8.4 Justinian, Master of Three Powers

Basilica of San Vitale, Ravenna

After Constantine himself, the Emperor Justinian I is the most prominent individual in the history of the Western Roman Empire. In 527 Justinian had just begun his reign in the Eastern part of the Empire and was desirous of also reclaiming the lost western-half of the historical Roman Empire. With a similar intent to that the proclamation made by Constantine’s colossal statue at the Basilica Nova,2 Justinian wanted a fail-safe demonstration of his power. As an exemplification of that authoritative power, the exclusivity of Orthodox theology would be of primary importance.

Justinian adopted the project to make sure that this city, the sedes imperialis (Imperial seat) of the Western Roman Empire, would be worthy of the glorious ritual which would demonstrate his authority. His power was proclaimed in Ravenna not with a triumphal arch or colossal statue, but with this remarkable basilica.3 His ultimate objective would be met at this location: all would recognize his proud mastery of three types of power: political, military and religious.

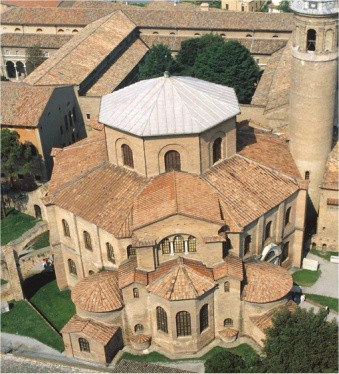

The building of the Basilica of San Vitale [image 8.63] had probably been begun by Ecclesius, the Orthodox bishop in Ravenna, the year before Justinian’s reign commenced. In 524 the bishop had visited Constantinople with Pope John I. While there he had been stunned by Byzantine buildings, both new and old, and returned to Ravenna filled with inspiration. The location was auspicious: archaeological excavations have revealed the remains of a small fifth century chapel with mosaic floors. That site was had perhaps been consecrated to St. Vitalis (San Vitale), a local soldier from the first, or possibly fourth, century who was said to have undergone various tortures to make him abjure his faith. Finally the martyr was thrown in a ditch and stones and dirt were heaped upon him. According to the tradition repeated in Ravenna, Vitalis and his wife Valeria were the parents of Milanese martyrs Gervasius and Protasius.4 Adhering to the Roman tradition of “pater familias” the rank of father held precedence over the sons; therefore, Ravenna, home of the father, held a higher status and was more “deserving” of being the western sedes imperialis than Milan.

The now soggy floor of the old chapel is 27.5 inches (70 centimeters) below the floor of the present basilica of San Vitale and is today covered by ground water [image 8.64]. The hole in the floor of San Vitale isn’t much to look at, but the political status of Ravenna and the relics of the saint made it a faithworthy justification for a centrally-planned building overlaying the former chapel, in the popular style then being built in Constantinople.

Adding to its prime-real estate status, the chapel was adjacent to the magnificent Mausoleum of Galla Placidia [image 8.65].7 The Mausoleum had not been built around a relic but it did have an inspirational stellar dome. (Not incidentally, because of subsidence the floor of the Mausoleum had been raised 56 inches (1.43 meters) in the sixteenth century. We should be grateful anything is still standing in Ravenna!)

