7.6 CONSTANTINE’S GREAT DECISIONS

Constantine would have loved his enhanced title: “Constantine the Great.” He probably received the honorific designation “The Great” from Christian historians long after he had died, but we may be assured he would have felt complimented to be in the company of the Persian Cyrus II the Great, the Greek Alexander the Great, and the Roman general Pompey the Great.

As students of Humanities, we can make use of “The Great” title to recall Constantine’s two great decisions, both of which have changed the world. His first important imperial decision was to give Christianity the legal status of “most favored religion.” Related to this determination, and in recognition that debts must be paid to powerful gods, Constantine sanctioned the building of the first overtly Christian churches in Rome, Jerusalem and Constantinople. The second great decision was to move the capital of the empire from Rome to a new Rome, known after his death as Constantinople. All factors considered, Constantine clearly took full advantage of his “great” Imperial Authority.

As discussed in the Byzantine Era chapter “The Ambition of Constantine,” the fourth century was a pivotal century in the history of Christianity.1 In the early 300s Christianity had been a persecuted religion, practiced by a small minority.

Under Constantine’s legalization in 313, the status of “most favored religion” gave Christians preferences unmatched by other citizens. Christians enjoyed job bias: no more pagans (or even those who had recently abjured pagan beliefs) would be appointed as magistrates, prefects or provincial governors. Christians received fiscal privileges (including religious tax exemption). They were excused from the duty of sacrifice, as Jews had been ever since the reign of Caesar Augustus.

Christians celebrated state-recognized holy days. Their properties, which had been confiscated during Diocletian persecution, were restored and they received sanctioned permission to build churches. As the century progressed Christianity became the official religion of the Roman Empire under the rule of Theodosius I (392-395). In colloquial jargon, over the course of the century Christianity had gone from “we’ll give you to the lions” to “we’ll give you a job.” The Christian church, now linked with state power, would never be the same.

Constantine’s second great decision was clearly an attempt to reunify the Eastern and Western parts of the nation. In 330 he relocated the capital of the empire to a new and great Christian city where he and later Christian emperors could hold court in an environment not contaminated by physical memories of paganism. While Rome had become infamous for scenes of plot and counterplot, treason and conspiracy, in this new Rome there were no temples to pagan gods and no relics of pre-Christian institutions. In his review of possible locations Constantine had considered Naissus (his birthplace),

The move of the capital inaugurated the era frequently referred to as “medieval.” Medius simply means “middle,” and aevum means “age.” The Medieval Era was not the “mid-evil” age of darkness and barbarism that twenty-first century gremlins would have us imagine. The era was named by Renaissance scholars who considered everything that happened between the end of the Roman Empire and their own age as “middling,” i.e. unimportant, of little value. As moderns, we have inherited several fundamental aspects of government from early Medieval sources, including an imperial court with diplomatic service, a civilian bureaucracy, the ceremony of coronation and the female exercise of political power.

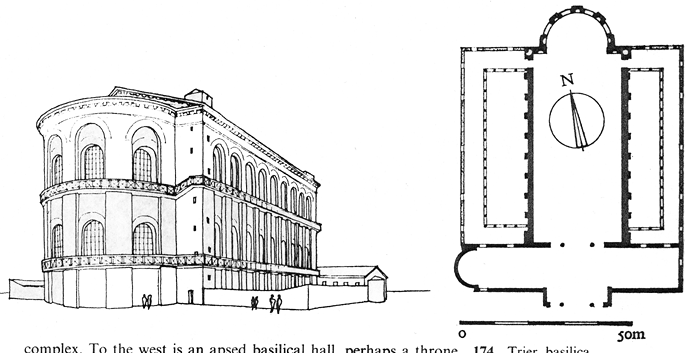

In recognition of the significance of the 312 Battle of Milvian Bridge as a turning point that had permitted him to become Emperor of Rome, Constantine acknowledged that he owed a debt to the Christian God. As soon as he had consolidated imperial power he began a vast building program with the construction of the first overtly Christian churches in Rome and the Holy Land, most of which were built on the basilica plan. The design was similar to his own audience hall in Trier known as the sedes imperialis (Imperial seat) of the northern German territories [image 7.55]. The Aula Palatina (palace hall) was strictly a secular building used for various public functions (audience hall, reception hall, law court). It was not used for worship and did not actually become a church until 1856 when King Friedrich Wilhelm IV of Prussia had the hall rebuilt and converted from a civic building into a church—but the basilica styled Throne Room was a precursor to and prototype for the earliest Christian churches.

