11.1 INTRODUCTION TO THE GOTHIC AGE

The eleventh century would see the beginnings of Western Europe’s re-urbanization. Compared to the cities of the Mediterranean such as Athens, Northern Europe was unpopulated and provincial. Few large cities existed in the area. In those lands that had been part of the Western Roman Empire, city walls often remained, even if these cities had largely emptied of people. During the chaos and mayhem of the tenth and eleventh centuries, people often gathered in walled settlements for protection. Many of these old walled cities thus came to be re-occupied.

One reason for the growth of towns was a revival of trade in the eleventh century. This revival can be traced to several causes. In the first place, Europe’s knights, as a warrior aristocracy, had a strong demand for luxury goods, both locally manufactured products and imported goods such as silks and spices from Asia. Bishops, the great lords of the Church, had a similar demand. They sought olive oil and spices from the East as well as wax, amber, fur and timber from the north. As such, markets grew up in the vicinity of castles and thus caused the formation of towns that served as market centers, while cathedral cities also saw a growth of population.

Further south, in the Mediterranean, frequent raids by pirates (most of whom were Arab Muslims from North Africa) had forced the coastal cities of Italy to build effective navies. One of the chief of these cities was Venice, a city in the swamps and lagoons of northeastern Italy. Over the eleventh century, the city (formerly under Byzantine rule but now independent) had built up a navy that had cleared the Adriatic Sea of pirates and established itself as a nexus of trade between Constantinople and the rest of Western Europe. Likewise, on the western side of Italy, the cities of Genoa and Pisa had both built navies from what had been modest fishing fleets and seized the strongholds of Muslim pirates in the islands of Corsica and Sardinia. This clearing of pirates from the Mediterranean led to an increase in maritime trade and allowed the renewed growth of the old Roman towns that had in many cases remained since the fall of the Western Empire. The cities of Genoa and Venice were able to prosper because they stood at the northernmost points of the Mediterranean, the farthest that goods could be moved by water (always cheaper than overland transport in pre-modern times) before going over land to points further north.

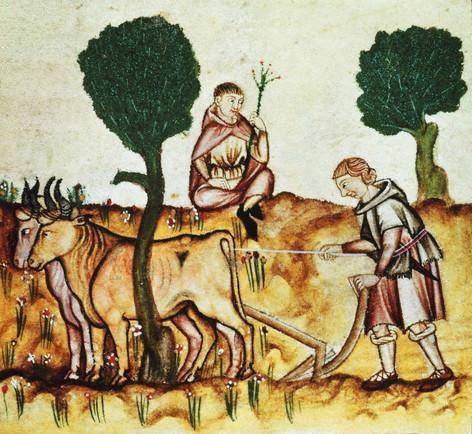

The people living and working in towns came to be known as the bourgeois, or middle class. These were called a middle class because they were neither peasant farmers nor nobles, but rather a social rank between the two. Kings and other nobles would frequently give towns the right to self-government, often in exchange for a hefty payment. A self- governing town was often known as a commune. Eleventh-century Europe’s economy was primarily agricultural. The eleventh and twelfth centuries saw a massive expansion of agricultural output in the northern regions of Europe, which led to a corresponding growth in the economy and the population. The same improvement in iron technology that allowed the equipping of armored knights led to more iron tools: axes allowed famers to clear forests and cultivate more land, and the iron share of a heavy plow allowed farmers to plow deeper into the thick soil of Western Europe.

In addition, farmers gradually moved to a so-called three field system of agriculture: fields would have one third planted in cereal crops, one third to crops such as legumes (which increase fertility in soil), and a third left uncultivated either to serve as grazing land for livestock or simply rebuild its nutrients by lying unused. More iron tools and new agricultural techniques caused yields to rise from 3:1 to nearly 8:1 and in some fertile regions even higher. Another factor in the rise of agricultural yields was Europe’s climate, which was becoming warmer in the eleventh, twelfth, and thirteenth centuries. As a result of both climate change and new agricultural tools and techniques, food supplies increased so that Western Europe would go through the majority of the twelfth century without experiencing a major famine.

