7.3 ANTICIPATING BYZANTINE CULTURE

What do these images hold in common?

If you are remarking about the drama of the “big eyes,” you are right on target!

Their huge, deep-set eyes with an arresting gaze address us, the viewer, directly. In ancient times the eyes were an indication of godliness. The eyes were considered “the window to the soul” and the clear eye was believed to penetrate darkness. Egyptian, Greek and Roman traditions blended together to create these impressive images. These three traditions will also be the foundation of Byzantine culture.

During the 1st to 3rd centuries CE, when Egypt was a province of the Roman Empire, painted shrouds or portraits were prepared to accompany the mummies. Paintings of this type, often called Faiyum portraits (though not all of them came from the Faiyum oasis 15 miles south of Alexandria), were typical products of the multicultural, multiethnic society of Roman Egypt.

These portraits were finely executed in encaustic paint (heated beeswax to which pigment has been added) on wood or stuccoed linen. Other ingredients such as egg, resin and linseed oil were also added, allowing artists to depict the inhabitants of the Greco-Roman period of ancient Egypt in exacting detail. These were portraits of individuals in a multi-racial society; they are the faces of people you might know. They may (or may not) have been painted during the person’s lifetime and first displayed in the home while the individual was alive.

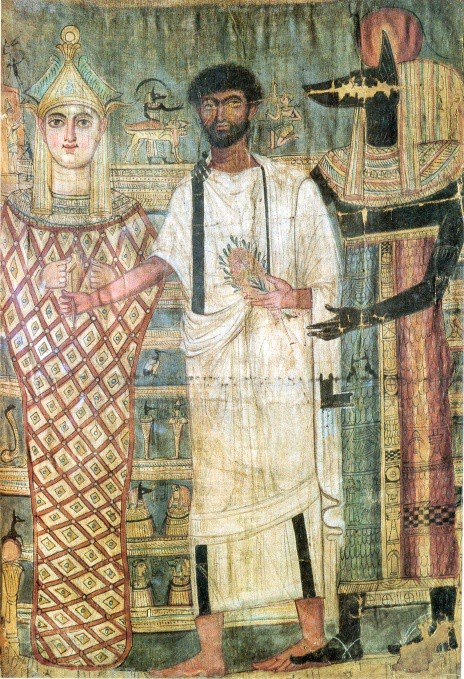

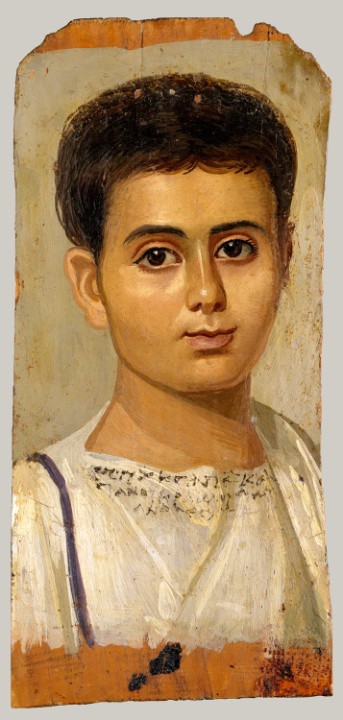

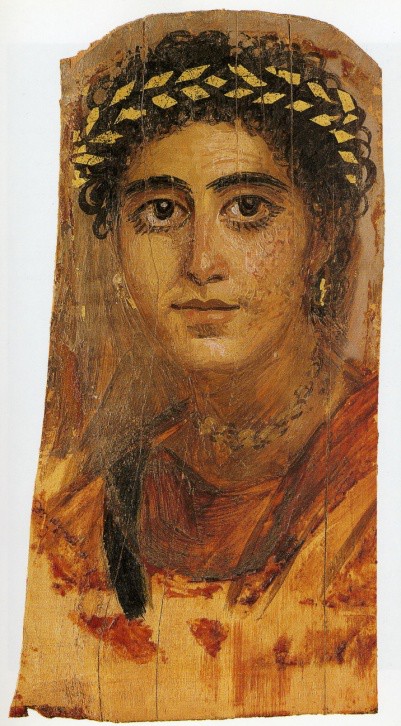

The Faiyum portraits exhibit many Egyptian characteristics. Of foremost importance is the continuing Egyptian practice of preserving the body. Earlier mummies had idealized masks modeled in plaster or cartonnage to represent the face. In the Faiyum portraits the mask was replaced with a painted wood panel which was held in place by the linen mummy wrappings on the coffin [image 7.1]. The second Egyptian feature is to be seen on the Funerary Shroud [image 7.2] on which nearly life-sized portrayals of Anubis and Osiris flank the figure. The gods are both easily recognized because of their attributes (characteristic features). Anubis, on the viewer’s right, wears the nemes headdress with a lunar disk on his head, a proclamation of regeneration. Osiris, on the left, is symbolized by the scepter and the whip. The third standard Egyptian feature is the frontal depiction of gods, with the head and feet shown in profile. Having been judged righteous, the figure on the shroud is depicted in this forward-facing posture and is wrapped in a garment of the living. Only the hands and face are visible as he was transformed into the divine Osiris. The portrait of the so-called Young Woman in Red [image 7.4] displays the sparkling fourth feature; her image was gilded (probably after her death) to suggest the divine flesh of the gods. An additional Egyptian characteristic that you will often see was the enhancement of the eyes of the subject with “Egyptian blue,” a paint mixture of silica, lime, copper, and an alkali. Blue was associated with the sky and the river Nile, and thus came to represent the universe, creation and fertility.

