10.1 Monasticism – Decline of Roman Influence

After the disintegration of the Western Roman Empire, chaos and confusion were left in its wake. The Romanesque age can be defined as the union of the older, settled Roman civilization with its ideas of reason, law, and order, and the spirit of the north with its restless energy. The Romans were urban and agricultural, built monumental stone architecture, had an organized legal system, were led by emperors and Caesars, and were literate. The barbarians were nomadic, bred pastured animals, built wooden forts with earthen walls, and lived in tents made of skins. Their government was based on a system of clans and kinship. Theirs was an oral tradition and they had few written laws. Roman roads and aqueducts were still in place, but there was no central government to repair or maintain them. Cities shrank drastically, and in those regions of Gaul north of the Loire River, they nearly all vanished in a process that we call ruralization. As Europe changed to a more rural culture and elite values came to reflect warfare rather than literature, schools gradually vanished, leaving the Church as the only real institution providing education. So too did the tax-collecting apparatus of the Roman state gradually wither in the Germanic kingdoms.

The Europe of 500 may have looked a lot like the Europe of 400, but the Europe of 600 was one that was poorer, more rural, and less literate. Without the protection of Rome the people were susceptible to invasion by the Muslims and other colonizing groups. Ever since the fifteenth century, historians of Europe have referred to the period between the fall of the Western Roman Empire and the Italian Renaissance (which took place in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries) as the Middle Ages. The term demonstrates that Europe was undergoing a transitional period: it stood between, in the middle of, those times that we call “modern” (after 1500 CE) and what we call the ancient world (up to around 500 CE). This Middle Age would see a new culture grow up that combined elements of Germanic culture, Christianity, and remnants of Rome. As Roman law and rule disintegrated, the void was filled by the only stable organization in existence: the Christian Church.

Bishops stepped in to consolidate power and take control. The abbey was one of the institutions that came to be extremely powerful during this time. Another term used by art historians to discuss this time period is Romanesque, due to the fact that it still relies on some of the ancient Roman ideas, now colored by Germanic and Christian beliefs.

LIFE IN THE MONASTERY

As the stability of Roman infrastructure disappeared, people lacked the security of city living, so they formed communities of devout Christians which flourished as havens of peace. These were called monasteries and they were miniature, self-contained worlds, which offered physical as well as spiritual safety. Another term for the monastery is the abbey, which was the center of monastic life. The monastery functioned as a religious shrine and may house one or many relics, depending on the amount of wealth it controlled. It was a manufacturing and agricultural center where monks or nuns spent hours in prayer and performed their assigned duties. They might also produce wine, ale, honey, cloth, grains or vegetables. The monastery was often the only source of medical care for the community, a hostel for travelers, and education. Many monasteries copied and illuminated manuscripts that could be sold. They were the “city of God” in physical form.