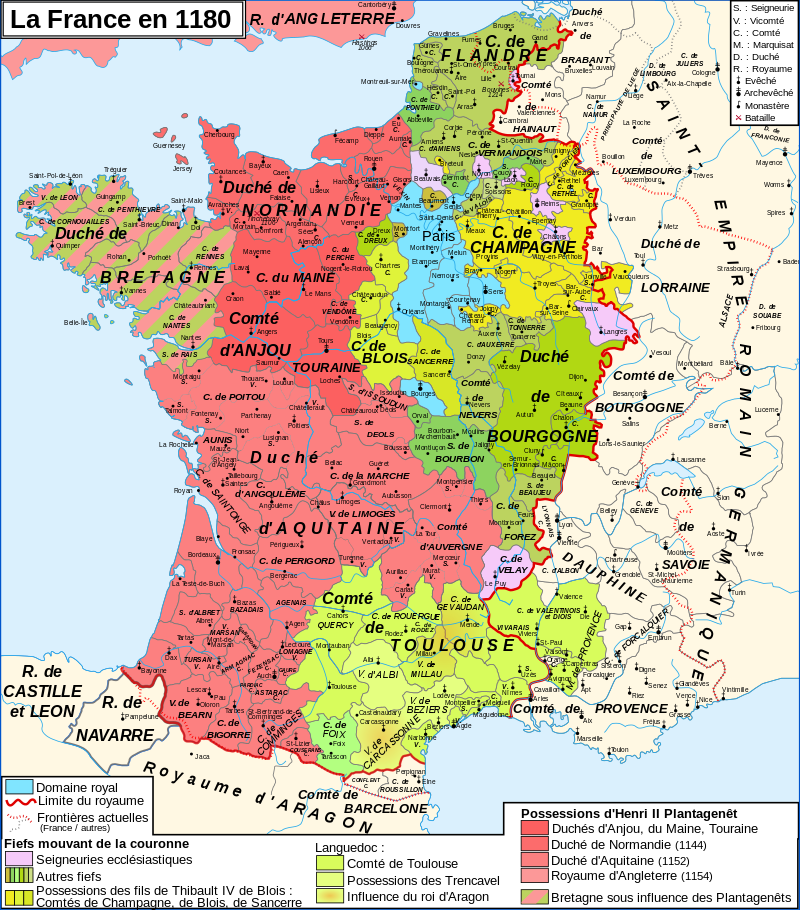

In the years between 1203 and 1214, the French King, Philip Augustus managed to dispossess the English king of almost all of his territory held in France. He was also increasingly successful in using a set of recognized laws to enhance his legitimacy. He made sure that he had a strong legal case drawn up by expert lawyers before he dispossessed England’s King John. Likewise, he created a royal court that was a court of final appeal—and that meant that, even in parts of the kingdom where great lords exercised their own justice, the king had increasing authority. As the Capetian kings gained stronger control over French territories a more sophisticated and accurate royal budget also developed.

