6.7 Religion During Pax Romana

As empires go, Rome was not particularly bad. It was better than the empires it replaced, and it was better than most of those which replaced it. The empire had a system of law. It had stable order, which promoted trade. Public works projects built roads, baths, temples and markets.

Beneath the grandeur, however, lay a decaying social system where the poor, sick, widows and orphans were left out. Roman urbanization and commercialization had led to both the economic boom of Pax Romana and to destitute peasants. Many had come to the city from rural farms when they had been replaced by slave workers. Here they lived in urban squalor in one of the 46,000 unregulated five-six story insulae. The insula apartment had no chimney, no lighting and no water supply or drainage (therefore, it was easier to just toss the contents of the chamber pot out the window). Jobs might be very difficult to find and prices were high. There was no pension system, unemployment insurance or medical protection. Social security was nonexistent for the urban poor. Some became clients of wealthy patrons whom they provided with political support in return for handouts. Others relied on a grain dole that the government instituted in the late Republic and continued during the Empire.

It was not a pretty sight. It was a world of unrelenting cruelty. Who today could condone the sight of men and women being fed to beasts as people of all classes shrilled their delight? To the Romans, the spectacle was a just punishment for lawbreakers.

Roman religion was not a matter of ethical behavior, but of honoring the gods who could protect and assist you, who could potentially influence the outcome of any process that was risky, uncertain, or incomprehensible. It was essential that the gods be given what was “due” to them, that proper ritual and performance be observed. With proper ceremony the gods could grant health and prosperity.

Roman society was a polytheistic society. The vast majority of people were pagans adhering to various cults (forms of worship). None of the gods demanded exclusive attention. There were no sacred scriptures, compulsory beliefs, distinct clergy or obligatory ethical rules. The state tolerated all religions provided they were not immoral or politically dangerous.

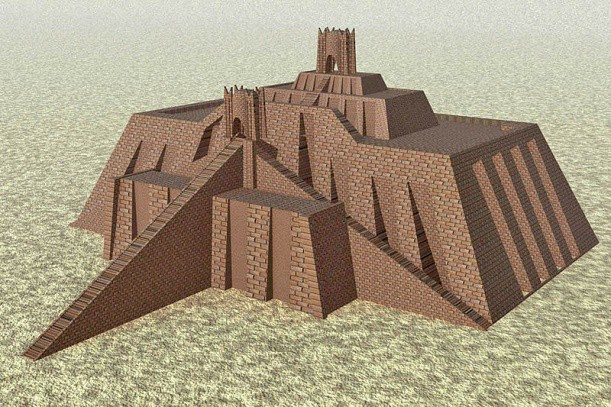

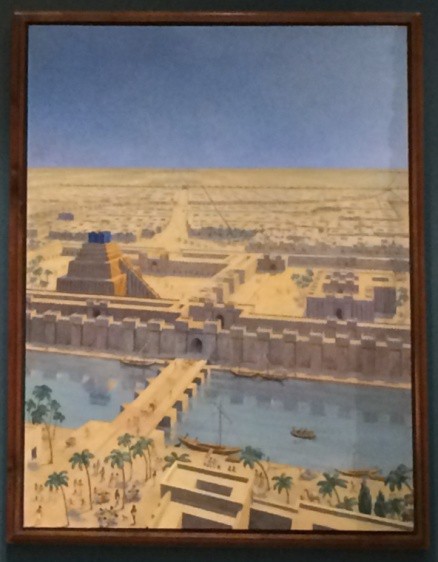

Ah, but we are in Rome and when in Rome rank and status count. The many gods were not equal in prestige to one another. There were distinct ratings of gods, similar if you will, to the levels of a Sumerian ziggurat [images 6.66 and 6.67]. In the ziggurat, seven stories provided reception and accommodation rooms for the gods. In coincidental parallel analogy, there were also seven classes of Roman gods.

Emperor Gods

The highest ranking class was the god of the empire. As the pater patriae the emperor/god was responsible for overseeing Rome’s relationship with the other gods.

Emperor worship had been introduced by Augustus Caesar as a unifying force for the Empire. After 100 years of social unrest, including 20 recent years of civil war, the populace was ready for peace. “Thanks be to god!” But since Augustus had done it, was he not god? He had brought peace, security, and prosperity. Was he not the savior of the world? Moreover, he had been Divine. His father was Apollo, and his mother the mortal Atia. Therefore, he was the son of a god. In demonstration of his divinity, he had been seen ascending to heaven after his death.