Perhaps the basilica is still standing, some 1700 years after construction, because the exterior walls of the Aula Palatina are 2.7 meters thick, with even wider foundations. Actually, only the exterior walls of the building survived the bombing of World War II. It is said that as fire that engulfed the building the organ pipes (mounted at the west end) cried a truly mournful hymn. While the exterior appears to be just plain red brick from a distance, we can observe that it originally had painted plaster/stucco, with yellow flowers painted around the windows [image 7.56].

The floor plan [image 7.57] gives an indication of how the exterior relates to the interior. We should remember that a cloister and the palace (palatina) originally surrounded the building.

Roman grandeur was certainly in play here: the exterior measures 221‘ long and 109’ high. The relationship of the interior depth to the interior height was expressed in carefully thought-out Pythagorean (Greek) proportions of 2:1. The interior is a double square of 100 x 200 Roman feet.

Several features of the Aula Palatina were typical of the basilica style; others were enhanced at this location for the benefit of the ruling Caesar:

- The single entrance at the end of the building emphasized the building’s length. The 221’ long audience hall at Trier is the longest room surviving from antiquity.

- Clerestory windows provided interior light. This giant hall appeared to have been formed out of light, which would have suggested the power of the Roman Empire and its Imperial sovereign. At Trier the windows in the rounded apse become smaller toward the middle, also making the room seem longer. Each thin glass pane8 measures 50 x 65 cm. The Basilica of Old St. Peter’s in Rome, because it was financed by Constantine, may have also had glass in its windows, or there may have been stone slabs filled with thinner translucent stone, or the windows may have been left open.

- Interior decoration was certainly not a requirement, but there was plenty of available wall space for frescoes or mosaics and many churches, not much newer than this, will be decorated. At Aula Palatina you must use your imagination to visualize how the light originally reflected on golden mosaics, painted stucco, sculpted busts and the multi-colored marbles lining the floor and walls: white from Carrara, black from Belgium, yellow from Tunisia, green from Greece and purple porphyry from Egypt. Scars left from the removal of those marble panels may still be seen, especially on the west wall, in image 7.5.8 The floor was black and white.

- A flat wooden-truss ceiling. The ceiling of the Throne Room had an additional optical illusion to make the already large room appear even more intimidating: the flat ceiling was coffered (recessed, like stepped pyramids or ziggurats) to make the room appear higher.

- A huge interior space, without internal supports. This allowed for stately processions toward the designated focal point, the apse.9 During an audience, according to the church father Athanasius, the Emperor sat in the apse under the triumphal arch and behind a curtain which stretched in front of the throne. Established in divine majesty upon the Seat of Justice (sedes iustitiae) on the bema (throne on the raised area) [image 7.59], with his feet on a footstool, the Imperial ruler received homage, and as law incarnate, he dispensed justice. The story is told that after a petitioner’s name had been announced, the subject was allowed to approach the throne, and prostrate10 himself. He had to be accompanied by a person of good reputation; if an assassination were attempted, the guarantor was to be quickly executed. Upon leaving, the petitioner was not permitted to turn his back on the sovereign; he had to shuffle backwards, seemingly endlessly, out of the room.

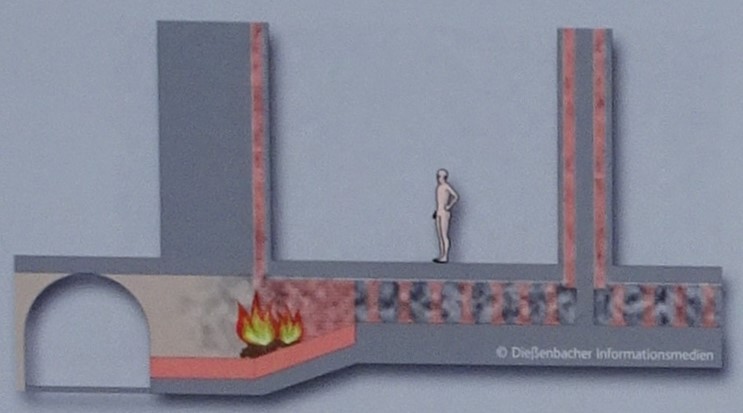

Only the apse of the Aula Palatina was heated. For the benefit of the Imperial ruler, or representative, a hypocaust system (similar to that in the Roman baths) was installed under the floor [images 7.60 and 7.61].