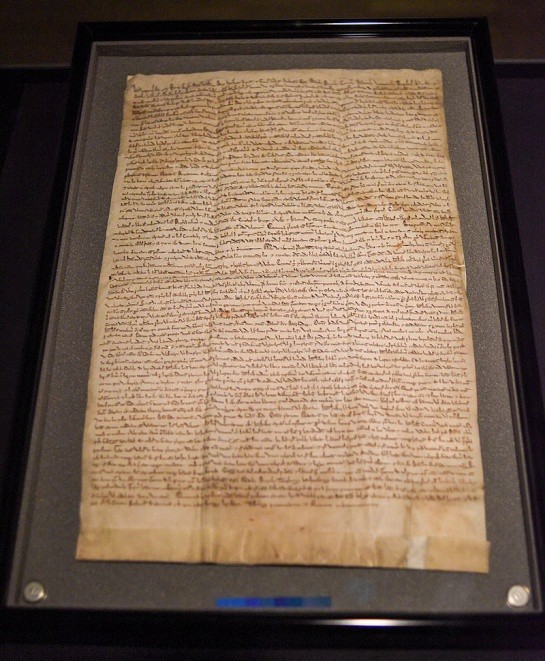

When England’s King John (r. 1199 – 1216) lost to Philip Augustus, his outraged nobles rebelled, resulting in a civil war from 1215 to 1217. One temporary treaty of this civil war, a treaty known as Magna Carta (signed in 1215), would have a much further-reaching impact than anyone who had drafted it could have foreseen. One particular provision of Magna Carta was that if the king wanted to raise new taxes on the people of England, then he needed to get the consent of the community of the realm by convening a council. The convening of such councils, known as parliaments, would come to be systematized over the course of the thirteenth century, until, by the reign of Edward I (r. 1272 – 1307), they would have representatives from most regions of England and would vote on whether to grant taxes to the king. The Magna Carta was a landmark instrument that influenced states and governments for centuries. It was the basis of law and the standard to which governments and princes were held.

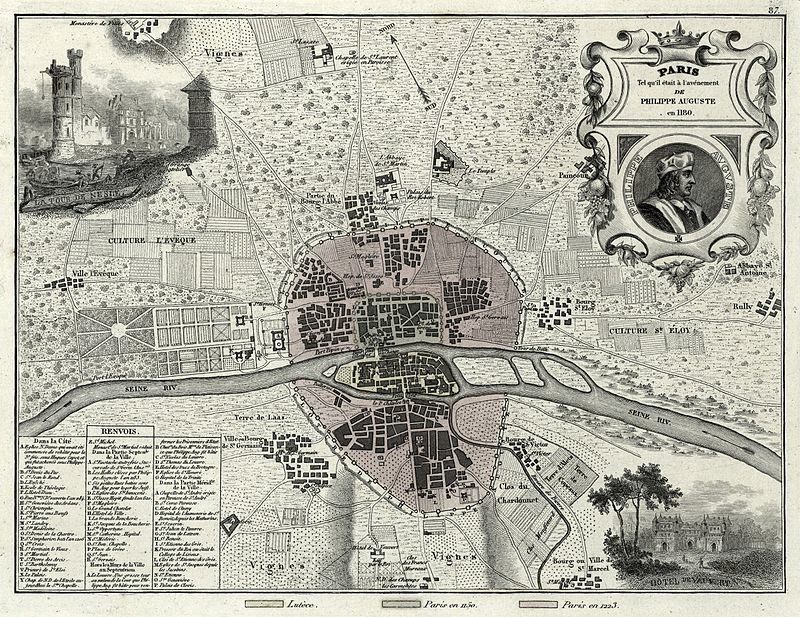

Toward the end of the twelfth century, Philip Augustus, as king of France, began promoting Paris as the capital city. He paved streets and enclosed it with protective walls. In many areas towns began to grow and take on more importance as social units. The Ile-de-France area, with Paris as its center, was the royal domain under direct control of the French kings. The rest of France was still under the dominion of various feudal lords. By heredity, marriage, conquest, and purchase, the Ile-de-France had grown into the nucleus of the future French nation. It was about 100 miles across and included the cathedral towns of Amiens, Beauvais, Rheims, Bourges, Rouen and Chartres.

