7.4 Brotherly Love in Turbulent Times

Imagine yourself as a soldier in the Roman Legion. You’ve been serving in the oldest city in The Netherlands, Nijmegen [image 7.8]. The date is year 15 of Trajan’s Reign (113 CE). Trajan has been expanding the empire of 50 million people to its greatest extent, 3.5 million square miles. Being an effective Roman general, Trajan’s great military victories have been commemorated with classically influenced columns and inscriptions, sculptures and triumphal arches [image 7.9]. Proper towns have been built with paved streets, water supply and a forum with its administrative basilica, markets and temples. Additionally, every settlement has commoda (people’s palaces): stadia, circuses, public baths and amphitheaters.

As a member of the Legion you have been paid a basic wage of three solidi a year [image 7.10]. It was from this coin that future legionnaires will be known as “soldiers.” (The German language turned the word solidus into skelding, the origin of shilling.)

Upon finishing your service you received a copy of your military record [both halves, images 7.11 and 7.12]. This small folding bronze double tablet, your diploma, authorized your rights of Roman citizenship.

By studying the map, the coins and the diploma (all from the Museum Het Valkhof, Nijmegen, The Netherlands) we can deduce several characteristics of Roman civilization: trade, roads, citizenship, a single code of laws, a unified currency, soldiers and enforced peace of (at the time of Trajan) 400,000 men. Pax Romana was marvelous for spreading the Roman values of Authoritarianism, Organization and Utilitarianism. Though the “peace” was without the political freedom as the Greeks had understood it and more limited than had been experienced in Republican Rome, it was a more continuous peace than the Mediterranean had ever known. However, like an autostrada which goes in two directions, that ordered civilization also had “oncoming” traffic. Lured by relative stability and security, cultivated land and wide borders, barbarian gladiators, slaves and freed-men poured into the army and then into Roman society.

The ordered civilization of Pax Romana ended with one long period of civil wars, usurpations and violent transfers of power. Between 235 and 260 CE more than 20 emperors took the throne, and all but one died violently, either in battle against Roman enemies or through assassination or lynching. The myth of the so-called divine emperor [image 7.13] has been cancelled out. Goodbye, also, Humanism and Individualism. For the foreseeable future, Authoritarianism will be a significant value.

The time of Roman power and grandeur had passed. With the crumbling of Rome the empire was plunged into military anarchy. In an effort to control the far-flung empire, power was given to local leaders. The imperially sanctioned bureaucrats raised taxes, doubled the size of the army and devalued the currency, but the economy continued to spiral downward with deeper and deeper hyperinflation. Without money, and having lost their confident can-do Roman spirit, public building stopped almost completely. Urban centers were depopulated as inhabitants fled to the countryside for safety. Taking up the roads, citizens built city walls. Thus it was that hill towns in Italy and Spain would develop different accents, dialects, breads, sweets, pasta shapes, histories and myths.