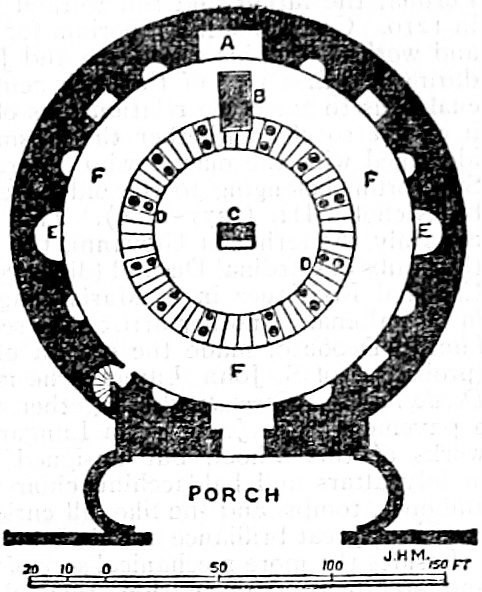

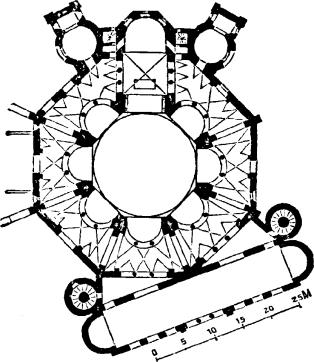

The specific inspiration for San Vitale may have come from several sources, but these aerial perspectives [images 8.66 and 8.67] encourage us to appreciate the unique similarity of the central plans of Santa Costanza8 in Rome and San Vitale in Ravenna. The axis of both structures is up toward the central dome.

Both buildings were formed by two concentric rings which designate a circular ambulatory [images 8.66 and 8.67]. San Vitale adds further symbolism to the annular vault with an eight-sided octagon. The central octagon is looped by seven exedrae (semi-circles) which suggest God as an infinite power which expands in all directions. The eighth exedra opens into the sanctuary, which ends in an eastwardly projecting apse that reaches up into the second story gallery area. The central octagon is surrounded by a second octagon, which forms the second story ambulatory. The 197’ tiburum (lantern tower) is above the central octagon [image 8.68]. It, too, is a symbolic eight-sided octagon. On the west side is the narthex, through which we have entered.

As we approach the nave we are encouraged to “Look up! Look forward!” That has been a recurring refrain ever since we arrived in Ravenna. Here elongated Roman arches, in double arcades, lead to vaulted semi-domes, then more arches, and then the central dome. The overwhelming changing patterns of light, reflecting off of sparkling glass tesserae and polished marble, were very intentional. It is likely that glass windows originally captured that light from every direction; these, reset in 1904, are an alabaster imitation.

Mystical configurations in support of Orthodox theology are all around us [image 8.70]. The tiburum (lantern tower) is eight sided, like the nearby baptismal fonts.14 Eight windows, symbolizing infinity, emphasize the octagonal shape. The apse has two levels, symbolizing heaven and earth. The apse also has three windows which is just one of several references to the Trinitarian fervor to be seen in this church.

The apse mosaic illustrates the Second Coming [images 8.71]. A beardless Christ is wearing a purple tunic with a broad golden stripe (clavus) and sitting on a blue globe. Christ’s head is surrounded by a halo in which we see a jeweled cross. The gold background suggests this is a heavenly scene which is complimented by the Four Rivers15 flowing out of Paradise. In his left hand Christ has a scroll with the seven seals of the Apocalypse from the Book of Revelation.16 In his right hand he is acting like a Greek Nike as he extends the martyr’s crown to the local hero, St. Vitalis. Because this is a timeless and eternal event, Christ will forever be honoring his followers.

Christ is flanked by two winged angels. The angel on our left has his hand on Vitalis’ shoulder, introducing him to Christ. The angel on the right introduces Ecclesius, the Orthodox bishop of Ravenna, who is presenting a miniature model of his project, this very church, to Christ. While the church had been started in 526, most of the construction probably occurred after the Justinian’s reconquest of Ravenna in 540. Byzantine workmen, materials and the most up-to-date architectural ideas would have poured into the Classe’s ports from Constantinople and the east, along with innovative ideas in mosaic artistry.

In the apse we see a youthful Christ. Look above you at the triumphal arch and into the vault [images 8.72 and 8.74]. There are, in this sanctuary area, a total of three representations of Christ. Can you find them?

In the vault over the apse is another clear demonstration of the perfection of Trinitarian thought. You may recall the completeness of “27” as a derivative of three times three times three (3 x 3 x 3=27). Look around; can you find the superlative example of 27?