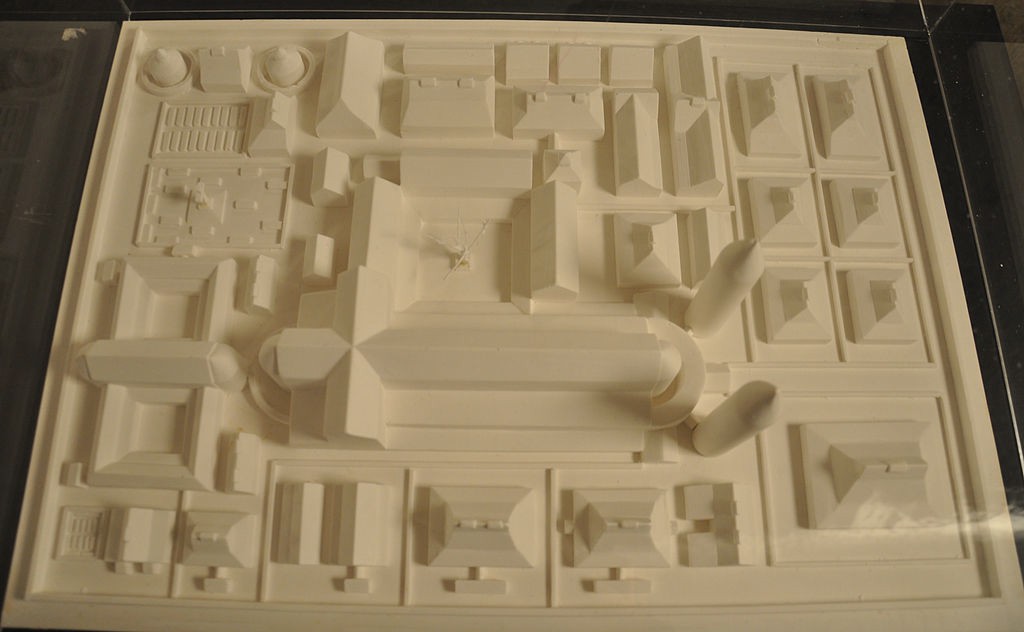

One such monastery was St. Gall. The plans were drawn in 817 CE and they are still in the library in a monastery in Switzerland. They were copied at least once because there are pin pricks in the margins of the vellum, but as far as we can tell it was never built. It was intended to be the plan of an ideal monastery.

This monastery has a residence for the Abbot, a school, and a hospice for distinguished guests. The quarters for the monks are on the side opposite the administrative buildings and the monks entered the church by the cloister or dormitory using stairs directly into the choir. The church is a basilica with a modular base of 2 ½ feet, which means that all parts are fractions of or multiples of 2 ½ feet. The width of the nave is 40’; the length of the monk’s beds is 6’3”and so forth. There is a prominent westwork, which is a façade placed on the west end of the church and includes a structure where the emperor was to sit if he came to visit. This follows the idea of the unity of church and state. There are multiple alters included so that many monks could officiate at the same time.

One of the main influences on monastic life was Saint Benedict. He grew up and was educated in the decaying imperial city of Rome and was probably able to see firsthand the growth of papal rule after Rome was sacked in 546. Benedict lived several years in a cave on the outskirts of Rome, where he taught and converted many pagans to Christianity. His greatest contribution was a written description of how monks should live and how the Abbot should rule his monastery. This is called the Rule of Saint Benedict. This way of life included strict rules that each monk who joined was committed to keep:

- Obedience without delay. Your action is acceptable to God only if it is done without hesitation, delay, grumbling or complaint.

- Silence: It is best to remain silent and you must have permission to speak. If you have to ask for permission you should do it with humility and then listen.

- Humility: a monk should climb the steps of humility until reaching God.

- Poverty: it is not necessary to have personal possessions and a monk should turn to the Abbot for all necessities.2

