPG

22. Photo by Vassil, Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Vitrail_Chartres_Notre-Dame_210209_1.jpg

23. https://video.search.yahoo.com/yhs/search;_ylt=AwrWnXE7Z9Vd7i0ANAgPxQt.;_ylu=X3oDMTByZDNzZTI1BGNvbG8DZ3ExBHBvcwMyBHZ0aWQDBHNlYwNzYw–?p=labyrinth+at+chartres+cathedral&fr=yhs-symantec- ext_onb&hspart=symantec&hsimp=yhs-ext_onb#id=11&vid=d021b4e25fda3cc0d907b83902c2d029&action=view

24. Photo by Marcimarc- Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Labyrinthchartres.jpg

25. Photo by Thurmanuky alur CC BY-SA 3.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:ChartresApproximation.svg

26. Photo by Cancre, CC BY_SA 2.5. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cenral_tympanum_Chartres.jpg

27. Photo by TTaylor CC BY-SA 3.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File: Chartres_cathedral_023_ martyrs_S_ TTaylor.JPG

28. Photo by Florestan, CC BY 3.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Chartres_-_cath%C3%A9drale_-_arcs- boutants_de_la_nef.JPG

29. Photo by Kristine Betts, CC BY-NC-4.0 License.

30. Photo by Nina-no, CC By 2.5. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Chartres.jpg

31. Guillaume Piolle CC BY 3.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Chartres_-_portail_royal,_tympan_central.jpg

32. Photo by Fab5669 CC BY-SA 4.0 https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Chartres_-_cath%C3%A9drale,_ext%C3%A9rieur_(37).jpg

33. Photo by Wellcomeimages.org, CC BY 4.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Aristotle,_stone_carving,_Chartres_Cathedral_Wellcome_M0008873.jpg

34. Photo by Jean-Louis Lascoux, public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pythagore-chartres.jpg

35. Photo by TTaylor, Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File: Chartres_cathedral_porch _of_BVM_N_ TTaylor.JPG

36. Photo by Harmonia Amanda, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported. https://commons.wikimedia.org /wiki/File:Cathedrale_nd_chartres_nord017.jpg

37. Photo by Harmonia Amanda, GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2. https://commons.wikimedia.org /wiki/File: Cathedrale_nd_chartres_nord043.jpg