While the Aula Palatina was not built as a church, the basilica, as a prototype, had several advantages:

- It was not associated with any pagan cults.

- Every proper Roman town had an administrative basilica, so examples of the building style were plentiful.

- It was relatively quick and easy to build, unlike central plan domed and vaulted elevations.

- It could be readily adapted to the materials and resources locally available as well as to the anticipated size of the congregation.

- The focus was clearly inward: impressive, dignified, and Roman [image 7.58].

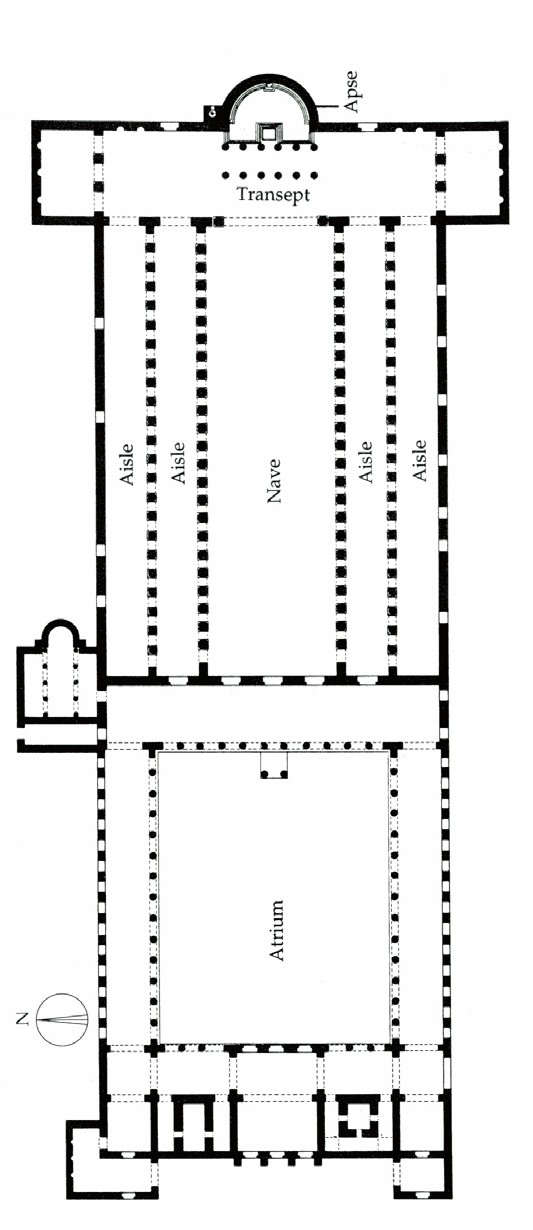

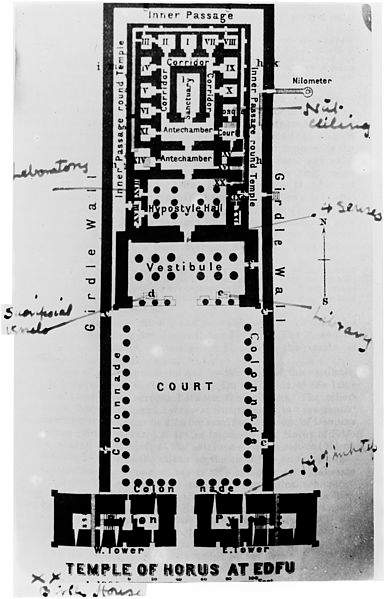

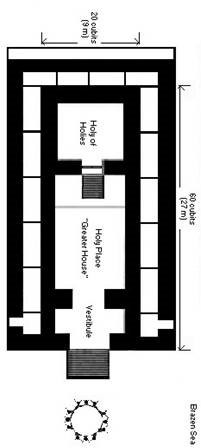

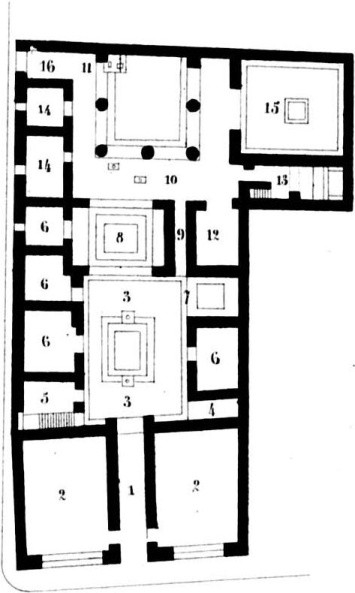

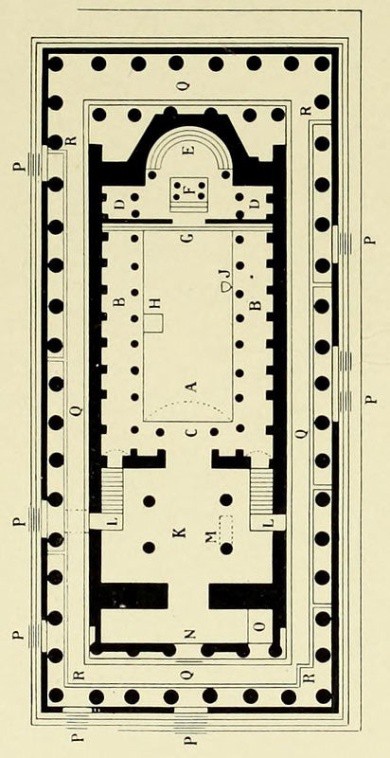

The basilica plan, with a straight central axis directed toward the East [image 7.62], was easily adapted from recognized building plans [images 7.63-7.66] and then enhanced with new meaning.15 Three general zones may be identified. The courtyard, portico or atrium came to represent this earthly world; it became known as the narthex. The main hall came to represent the Kingdom of God; it became known as the nave. The Holy of Holies came to represent heaven; it became known as the sanctuary.16

As one approached the narthex on the west end of the church between the atrium and the nave one felt the stimulation of transition. In the atrium people might talk excitedly with their friends. Some individuals strolled in the quadrarectangular ambulatory (covered walkway) around the perimeter. In the atrium one could see the impluvium (in a Roman house, the impluvium was the central trough for rainwater) which had become the baptistery (for ritual washing). In an action similar to passing through the Propyleaum on the Acropolis in Athens, the narthex provided a clear separation between the temporal and spiritual worlds.