Greek influence is evident in the contrapposto turn-of-the-head seen in each of these. The high cheekbones of the Young Woman in Red and the repetitive ringlets in her hair are typical Greek conventions. The writing on Eutyches‘ toga is Greek [image 7.3], which was the common language of the eastern Mediterranean at the time.v The encaustic technique had first been developed by the Greeks as a wax paste to fill the cracks on ships. Later they discovered they could paint fearsome faces on the ships. The liquid/paste was applied on prepared wood and much later encaustic was used on canvas and other materials.

The Hellenistic influence is clear. Egypt had been part of the Hellenistic world since the 332 BCE conquest by Alexander the Great. The naturalistic shadows of Hellenistic individualism allowed the commemoration of old men, young children, athletes and pagan gods. The portrait displayed within the mummy panel [image 7.1] captivates us with his large deep-set eyes and a down-turned mouth. His downy moustache indicates that he was no older than his early twenties. The youthfulness of Eutyches [image 7.3], depicted under a bright source of light, entices us to mourn his death. The Young Woman in Red [image 7.4] looks at the viewer with large serious eyes which are accentuated by long lashes. A mass of loose curls covers her head, and some strands fall along the back of her neck on the left side. Framed by the black hair, deeply shadowed neck, and dark red tunic, her brightly lit face stands out in appealing youthfulness.

We can’t help but admire the Roman influence of curly hair, white tunic, purple clavus (vertical stripe) and mantle draped over the left shoulder, as seen in both images 7.2 and 7.3. Specific clothing, footwear and accoutrements identified one’s gender, status, rank and social class. The sparkling jewelry and gold wreath of the Young Woman in Red [image 7.4] follow contemporary Roman court fashion. Furthermore, we are reminded of the whole tradition of Roman portraits we have seen of distinguished Roman citizens such as Caesar Augustus.

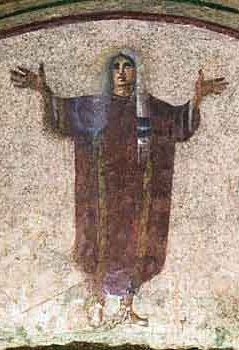

The Individualistic features of people you might know, with contrapposto positioning, dramatic shadow and attractive Humanistic bodies, disappear in the Byzantine Era, but those huge, mystical eyes are an easily recognized feature of the Byzantine icon. We can witness the shift in the third century Catacombs of Priscilla, a Greek chapel north of Rome. We call the figure Donna Velata (“Lady of the Veil”) [image 7.5] out of custom, but is the person male or female? There are no natural curves, no telling shadows, no three- dimensional space. The figure certainly does not suggest a humanistic contrapposto stance. This is not a portrait, there are no attributes, it is not a recognizable individual. All we really know about Donna Velata is to be witnessed in the deep-set eyes, and that the figure stands in the orant position, the Greek position of prayer.

