7.7 Christ as the Good Shepherd

Before the legalization of the faith, early Christians had neither sacred images nor sacred places. Having developed from the Jewish tradition, both graven images and religious architecture were prohibited. As for idols, the prohibition from the Ten Commandments was unequivocal: “Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image, or any likeness of anything” (Exodus 20:4, KJV). Initially, neither was specialized architecture important. The tabernacle was a portable place of worship (a two-room tent) as the people were traveling in the Wilderness. Christians, identifying themselves as the spiritual protégé of the Israelites, were in full agreement about the unimportance of religious structures. According to Acts 17:24: “God that made the world and all things therein…dwelleth not in temples made with hands” (KJV).

Furthermore, early converts to the faith were from the lower and middle class. They did not have the money for the luxury of art. Besides, decorative arts were considered too worldly, and in an even harsher understanding, worldly arts were pagan. They cared little for the culture of their own society; by converting to Christianity they were trying to escape the culture of this “known world.” Their meeting places were not in churches, but in private homes, at grave sites of loved ones, or outdoors.

After persecution ceased upper-class individuals began to be converted to the movement and images became more prevalent. Furthermore it was argued that the prohibition was not absolute since, only five chapters after the commandment that prohibits images (Exodus 20: 4), God gave instructions on how to make three-dimensional representations of the Cherubim for the Ark of the Covenant (Exodus 25:18-20). Used in a didactic manner, Christian art could give instruction and illustrate Christ’s humanity: that he was the image of God the Father.

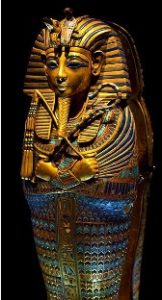

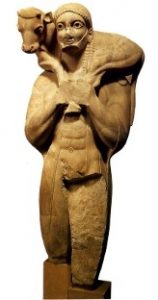

In an act of syncretism, many inoffensive and ambiguous pagan images were appropriated by Christians, to be understood in a specifically Christian way. The image of the Good Shepherd was not an original Christian convention. We have already studied three possible shepherding predecessors. The Amorite leader Hammurabi was known as “the good shepherd who cared for his flock” [image 7.74]. As an intermediary between Shamash (the incorruptible god of truth and justice) and humankind, Hammurabi was the earthly law enforcer, and if offended he could forgive in the name of Shamash. Tutankhamen [image 7.75] can serve as a typical Egyptian pharaoh. With his powerful crook and flail, the pharaoh was known as one who cared for his people. Holding the tools of farming and shepherding, he also represented fertility and rebirth, death and resurrection. You may not have studied the image known as Moschophoros (“calf-bearer”), but likely you recognize the Archaic smile of this kouros [image 7.76]. Moschophoros was perhaps bringing a calf for sacrifice at a temple, or he was protecting the animal from violence.

The care of the Good Shepherd was particularly relevant at the time of death. Both Jews and Christians understood the significance of the shepherd in the light of Psalm 23: “The Lord is my shepherd; I shall not want. He maketh me to lie down in green pastures: he leadeth me beside the still waters” (KJV). Images 7.77 and 7.78 both depict Christ in an Arcadian setting with sheep, birds and trees.

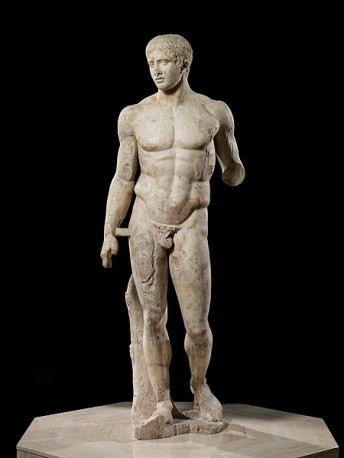

There are significant changes when we compare the “more sophisticated” Christian sculpture of the Good Shepherd [image 7.80]. The shepherd stands with contrapposto weight-shift which is reminiscent of the Classical Greek Doryphorus [image 7.79]. The shepherd’s face is youthful and reminds us of the Hellenistic Apollo Belvedere [image 7.81]. The space is open; he is animated and he turns to be engaged with something unseen by us. Significantly, he is clothed, which would have been especially appreciated by Christians. A specific Biblical reference from John 10:11 was often attached to this depiction: “I am the good shepherd; the good shepherd giveth his life for his sheep” (KJV).