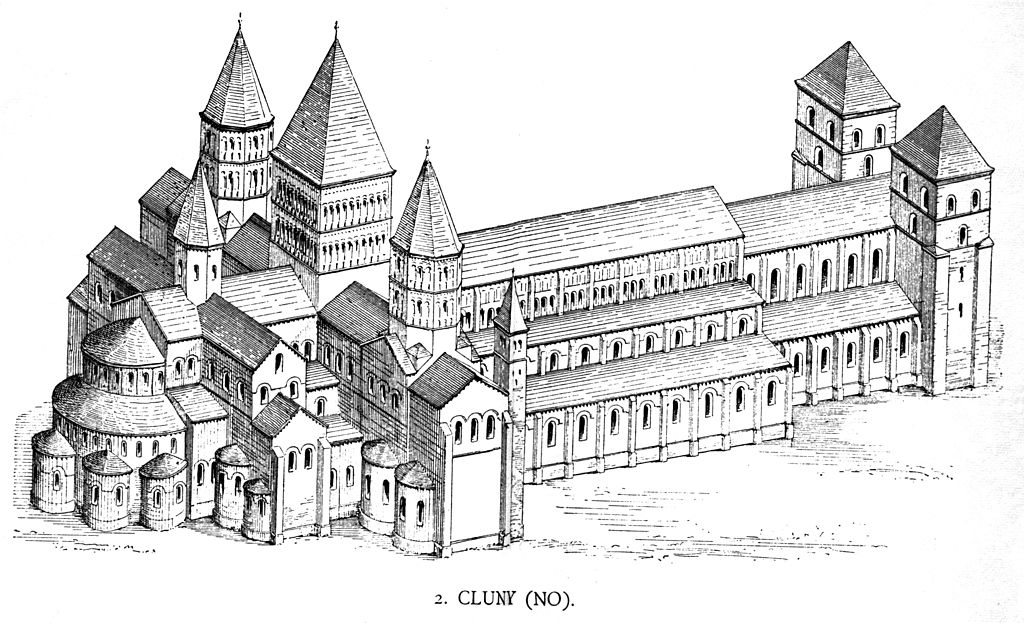

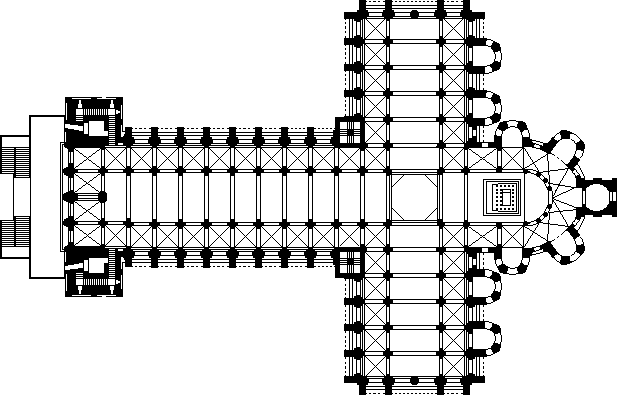

The largest and grandest of the Benedictine monasteries was the Abbey church at Cluny. In 909 William, Count of Auvergne and also Duke of Aquitaine gave the land and a Roman villa in Burgundian region of France to a group of monks who wanted to follow the rules of St. Benedict. The Abbey at Cluny was one of the most influential monasteries of the early Middle Ages. It became a powerful “mother house” to which others looked for inspiration. Monks from all over Europe wanted to serve and live in this monastery, so within 30 years after the foundation of the first church on the site, which we call Cluny I, it had outgrown its simple barn-like structure, so a new Cluny II was built. It was a basilica plan with a nave, a transept, and a tower and chapels at the east end. In 1088 a third church was begun, called Cluny III, which was dedicated in 1130. It was 555’ long, had double aisles and a double transept and was the largest church in the world until the new St. Peter’s basilica was built in Rome in the Renaissance. It had plenty of space for the monks in the choir, radiating chapels, an ambulatory, and an octagonal tower over the crossing. According to legend, St. Peter designed the church and appeared in a dream to instruct the architect, Gunzo.