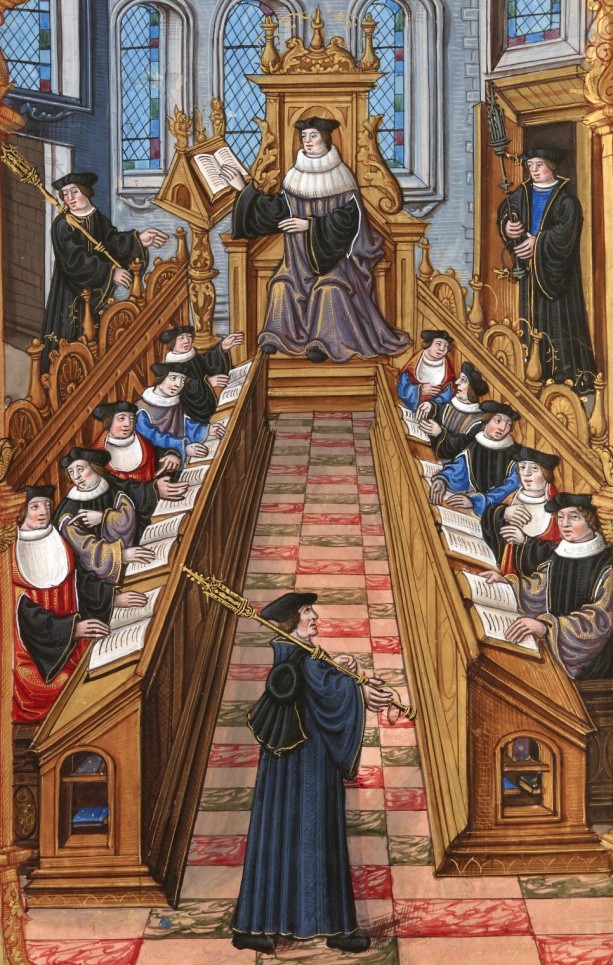

In 1150 a major university grew around the Cathedral of Notre Dame in Paris and it attracted well known teachers such as Abelard, Thomas Aquinas and Bonaventura. Jacques de Vitry, (c. 1170–1240) wrote extensively about the immoral life led by students at the university in Paris. Most of them were very young, were away from home for the first time, and were without supervision. He accused them of lewd behavior, neglecting their studies, and wasting their time.8 The great thinkers that taught in the university at Paris were changing the way Europeans thought and learned.

We generally call the movement to reconcile Christian theology with human reason through the use of logic scholasticism. As more and more works of ancient Greek and Muslim philosophy became available to Western European Christians, the question of how to understand the world acquired more urgency. The philosophers of the ancient Greek and Muslim worlds were known to have produced much useful knowledge. But they were not Christians. How were Christians to understand the world? Should they look for divine revelation as it appeared in the Bible? Or should they find it through the human reason of philosophers? These questions are reminiscent of similar questions taking place in the Islamic world, when thinkers such as al-Ghazali questioned how useful the tools of logic and philosophy were in understanding the Quran.

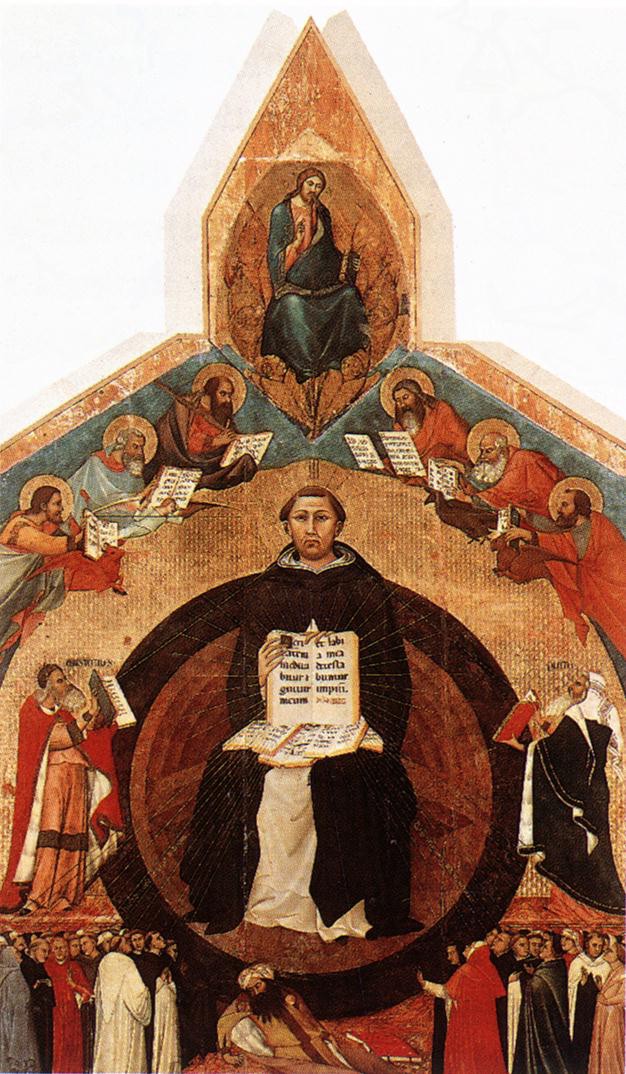

This controversy had raged since at least the twelfth century, when certain devout monks had said, “Whoever seeks to make Aristotle a Christian makes himself a heretic.” Out of this controversy, medieval Europe produced its greatest thinker, St. Thomas Aquinas (1224 – 1274). St. Thomas was a Dominican friar. Friars were those churchmen who, like monks, took vows of chastity, poverty, and obedience. Instead of living in isolated monasteries, though, friars spent much of their time preaching to laypeople in Europe’s growing towns and cities. These friars, whose two major groups were the Franciscans and Dominicans, had schools in most major universities of Western Europe by the early thirteenth century.