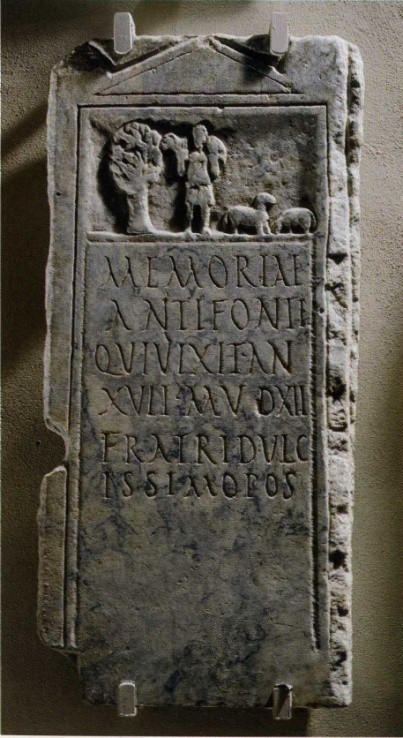

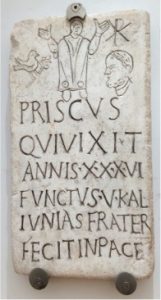

While we’re in Rome, let’s examine two more funerary slabs [images 7.82 and 7.83]. These feature three other popular symbols. Both display the  (Chi-Rho) monogram (aka Cristogram), which the Emperor Constantine had inscribed on the shields of the men fighting the Battle at Milvian Bridge.9 Both depict the deceased standing in the orant position, the Greek position of prayer in which the arms are uplifted in supplication.10 And both have a bird, presumably a dove holding an olive branch of peace. The text on the plaque in image 7.83 commemorates the life of Priscus, who died at age 36. The text closes with the Christian statement “fecit in pace” (“be/rest in peace”).

(Chi-Rho) monogram (aka Cristogram), which the Emperor Constantine had inscribed on the shields of the men fighting the Battle at Milvian Bridge.9 Both depict the deceased standing in the orant position, the Greek position of prayer in which the arms are uplifted in supplication.10 And both have a bird, presumably a dove holding an olive branch of peace. The text on the plaque in image 7.83 commemorates the life of Priscus, who died at age 36. The text closes with the Christian statement “fecit in pace” (“be/rest in peace”).

In Jewish burial practices, the body laid in the tomb for about a year and then the bones were gathered up and redeposited with others from the family or clan in a pit or cavity, a “charnel pile” within the burial chamber. This tradition was a response to the Genesis 49:29 desire “to be gathered with my fathers.” Around Jerusalem, in the first century CE, bones were collected in ossuaries (bone boxes made of soft limestone or chalk, long enough to hold the femur and other large bones).

Roman law forbade burial within the city walls. Burials took place in the necropoli (cities of the dead) which lined the roads leading away from the towns. In the catacombs arcosolia (indented shelves) were cut into the walls of the chamber. The ossuary, which may have been decorated with geometric or floral motifs, was placed on one of these shelves. Romans allowed private group cemeteries, but Christians felt a need for their burial to be distinguished from pagan burials. Quoting Tertullian (Roman theologian and Christian apologist from Carthage, 160-230 CE), “It is permissible to live with the pagans, but not to die with them.”

After Rome had conquered Egypt in the second century CE burial of the intact body became more popular than cremation. As a result, the catacombs became not a necropolis (city of the dead) but a coemeterium (land of sleeping men) [image 7.84]. Cut into the tufa (volcanic ash), the coemeterium could be as many as seven levels deep, each level lined with loculi (rectangular niches for 2-3 bodies) which were closed with tegula (a stone slab sealed with cement hopefully prevented the stink of putrefaction from getting out).

Of course images of the Good Shepherd [images 7.85 and 7.86] continued to be popular. As a funerary memorial, this shepherd offered salvation, not money, or property, or service to the state. The Good Shepherd appealed to a higher power; it denied the value of the Emperor. It was probably just as well that burials were regarded in Roman law as sacrosanct, so that even during periods of persecution Christian tombs were left largely unscathed, attracting little notice from Roman authorities.

