10.2 Charlemagne – The Carolingian Renaissance

Charlemagne, whose name means Charles the Great, spent nearly the entirety of his reign, (r.768-814) leading his army in battle. To the southeast, he destroyed the khanate of the Avars, the nomadic people who had lived by raiding the Byzantine Empire. To the northeast of his realm, he subjugated the Saxons of Central Europe and had them converted to Christianity—a sometimes brutal process. When the Saxons rebelled in 782, he had 4,000 men executed in one day for having returned to their old religion. By the end of the eighth century, Charlemagne ruled nearly all of Western Europe. Indeed, he ruled more of Western Europe than anyone since the Roman emperors of four centuries before.

It was Christmas day in Rome, in the year 800 CE. The cavernous interior of St. Peter’s Church smelled faintly of incense. Marble columns lined the open space of the nave, which was packed with the people of Rome. At the eastern end of the church, Charlemagne knelt before the pope. A tall man when standing, the Frankish king had an imposing presence even on his knees. He wore the dress of a Roman patrician: a tunic of multi-colored silk, embroidered trousers, and a richly embroidered cloak clasped with a golden brooch at his shoulder. As he knelt, the pope placed a golden crown, set with pearls and precious stones of blue, green, and red, on the king’s head. He stood to his full height of over six feet and the people gathered in the church cried out, “Hail Charles, Emperor of Rome!” The inside of the church filled with cheers. For the first time in three centuries, the city of Rome had an emperor. See Image 10.24.

Outside of the church, the city of Rome itself told a different story. The great circuit of walls built in the third century by the emperor Aurelian still stood as a mighty bulwark against attackers. Much of the land within those walls, however, lay empty. Although churches of all sorts could be found throughout the city, pigs, goats, and other livestock roamed through the open fields and streets of a city retaining only the faintest echo of its earlier dominance of the whole of the Mediterranean world. Where once the Roman forum had been a bustling market filled with merchants from as far away as India, now the crumbling columns of long-abandoned temples looked out over a broad, grassy field where shepherds grazed their flocks. The fountains that had once given drinking water to millions of inhabitants now went unused and choked with weeds. The once great baths that had echoed with the lively conversation of thousands of bathers stood only as tumbled down piles of stone that served as quarries for residents who looked to repair their modest homes. The Coliseum, the great amphitheater that had rung with the cries of Rome’s bloodthirsty mobs, was now honeycombed with houses built into the tunnels that had once admitted crowds to the games in the arena. And yet within this city of ruins, a new Rome sprouted from the ruins of the old. Just outside the city walls and across the Tiber River, St. Peter’s Basilica rose as the symbol of Peter, prince of the Apostles. The golden-domed Pantheon still stood, now a church of the Triune God rather than a temple of the gods of the old world. And, indeed, all across Western Europe, a new order had arisen on the wreck of the Roman state. Although this new order in many ways shared the universal ideals of Rome, its claims were even grander, for it rested upon the foundations of the Christian faith, which claimed the allegiance of all people.

With this ceremony in Rome, Charlemagne became the Holy Roman Emperor and was king of a large part of Europe: France, Germany, Italy, Belgium, Holland, and Switzerland. He introduced new ideas that would unite the people under his rule and modernize language, currency, and measurements. This period is sometimes called the Carolingian Renaissance.

Little is known about the early life of Charlemagne, also known as Charles I and Charles the Great. We know he is the son of Pepin the Short who led an army into Italy, conquered land, and gave it to the pope. This land became the Papal States. Charles reigned from 768 to 814 and we think he was born about 742. He spent much of his life in military campaigns against the Lombards, Avars and Saxons, first conquering them and then requiring that they convert to Christianity and adopt the Nicene Creed or be put to death. We know he had multiple wives and mistresses and as many as 18 children. He was a big man, 6’3” tall, which is much taller than the average man of his time. He was an athletic man who liked to hunt and stay active.

We remember Charlemagne for his promotion of literacy during his reign. As mentioned earlier, during this time learning was promoted by the church. Monks learned to read and write and schools were supported in the scriptoria where they created illuminated manuscripts. But Charlemagne had very advanced ideas for his time. He brought learned men to his court at Aachen and gave them instructions to begin teaching his subjects. Some of the scholars called to work at Aachen were Alcuin of York (735-804), Theodulf, a Visigoth, Paul the Deacon, a Lombard, and Angilbert and Einhard who were Franks. Einhard was Charlemagne’s biographer and it from his writings that we know about the king’s life. Alcuin was Charlemagne’s tutor and was a grammarian and a theologian. He gave instructions for the church leaders throughout the land to set up schools and teach the children to read and write. The goal was to help his subjects to be able to read the Bible, sing the hymns, and have a better understanding of their Christian beliefs. Even Charlemagne learned to read and write as an adult, which was unusual for a king.