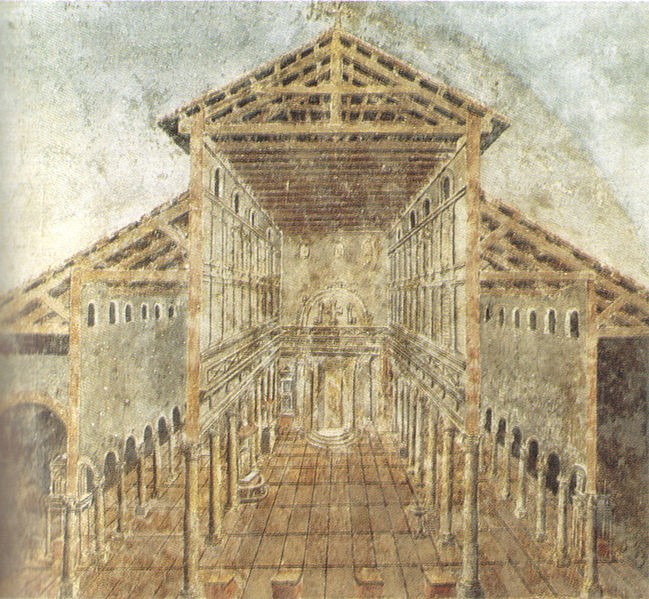

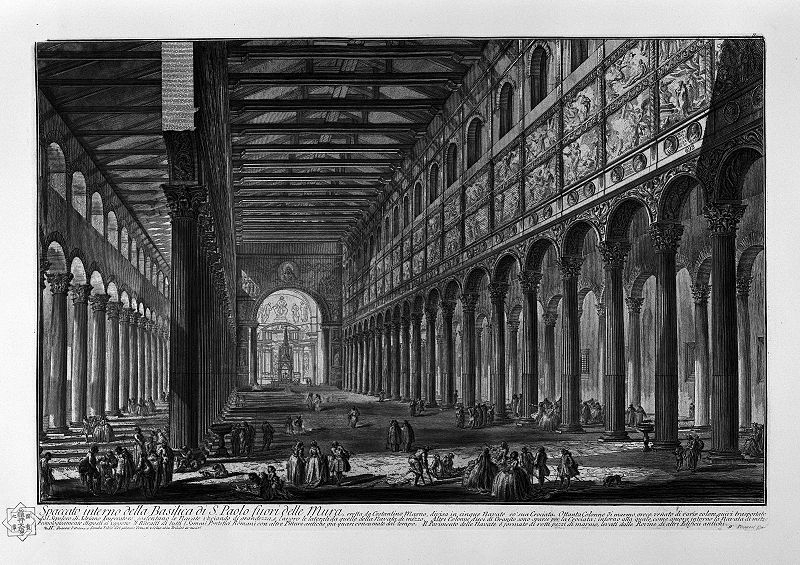

It is our privilege to do things the ancients never could do. In the above image we can stand in the narthex and look into the body of the church, the nave, through all five doors simultaneously [image7.67]. The basilica known as Old St. Peter’s was built for a large congregation, some 14,000 standing individuals. Complimenting the single entrance on the end of the building, the five extended aisles emphasized longitudinal space. The advancing rhythm of the colonnade suggested St. Augustine’s dictum that humans should “progress from blindness to understanding.” Just as the petitioner did before Constantine’s throne, after processing down the aisle toward the altar, the supplicant was required to prostrate him- or herself before the throne. He/she would then recess back out of the church, though it is not known if the penitent had to shuffle backwards as had been necessary in the recession from the throne of Emperor Constantine. Procession, prostration, recession—all were necessary protocols.

The body of the basilica was the nave, a word derived from the Latin word for “ship.” From navis we get the words “naval” meaning “ships,” ”navigate” “to set sail,” and “navel “ meaning “hub.” Like Noah’s ark, the nave suggested a place of refuge from the chaos of churning waters, and salvation within the body of Christ.

A fourth century prayer by St. Augustine is an illustrative exemplar of the significance of the nave:

Blessed are all thy saints who have traveled over the tempestuous sea of mortality and have at last made the desired port of peace and felicity. Oh, cast a gracious eye upon us who are still on our dangerous voyage. Remember and succor us in our distress, and think upon them that lie exposed to the rough storms of troubles and temptations. Grant O Lord, that we may bring our vessel safe to shore, unto our desired haven.xxiii

The transept is a distinctive Christian element which was added between the nave and the sanctuary. Projecting out at right angles from the nave, these “arms,” not coincidentally, reminded the worshipper of Christ’s arms on the cross. Practically speaking, the transept was an area in which dignitaries may be present in the church without “contamination” from plebian folk. In some churches, the elite had a separate entrance into the church through the transept.

The area which had been the Holy of Holies in the Jewish temple continued to hold the liturgical focus. The sanctuary (area surrounding the altar) marked the area separating the celebrant (priest) from the communicant (worshipper). The space was identified by a triumphal arch, now signifying the victorious entry of Christ into Jerusalem and the Christian’s entry into heaven. The focal point was the apse, and in some future Romanesque churches the apse will be tilted, reminding parishioners of Christ’s leaning head on the cross. The most significant addition to the sanctuary, and the central focus for the liturgy, was the bema, a raised platform upon which was placed a wood or stone altar for the celebration of the Eucharist. Additionally, men could read scripture and preach from this platform.

One can easily see the basilica plan in Rome at the old St. Peter’s Basilica (aka St. Peter’s in the Vatican) and at the basilica of St. Paul’s Outside the Walls.