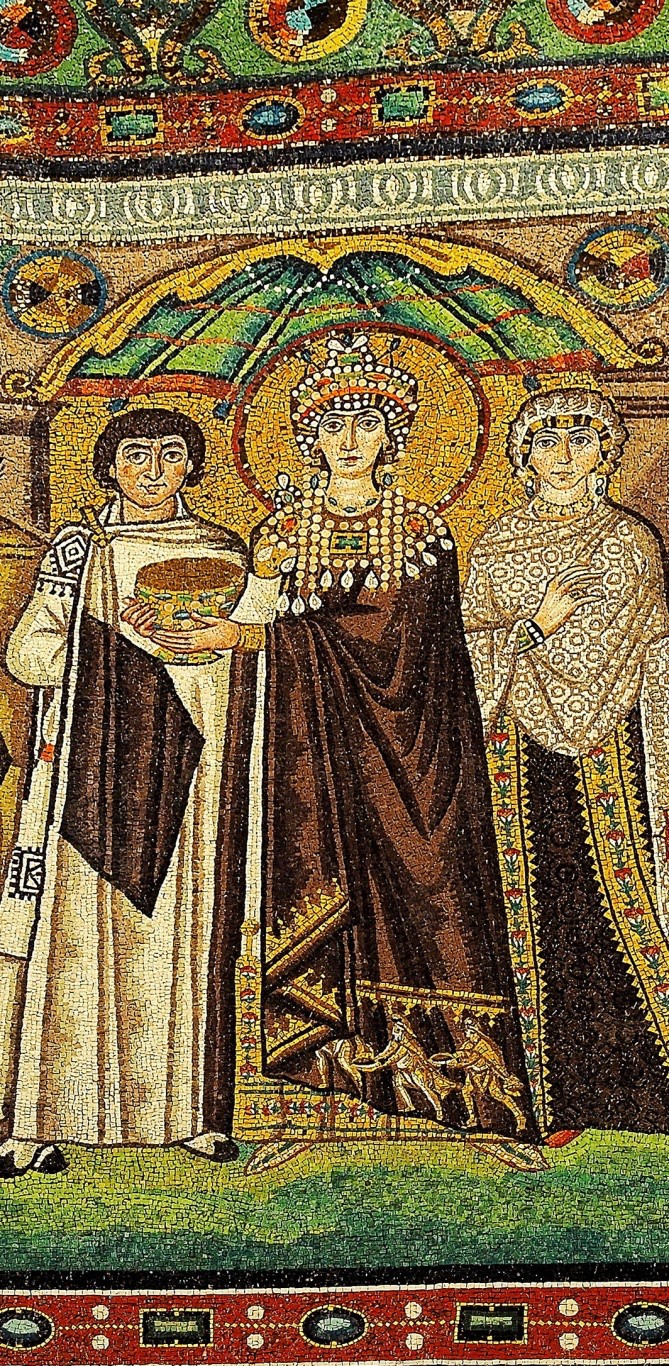

You will be witnessing those same mysterious eyes when you meet with the Emperor Justinian and the Empress Theodora at the Basilica of San Vitale in Ravenna [images 7.6 and 7.7]. Except for their identifiable clothing, which was distinctively important to the Romans, Individualism and Humanism are values of a bygone age. The new look of the mystical Byzantine Era is in those clairvoyant eyes.

References:

1. Unknown artist, Scanned by Szilas from the book J. M. Roberts: Kelet-Ázsia és a klasszikus Görögország (East Asia and Classical Greece). Public domain at upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/d/d2/Shroud_from_the_time_of_the_Ptolemaic_dynasty.jpg

2. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Public domain at www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/547697

3. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Public domain at www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/547951

4. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Public domain at www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/547860

5. According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art (www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/547951) “Scholars do not completely agree on the inscription’s translation. The boy’s name (‘Eutyches, freedman of Kasanios’) seems indisputable; then follows either ‘son of Herakleides Evandros’ or ‘Herakleides, son of Evandros.’ It is also unclear whether the ‘I signed’ at the end of the inscription refers to the painter of the portrait or to the manumission (act of freeing a slave) that would have been witnessed by Herakleides or Evandros. An artist’s signature would be unique in mummy portraits.”

6. Public domain at smarthistory.org/santa-maria-antiqua-sarcophagus/

7. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Emperor_Justinian_and_Members_of_His_Court_MET_LC_25_100_1a-e_s01.jpg

8. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Theodora_mosaik_ravenna.jpg