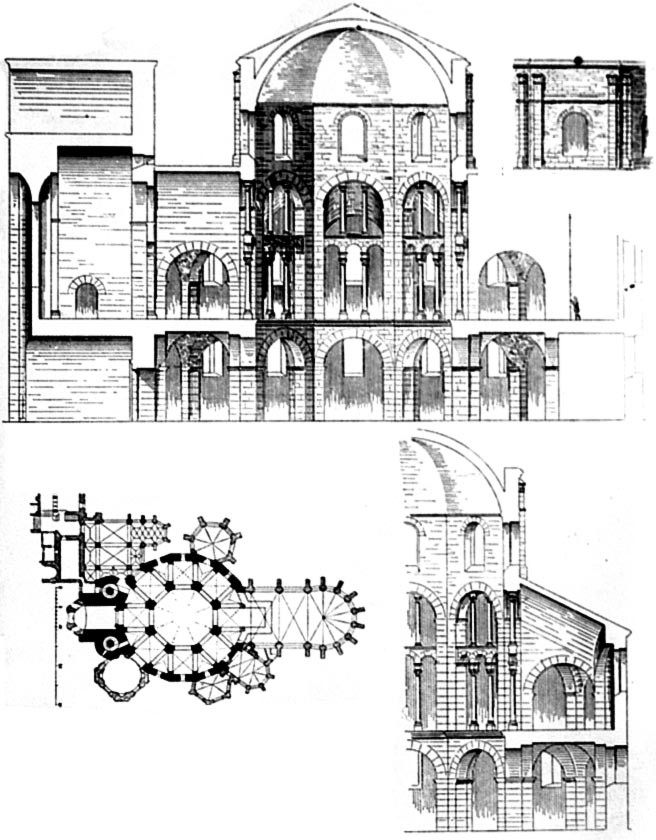

When Charlemagne went to the hot springs at Aachen, also known as Aix-la-Chapelle, he came to love the place. He ordered his church and palace to be built there and spent winters there to take advantage of the pools. He is known to have been a swimmer. The Palatine chapel was based on the Byzantine church at San Vitali in Ravenna. It is an octagonal church and has striped arches, an ambulatory, and mosaics on the dome above.

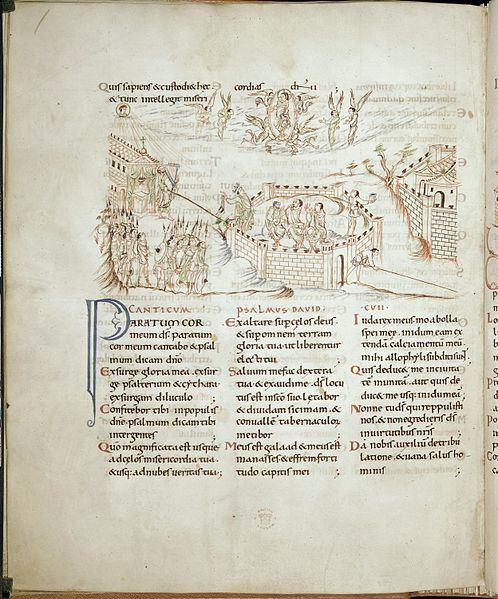

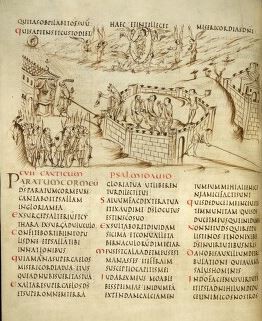

An important change made by Charlemagne’s court was the invention of a new type of writing. Until this time manuscripts were written in a script that used capital letters and did not have spaces between the words, making it difficult to read. The new style added spaces between the words and used lower case letters except for the first letter of a sentence. It also compressed the text and made it easier to read. Compare the two images below (See 10.29 and 10.30). Image 10.29 is Psalm 108 from the Utrecht Psalter made in 825 CE. Next to it is the same psalm from the Harley Psalter, written in 1010- 1030. The Utrecht Psalter became available to the scriptorium in Canterbury, where the monks copied it using the new script developed by Charlemagne and his scholars. This new type of text became the standard text used all over Europe and is the forerunner of our modern alphabet.

One of the campaigns Charlemagne fought became the focus of an epic drama. The real event occurred in 778 when Charlemagne’s army, led by his nephew Roland, was ambushed by Saracen Muslims as he returned from Spain. Roland’s men were betrayed by Ganelon, his own step-father, who revealed the route they would be taking through Roncesvals in the Pyrenees. Roland and his 20,000 men were then attacked by 400,000 Muslims and defeated. Charlemagne learned of the treachery and executed Ganelon, then went on to defeat the Muslim army. This story was passed down verbally and finally written down in 1100 as the Song of Roland, an epic drama that probably glazed over the facts. We know it from the singing of the jongleurs that traveled the countryside telling the “chansons de geste” far and wide to the strumming of their lyres.