In Trinitarian fervor, the three appearances of Christ portray him in three different stages:

- Young (and beardless) [image 8.71].

- Mature (bearded) [images 8.72 and 8.73].

- At the Second Coming as the Agnus Dei, the mystical and glorified Lamb of God [images 8.74, 8.75]. These three representations are a message to the community of Ravenna, and to all of western Rome, “Hark Arians (and Montanists, Nestorians, Docetists, Marcionites, Monophysites, Gnostics and everybody else) all three bases are covered. Christ is youthful and mature, physical and mystical. He is always regal while simultaneously being the ultimate sacrifice.”

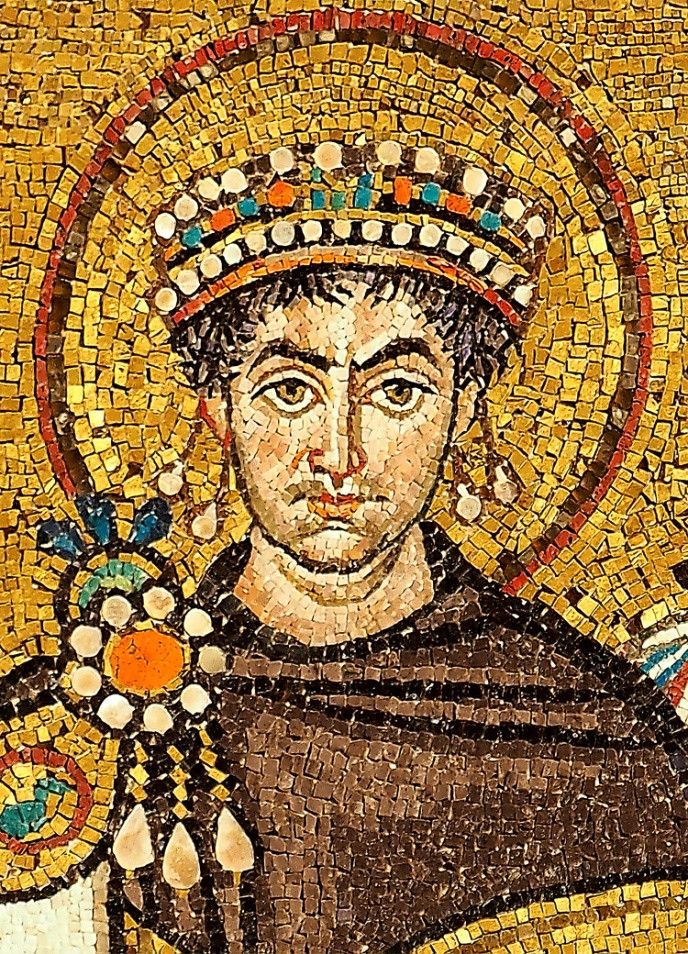

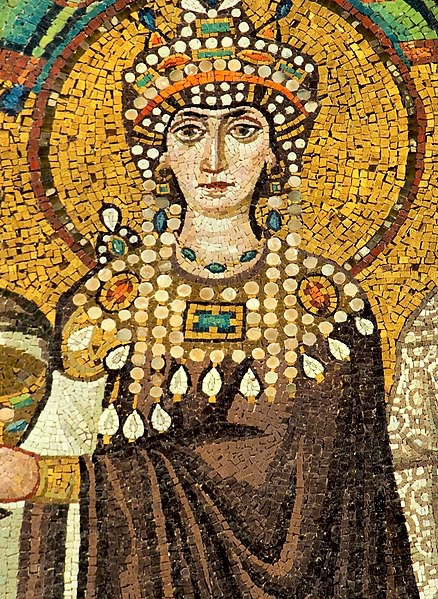

Returning to the apse, the architect, Isidore of Miletus (also the architect of the remodeled Hagia Sophia24) would have us follow the direction of movement from the crown that was being passed to Saint Vitalis [image 8.76]. Our line of sight goes to the Emperor Justinian on the left side of the apse [image 8.77], and then straight across the apse to his equal, the Empress Theodora [image 8.79].

