10.3 Feudalism

Charlemagne was able to rule due to his own personal magnetism, but he was also able to accomplish much because he held those under him to a strict code of service. Chivalry and the feudal system enabled him to extract a pledge of fealty and control those under him. The feudal code was based on a pyramid structure of power. At the top was the feudal lord, in this case Charlemagne, who protected his manor and his possessions. Each vassal owed certain services in battle, financial gifts on specified occasions, and hospitality when the lord passed through his territory. The relationship between the lord and holder of the fief (land) was a moral obligation assumed by ceremony. The lord received his vassal, who knelt before him, offered his hands, and pledged his oath. See an example of a vassal pledging an oath in image 10.31.

Out of the chaos and mayhem of the tenth and eleventh centuries, East Francia—the eastern third of Charlemagne’s Empire that is in roughly the same place as modern Germany—and England had emerged as united and powerful states. Most of the rest of Christian Western Europe’s kingdoms, however, were fragmented. This decentralization was most acute in West Francia, the western third of what had been Charlemagne’s empire. This kingdom would eventually come to be known as France. Out of a weak and fragmented kingdom emerged the decentralized form of government that historians often call feudalism. We call it feudalism because power rested with armed men in control of plots of agricultural land known as fiefs and Latin for fief is feudum. They would use the surplus from these fiefs to equip themselves with weapons and equipment, and they often controlled their fiefs with little oversight from the higher-ranked nobles or the king.

How had such a system emerged? Even in Carolingian times, armies in much of Western Europe had come from war bands made up of a king’s loyal retainers, who themselves would possess bands of followers. Ultimate control of a kingdom’s army rested with the king, and the great nobles also exercised strong authority over their own fighting men. The near constant warfare of the tenth and eleventh centuries, however, meant that the kings of West Francia gradually lost control over the more powerful nobles and the powerful nobles often lost control of the warlords of more local regions.

As a result of constant warfare, power came from control of the land. Whoever controlled the land and could extract surplus from the occupants could then use this surplus to outfit armed men. The warlords who controlled fiefs often did so by means of armed fortresses called castles. At first, especially in northern parts of West Francia, these fortresses were of wood, and might sometimes be as small as a wooden palisade surrounding a fortified wooden tower. Over the eleventh and twelfth centuries, these wooden castles were replaced with fortifications of stone.

Suscinio Castle, in France, is an example of a stone castle. When it was built in 1218 for Peter I, Duke of Brittany, it was first used as an unfortified manor used to manage an estate. In 1229, his son John I fortified it so that it could be used as a castle. A castle had two roles: it would protect a land from attackers and serve as a base for the control and extortion of a land’s people. Castles often had a mote filled with water to prevent enemies from entering, a drawbridge that could be raised and lowered, small holes that allowed those inside to fire on attackers and the Keep, which was the highest point of the castle and the center of the defense.

Knights and castles came to dominate West Francia and then other parts of Europe for several reasons. The technology of ironworking was improving so that iron was cheaper (although still very expensive) and more readily available, allowing for knights to wear more armor than their predecessors. Moreover, warfare of the tenth and eleventh centuries was made up of raids (both those of Vikings and of other Europeans). A raid depends on mobility, with the raiders able to kill people and seize plunder before defending soldiers arrived. Mounted on horseback, knights were mobile enough that they could respond rapidly to raids. The castle allowed a small number of soldiers to defend territory and was also a deterrent to raiders, since it meant that quick plunder might not be possible.

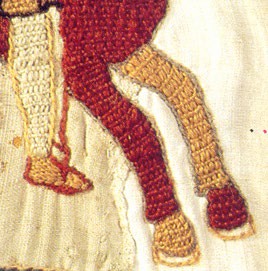

A knight’s equipment—mail, lance, and horse—was incredibly expensive, as was the material and labor to construct a castle. Although knights had originally been whichever soldiers had been able to get the equipment to fight, the expense of this equipment, and thus the need to control a fief to pay for it, meant that knights gradually became a warrior aristocracy, with greater rights than the peasants whose labor they controlled. Indeed, often the rise of knights and castles meant that many peasants lost their freedom. They became serfs, peasants who, although not considered property that could be bought and sold like slaves, they were nevertheless bound to their land and subordinate to those who controlled it. Knights in the eleventh century wore an armor called chain mail, that is, interlocking rings of metal that would form a coat of armor. (See Image 10.35) The knight usually fought on horseback, wielding a long spear known as a lance in addition to the sword at his side. With his feet resting in stirrups, a knight could hold himself firmly in the saddle, directing the weight and power of a charging horse into the tip of his lance.