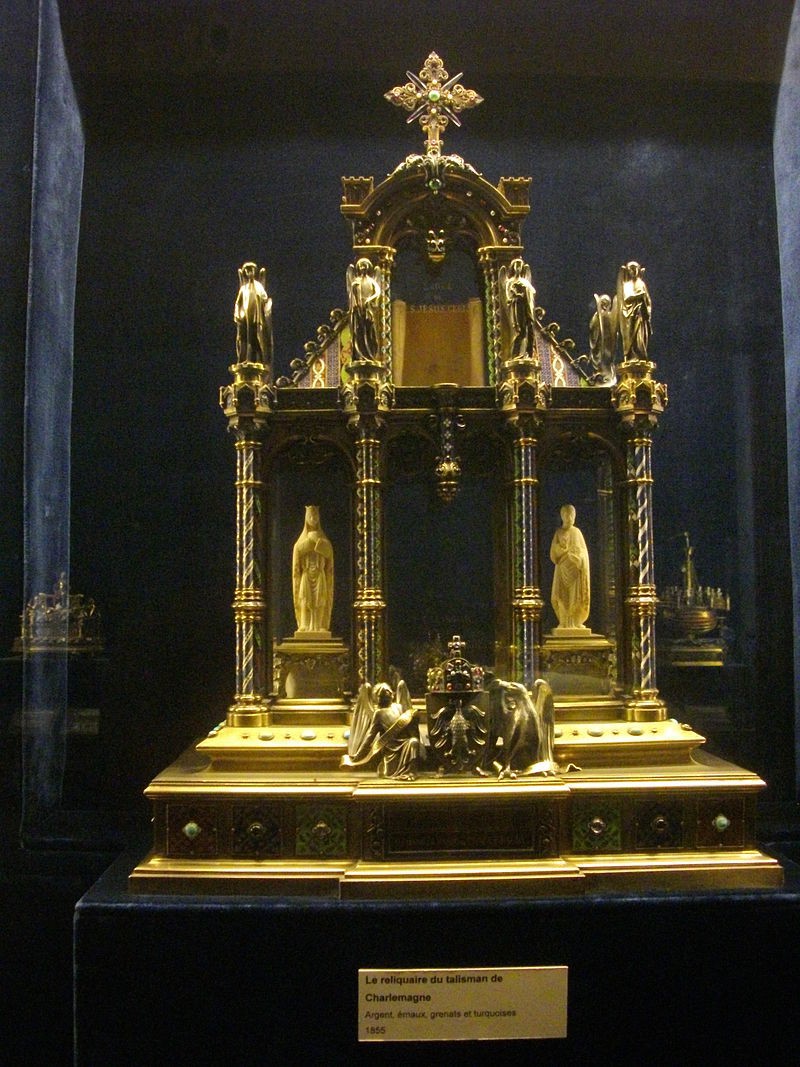

The Carolingian Renaissance spread a love of learning and new thoughts and ideas throughout Europe. Charlemagne even instituted a new currency when he did away with the gold sou and set a new standard using the livre, which was both a unit of money and weight. He also minted the denier as the coin of the realm. Charlemagne was buried in the choir of his beloved chapel after a short illness. Legends say that Otto III discovered and opened Charlemagne’s tomb and found him sitting on a throne, wearing a crown and holding a scepter. During the reign of Frederick I the tomb was reopened and the emperor was placed in a casket.

Attribution:

Berger, Eugene; Israel, George; Miller, Charlotte; Parkinson, Brian; Reeves, Andrew; and Williams, Nadejda, “World History: Cultures, States, and Societies to 1500” (2016). History Open Textbooks.

References:

1. Photo by Maximilianeum Gemalde. Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kaulbach_Die_ Kaiserkr% C3%B6nung_Karls_des_Gro%C3%9Fen.jpg

2. Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Portrait_of_Charlemagne_whom_the_Song_of_Roland_names_the_King_with_the_Grizzl y_Beard.png

3. Taken from Georg Dehio/Gustav von Bezold, Kirchliche Baukunst des Abendlandes. Stuttgart: Verlag der Cotta’schen 1887-1901, Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Aachen_Dehio_1887.jpg

4. Photo by CEPhoto, Uwe Aranas, CC BY-SA 3.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Aachen_Germany_Imperial-Cathedral- 12a.jpg

5. Photo by Fab5669, CC BY-SA 4.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Palais_du_Tau_-_Tr%C3%A9sor_(1).JPG

6. Taken from University of Utrecht Annotated edition. http://psalter.library.uu.nl/page?p=133&res=1&x=0&y=0

7. Anonymous, Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Harley_Psalter_-_BL_Harley_603_ psalm_ 108_f55v.jpg