If the apsidal conch suggests the heavenly court, the images on the lateral walls are middle level. Here we witness the emperor (and the dignitaries) mediating between God and the people. You might have already guessed it: there is a level at the base where we, the populace, gather.

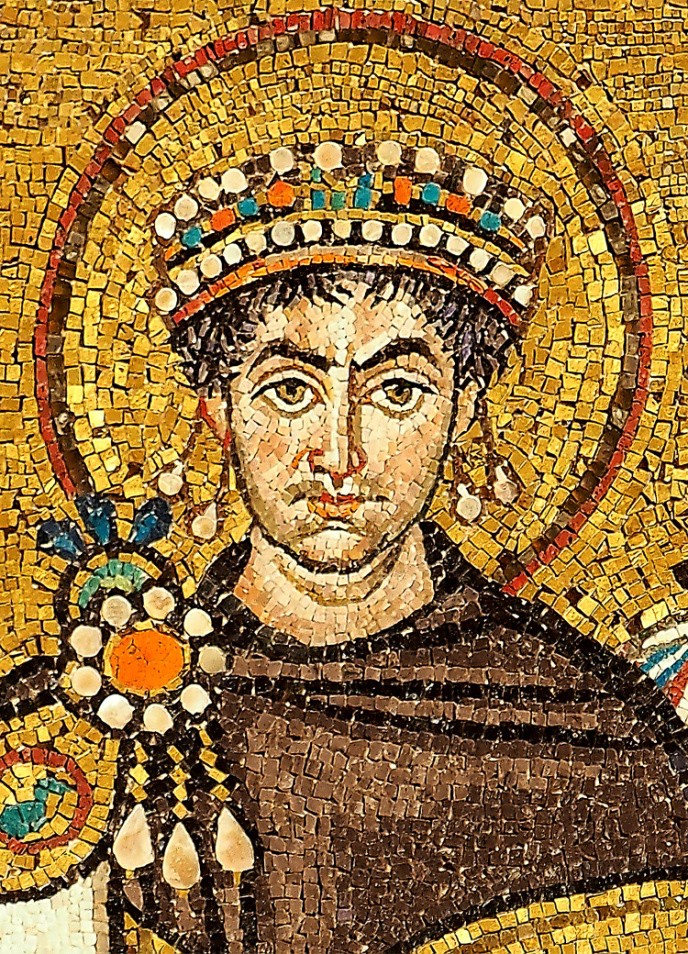

The most famous mosaics at the Basilica of San Vitale are these apse portrayals of Justinian and Theodora and their courtiers. Emperor Justinian (b. 482) was not well educated, but he was a successful military commander with a sure grasp of imperial administration, law and theology. The depictions of Emperor Justinian and the Empress Theodora on the north and south walls of the apse were celebrations of a church ceremony rather than a depiction of a specific event.

Justinian is offering the paten (a shallow metal plate used to carry the communion bread) while Theodora is presenting the chalice (the cup for the communion wine). The royals personally never visited Ravenna, but they had a thorough understanding of court ceremony and they wanted their subjects to remember them as being perennially present in Ravenna.

Justinian’s authoritarian attitude dominates image 8.82 just as he dominated the times. An examination of the symbols used in this mosaic leads to an understanding of Justinian’s claim of military, political and religious power. His military power is presented by the honor guard of soldiers who are intentionally displaying the Chi-Rho monogram which had been adopted by Constantine. Gold torques at their necks identify them as barbarians. Their commander, General Belisarius, was Justinian’s right hand man. He led the campaign to retake Italy from Arian heresy, but look at Justinian’s right foot [images 8.82 and 8.84]. Breaking the barrier between heaven and earth he held even General Belisarius under his control.

Justinian’s political power is proudly proclaimed by his imperial purple tunic. He boasts a large brooch on his right shoulder; no simple clavus for this emperor. His purple mantle is complimented by a golden rectangular inset, a tablion, which is lavishly decorated with figures of birds. Take note of his red and purple shoes, ornamented with pairs of pearl pendilia. Only the emperor may wear such finery.