When this course visited Rome we admired mosaics on the floors and frescoes on the ceilings of Roman homes.

This fresco [image 7.87], on the ceiling of a luxury villa house in the harbor city of Ostia, is particularly impressive. The spoked-wheel design, with a center oculus, resembles a personal Pantheon. The house dates from the early 3rd century CE and was probably enjoyed as a summer retreat from the heat of the city. In my imagination I can hear one of his slaves exclaiming, “My master has the most fabulous design painted on the ceiling of his house! We could do a similar design, celebrating the Good Shepherd and the stories he told.”

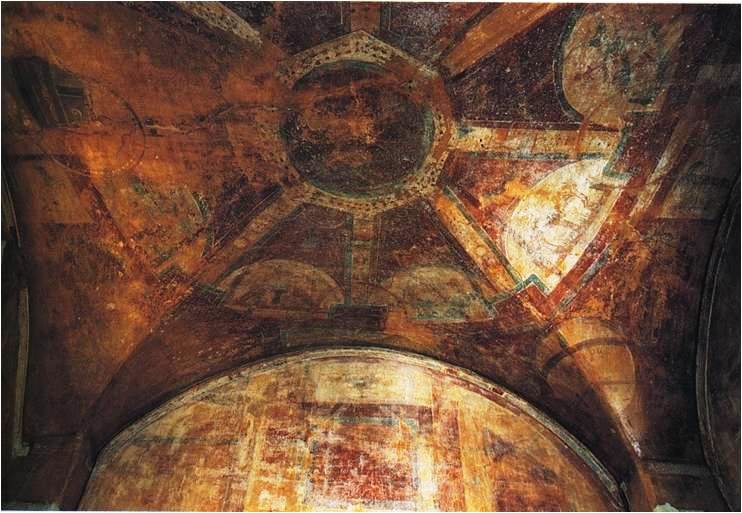

Today we identify the Roman catacomb in image 7.88 as the Catacomb of Sts. Peter and Marcellinus. The spoked- wheel design of the vault mural is in the cubicula, a small room off the long gallery in which families and small groups might gather. Sarcophagi were placed around the room. Crowning the dome of heaven is Christ as the Good Shepherd. He is surrounded by sheep and holds a lamp over his shoulder. Another symbol which was gaining in popularity was the cross, which here reaches out in four directions toward the semicircles in which are depicted the story of Jonah. Chapters 1 and 2 in the Book of Jonah told the story of God causing Jonah to be thrown overboard in a storm, swallowed by a whale and later released, repentant and unscathed after three days in the “belly of the whale.” In the semicircle on the left, Jonah is being cast from his ship. In the right semicircle, he emerges from the whale. In the lower semicircle he is safe on dry land and reclining on a gourd vine in paradise. Matthew 12:39-40 relates the interpretation of this story as a parable about Jesus’ death and resurrection. The intermediate figures have their arms raised in the orant position of prayer.

The orant prayer position was a development from the Greek posture of prayer. In Christian art the outstretched arms became a symbol of the faithful dead. In the a fifth century Greek chapel north of Rome, known as the Catacombs of Priscilla, is a lunette known as the Crypt of the Veiled Lady. Flanking the Veiled Lady on the left is an image of a teacher/philosopher with his pupils. On the right a woman holds a child on her lap. In the center is the figure we call Donna Velata, the “veiled lady” [image 7.89]. But is the figure male or female? It is not recognizable. Even the setting gives no clues about the figure’s identity. All we really know about Donna Velata is to be witnessed in the deep-set eyes which anticipate the Byzantine icon, and that he or she stands in the orant position, the Greek position of prayer.19

A MUSICAL REACTION TO THE CATACOMBS

If you can, picture yourself standing beside a deceased loved one, with your family members, inside the catacombs, five, or six or even seven levels beneath the ground. You would probably be quick to remark that it is dark in here, and humid, and smelly, and mysterious. What could you place on the ledge of that nearby niche that would overcome the darkness and dampness? Candles. How to combat the smell? Flowers and incense. And the mystery? Sing, sing the comforting words of the Psalms.

