10.5 MEDIEVAL MUSIC

The music of the Medieval Ages was most heavily influenced by the church. When Constantine made it legal to be a Christian with the Edict of Milan in 313, music in the church was still tied to Roman ideas. But when he built St. Peter’s Basilica there was now a new sacred space to which Christians could gather. When Rome fell in about 476, the church was an institution that survived and provided some order and security. We have made references to musical instruments in previous cultures, such as the Lyre in the cemetery at Ur, trumpets found in King Tut’s Tomb, and the Pythagorean Theory of music. Certainly children could whistle mothers sang to their children and shepherds had flutes, but the only music which has survived is that of the church. Different areas of the Christian world developed different music to meet their local liturgical needs. The liturgy is the form of service used to celebrate the mass, and there were several forms of worship including those of St. Jerome, the Ambrosian liturgy for St Ambrose, and an Augustinian liturgy used by St. Augustine.

A major reformer of the early Christian church was Pope Gregory I (590-604) also known as Saint Gregory. The son of wealthy residents of Rome, Gregory did not seek the office of Pope, but spent his early life as a monk in a quiet monastery. During this time the Lombards were attacking, there were terrible floods, and the plague killed about a third of the population of Italy. Against his wishes, Gregory was appointed pope and because of his efforts, we call the music that comes out of this time “Gregorian Chant”, although much of this type of music could also have been written by later popes. Another term for this type of music is Plainchant.

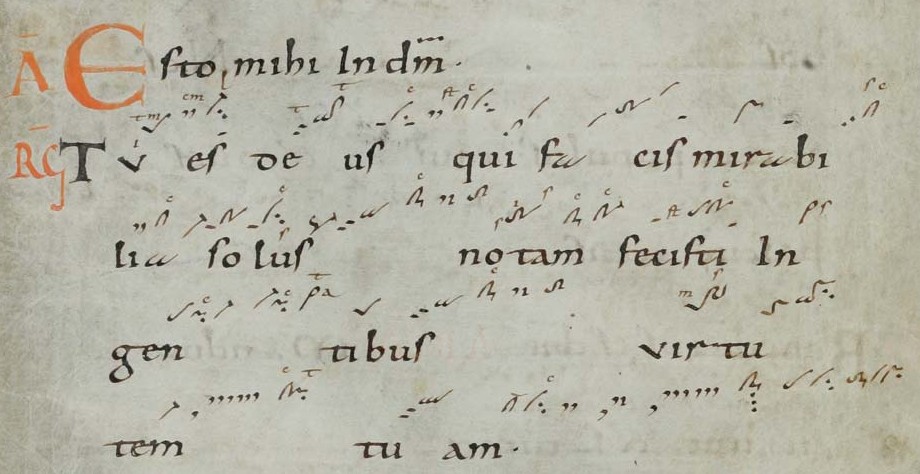

Early music was syllabic, meaning that each note was assigned to a single syllabic of the text. Later, neumes were used to indicate the number of notes that should be sung to each syllable of text. There would be musical gestures to indicate whether the music went up, or down, or up and then down. This helped, but you had to hear the music to learn it. This music was meant to be sung by people who already knew it. So it could be used to study and memorize the music, but not for performance. There were theoretical writings about music, but no one had yet determined how to write it down. See image 10.75 for an example of what early music looked like before the invention of musical notation.