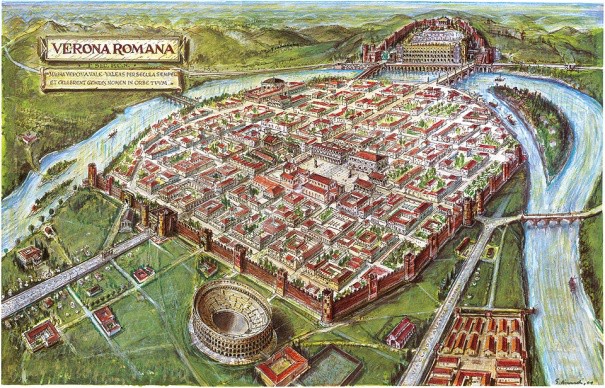

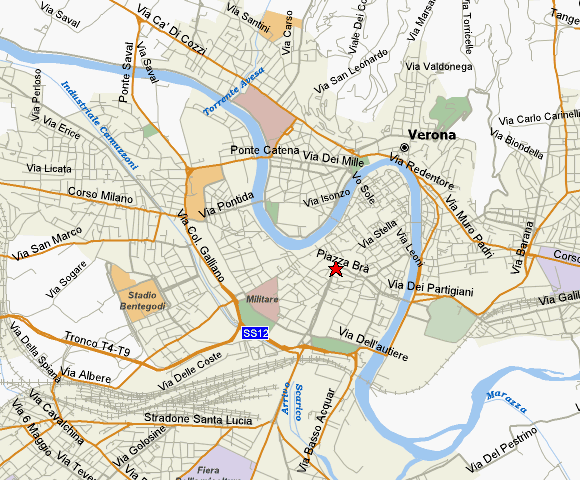

These reused paving stones may still be seen in modern Verona, Italy. The protective city walls are evident in the reconstructed vision of the old fortification of Città Antica between the Adige River and the Via Dei Partigiani [image 7.14]. Modern-day roads [image 7.15] were shaped by that fortification, with an occasional need to cut through those walls. We can still see the stacked paving stones from which those defensive walls had been built [image 7.16].

Seeking to bring some stability to the far-flung Empire, openly autocratic Diocletian (r. 284-305) expanded upon a notion of joint rule which had been tried earlier in Republican Rome.9 In 293 Diocletian ripped away all remaining façades of republicanism with the creation of a Tetrarchy, a rule-of-four. By dividing the empire in half he created the Western Roman Empire and the Eastern Roman Empire (also to be known as the Byzantine Empire). These two divisions were further subdivided into four quadrants [image 7.17]. The four new dominions were smaller and more manageable. The Augustus (emperor) Diocletian maintained his rule of the eastern quarter (from Nicomedia in Bithynia, Thrace, Asia, and Egypt). Conveniently for him, this area had greater economic and demographic resources and was inaccessible to those pesky Germanic barbarians. His Caesar (“chosen successor”), Galerius (ruling from Thessalonike), was responsible for the Danube frontier and the Balkans. In the west Diocletian elevated one of his officers, Maximian, to an equal position of co- emperor. Headquartered in Milan, Augusti Maximian ruled Italy and Africa. Maximian’s Caesar was Constantius who ruled from Trier. His territorial responsibility was the least populated portion of the empire: Britain and Gaul.

With the establishment of the Tetrarchy, no emperor spent any length of time in Rome. On the other hand, as a result of Diocletian’s leadership and more skilled and competent administrators, the eastern empire, now known as “Rome,” would stand for a thousand years until 1453 when the Ottoman Turks conquered Constantinople.

Let’s examine a manufactured image of Diocletian’s revolutionary political system. We find the sculpture not in Constantinople’s philadelphion (open space), where in 305 CE it had been attached to a column by an unknown artist, but in Venice, Italy!11 After looting Constantinople in 1204, Crusaders brought the 51” tall porphyry (purple marble) sculpture of the Four Tetrarchs to Saint Mark’s Basilica and had it built into the façade of the building [image 7.18].12 Dressed in military garb, the sour, heavy and dour rulers anxiously grasp their swords with their free hands [image 7.19]. In this symbolic representation we can distinguish the bearded Augusti (emperors) [Image 7.20] from the clean-shaven Caesari (subordinates) [image 7.21], but it is impossible to distinguish Diocletian from Maximian. There are no identifiable, individual features. Individualism is gone!

Individualism was not the only value to be disappearing. Neither were the figures on this sculpture scaled according to Pythagorean proportions, appreciated as recently as 106-113 CE on Trajan’s Column [images 7.9 and 7.22]. In a swift turn of events, Humanism was also gone.

The four arcons were embracing in a desperately hoped-for unity. In theory, the colleagues were supposed to act in concert with each other, issuing laws that were to be observed in both halves of the empire, while each was responsible for defending his own territory. In reality, the Eastern Empire flourished while the Western Empire struggled and neither gave much thought to helping the other. Each saw the other more as a competitor than as a teammate and both worked primarily in their own self-interest. This was not a portrayal of cooperative unity. This “brotherly love” is no more convincing than the Augustinian implementation of Pax Romana, or for that matter, than the declarative Ara Pacis had been to us. We must admit, that even in Roman times, pax and peace were not the same.