Greek music was born amidst the patter of dancer’s feet, on an open stage in showers of sunlight. Christian music was born in subterraneous vaults. Psalms were muttered and mumbled, around corners and down corridors, by untrained voices, rather than sung. They did not use long-drawn out notes, as practiced singers would have done, but heartfelt lingering over their loved words, with sighs of earnest emotion.

Catacomb burials were abandoned in the fifth century. With the tradition forgotten, the catacombs were granted better preservation than above-ground cemeteries. But they were still respected as sacred space, and with the legalization of Christianity funerary basilicas were built directly above or adjacent to the cemetery (i.e. St. Peter’s Basilica and St. Paul’s Outside the Walls, both in Rome). Or the relics were moved to the city and reburied under altars or in crypts of the newly consecrated churches (Sant’ Apollinare Nuovo in Ravenna). And in today’s modern church, is not a communion table about the same dimensions as a sarcophagus? And are not flowers and candles placed on that table? And what is incense if not a mystery? It is first a solid, and then, poof, it is a nothing.

While we have specimens and theories about early music, we know very little about the actual music. Secular music was usually improvised. Performers had neither the knowledge required to commit their inspiration to paper, nor any desire to make their creation available to possible rivals. We do know about the beginnings of sacred music, because music had a utilitarian function: to assist the worshipers to pray together.

The Greeks and the Romans displayed their gods in statuary and paintings. But the one God of the Hebrews commanded that He remain invisible, that no graven images limit the omnipresence of God. So, Jews honored God with forms that were outside the ordinary interchange between humans: music and poetry.

The Book of Psalms had legitimized the use of music in acts of worship. Timbrels, strings, pipes and cymbals are mentioned, and dance could be used to glorify God. But dance? That reminded Christians of the sensualities of pagan rituals. The strong patterned beat suggested the obscenities of the stage and could, indeed, be the devil’s playground. Neither would Christians sanction any images of naked divinities; nude athletics as well as public bathing were also forbidden. Christians would later develop an emphasis on chastity and celibacy.

And instruments? They, too, will be considered dangerous. The thirteenth-century theologian Thomas of Aquinas presented a clear argument for “a cappella” (“only vocal”) music: “The bodily shape of an instrument keeps the mind too busy, introducing a carnal pleasure.”20

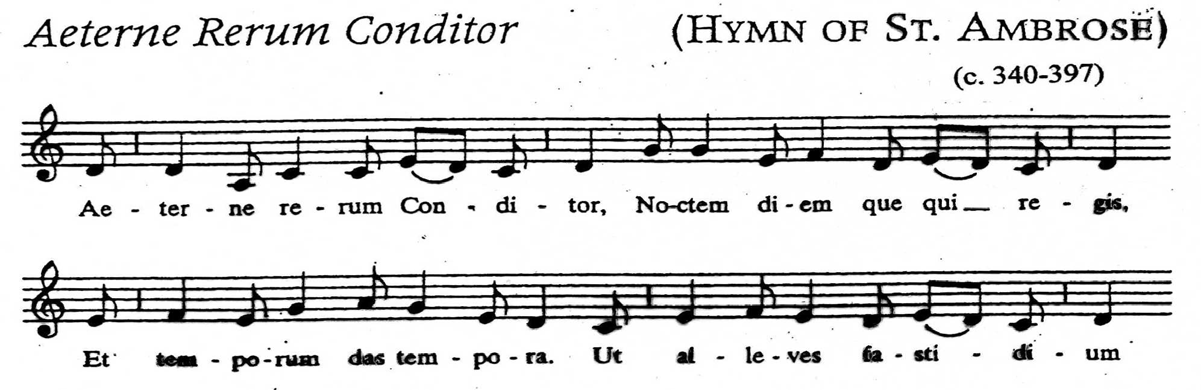

Suggested related music from this time includes the Ambrosian Chant “Aeterne Rerum Conditor.”