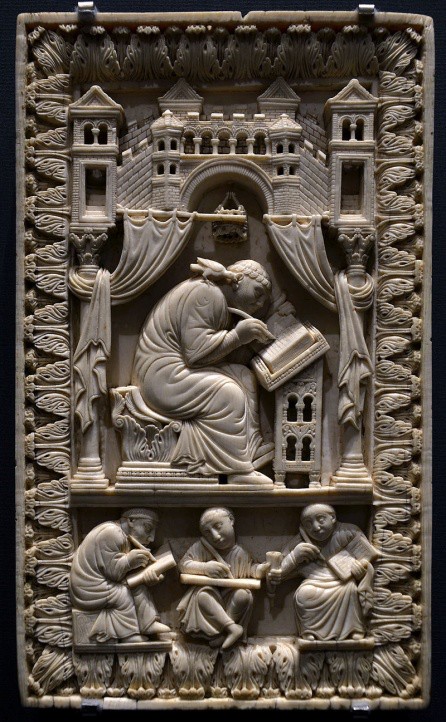

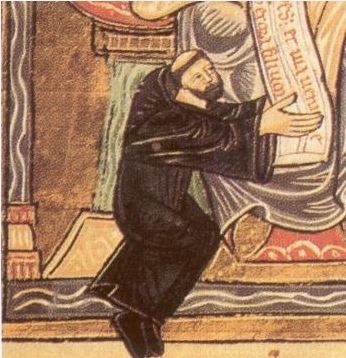

As part of Charlemagne’s interest in the liturgy, changes were again made to the music of the church. He set about to simplify, codify, and unify the liturgy for all western Christians. This was quite a task, since the liturgy was based on the psalms of David and could be different depending on many factors. There could be specific music for holidays that were fixed on the calendar, such as Christmas, and other music for holidays that moved on the calendar, such as Easter, or specific music for a saint’s day. This is described by the term proper. The term ordinary in western liturgies refers to music and text that does not change and is constant. The monasteries at St. Gall and Cluny continued to play a part in the music of the time. Images 10.76 and 10.77 are two of many artists’ renderings of the inspiration Pope Gregory received to make changes to the chant. Later in his life Pope Gregory was beatified and designated a saint.

One important contributor to the changes in music was Odo of Cluny, 927-942. He was the son of Abbo and his father wanted him to become a knight, so he sent him to live with a military man and his family, William, the Duke of Aquitaine. Eventually he convinced his father that he should serve in the church so early in his life he went to Paris where he studied music and poetry. Eventually Odo went to the Abby of Cluny where he is credited with writing dozens of choral pieces based on the Old Testament Psalms. As he traveled to other monasteries he set up choirs, which required that he find a way to teach music to the new choir members. This was Odo’s great gift to music: he arranged the notes into an orderly progression from A to G, proposed a method to measure intervals, which is the difference in pitch between the notes, and used an instrument called the monochord to demonstrate how the notes sounded and how they related to each other. His writings on these ideas opened the door for later innovators to take the next step.

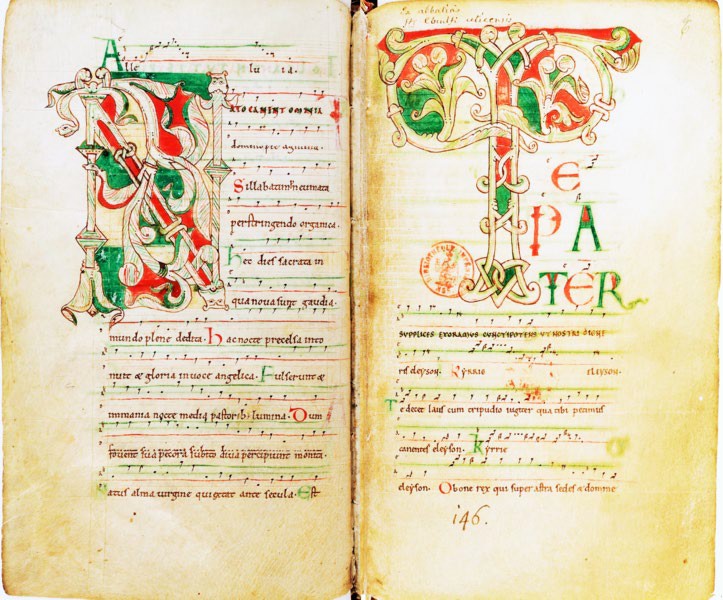

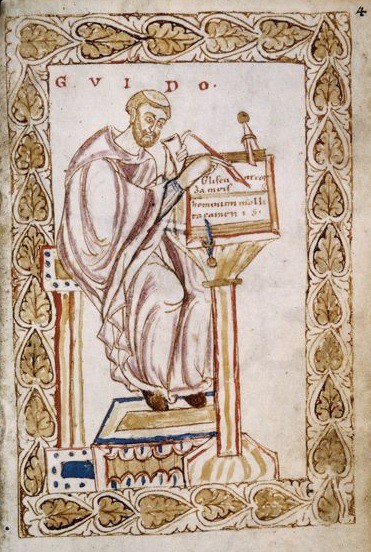

Even though Odo’s innovations made music available to monasteries all over Europe, it was Guido of Arezzo that made the biggest leap in musical notation. He was born some time at the end of the first millennium and became a Benedictine monk. Guido is credited with devising musical syllables and assigning those syllables to specific lines on a musical staff. He named the notes with letters of the alphabet and placed the same note on the same line, making it easier to transmit and learn music. It was no longer necessary for a singer to hear someone sing music, instead they could learn by the notation. See image 10.79 for an example of Guido’s idea.