Justinian is not turned to face Christ. Because he is like unto a god himself, he is presented to the viewers from a frontal position. The Emperor is in good company with Bishop Maximianus, the only man identified by name. Maximianus became Archbishop (second only to the Pope) about the time of the completion and consecration of the church. He is wearing a chasuble, with the bishop’s pallium draped over his shoulders. His white omophorion which was embroidered with crosses further confirms his identity. He is holding an ornate cross in his right hand. On the far right were two deacons. One carries the Bible while the other has an incense burner.

Sliding in slightly behind Justinian and the Archbishop Maximianus is possibly the banker who subsidized this church as well as several other projects under the rule of Justinian, Julianus Argentarius. Why was he tucked away? Perhaps he was added later, or perhaps those who handle money were seen as somewhat untrustworthy, even if he contributed 26,000 gold solidi for this project. We do not know the identities of the other individuals, but perhaps they were recognizable to their contemporaries.

Even if all the other members of the court were not depicted, the distinctive appearance of Justinian alone would be memorable [image 8.82]. San Vitale was constructed during Justinian’s long reign (527-565) and there was no other emperor during that period, so even though his image doesn’t look anything like other portrayals of him, it must be him. His large, wide-open eyes exemplify the mystery we saw in Faiyum portraits,31 as well as the godlike gaze of Constantine on his Colossal Statue.xxxii With those eyes he could serve as a model example of Matthew 6:22, “With the pure eye one sees God.”

All of his subjects would have recognized the symbolism of the halo, which only he wears. The Egyptian god Anubis had been symbolized with a lunar disk on his head, Roman emperors wore halos and saints were honored with halos. Like Hammurabi, Justinian claimed to be serving by divine right and his tenure of 40 years on the throne was thought to have confirmed that right. Like Alexander the Great he saw himself as Divine, Heroic and a natural Leader. Justinian claimed descent from Julius Caesar and he promoted the Cult of the Emperor, as Augustus Caesar did for his great-uncle Julius Caesar. And, in similar fashion to Constantine, he ruled as the “equal of the apostles.” He was the visible manifestation of God.

Justinian was creating a tradition that was to last for all of Byzantine history: that of the emperor being both the spiritual leader of the Christian church and the political/military ruler of the empire itself. Bishop Eusebius of Caesarea (d. 339) had succinctly stated the Theo-political doctrine, “In as much that Jesus was prophet, priest and king so should the Christian Emperor hold all ranks.” Granted, this statement had been made two centuries before Justinian’s rule, but we may imagine the emperor exclaiming, “Works for me!” Justinian believed there should be a symphonia of church and state, a harmony and concord based on the incarnation of the divine Logos (reason, the word of God) and the man Jesus. Just as the two natures (divine and human) were found in the single person of the Christ, there should be no separation of the church and the empire; together they formed the Kingdom of God, which would soon spread to the entire world. For Justinian, the halo and the crown declared his divine kingship.

At first glance his crown appears fairly standard, but what is with those dangling “earrings?” Perhaps the style of his crown was similar to this crown which was found near Toledo, Spain, in 1858 [image 8.85]. Visigoth kings are known to have consciously copied Roman customs and ceremonies, including written law and victory parades. This diadem has been identified as the Votive Crown of King Recesswinth who ruled in Spain between 653 and 672. The diameter of the crown is 8 ½” so it could have been worn. Votive crowns were hung above the altar, indicating the emperor’s piety and ecclesiastical authority. Perhaps this was buried (hidden) during the Arab conquest of Iberia in 711 and not discovered until the nineteenth century.

As depicted on this mosaic, Justinian seemed to have it all together. But, another story was told by Procopius of Caesarea who was secretary to General Belisarius. He had been commissioned by Justinian to write an official history of Justinian’s wars and an entire volume praising his building accomplishments. On the side Procopius also wrote a private memoir, the Anecdota (Secret Histories) which was not published during his lifetime. The scummy writings (which could have been copy for a twenty-first century tabloid) were discovered in Rome in the seventeenth century.