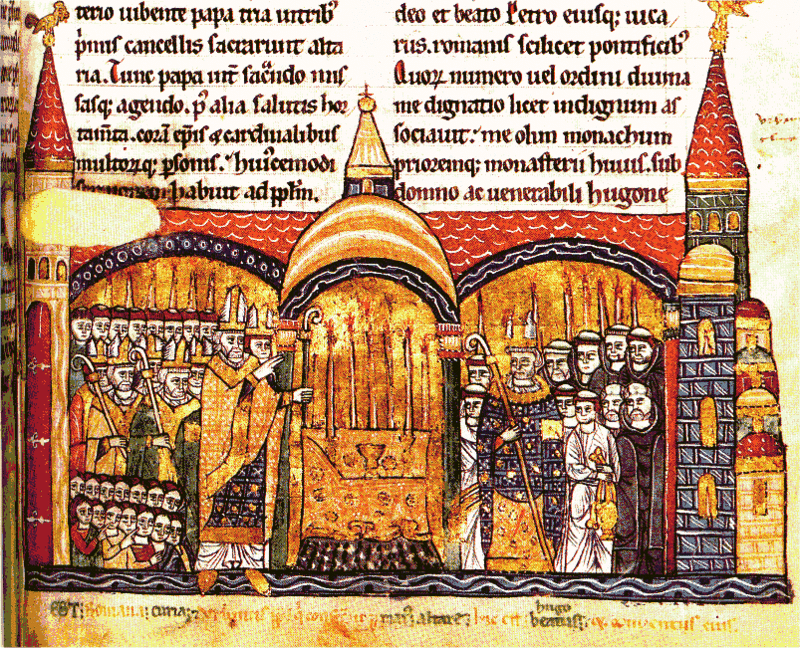

The magnificence of this church caused some to disapprove. New monasteries often copied the plan of Cluny, while others purposely built their new monastery to be plain and simple, as a protest against the extravagance of the grand building. Cluny stood until the French Revolution in 1798 when a wave of anti-clericism swept France and the abbey was sacked and burned. All but a single building was blown up with gun powder. There are illuminated manuscript depictions of the consecration of the main alter at Cluny III, see image 10.4, but all that remains of the building are some of its historiated capitals.

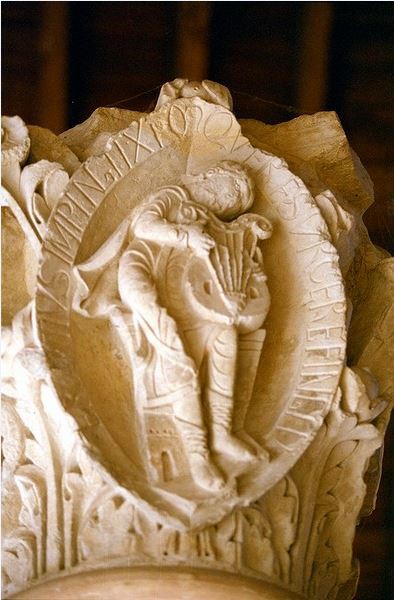

The capitals in Cluny III show the eight tones of sacred music. This capital shows the first tone of plainsong, with David playing his lyre to banish the devil and cast out the evil spirit in King Saul.

PILGRIMAGE

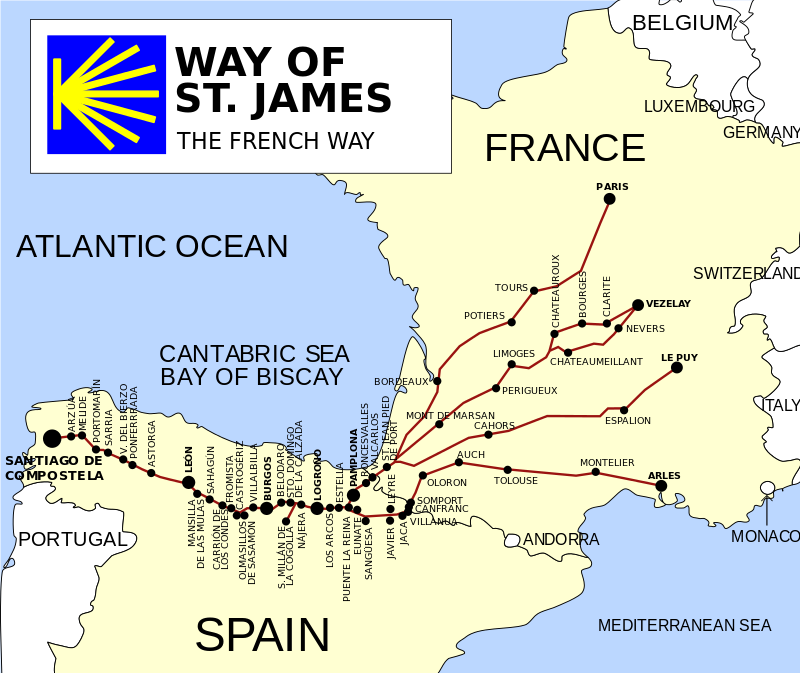

Another major influence on Romanesque life was the pilgrimage. In the 9th century CE the tomb of St. James the Apostle was discovered in Spain and by the 11th century it became a major destination for pilgrims seeking to be absolved from sin and to show their piety. The tomb of Santiago de Compostela was connected to Europe by four main roads which linked the important cities and unified the area. See image 10.6.

The roads were maintained by a guild of bridge builders and policed by the Knights of Santiago. In about 1130 a French priest, Aymery Picaud wrote a guidebook which is the Codex Callixtus. It is written for pilgrims and describes the route they should take and the most important shrines to visit along the way. See image 10.7 taken of the portal tympanum which shows the woman taken in adultery.