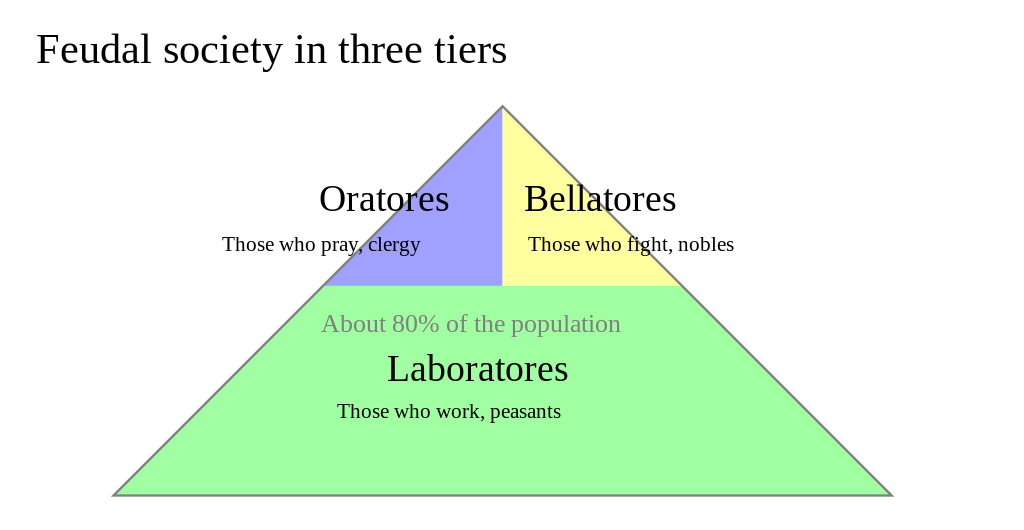

In theory, the feudal system consisted of those who pray (clergy), those who fight (knights and lords), and those who work the land, see image 10.32. However, there were problems with the feudal system because once the knight made the oath to the lord and had the land and its fruits; there was not much incentive for him to keep his word. He might show up late to a battle, bring fewer knights or less equipment than promised, or not show up at all. The lord had to decide whether it was important enough to go after his vassal and remove him from the land, or just let it go. It was not easy to stage a battle if some of your men and materials did not show up. Although the oaths did not always remain intact, the feudal system was a powerful way to maintain order, gather armies, and wage war.