I think this is as good a time as any to describe the personal appearance of Justinian. Now in physique he was neither tall nor short, but of average height; not thick but moderately plump; his face was round and not bad looking, for he had good color even when he fasted for two days…Now such was Justinian in appearance, but his character was something I could not fully describe. For he was at once villainous and amenable; as people say colloquially, a moron. He was never truthful to any-one, but always guileful in what he said and did, yet easily hoodwinked by any who wanted to deceive him.37

Empress Theodora was treated much more graciously by Procopius. “Theodora was fair of face and of a graceful, though small, person; her complexion was moderately colorful, if somewhat pale; and her eyes were dazzling and vivacious.”38

Theodora was born in 497 and married Justinian in 525. Little is known about her early life and the rumors that surround her make for titillating reading. She was, perhaps, the daughter of a bear keeper at the circus, a circus performer, a child prostitute, an actress, a pantomime artist, or a wool spinner. Whatever, Justinian was smitten and married her against the advice of his uncle, the Emperor Justin I. It was a fortunate decision; Theodora’s intelligence and political acumen made her Justinian’s most trusted adviser. When Justinian succeeded to the throne in 527 she was proclaimed Augusta (co-emperor) and received a crown, as well. Along with her husband, she is a saint in the Eastern Orthodox Church, commemorated on November 14.

The Empress participated in Justinian’s legal and spiritual reforms, and her involvement in the increase of the rights of women was substantial. She had laws passed that prohibited forced prostitution and closed brothels. She created a convent on the Asian side of the Dardanelles called the Metanoia (Repentance), where the ex-prostitutes could support themselves. She also expanded the rights of women in divorce and property ownership, instituted the death penalty for rape, forbade exposure of unwanted infants, gave mothers some guardianship rights over their children, and forbade the killing of a wife who committed adultery.

In this ecclesiastical ceremony [image 8.86] Theodora is presenting a golden chalice (for the communion wine). Strictly speaking, Theodora and the other ladies were not supposed to be in the sanctuary at all, so the two figures on the left may be eunuchs, lifting the curtain for the ladies to enter the stairway that will take them to the second story gallery. The ladies on her left are thought to be General Belisarius’ wife as well as Theodora’s friend and confidante, Antonina, and then the General’s daughter, Giovannina. The other women are unidentified, but again, perhaps they would have been recognizable to a contemporary audience. A court official is almost at the right hand edge.

We pause to ponder: how did the artists, who had never met Theodora, make an image that conveyed royalty, dignity, and luxury [image 8.86 and 8.87]?

- Like the Emperor Justinian, she is the only one with a halo.

- She is isolated and silhouetted from the background in the technique known as fondo d’oro.40

- She is taller, and her long neck supports an elaborate crown.

- She wears a tiara of simulated emeralds, diamonds and sapphires with pearl pendilia.

- Her narrow emerald necklace and dangling emerald earrings have pearl and sapphire pendilia.

- She wears a brocaded cloth rather than a Roman toga.

- She stands under an umbrella-shaped canopy (variously known as a fastigium, ciborium, aedicule or baldachin).

- She stands near a classical Greek column.

- Similar to a Classical Greek kore, her face is expressionless; she shows no emotion.

- The striking beauty of Theodora may be compared to Platonic and neo-Platonic philosophy: beauty in this world is symbolic of the divine world.