Picaud describes her this way:

“Nor must we forget to relate the woman standing beside the Temptation of Christ, holding in her hands the foetid (sic) head of her lover, cut off by her own husband, which, forced by her man, she kisses twice a day. What a great and admirable justice to an adulterous woman, to be told to all!”9

Pilgrims traveling along the routes to Santiago de Compostela and other pilgrimage churches, wanted to see the relics kept in each of the churches. The trade in relics was big business. In 326 CE Constantine’s mother Helena had traveled to Palestine to make an official inspection of the Holy Land and she brought back with her relics of the true cross, nails from the crucifixion and a tunic worn by Jesus before his crucifixion. Since that time churches, monasteries, and individuals have sought to own relics and have encouraged others to want to come view them and touch them too. It was believed that a relic could heal the sick and absolve the pilgrim from sin. A relic can include a part of the body of a saint or something that touched their body or was used by them. A community that had an important relic also gained major economic benefits from travelers who came and spent their money.

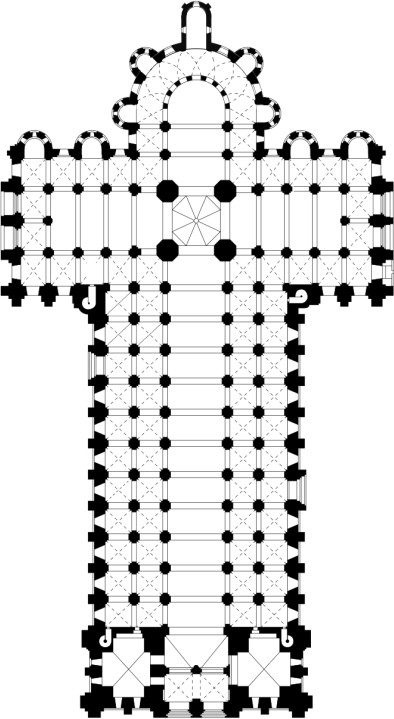

The intense communication between the cities along the pilgrimage route unified the architectural style of the churches they visited and the churches that were built in other areas of Europe. Stone masons and architects probably traveled these same roads and learned from what they saw. The church of Santiago de Compostela was a basilica plan with a transept that creates the shape of a cross and an ambulatory with radiating chapels that could house relics. Pilgrims were able to walk behind the main alter even if the mass was in progress. This was the basic plan of churches built all across Europe. Compostela was supported by rounded arches along the nave and small windows that let in very little light.

These churches needed to be able to accommodate large crowds, house and display the sacred relics, and allow the regular business of the daily office of the mass to proceed uninterrupted. In general pilgrimage churches were built with these basic characteristics.

- They were blocky and were a grouping of large, easily definable geometric shapes.

- The main sections were divided from each other by buttresses or colonnettes.

- The exterior wall surfaces reflect the interior organization of the structure.

- Care was taken to make the structures fireproof, well lit, and acoustically suitable to the music which was becoming more important in the mass.

- They were built large enough to house the growing population of the urban centers as well as the traveling pilgrims that passed through.

The church at St. Sernin Toulouse, built between 1080 and 1120 is an example of a church built like the one at Santiago de Compostela. The basilica plan forms a Latin cross, the aisles take the pilgrim in a traffic pattern around the main alter to the radiating chapels with their relics. It is a near copy of the church in Compostela. It is made of masonry throughout to lessen the chance of fire. The rounded vaults along the aisle carry the thrust of the ceiling to massive outer walls which are strengthened by buttresses. It looks blocky, severe, grand, and fortress-like. The entrances are practical, allowing many people to enter and exit quickly. The sculpture is impressive and was made to indoctrinate the pilgrims.