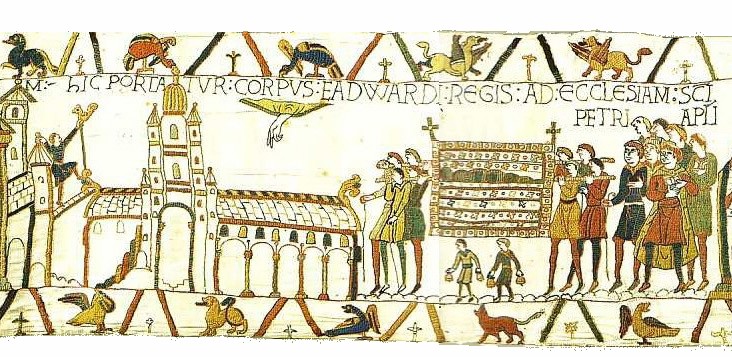

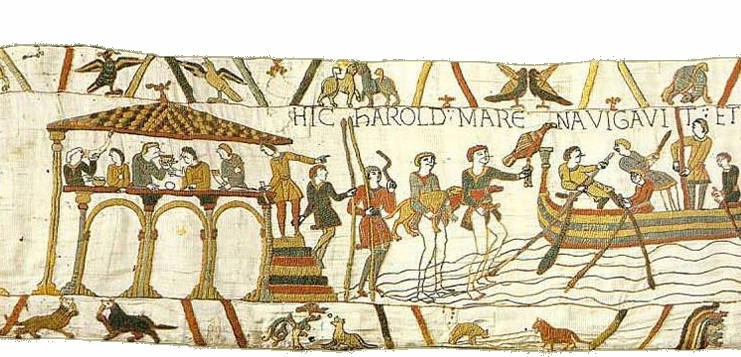

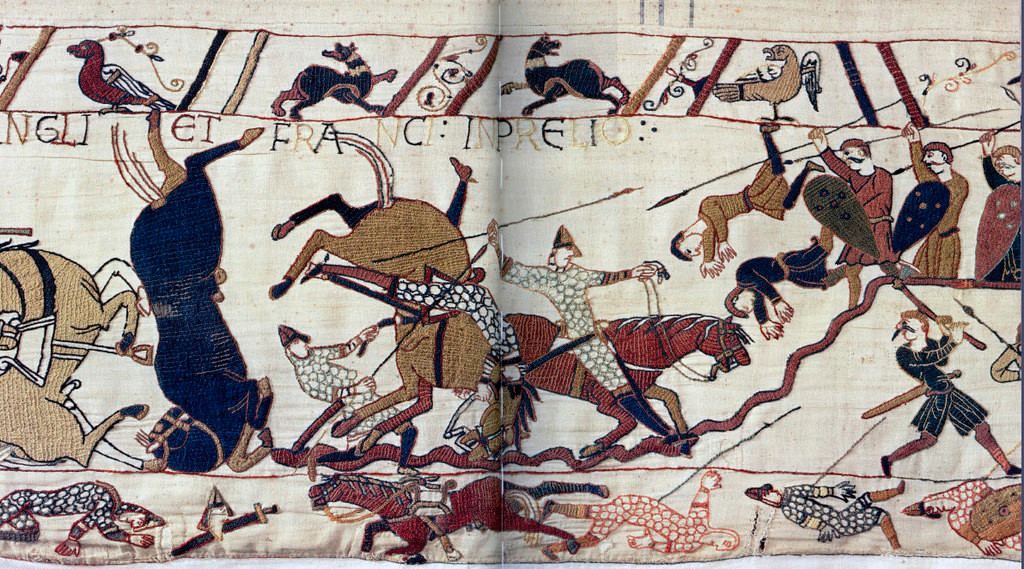

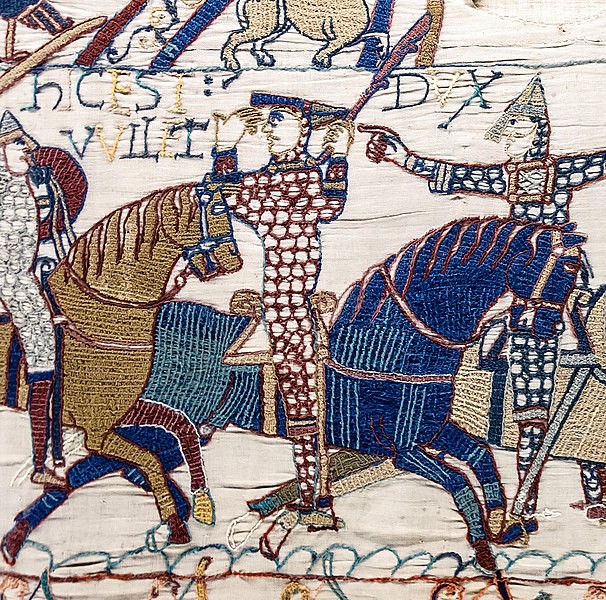

One of the great battles of the middle ages was the Battle of Hastings fought in 1066, which was the invasion of England by the French king, William the Conqueror. The most important work of art from this era is the Bayeux Tapestry, created to tell the story of the battle from the winner’s perspective. It was made to cover a plain strip of masonry over the nave arcade in the Cathedral in Bayeux and was embroidered 20 years after the end of the battle by the women of the household of Bishop Odo. Even though it was housed in a church, it is not religious art, but secular art that tells the story of a battle. The tapestry has 79 scenes and reads from left to right like a comic strip. Sections 1-34 tell the story of William’s interactions with Harold, another pretender to the throne. Sections 35-53 show the preparations for battle, and sections 54-79 show the battle. It is not really a woven tapestry but a work of embroidery on coarse linen and is 20 inches high and 231 feet long. There is one copy in England and another in Normandy. A Victorian copy was made that reflected the beliefs of the era, covering the nudity that was present in the original version stitched in the 1080’s.

The basic story of this war revolves around who wanted to be the next king of England. Both Harold and William had hereditary claim to the throne. When Edward the Confessor, the current king, died, Harold was sent as a messenger to tell William that he (William) would be the new king and would succeed Edward. See image 10.36 where Harold is shown in the tapestry placing his hands on the reliquaries that sit on two alters. Here he swears to uphold William’s claim to the throne.

Notice the hand of God in the clouds above blessing the church where Edward’s body is carried for burial. Harold, false to his word and his oath on the reliquaries, has himself crowned king, so William decides to invade England and take back what he considers to be his rightful crown.

The registers below the battle scenes are strewn with dismembered bodies being plundered by scavengers, fallen horses and weapons, and men strewn on the battlefield.

Artistically the creators of this work divided the 20 inch fabric into three sections horizontally, placing symbols of the main characters in a narrow section at the top, Latin script describing some of the events, the main action in the center section, and symbols, animal characters, and commentary on the actions in the lower registers. Animal figures from bestiaries, sculptures, and Aesop’s fables represent stories that we may not identify easily, but everyone looking at the panels then knew and understood. To begin a new section of the story, the artist might place a tree or a building as a divider. To show an episode apart from the main story, like a dream, the artist might reverse the order of the action so that it moved from right to left, rather than left to right. The scenes are two dimensional and there is little suggestion of space. Color is not natural, but is used for interest, so hair might be blue, horses red or green, and faces are outlined, although there does seem to be some effort at portraiture.