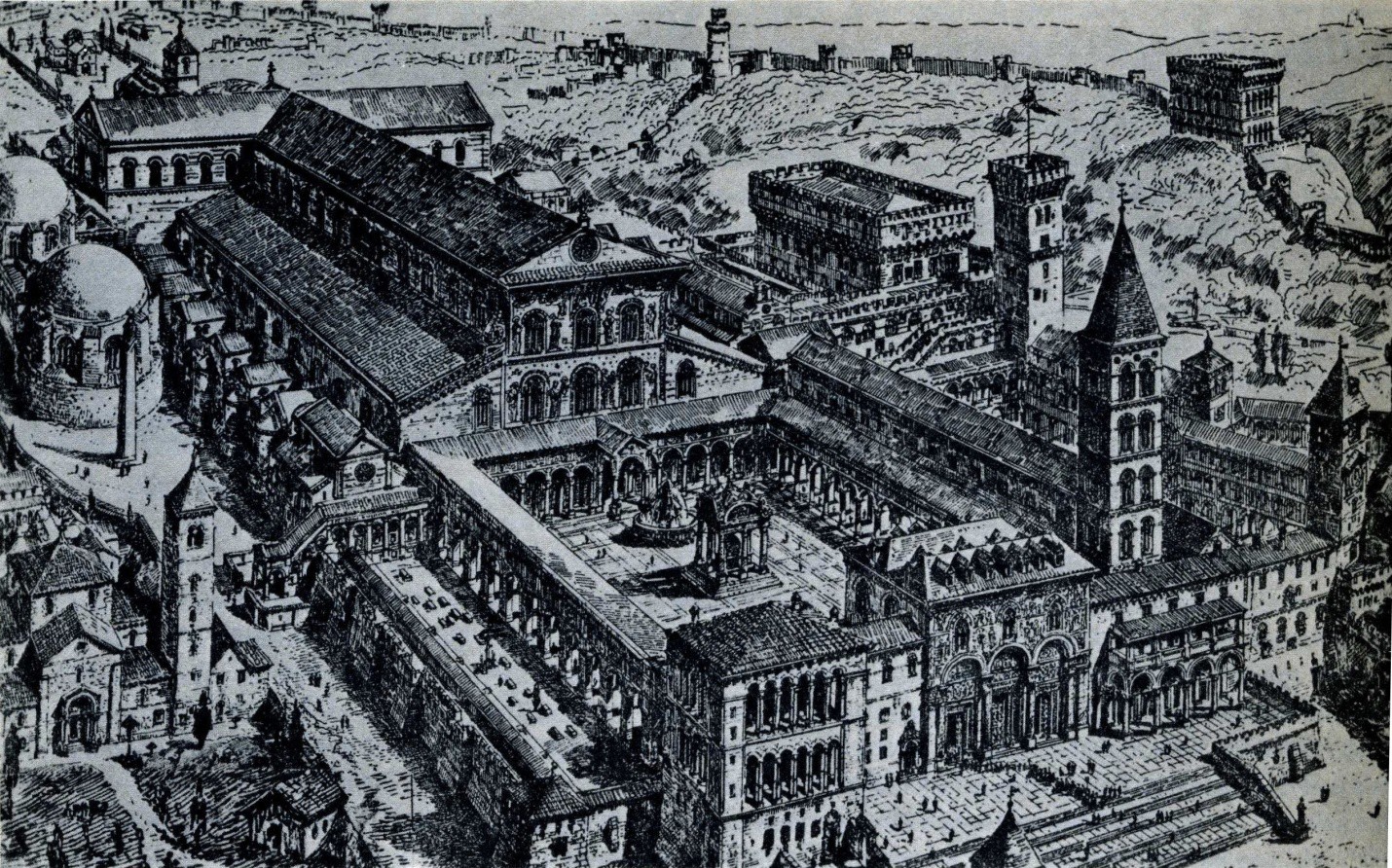

Unfortunately for us, the original St. Peter’s basilica was demolished in stages between 1505 and 1613 to make way for a new structure. After all, by the early sixteenth century the building was 1200 years old and badly in need of renovation and enlargement. Additionally, Renaissance artists Donato Bramante, Antonio da Sangallo, Raphael and Fra Giocondo, Michelangelo, Giacomo della Porta, Carlo Maderno and Gian Lorenzo Bernini needed an outlet for their creative talents. We call this [image 7.68] “Old St. Peter’s” because it was completely replaced by the new building. During our visit to Constantine’s basilica we will be dependent on diagrams and etchings.