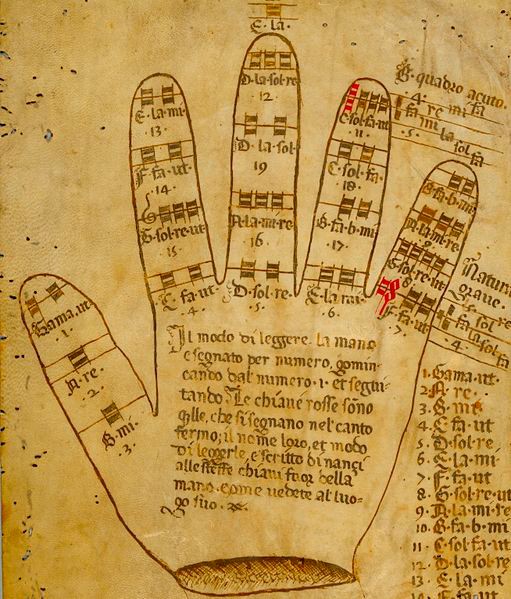

Guido is also known for developing the Guidonian Hand which could be written on the student’s hand and referred to when learning a musical number. Watch this video to see how it works.8 Or watch this one to see it in action.9 The idea of the Guidonian hand is that each portion of the hand represents a specific note within the hexachord system, which spans nearly three octaves. In teaching, an instructor would indicate a series of notes by pointing to them on their hand, and the students would sing them. There have been several variations in the position of the notes on the hand, and no one variation

is definitive but, as in example 10.80 the notes were mentally superimposed onto the joints and tips of the fingers of the left hand. GUIDO’S MUSICAL INNOVATIONS

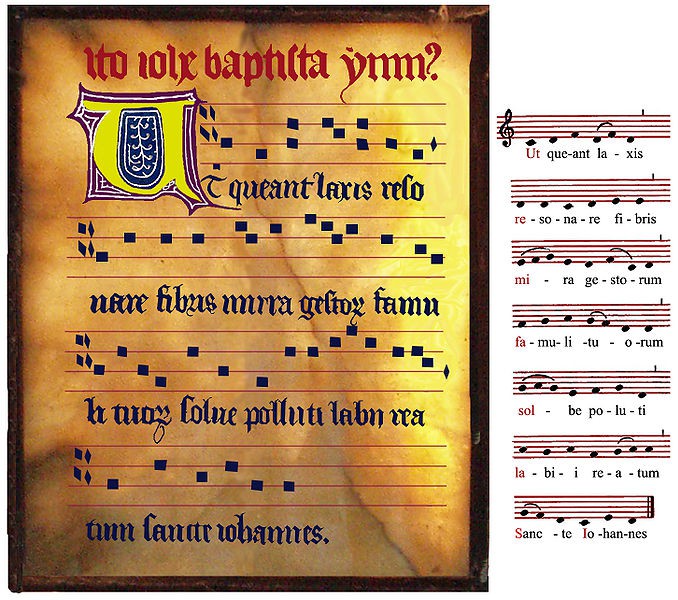

This device allowed people to visualize where the half steps were, and to visualize the interlocking positions of the hexachords (the names of which—ut-re-mi- fa-sol-la—were taken from the hymn Ut queant laxis). Ut was later changed to “do”, which is what modern musical notation still uses. In image 10.82 see that the names of the notes are shown in red, and you can see that each note is one step higher on the scale. Watch this short video to see how the hymn to St. John was the basis of Guido’s system.11

So plainsong, also known as Gregorian chant has very specific characteristics. This type of medieval music is simple by modern standards. There is a short lecture included for this lesson. To study the music, first read this section, and then listen to the lecture. You will hear the basic musical elements and learn why the music sounds the way it does.

The basic elements of Plainsong are:

- Monophonic. This means that all of the voices sing the same melody simultaneously in block harmony. This helps to express the unity of the church.

- Vocal only. No musical instruments were normally used.

- Unmeasured. In western music, the strong beat is on the first note in a measure. Since there were no measures, there were no strong and weak beats.

These three basic elements caused the music to have a calm other-worldly feeling. Gregorian chant is pure melody, and because of its lack of meter, it seems to wander indefinitely. This is one of the values of this religious music. Because it is religious and it deals with the eternal, it removes the temporal element of measured time from the mundane world. It also makes the music soothing, hypnotic, and ethereal. Gregorian chant was intended to draw your mind and heart closer to God. The great Romanesque churches were built with high stone vaults to reflect the monophonic music sung by the choirs.

We spoke of the Abbess Hildegard (1098-1179) of the nunnery of Bingen when we talked about illuminated manuscripts. See image 10.74. It is also appropriate to mention the Abbess here because of the great contributions she made to the music of her time. She wrote plainchants to go with the poetry she also composed. One example of this is “Columba Aspexit” written to celebrate Saint Maximinus:

Her poem reads:

The dove peered in Through the lattices of the window

Where, before its face, A balm exuded

From incandescent Maximinus.