The battle for the crown and throne of England lasted 9 hours, and in the end, Harold took an arrow through his eye and lost. William lost three horses in battle – so he lifted his helmet so his men could see that he was alive and continuing to fight. The last scene is missing from the tapestry, but we know how the story ends. William won the battle and was crowned the king of England. So what can we learn from the Bayeux Tapestry? We can learn about the brutality of the battles they fought, what types of weapons they used, the importance of relics and oaths, and how astronomical events impacted thought. It is an encyclopedia of medieval dress and thought.

THE CRUSADES

In addition to the Battle of Hastings, another series of wars and battles had important impact on medieval Europe. We call these the crusades. On 19 August 1071, the forces of the Byzantine Empire met those of the Great Saljuq Empire at the Battle of Manzikert near the shores of Lake Van in Armenia. The Byzantine field army was annihilated. In March of 1095, Alexios Komnenos (r. 1081 – 1118) who had seized control of the Byzantine Empire sent a request to the pope for military assistance. In 1095 the Seljuk Turks also closed Jerusalem to all Jewish and Christian pilgrims. The long-term consequences of this closure and Komnenos’s request would be earth-shaking.

From about 1096 knights of most of Western Europe began to fight against Muslims in the Middle East. These battles are generally known as the Crusades. A crusade was a war declared by the papacy against those perceived to be enemies of the Christian faith, and they were usually, but not always, Muslims. Some of the Crusades were also against heretics such as the Arians, the Cathars, and the Albigensians. Though the Crusades lasted into the 16th century, none after 1291 set foot in Palestinian territory. We will look at several reasons the crusades occurred. Urban II (r. 1088 – 1099) was the pope who received Komnenos’s request for help. Urban, an associate of reformers like Gregory VII and other church leaders who were seeking to change society, had been looking to quell the violence that was often frequent in Western Europe. This violence was usually the work of knights. Reformers like Urban and Gregory sought for ways that knights could turn their aggression to pursuits that were useful to Christian society rather than preying upon civilians. Fighting against Muslims in Sicily and Spain would be a way to channel knightly aggression towards Christendom’s external enemies rather than preying on local peasants and other landed families. So one of the reasons the crusades happened was to channel the violent energy of the knights into more productive paths.