At the bottom of her brocaded chlamys [image 8.88] is another example of the Trinitarian fervor which we have often seen around Justinian’s Ravenna. As we observed at Sant’ Apollinare Nuovo, the Magi are recognized by their outlandish dress, short cloaks, peaked caps and leggings43. All of these are indicators that they are foreigners paying the customary tribute, the aurum coronarium, in acknowledgement of the mastery of the Roman Empire. And why are there three? According to Andreas Agnellus, the ninth century author of the Liber Pontificalis, “The three precious gifts contain divine mysteries, namely gold signifies royal power, incense represents the priest, and myrrh indicates death, to underscore the fact that it is Christ who has drawn unto himself all the wickedness of mankind. And why did precisely three wise men come from the east, instead of four, six, or two? To signify the perfection of the entire Trinity.”

It might be argued that the city on the Bosporus which had taken the name of the 667 BCE Greek colonizer Byzas had abandoned Greek traditions. Pythagorean proportions, memorable capital styles and democratic government seem to have subsided into the marshland. Significantly, however, the Greek cultural value of Idealism pushed on. Idealism was advanced in the writings of Plato and was carried forward by the neo-Platonists who strongly influence Christian thought. Idealism is the value respected by depictions of both the kouros and the martyrs. And it was important to the Emperor Justinian. In his attempt to bring perfect unity to the Empire he promoted the Justinian Code. Ten legal experts and 39 scribes led by the great legal expert Tribonian systematized the previous 900 years of Roman law into a rational, precise and comprehensive code of 4,652 clear and consistent laws. Formally known as the Corpus juris civilis, it was claimed that 3,000,000 lines of jurisprudential law had been reduced to 150,000. It was used as a basis for Byzantine law for over 900 years, and the laws therein continue to influence many western legal systems to this day.

You might appreciate this video about the Basilica of San Vitale (11:45):

https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/ap-art-history/early-europe-and-colonial-americas/medieval-europe-islamic- world/v/justinian-and-his-attendants-6th-century-ravenna

References:

1. Dr. Allen Farber, “San Vitale and the Justinian Mosaic,” in Smarthistory, August 8, 2015, accessed October 25, 2019, smarthistory.org/san-vitale/

2. See Hartman, Kathleen J. “Chapter 7, The Ambition of Constantine.” Humanities: New Meaning from the Ancient World. Colorado Springs, CO: Pikes Peak Community College, 2020. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

3. Before the legalization of Christianity, the basilica was a sheltered public hall off the forum. By the sixth century the word was used to designate the status of a church, not the form. This is a centrally-planned building.

4. Saint Vitalis was believed to have been martyred either during the first century under the reign of Nero (54-68) or in the fourth century under the reign of Diocletian. Both Vitalis and Valeria as well as their sons, Gervasius and Protasius are among the identified martyrs at the Basilica of Sant’ Apollinare Nuovo. Images of their sons, Gervasius and Protasius, are also on the triumphal arch in the Basilica of San Vitale.

5. Public domain at search.creativecommons.org/photos/87e2545b-84d3-42ea-8084-4f0188a09c0c

6. Photo by the author, Kathleen J. Hartman, 2016. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

7. See Hartman, Kathleen J. “Chapter 8, Development of Symbolic Art: Mausoleum of Galla Placidia.” Humanities: New Meaning from the Ancient World. Colorado Springs, CO: Pikes Peak Community College, 2020. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

8. See Hartman, Kathleen J. “Chapter 7, Relics of Faith.” Humanities: New Meaning from the Ancient World. Colorado Springs, CO: Pikes Peak Community College, 2020. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

9. Public domain on Wikipedia. Accessed at https://www.medieval.eu/wp-content/uploads/exterior-of-San-Vitale-in-Ravenna.jpg

10. Photo courtesy of santagnese.org, Creative Commons License (CC BY-SA 2.0).

11. Public domain at upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/5/53/ Byggnadskonsten%2C_San_Vitale_i_ Ravenna%2C_ Nordisk_ familjebok.png

12. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:EB1911_Rome Plan_of_Church_and_Mausoleum_of_Constanza.jpg

13. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ravenna_Basilica_of_San_Vitale_wideangle.jpg

14. See Hartman, Kathleen J. “Chapter 8, Orthodoxy vs. Heresy: the Orthodox and Arian Baptisteries in Ravenna.” Humanities: New Meaning from the Ancient World. Colorado Springs, CO: Pikes Peak Community College, 2020. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

15. Genesis 2:10-14 identifies these as the Pishon, Gihon, Chidekel (the Tigris), and Phirat (the Euphrates).Other sources declare these to be rivers of honey, milk, wine and oil.