Before we leave Diocletian, it should be pointed out that he was very pious in his devotion to the Roman gods. It must have caused considerable family stress when both his wife, Prisca, and his daughter, Valeria, converted to Christianity. Furthermore, missing his chance to harness the dynamic element of Christianity for the benefit of the empire, Diocletian began the worst persecution in the history of Christianity. During the ten years of his “final suppression,” from 303-313, he issued several imperial edicts:

- He demanded sacrifice to the Roman gods. Noncompliance with this edict led to death or forced labor in the salt mines.

- With the aim of depriving Christians of their leaders and organization, clergy were imprisoned and made by torture to sacrifice to the gods.

- “Scriptures” were burned. That requirement raised a dilemma: which documents should be desperately hidden and which could be burned? Just what does a “scripture” look like? To get the authority off one’s back, some believers would turn over anything that looked like a “scripture.” Other individuals would be labeled as “traditores” for their compliance in surrendering holy writings. We can’t help but wonder about early writings which were irrevocably lost due to this edict.

- No Christian could hold Roman citizenship. Therefore, no one could hold a post in the imperial or municipal services, and neither could one appeal a judicial verdict.

- No Christian slaves could be granted freedom.

It may be argued that no 10-year period was more important for the fortunes of Christianity than this decade. But the persecution failed to force the majority of Christians to recant; instead, the growing popularity of the movement was attracting the kind of hatred that success breeds.

Diocletian retired in 305 and convinced Maximian to do so as well. According to Diocletian’s clear specifications for the Tetrarchy, the two Caesars were move up to the position of Augusti, but the army, and ambitions sons, preferred biological lineage to the non-hereditary succession that had been proposed. The next battle in this era of high treason will be another civil war between the usurper Maxentius (son of former Augusti Maximian and the son-in-law of Caesar Galerius) against the usurper Constantine (son of the Caesar Constantius I Chlorus).

References:

1. Photo by the author, Kathleen J. Hartman, 2018. CC BY-NC 4.0 License

2. Ibid.

3. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Trajan%27s_Column_Panorama.jpeg

4. Photos by the author, Kathleen J. Hartman, 2018. CC BY-NC 4.0 License

5. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:AugustusCoinPudukottaiHoardIndia.jpg

6. Artstor, library-artstor-org.libdb.ppcc.edu/asset/ARTSTOR_103_41822003339007

7. Public domain at en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Verona_Arena#/map/0

8. Photo by the author, Kathleen J. Hartman, 2007. CC BY-NC 4.0 License

9. From 60-53 BCE Gaius Julius Caesar, Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus and Marcus Licinius Crassus had been joined in a rule-of-three political alliance known as the Triumvirate.

10. Public domain at upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/0/07/Tetrarchy_map3.jpg

11. Public domain at Khan Academy “Portraits of the Four Tetrarchs,” at https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/ancient-art-civilizations/roman/late-empire/v/tetrarchs

12. Named for the Greek word for “purple,” porphyry is very close to the color of the fabulously expensive shellfish-based purple dye which was used for the purple stripe on the tunics and togas of the Roman Senatorial class. So, porphyry meant Rome and the power of the Caesars. Of course, the Crusaders thought the sculpture belonged here in Italy, closer to “real” Rome, than in pillaged Constantinople!

13. Photo by the author, Kathleen J. Hartman, 2016. CC BY-NC 4.0 License

14. Ibid.

15. Ibid.

16. Ibid.

17. Photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0. Accessed at www.khanacademy.org/humanities/ancient-art-civilizations/roman/early- empire/a/column-of-trajan

18. Photo by the author, Kathleen J. Hartman, 2016. CC BY-NC 4.0 License

19. Ibid.

20. Public domain at khanacademy.org/humanities/ancient-art-civilizations/roman/early-empire/a/column-of-trajan