A second reason that led to Pope Urban II’s turning much of the military might of Western Europe to the Middle East was the sacred nature of Jerusalem. The city of Jerusalem was where Jesus Christ was said to have been crucified, to have died, and to have risen from the dead. As such, the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, built on what was said to be the empty tomb from which Christ had risen, was the holiest Church in the Christian world—and this Church had been under the control of Muslims since Caliph Umar’s conquest of Palestine in the seventh century. The city remained important to Christians, however, and, even while it was under Muslim rule, they had traveled to it as pilgrims, that is, travelers undertaking a journey for religious purposes. When the Seljuk Turks closed Jerusalem to pilgrims, western Christendom sought ways to reclaim it.

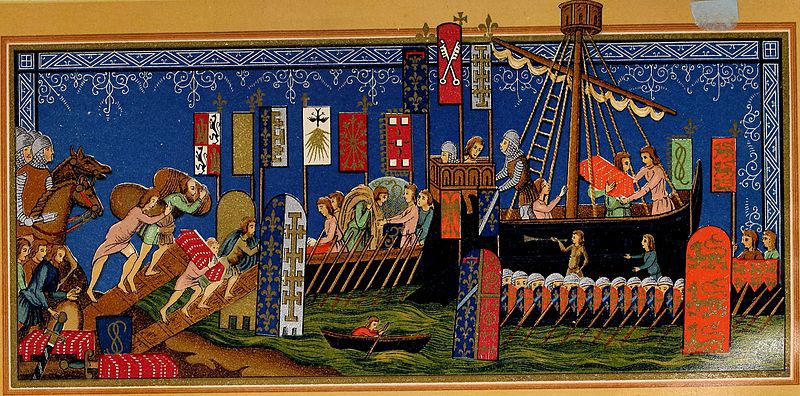

There were other reasons the crusades occurred. One was because Christians of the time were seeking forgiveness tor their sins. People of this time believed that their sinful acts condemned them to hell, but righteous acts could balance this and remove the punishment. One of the ways to remove the damnation was to make a pilgrimage to an important religious site. The crusaders took seriously their sins and they wanted to have those sins forgiven. They believed that Jerusalem was a holy place and the pope promised them that if they went on a crusade, the punishment they deserved for their sins would be removed so that they could go to heaven. Pope Urban thus conceived of the idea of turning the military force of Western Europe to both shore up the strength of the flagging Byzantine Empire (a Christian state), and return Jerusalem and the Church of the Holy Sepulcher to Christian rule after four centuries of Muslim domination. Participating in a crusade would grant a Christian forgiveness of sins, but there were other reasons people went on crusade: serfs may have been freed from their role in the feudal system enabling them to own land and have some autonomy; taxes may have been forgiven and debt cancelled, and it was an opportunity to take spoils and obtain riches in the new lands.

Pope Urban “preached” the first crusade at the council of Clermont in Auvergne, in November, 1095. There are 5 different versions of his speech on the Internet, click this link if you are interested in further reading.16 Urban encouraged the faithful to take up the cross. The word crusade comes from the Latin word crux, meaning cross. To take up the cross meant to become a crusader, so they sewed crosses on their tunics and painted crosses on their shields. As these forces mustered and marched south and east, the religious enthusiasm accompanying them often spilled out into aggression against non-Christians other than Muslims. One group of Crusaders in the area around the Rhine engaged in a series of massacres of Jewish civilians, traveling from city to city killing Jews and looting their possessions before this armed gang was forced to disperse.