The heat of the sun burned

Dazzling into the gloom;

Whence a jewel sprang forth

In the building of the temple

Of the purest loving heart.12

Click the link below to listen to a modern rendition. Note the continual chord played behind the singing of the chant.13

The cathedral schools in Paris were also very active in producing and changing the music of the times. When the cathedral school was built at the new cathedral of Notre Dame of Paris, it became the center of intellectual growth. Much of what we know of this school and its students and masters comes from the notes of a student at the university in 1280. The monophonic music of plainchant was evolving to something much more complicated. Writers and performers of music had been experimenting with polyphony, singing two or more melodies at the same time, for years. At first, the original melody was sung with an additional melodic line added and sung at the same time with the same free flowing rhythm of the plainchant. We call this organum. As innovation increased there were soon changes in the added line, perhaps it went up when the main melody went down, or maybe more notes were added. Then perhaps another counterpoint melody might be added, or the writer may have added different rhythms. In 1160 Master Leonin is thought to have added a faster line above the tenor melody which was called the descant. While the tenor holds the note, the descant increases in speed. In 1180, Master Perotin added new words above the slow, almost plodding tenor melody. He also caused the tenor line to move faster in certain sections, and called it the descant clausula. Now both the tenor and the line above are moving faster.

Keep in mind that often ideas and values appeared in more than one medium. So for instance, you might look at the Roman gate at Autun to see an example of Organum duplum that might have been written by Leonin. See image 10.84. Notice the upper layer of stones has more windows with rounded arches than the lower register. This could be compared to the upper notes in the music moving more swiftly over the longer-held tenor notes in the bottom register. Also, as time passed architecture became more complicated, just as the music added more parts, more notes, and more instruments.

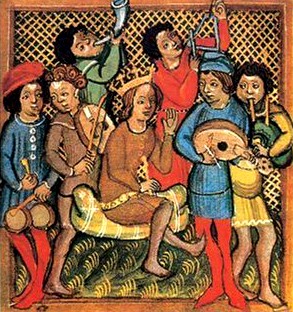

We have spoken of the music played in the monasteries, churches, and cathedrals, but there was also secular music played at the time. Secular music was likely improvised because performers probably had neither the knowledge required to commit their songs to paper, nor any desire to share what they wrote with potential rivals. The courts were especially interested in having some control over music and they supported noble composers who wrote poetry to be performed in their castles, manors, and halls. These courtly performers were called troubadours in southern France, trouveres in northern France, minnesingers in Germany and Austria and cantigas in 13th century Spain. Their topics were courtly, although platonic, love. They sang of crusaders, knights, and praise for ladies. See images 10.85 and 10.86.