Aquinas, a philosopher in the Dominican school of the University of Paris, had argued that human reason and divine revelation were in perfect harmony. He did so based on the techniques of the disputed question. He would raise a point, raise its objection, then provide an answer, and this answer would always be based on a logical argument. Aquinas was only part of a larger movement in the universities of Western Europe. See image 11.9.

Under the peaceful reign of the Capetian Kings, artists crystallized medieval architecture into what we call the Gothic style. Generally the Gothic period is considered to be between 1150 and 1450, although in some areas it began later and lasted until the 1650’s. The term Gothic has nothing to do with the Goths. Italian writers of the 15th and 16th centuries called art of the Middle Ages “maniera die Goti” because they considered all art from the fall of Rome to their own time as crude and barbaric or “Gothic”. Scholars of the 18th and 19th centuries saw an anti-classical style expressive of native genius, hence the change from derogatory reference to one of respect.

The period not only saw successes in the field of speculative philosophy and theology, but also in the practical application of science. The master masons who designed Western Europe’s castles and cathedral churches built hundreds of soaring cathedrals that would be the tallest buildings in Europe until the nineteenth century. These cathedrals were in many ways made possible by the prosperity of Europe’s towns, whose governing councils often financed the construction of these magnificent churches. Within a single generation Gothic cathedrals rose in St. Denis, Chartres, Paris, Laon, Noyon, and Canterbury under the patronage of kings, nobles and the urban middle class. The Gothic cathedral was the center of the medieval town. Cathedral is a term used to denote the seat, or throne of a bishop. So a cathedral has more prestige than a simple church or chapel. Whereas a monastery church may rise from an empty plain or on top of a secluded hill, the Gothic cathedral is built to soar above the rooftops and gables of a city. Often houses and businesses were built against the walls of the cathedral itself. Cities vied for prestige as they sought to produce bigger and grander cathedrals than their neighbors.

Societal changes occurred spurred the growth of large cathedrals in cities all over Europe, but especially in France. Patronage moved to lay and ecclesiastical courts. Wealth moved from landed nobility to manufacturers and merchants in the city. Community pride as well as growing wealth allowed Gothic cities to cooperate in the erection of these soaring stone buildings.

To begin a discussion of what makes a cathedral “gothic”, let’s look at the first building that has all of the basic characteristics: That distinction belongs to the Cathedral of St. Denis which is in the suburbs of Paris.

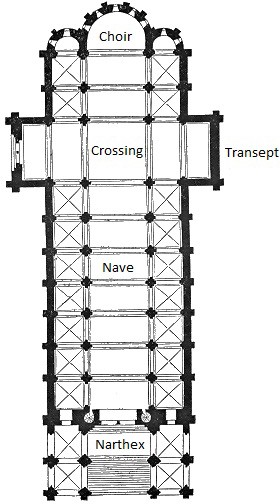

Sometimes we call St. Denis the prototype of gothic cathedrals. It was originally a monastery under the direct patronage of the French kings and was the royal burial place. In fact today you can walk down into the crypt of St. Denis and see the tombs of most of the kings of France. St. Denis was important partly because Charlemagne had been crowned there in 754 CE, and the royal regalia (crown, tunic, sword, spurs, and banner) were there. Between the years 1130 and 1140 the man responsible for St. Denis was Abbot Suger. He was a poor orphan who had been given to the monks at the abbey at about the age of 9 and raised by them. He was educated at the Abbey alongside the future King Louis VII, and when the king left on the second Crusade he left Suger as Regent of the kingdom. Suger was very successful in preserving the stability and solvency of the realm and he was willing to experiment with innovative techniques. When he became abbot, he evaluated the old Romanesque church to see what needed to be done to repair it. As regent he gathered an international assemblage of masons, carvers, metal-workers, mosaicists, jewelers, enamel workers, and he gave lavish commissions. His changes were so innovative that other architects and masons came to see what he had done and took ideas with them to their own building projects. We can best see the changes implemented by Suger by comparing St. Denis to older Romanesque churches. Remember that the characteristics of Romanesque churches include a plan in the shape of a cross with a transept, thick stone walls, and rounded arches.