The effects of the crusades were diverse. Economically there were new trade routes established and new products were exchanged. Since travel was a little quicker by sea, port cities such as Venice, Pisa, and Genoa gained in importance and size. Feudalism was weakened because knights left to take up the cross, some sold their fiefs to have money to travel and equipment to fight and serfs were given freedom to go, leaving fewer of the working class to do the work. There was also an increased use of portable money needed to pay for travel. This also resulted in banking institutions where crusaders could deposit their money in one place, and withdraw it in another. There were more ships built, more goods manufactured, and improved trade routes. As a result of the crusades, popes gained more power and the Christian church became wealthier.

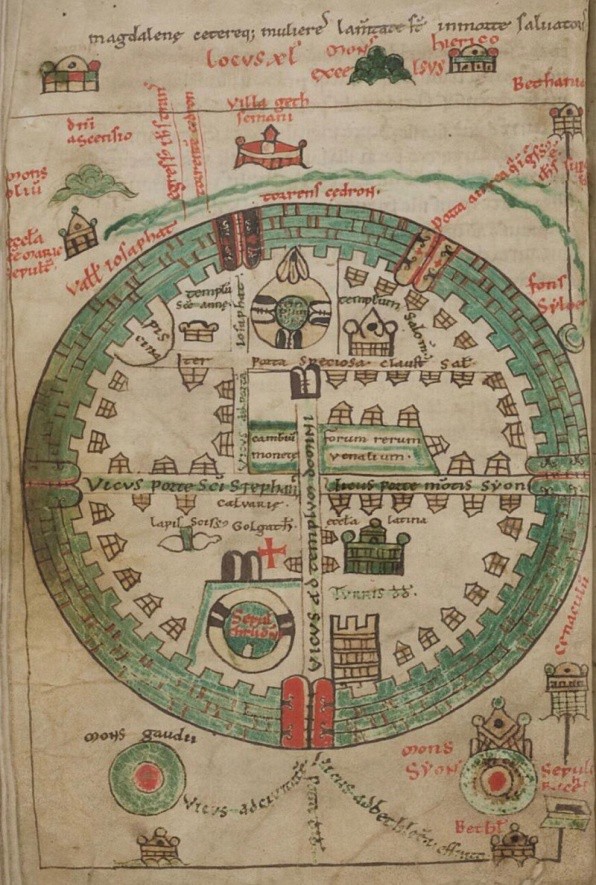

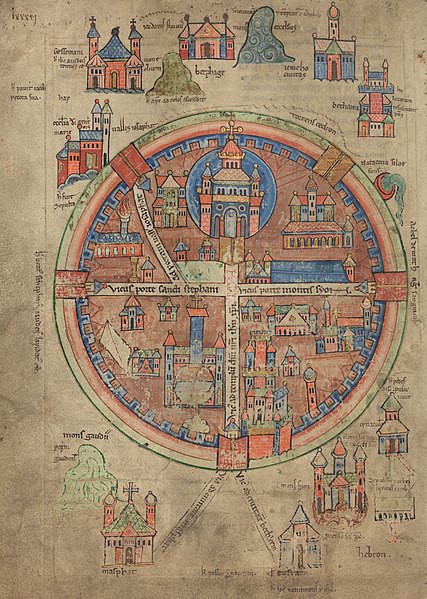

The Crusades also increased efforts to draw maps of the Hold Land, which would help travelers pass sites in the future.See images 10.46 and 10.47 for two versions of maps of the Holy Land. There were four Crusader states: the County of Edessa, the Principality of Antioch, the Kingdom of Jerusalem, and the County of Tripoli which can be seen in the maps. Sometimes these communities made their own treaties with their Muslim neighbors which angered their fellow Christians.

The Templars, a group of knights who could also be called monks, became very powerful during the crusades. Many of them were landed knights who had amassed much wealth. Since they also took vows like the monks did, they were more reliable than other vassals. Templars were more obedient to their leaders and could be counted upon in difficult battle situations. On the other hand, they were not obligated to obey the King of Jerusalem, for instance, and might not honor treaties made by him. Local bishops might resent the Templars because their allegiance was not to them. Templars also had strict rules, which were written down and shared with other Templars. So they were taught where to camp, not to be tricked by a Muslim “feint” that might not be a real attack, and to go to their position, hide, and wait for orders. They were even counseled to bring a spoon, as it might come in handy. So the Templars were military units that were often very wealthy and owed their allegiance to whoever bought their services.