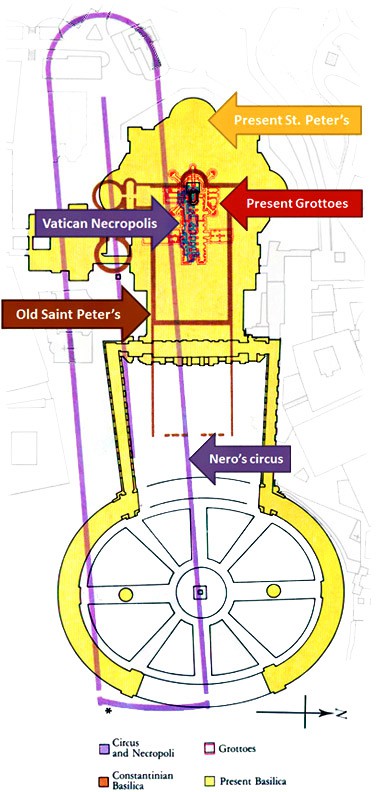

The name for the administrative center of the papacy, the Vatican, was derived from Vaticinor, the Etruscan word for a “hill of foretelling or prophesy.” That certainly suggests that this hill is an auspicious location, and indeed, it has several overlapping layers of history [image 7.69]. Constantine’s basilica was built over the leveled Temple of Cybele, which was the traditional site of Saint Peter’s martyrdom in 67 CE. St. Peter would have been buried in the necropolis, which is identified in the very center as the Vatican Necropolis. The Circus of Gaius and Nero, where Nero put Christians to death in the spectacular persecution that followed the fires of 64 CE, has the appearance of a racetrack. It is outlined in purple. The brown rectangular form marks the Basilica of Constantine, begun between 320 and 327 (and finished about 30 years later), which was intentionally aligned with the four cardinal points. The yellow Greek cross and keyhole shaped courtyard identifies the location of the current basilica, which is still over the tomb of St. Peter.

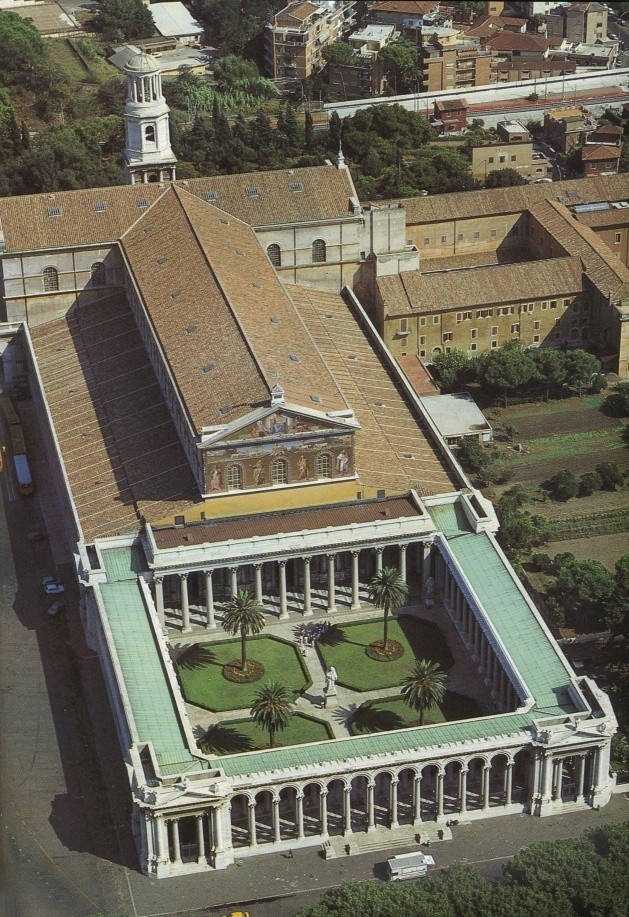

The basilica of St. Paul’s Outside the Walls was, as the name implies, built over the tomb of the Apostle Paul outside the old city walls of Rome [Images 7.70-7.73]. About two kilometers from the Aurelian walls, it is a very walkable distance from the heart of city. The church was founded by Constantine in 324. Though damaged by fire in 1823, it was renovated to the original plans, which had been drawn in imitation of St. Peter’s Basilica.

When one compares Piranesi’s 1750-1758 etching (made 73 years before the fire) [image 7.71] to the rebuilt basilica [image 7.72], the essential conventions of a basilica church may be readily identified. The replacement translucent alabaster windows [image 7.73] certainly added a finishing flourish to the entire project.