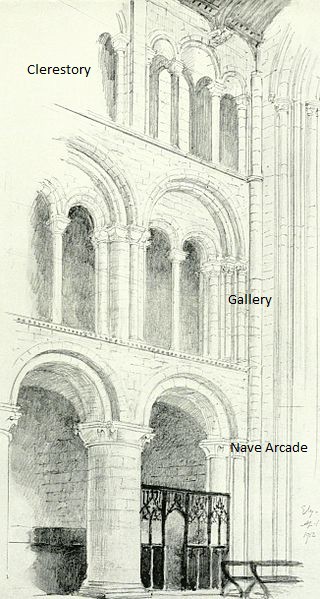

As we discuss churches of this era, it will be easier to refer to the proper names of the building sections. See image 11.11 as an example of a basilica church. It also has aisles on either side of the nave. See image 11.12 as an example of the elevation, or interior walls of a Romanesque church. The bottom row is the nave arcade, the second level is the gallery, and the top layer is the clerestory. See image 11.13 which is an example of the elevation of the abbey church at Mont St Michel. Notice that the walls are thick and because of that, the windows are small. The vaults of the nave are rounded and are supported by heavy pillars.

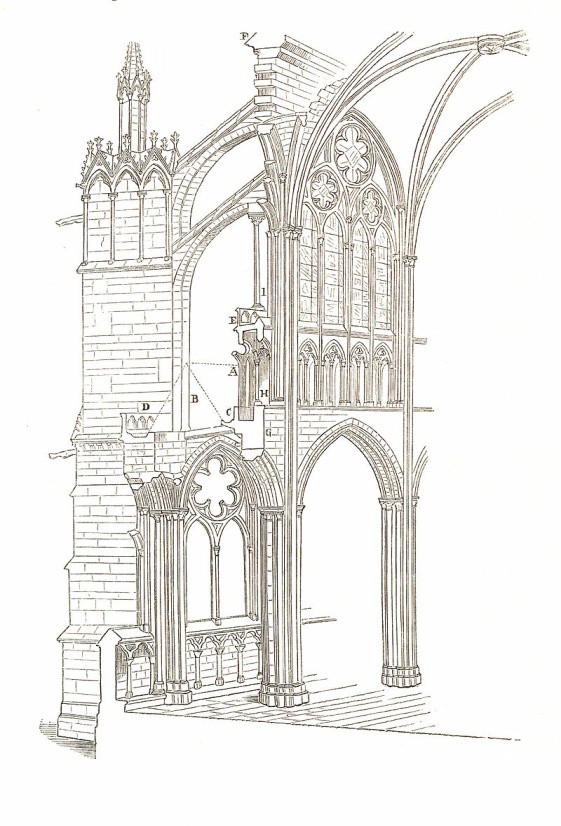

When Abbot Suger rebuilt the church at St. Denis he made major changes. First he added an ambulatory in the choir and seven radiating chapels. He chose to use pointed arches instead of round arches because the pointed arch has two keystones, rather than one. This point support system allowed him to open the interior space of the ambulatory so it was more spacious and it also allows the vaults to take on different shapes. He also used ribbed vaults to lighten the weight of the heavy vaults. See the ribbed vaults in image 11.15. These innovations enabled him to replace some of the thick stone walls with glass windows that also let in more light. The drawing of the elevation of one bay in St. Denis, image 11.16, makes it easier to see how the walls were supported by flying buttresses so that windows could be enlarged.