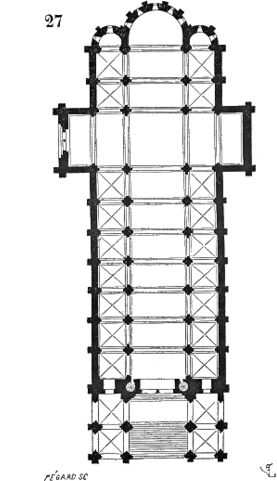

The cathedral at Autun, Saint-Lazare follows the same rules. It was originally built to house the relics of Lazarus, the brother of Mary Magdalene, who was raised from the dead according to the story in the New Testament. The bones of Lazarus were discovered in the 12th century and this church was built to house this important relic.

One of the most important things to study at Autun is the amazing sculpture created for it. This is one of the few times that we actually know the name of the man who carved the capitals for a cathedral. His name was Giselbertus, a French sculptor who was active in the 12th century. Giselbertus carved his name on the bottom of the Last Judgment Tympanum with the permission of the Bishop of Autun. We know little of his life, but we think some of his work is also in the Abbey of Cluny where he worked as an assistant to the master sculptor there. His work is some of the most original sculpture we have from this time.

This is the story of the Last Judgment of Christ, with those worthy to return and be with him standing with the angels on his right, and the damned in the company of the devils on his left. Think of the realistically portrayed soldiers on Trajan’s column, image 6.47, and compare them to these tall unreal soldiers and enemies of Christ. The entire scene is symmetrical, with Christ in the center. He is elongated, frontal, and seems to be on a different plane. His limbs are twig-like, the draperies cling, but the body does not seem to have any substance. His feet do not seem to stand on anything real, and it is as if he is floating above the door. He floats in a halo above a replica of the City of God. The beings on his right live in a world of order, peace, and calm. The Virgin Mary sits enthroned near the top along with some of the souls who now live in heaven. The demons on Christ’s left surround Michael, who weigh’s the souls of the dead to see if they are worthy to enter heaven. Notice that the demons try to tip the scales in their favor so they can get more souls into hell. An inscription at the bottom reads, “may this terror terrify those whom earthy error binds.” The humans in the lintel below are just rising from their tombs and they seem to cower in fear as they realize what could happen to them. Demons even snatch naked victims and pull them into frightening world. See image 10.19 and image 10.20. Images like this were like sermons in stone. Count to the 16th fellow at the bottom of the lintel, under the word “Lucerna” and notice that he is a little more confident as he approaches judgment: he has a shell on his pocketbook boasting that he has been on pilgrimage.

Gislebertus’s Eve also show’s his innovative imagery. See image 10.21. Eve originally floated over the south exterior portal of the cathedral and warns all who enter that they are human and have fallen from God’s grace. She is licentious, sensuous and seductive and moves through the Garden of Eden like a serpent. Her left hand picks fruit from a branch on the forbidden tree, which has been pushed toward her by the serpent. She is in a position of penance: stretched out on the floor supported by knees and elbows. Images like this must have terrified those who saw them, but this was the standard way to show how women and other “lesser” beings must be humbled.

Giselbertus created many historiated capitals. These are but two: the Suicide of Judas and the Flight into Egypt. Note the deeply carved mouths of the dead Judas and the devils that are glad to have him. In fact they are pulling on the rope around his neck to be sure he doesn’t change his mind. The Flight into Egypt shows Mary on the donkey and Joseph leading them to safety away from Herod’s murdering guards. Mary has her arm around the young child Jesus, but she hardly seems to be holding him at all. The position of this capital shows them moving intentionally from darkness into the eastern light.

A discussion of the Romanesque age is not complete without a discussion of Asceticism. The monastic way of life demanded seclusion and escape from the cares of reality and the severity of monastic life stimulated the imagination. The Rule of Saint Benedict required that a person attain a high spiritual and moral state by obedience, silence, humility, and poverty. Turning away from the world is expressed in plain exteriors and rich interiors showing that the inside of a man is more important than what he looks like outside. Arts were not intended to mirror the natural world, but to conjure otherworldly visions and aspects of the world beyond. Artists used elaborate symbolism which was addressed to the educated, cloistered community familiar with sophisticated allegories. Although the sculpture found in Romanesque cathedrals was certainly visible to the masses and was intended to be instructive, many Romanesque monastic works were intended to relate to the intense inner life and visionary focus of the religious community that the lay person would not understand.