A MUSICAL REACTION TO THE “GREAT” DECISION

In future essays we will be studying music from the time of Constantine and the establishment of Christian communities. At this moment, however, the contemporary dance tune Istanbul, not Constantinople is not inappropriate. It’s a bit corny, but it fits the theme, and is a fun connection of Constantinople and Istanbul.

Though popularized by They Might Be Giants, this version by the Trevor Horn Orchestra (recorded for the movie Mona Lisa Smile), is without a cartoon accompaniment so it is easier to be attentive to the elements of music.

All elements of music may be examined, but the driving 2/4 meter is especially significant. The rapidly recurring downbeat drives the dance because there is no time for the heart to rest. Even “One Way” Constantine would have appreciated the “push” of this music.

References:

1. See Hartman, Kathleen J. “Chapter 7, The Ambition of Constantine.” Humanities: New Meaning from the Ancient World. Colorado Springs, CO: Pikes Peak Community College, 2020. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

2. Byzantium had been named in 667 BCE for the Greek colonizer Byzas. The inhabitants and rulers of this Empire did not call themselves Byzantines, but rather referred to themselves as Romans. Their empire, after all, was a continuation of the Roman state. Modern historians call it the Byzantine Empire in order to distinguish it from the Roman Empire that dominated the Mediterranean world from the first through fifth centuries.

3. After 1453 Constantinople was known as Istanbul (the city of the Turks). Appropriately, it is in modern-day Turkey.

4. By Eric Gaba (Sting – fr:Sting) – Own work;For the source of data and the modern name of the cities, see the discussion page, CC BY-SA 2.5. On public domain at https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=856541

5. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Trier_-_Aula_Palatina.JPG

6. Photo by the author, Kathleen J. Hartman, 2018. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

7. http://projects.mcah.columbia.edu/medieval-architecture/htm/related/ma_trier_02.htm

8. According to Pfarrer Guido Hepke, Vorsitzender des Kirchenvorstandes, in a letter dated to this author on August 07, 2018, archaeologists found shards of the original glass in the rubble from the destruction in World War II. Replacement windows were handmade in the late third century “Romain” technique.

9. Be careful with your pronunciation here. The Egyptian asp was a cobra, which was a symbol of divinity. The bite of the asp caused Cleopatra’s suicide. A Texas asp is stinging caterpillar. We want neither of these here!

10. It had also been necessary to prostrate oneself when approaching Alexander the Great.

11. Photo by Hannah Swithinbank CC BY-NC-SA 2.0) by public domain on www.khanacademy.org/humanities/ap-art-history/early-europe- and-colonial-americas/medieval-europe-islamic-world/a/santa-sabina.

12. Photo by the author, Kathleen J. Hartman, 2018. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

13. Photo by the author, Kathleen J. Hartman, in Trier, 2018. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

14. Photo by the author, Kathleen J. Hartman, 2018. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

15. If topographic circumstances prohibited an east-facing axis, the altar would still point to the “Liturgical East.”

16. In post-Reformation congregations, the entire church interior is called the sanctuary.

17. Public domain at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Alfarano_map.jpg

18. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Plan_of_the_Temple_of_Horus_at_Edfu,_Egypt_Wellcome_M0002875.jpg

19. Public domain at https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/3/35/SolomonsTemple.png

20. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pompeii_Region_VI_Insula_8_House_3_plan_01.jpg

21. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Parthenon_byzantine_church,_Adolf_Michaelis_(1835-1910).jpg

22. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Affresco_ dell%27aspetto_antico_della_ basilica_costantiniana_ di_san _pietro_nel_IV_secolo.jpg

23. Potts, J. Manning. Prayers of the Early Church. Nashville: The Upper Room, 1953.

24. Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker, “Saint Peter’s Basilica,” in Smarthistory, August 9, 2015, accessed September 24, 2019, smarthistory.org/st-peters-basilica.

25. Cited from Microsoft Online Images by jfridgley.com/neros-stadia/

26. Photo by Archivio Plurigraf. Published in the Basilica of Saint Paul Outside the Wall. Rome, Pontifical Administration of the Patriarchal Basilica of Saint Paul, 2003.

27. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Piranesi-16012.jpg

28. Photo by the author, Kathleen J. Hartman, 2006. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

29. Ibid.