Another influence from the crusades on the Holy Land was the infusion of architectural ideas from Europe. As castles had been built in the west, they were built as places of security in eastern lands too, and with those castles came Romanesque ideas. One example is the Crac des Chevaliers, built in Syria, near the northern border of present day Lebanon. Crac des Chevaliers was built by the Hospitallers, a class of knights that was originally sent to watch after the health of the crusaders, but became a military group much like the Knights Templar. It was begun in about 1142 and was then captured in the middle of the 13th century by the Muslims. It has two thick stone walls and a mote and it was fed by an aqueduct.

The cistern within the walls allowed those inside to have access to water even if they were besieged and could accommodate up to 2,000 men. The castle sits atop a high mountain to guard the road from Antioch to Beirut and provides access to the Mediterranean and Lake Homs. Unfortunately, it is now caught in the crossfire of a 21st century Syrian war and has suffered bullet holes, damage to walls and columns, fires, and misuse by the military garrisons living in it.

There were several campaigns that might be considered crusades, some more successful than others. Some historians list eight crusades between 1096 and 1291. Some crusades were preached by popes and funded by kings, emperors and princes. Others were less organized might not really fit into the category of a crusade at all. Were the fall of Jerusalem and the Fall of Constantinople “crusades”? What about the Children’s Crusade of 1212, which never really left for Jerusalem and may not have had any children in it. What about the taking of Acre in 1291 by the Mamluks, was this also a crusade?

You may also enjoy the following links to video information about Feudalism and the Bayeux Tapestry.

Bayeux Tapestry, Bayeux Tapestry 2, Causes and Effects of the Crusades

Attribution:

Berger, Eugene; Israel, George; Miller, Charlotte; Parkinson, Brian; Reeves, Andrew; and Williams, Nadejda, “World History: Cultures, States, and Societies to 1500” (2016). History Open Textbooks.

References:

1. Anonymous, Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:ArnauMirPal_RamEr.jpg

2. Nikkimaaria,Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Feudal_organization.svg

3. Fab5669, CC BY-SA 3.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sarzeau_-_Suscinio_(5).JPG

4. Lieven Smits, CC BY-SA 3.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Suscinio_castle_South_aerial_view.jpg

5. Photo by Wikigraphists, Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bayeux_haubert.JPG

6. Photo by Myrabella, Public domain.https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bayeux_Tapestry_scene23_ Harold_oath_William.jpg

7. On the website of Ulrich Harsh, Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:BayeuxTapestryScene26.jpg

8. Photo by hs-augsburg.de. Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:BayeuxTapestryScene04.jpg

9. Photo by Myrabella, Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bayeux_Tapestry_32- 33_comet _ Halley_Harold.jpg

10. Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bayeux_Tapestry_Horses_in_Battle_of_Hastings.jpg

11. Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Fleeing_ bayeux_tapestry_ (cropped_to_show_ details_of_ Bayeux_Stitch).png

12. Photo by Myrabella, Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bayeux_Tapestry_scene55 _William_on_ his_horse.jpg

13. Photo by Myrabella, Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bayeux_ Tapestry_scene57_ Harold_ death.jpg

14. From Heine, Heinrich, 1797-1856, Pictures of Travel. Photo by Library of Congress. Flickr no restrictions. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Embarking_for_the_crusades_(Miniature_in_a_manuscript_of_the_XIVth_Century).jpg

15. Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pope_Urban_II_urging_kings_and_knights_to_join_a_Crusade,_Nov._1095_LCCN2005692122.j pg

16. https://www1.cbn.com/spirituallife/calling-for-the-first-crusade

17. Hugues de Saint-Victor (1096?-1141), Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:St_omar_map.jpg

18. From Historia Hierosolymitana, Robert the Monk, 13th century. Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org /wiki /File:Upsala_map.jpg

19. Photo by Xvlun, CC By-SA 2.5. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Crac_des_chevaliers_syria.jpeg

20. Photo by Effi Schwrizeer, Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Crac_des_Chevaliers2.JPG