16. Revelation 5:1, KJV: “A book written within and on the backside, sealed with seven seals.”

17. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Apse_mosaic_-_Basilica_of_San_Vitale_(Ravenna).jpg

18. Photo by the author, Kathleen J. Hartman, 2016. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

19. Public domain at upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/d/d6/Basilica_di_San_Vitale_Arc_%28Ravenna%29.jpg

20. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Basilica_of_San_Vitale_-_Lamb_of_God_mosaic.jpg

21. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ravenna,_basilica_di_San_Vitale_(067).jpg

22. The Book of Revelation 5:13 (KJV): “Worthy is the Lamb that was slain to receive power, and riches, and wisdom, and strength, and honour, and glory, and blessing. And every creature, which is in heaven, and on the earth, and under the earth, and such as are in the sea, and all that are in them: heard I saying, Blessing, and honour, and glory, and power be unto him that sitteth on the throne, and unto the Lamb forever and ever.”

23. Photo by the author, Kathleen J. Hartman, 2016. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

24. See Hartman, Kathleen J. “Chapter 8, Hagia Sophia in Transition.” Humanities: New Meaning from the Ancient World. Colorado Springs, CO: Pikes Peak Community College, 2020. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

25. Public domain at www.ancient.eu/uploads/images/4504.jpg?v=1569514700

26. Public domain at www.ancient.eu/uploads/images/4503.jpg?v=1569514700

27. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Basilica.di.san.vitale.ravenna.jpg

28. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ravenna_Basilica_of_San_Vitale_mosaic5.jpg

29. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mosaics_of_Theodora_-_Joy_of_Museums_-_Basilica_of_San_Vitale.jpg

30. Public domain at www.ancient.eu/uploads/images/4504.jpg?v=1569514700

31. See Hartman, Kathleen J. “Chapter 7, Anticipating Byzantine Culture.” Humanities: New Meaning from the Ancient World. Colorado Springs, CO: Pikes Peak Community College, 2020. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

32. See Hartman, Kathleen J. “Chapter 7, The Ambition of Constantine.” Humanities: New Meaning from the Ancient World. Colorado Springs, CO: Pikes Peak Community College, 2020. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

33. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mosaic_of_Justinianus_I_-_Basilica_San_Vitale_(Ravenna).jpg

34. Photo by the author, Kathleen J. Hartman at the Byzantine and Christian Museum, Athens, 2017. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

35. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mosaic_of_Justinianus_I_-_Basilica_San_Vitale_(Ravenna).jpg

36. Public domain at upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/f/f2/Corona_de_%2829049230050%29.jpg

37. Procopius of Caesarea, The Secret History, Chapter VIII. sourcebooks.fordham.edu/bsis/procop-anec.asp

38. Procopius of Caesarea, The Secret History, Chapter X. sourcebooks.fordham.edu/basis/procop-anec.asp

39. Photo at San Vitale by Kristine Betts, 2019. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

40. See Hartman, Kathleen J. “Chapter 8, Witnesses for Idealism: Sant’ Apollinare Nuovo.” Humanities: New Meaning from the Ancient World. Colorado Springs, CO: Pikes Peak Community College, 2020. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

41. Photo by the author, Kathleen J. Hartman, 2016. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

42. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Theodora_mosaic_-_Basilica_San_Vitale_(Ravenna)_v2.jpg

43. Additionally, their peculiar “Persian” costumes are similar to those worn by the followers of Mithras. See Hartman, Kathleen J. “Roman Civilization. Religion During Pax Romana.” Humanities: New Meaning from the Ancient World. Colorado Springs, CO: Pikes Peak Community College, 2020. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.