In Latin this music is known as “musica plana” or “cantus planus.” In English it is known as Plainchant or Plainsong. It is based upon Byzantine (i.e. Greek/Pythagorean) modes of music and is similar to the music of Jewish worship. The music is simple, serene and balanced, with a feeling of poignant ethos. Plainchant is also known as an “Ambrosian” chant (a title which does not refer to its sugary sweetness), in tribute to St. Ambrose (340-d. Trier, 397) who was the bishop of Milan when Christianity was becoming the religion of the Roman Empire. It was Ambrose who instructed and baptized Saint Augustine. St. Augustine is credited with the statement, famous to choristers, “One who sings once prays twice.”

Significant elements:

Melody line is simple. A single line proceeds stepwise, rising and falling with the words. The melody is also strophic: each line (or stanza) is sung to the same music.

Rhythm (syllabic). Each syllable is a single note. The words from the Latin Bible are easy to sing.

A contemporary example of syllabic rhythm, in English, is “My Country ‘tis of Thee.” The words are set to a triple rhythm of iambic tetrameter (short-long, etc.). By emphasizing three-ness, Ambrose was battling Arian heresy. His goal was to use congregational performance as a weapon against heresy.

Of no creative importance: Harmony (monophony), Pitch, Meter, Tempo, Dynamics, Instruments

Try reciting a translation of this hymn in iambic tetrameter.

Iambic (from Greek metrical foot: one short syllable followed by one long syllable)

Tetrameter (from Greek “four meter:” repeat the “foot” four times) short-long, short-long, short-long, short-long

To count the hymn in 3s (as Ambrose would have emphasized), the pickup starts on “3” and the emphasized syllable starts on “1.” Count it out. Surprisingly, it works!

O Splendor of God’s glory bright,

3 1 2 3 1 2 3 1 2 3 1

O Thou who bringest light from light, O Light of light, light’s living spring, O Day, all days illumining!

Gregorian Chant will not develop until 590-604 under Pope Gregory the Great.

References:

1. Public domain at www.ancient.eu/image/541/hammurabi-and-shamash/

2. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Canopic_Coffinette_(Tutankhamun).jpg

3. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:ACMA_Moschophoros.jpg

4. Photo by the author, Kathleen J. Hartman, 2017. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

5. Photo by the author, Kathleen J. Hartman at the Epigraphic Museum at the Museo Nazionale Romano, Baths of Diocletian, Rome, Italy, 2017. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

6. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Doryphoros_MIA_866.jpg

7. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Belvedere_Apollo_Pio-Clementino_Inv1015.jpg

8. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Marble_statue_of_The_Good_Shepherd_from_the_Catacombs_of_Domitilla_full,_Vatican_Museums.j pg

9. See Hartman, Kathleen J. “Constantine: Chapter 7, The Ambition of Constantine.” Humanities: New Meaning from the Ancient World. Colorado Springs, CO: Pikes Peak Community College, 2020. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

10. See Hartman, Kathleen J. “Chapter 7, Anticipating Byzantine Culture.” Humanities: New Meaning from the Ancient World. Colorado Springs, CO: Pikes Peak Community College, 2020. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

11. Photo by the author, Kathleen J. Hartman at the Epigraphic Museum at the Museo Nazionale Romano, Baths of Diocletian, Rome, Italy, 2017. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

12. Photo by the author, Kathleen J. Hartman, at Museo Nazionale Romano, Baths of Diocletian, Rome, Italy, 2017. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

13. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Roma,_Catacombe_di_San_Sebastiano_(1).jpg

14. Public domain at www.ancient.eu/image/10352/the-good-shepherd-catacombs-of-priscilla/

15. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Good_shepherd_02b.jpg

16. Cited brewminate.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Ostia39.jpg on Wikimedia Commons

17. Good Shepherd, Orants, and the Story of Jonah; cruciform vault mural from the Catacomb of SS. Pietro e Marcellino, Rome. 4th century. www.courses.psu.edu/art_h/art_h111_bel101/images/out4/shepherd.jpg

18. Public domain at www.ancient.eu/image/10353/the-cubiculum-of-the-veiled-woman/

19. See Hartman, Kathleen J. “Constantine: Converting the Empire to Christianity. Anticipating Byzantine Culture.” Humanities: New Meaning from the Ancient World. Colorado Springs, CO: Pikes Peak Community College, 2020. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

20. Thomas of Aquinas, Summa Theologica, “Against Musical Instruments.”