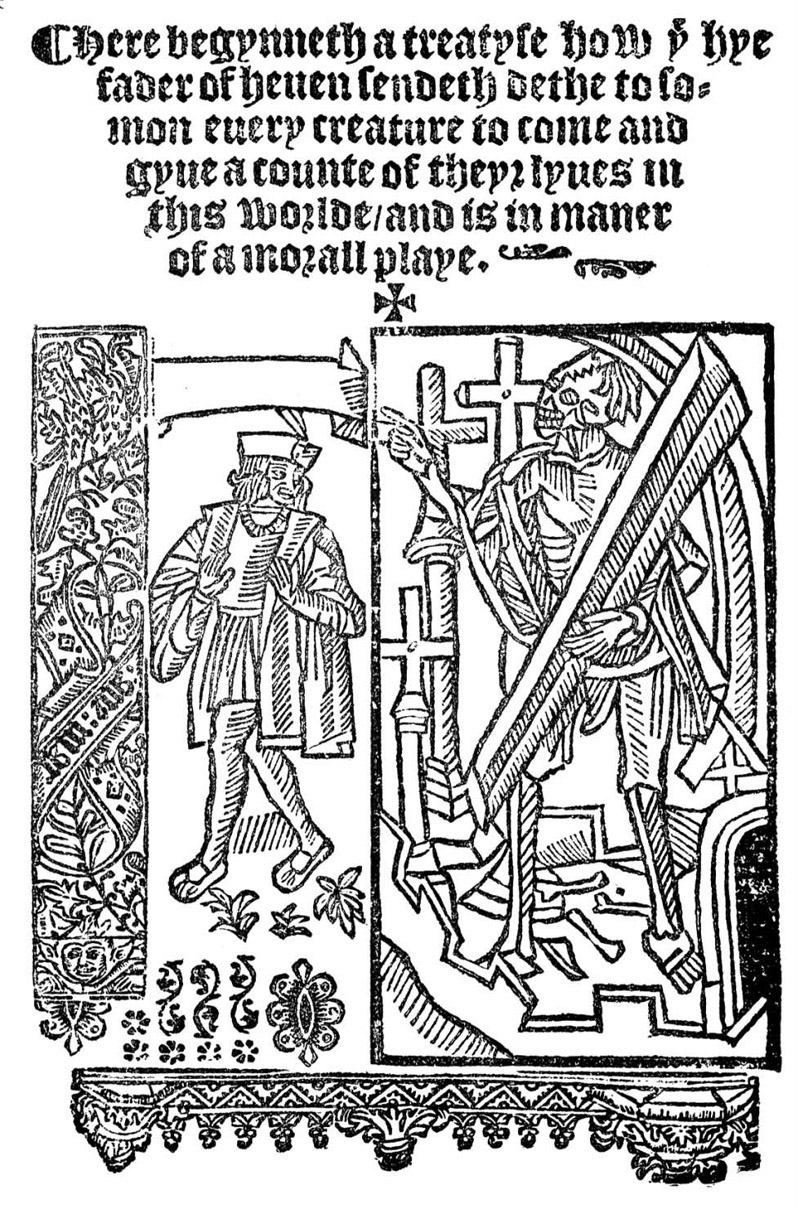

These were songs to enliven parties, performed in public squares on feast days, and may have been paid for by craft or merchant guilds. We might also think of these as the next logical step to morality plays such as Everyman, a 15th century story of a man who encounters allegorical characters that force him to look at how he has lived his life. Death informs him that he will soon die and when he is deserted by unfaithful friends, beauty, knowledge, and wealth, he learns that he can only count on the Good Deeds he accomplished in life. This very short, 900 line play can be read on the Internet.18

Attribution:

Berger, Eugene; Israel, George; Miller, Charlotte; Parkinson, Brian; Reeves, Andrew; and Williams, Nadejda, “World History: Cultures, States, and Societies to 1500” (2016). History Open Textbooks.

References:

1. Photo by Unbekannter Schreiber, Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tu_es_deus.jpg

2. From Antiphonary of Hartker, 997 CE, Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Gregory_I_-_Antiphonary_of_Hartker_of_Sankt_Gallen.jpg

3. Photo by Vassil, CC0. 10th century ivory from the cover of a sacramentary, In the Kunsthistories Museum in Vienna. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kunsthistorisches_Museum_10th_century_ivory_Gregory_the_Great_2306 2013.jpg

4. Anonymous photographer, Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Odo_Cluny-11.jpg

5. Photo by Jchancerel, Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:AbbayeSaintEvroultLettrines_(2).png

6. Anonymous Photographer, Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Guidonian_hand.jpg

7. From Dutch Wikipedia, Robbot, Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Guido_van_Arezzo.jpg

8. https://video.search.yahoo.com/yhs/search?fr=yhs-symantec-ext_onb&hsimp=yhs- ext_onb&hspart=symantec&p=guidonian+hand#id=1&vid=f873eee31362e0098af1204c9b17a9df&action=view

9. https://video.search.yahoo.com/yhs/search?fr=yhs-symantec-ext_onb&hsimp=yhs- ext_onb&hspart=symantec&p=guidonian+hand#id=6&vid=fe5d4418ab799675a05db4c898e18af7&action=view

10. Photo by GRosa, Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Escala_musical.jpg

11. https://video.search.yahoo.com/yhs/search?fr=yhs-symantec-ext_onb&hsimp=yhs- ext_onb&hspart=symantec&p=ut+queant+laxis#id=3&vid=8581ddf14d33b423cab1b094ab0e1e1e&action=click

12. Listen. Joseph Kerman, University of California, Berkeley, Worth Publishers, 1992, p 68.

13. https://video.search.yahoo.com/yhs/search?fr=yhs-symantec-ext_onb&hsimp=yhs- ext_onb&hspart=symantec&p=columba+aspexit#id=2&vid=edb0c6fea066a9f2d496a0ebe71fc793&action=view

14. By Evelyn Simak, CC BY-SA 2.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_convent_chapel_at_Old_Hall_-_stained_glass_window_-_geograph.org.uk_-_665582.jpg

15. Photo by Guido Radig, CC BY-SA 3.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Autun_-_Porte_Romaine.JPG

16. Photo by Wikielwikingo Anonymous. Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Troubadours_berlin.jpg

17. Photo anonymous, Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Codex_Manesse-Minnes%C3%A4nger_1.jpg

18. https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/basis/everyman.asp

19. Photo anonymous, Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Everyman_first_page.jpg