Suger’s writings explain his theories of aesthetics and light. Through the colored light created by walls of stained glass, the interior of the church could be transformed into a heavenly city, a residence for God. The more light was present, the more God was present. God is light and space. The architectural structure was simply a means to create the spacial and lighting effects which would recreate the celestial light of heaven. Suger wrote that a mundane material would not be appropriate for the house of God. Many of his ideas about light and space come from the Bible. John 8:12 reads “Then spake Jesus again to them, saying, I am the light of the world, he that followeth me shall not walk in darkness, but shall have the light of life.”18 Ephesians 5:14 says “Awake thou that sleepest, and arise from the dead, and Christ shall give thee light.”19 For Abbot Suger, the cathedral could be the abode of God, if it was removed from the darkness of the old Romanesque basilica and transformed with light and space.

The cathedral of St. Denis introduced many new elements to form the “gothic style”. These are the basic elements that make a cathedral gothic:

- Pointed arches to allow more varied configurations in the vaults, choir, transept and nave and aisles

- Ribbed vaults to remove the weight from the ceiling and lessen the pressure pushing down to the ground. This also enabled beautiful designs to be created in the vaults.

- Walls of stained glass to let in the light, create a heavenly space, and tell stories. This not only let in more light, but was a way to control the color of the light.

- Flying buttresses to add support to the outer walls without requiring thick walls of stone

- Ornate, sculptured portals that told biblical stories that created a Bible in stone for the masses.

- Clustered colonnettes were used as interior supports instead of heavy wood or stone pillars.

- A westwork or west façade. This had been added during Carolingian times to provide a place for the ruler to sit during church.

- The westwork was usually divided into three parts to represent the trinity and was topped by two towers

- The westwork also had a rose window to represent the all-seeing eye of God, the circular universe of Plato, and Mary the Rose.

Attributions:

Berger, Eugene; Israel, George; Miller, Charlotte; Parkinson, Brian; Reeves, Andrew; and Williams, Nadejda, “World History: Cultures, States, and Societies to 1500” (2016). History Open Textbooks.

References:

1. Zigeuner, CC By SA 3.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Map_France_1180-de.svg#/media/File: Map_France_ 1180-fr.svg

2. Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:F577.jpg

3. Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Map_of_Venice,_15th_century.jpg

4. Anonymous photo, Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Medieval_ploughing.JPG

5. Politiques et economiques, Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Medieval_peasant_meal.jpg

6. New York Historical Society, CC BY 2.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Magna_Carta_Tour_at_New-York_Historical_Society_(21486712384).jpg

7. David Rumsey Historical Map Collection, Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Vuillemin_and_Migeon,_Paris_in_1180,_1869_-_David_Rumsey.jpg

8. https://sourcebooks/fordham.edu/source/vitry1.asp

9. Etienne Colaud, BNF Francais, from the Chants royaux manuscript. Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Meeting_of_doctors_at_the_university_of_Paris.jpg

10. Photo by Web Gallery of Art, Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Lippo_Memmi_-_Triumph_of_St_Thomas_Aquinas_-_WGA15020.jpg

11. Anonymous photographer, Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File: Dagobert_Ier_ r%C3%A9fugi%C3%A9_%C3%A0_Saint-Denis.jpg

12. Text added By Kristine Betts to image from wikimedia. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File: Plan.cathedrale. Autun.png

13. Jackson, Thomas Graham, Byzantine and Romanesque Architecture, 1913. Online book posted by Flickr The Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Byzantine_and_Romanesque_architecture_(1913)_(14595804018).jpg

14. Photo by Jorge Lascar, CC By 2.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_nave_of_the_abbey_church_-_Mont_St_Michel_(32106381443).jpg

15. Photo by Kathy J. Hartman, CC BY-NC-4.0 License.

16. Photo By Pierre Poschadel, CC BY-SA 3.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Saint-Denis_(93),_basilique_Saint-Denis,_d%C3%A9ambulatoire_3.jpg

17. Photo by French Ministry of Culture, Public domain. By August Ottmar von Essenwein. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Jahrbuch_MZK_Band_03_-_Gew%C3%B6lbesystem_-_Fig_59_Langhaus_der_Abteikirche_St._Denis_bei_Paris.jpg

18. King James Version, New Testament

19. Ibid.