Think about the Classical Greek and Roman sculptors who conceived the gods as human in form. Since the Christian god was more abstract, so were the representations of Him. Rational proportions were of no use. God was to be felt through faith rather than comprehended by the mind. Life was oriented by deep religious convictions, and those models could not be found in the real world. So architecture was built with fantastic proportions. The human body was distorted. See 10.19. Manuscript illumination revolved around elaborate initials. See 10.53. There were ornate melismas in music. The most admired book of the Bible was Revelations. More real to the monk were the things of the other world. He had never seen them, but they were real to him.

You may also enjoy the following links to additional media information:

Attribution:

Berger, Eugene; Israel, George; Miller, Charlotte; Parkinson, Brian; Reeves, Andrew; and Williams, Nadejda, “World History: Cultures, States, and Societies to 1500” (2016). History Open Textbooks.

References:

1. Photo by WolfD59. Public Domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:St_Galler_Klosterplan_Modell_2.jpg

2. https://christianhistoryinstitute.org/study/module/benedicts-rule/

3. Georg Dehio/Gustav von Bezold, Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dehio_212_Cluny.jpg

4. Photo by LeZibou, CC BY-SA 3.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File: Cluny_abbey_ main_transept_ south_ 01.JPG

5. Odon de Cluny Bibliotheque de France. Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File: Cons%C3%A9 cration_cluny.png

6. Epierre at French Wikipedia,CC BY-SA 1.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:FR-Cluny-Abbaye-2643-0036.jpg

7. Photo by Vivaelcetta, CC BY-SA 3.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:French_Ways_of_St._James.svg

8. By Yearofthedragon, CC BY-SA 3.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File: Spain.Santiago.de.Compostela.Catedral. Puerta.Meridional.001.jpg

9. https://sites.google.com/site/caminodesantiagoproject/home

10. Photo by Heilfort Steffen, CC BY-NC-SA 3.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Arles-Kathedrale_St.Trophime_1078- 1152_Reliquien-Benannt_nach_dem_ersten_Bischof(3.Jh.n.Chr)vonArles-Innenraum-.JPG

11. Photo by Jose-Manuel Benito-Public Domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Santiago-Catedral-Planta.gif

12. Photo by Miguel Hermoso Cuesta, CC BY-SA 4.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File: Interior_catedral_ Santiago_08.jpg

13. Photo by Lansbricae, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File: Catedral_de_Santiago_de_ Compostela_interior_adjusted.JPG

14. Photo by Lancastermerrin88 CC BY-SA 4.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File: Nave_derecha_de_la_ Catedral_ de_Santiago_de_Compostela.JPG

15. Photo by Didier Descouens CC BY-SA 4.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Basilique_Saint-Sernin_de_ Toulouse_-_exposition_ouest-1-.jpg

16. Photo by JMaxR, CC BY-SA 2.5. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Plan-st-Sernin-Toulouse.png

17. Photo by Jose Luis Bernardes Riberio, CC BY-SA 3.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Nave_-_Basilica_ of_ St_Sernin_-_Toulouse_-_France_2014_(2).jpg

18. Photo by MarcJP46. CC BY-SA 3.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Autun_BasiliqueStLazare03_JPM.JPG

19. Dictionary of French Architecture from 11th to 16th century, Public Domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File: Plan.cathedrale.Autun.png

20. Photo by PMRMaeyaert, CC BY-SA 3.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Autun,_Cath%C3%A9drale_Saint-Lazare_PM_48356.jpg

21. Photo by Gaudry, Daniel. CC BY-SA 3.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Autun_saint_lazare_tympan_01.jpg

22. Photo by Gaudry Daniel, CC BY-SA 3.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Autun_saint_lazare_tympan_18.jpg

23. Photo by Cancre CC BY-SA 4.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Autun,_Gislebertus,_Eva.JPG

24. Photo by Cancre, CC BY-SA 4.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Autun,_Judas.JPG

25. Photo by Christophe.Finot, CC BY-SA 1.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Autun_chapiteau_3.jpg