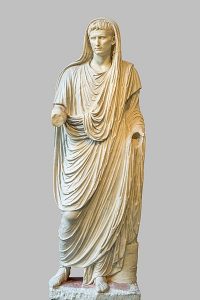

Earlier you witnessed hints of his divinity in the sculpture known as Augustus of Prima Porta [image 6.68]. The sky god (Caelus), the sun god (Sol), the goddess of the hunt (Diana), the earth goddess (Tellus) and Apollo are all depicted on his military cuirass. The most obvious sign of his divinity is Eros, the son of Venus, riding triumphantly beside him on a dolphin. Eros reminds the viewer that Augustus is from the family of the Julians, who claimed descent from Venus. In image 6.69 he is presented as the Pontifex Maximus (“high priest,” but literally the “great bridge tender”).

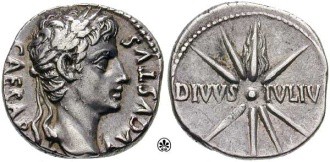

Adding to Augustus’ dignity was his relationship to his great-uncle and adoptive “father” Julius Caesar. Four months after Caesar died, a grand funerary festival named Ludi Victoriae Caesaris (“Praise to the Victorious Caesar”) had been organized in his honor. During the festival, a very bright object appeared in the sky and transfixed the people of Rome. Since Caesar once claimed that he was a descendant of the goddess Venus, many Romans concluded that Caesar had become a deity and that the bright object was actually a new star containing Caesar’s soul. More than 100 years later, famous Roman historian Suetonius wrote, “A star shone for seven successive days, rising about the eleventh hour, and was believed to be the soul of Caesar.”

Augustus used this event to emphasize his familial connection with the deified Julius and to proclaim the role of his divine credentials role in heralding a new age of peace and prosperity [image 6.70]. He also had a basilica-styled temple built in his “father’s” honor in the Roman Forum. The Temple of Divus Iulius (Temple of the Deified Julius, aka Temple of the Comet Star) was built in 42 BCE and dedicated in 29 BCE by Augustus for the purpose of fostering a “cult of the comet.”

On the very personal level, emperor worship structured time, giving civic holidays and days off. Civic magistrates covered the obligations of 59 holidays a year in honor of various gods, plus 34 days of games for various pretexts, plus 45 general feast days, plus various five day festivals to honor the emperors—in total there were 159 public holidays per year.

You have also met Trajan, who is, unfortunately, not very clearly depicted at the top of his column [image 6.74]. No matter: St. Peter now caps the column, having replaced the nude statue of Trajan. But the column is still relevant as a memory device for the deified Trajan. The 123 day Trajan-sponsored celebration which accompanied the conquest of the Daciens included both games and food. During that dedication 11,000 beasts were slaughtered at the Colosseum. Thus, even in the domestic rituals of life, Romans ended up paying service to the gods of the state, and therefore, to the state itself.

Great Gods of Greece and Rome

The great gods of Greece and Rome ranked just a little lower than the emperor gods. Many of these are familiar to you: Zeus, who was known as Jupiter in Rome; Athena (Roman Minerva); Poseidon (Roman Neptune); Hera (Roman Juno) and Apollo. You already know these as Greek gods; these Roman examples will demonstrate the Roman respect which they also held.

Gods of Specific Functions

Life was often lived “near the edge.” The primary concerns were the growth of crops and the avoidance of starvation. Ranking just a little lower than the great Greek and Roman gods were the gods of specific functions, such as war, the weather, flocks and the hunt, love, the crops, mountains, streams and forests.

Civic Gods

Just a little lower in status was the divine patron of one’s city. In Greek, Sumerian and Rome cities civic pride, financial interest and piety were all intertwined in the proper observance of the city god. You will recognize some of the locations.

Marduk rose from an obscure deity in the third millennium BCE to become one of the most important gods and the head of the Mesopotamian pantheon in the first millennium. He was the patron god of the city of Babylon, where his temple tower, the ziggurat, may have served as the model for the famous “tower of Babel” [image 6.80]. In the first millennium, he was often referred to as Bel, the Akkadian word for “Lord.”

The Mesopotamian moon god was known by the name of Nanna (Sumerian) or Sin( Akkadian). Sin was the father of the sun god,Shamash (Sumerian: Utu), and, in some myths, of Ishtar (Sumerian: Inanna). This ziggurat [image 6.67] was built by king Ur-Namma of Ur (r. about 2112-2095 BCE), the founder of the Ur III dynasty. The monumental temple tower was built of solid bricks.

Delphi was an important ancient Greek religious sanctuary sacred to the god Apollo. Located on Mt.Parnassus near the Gulf of Corinth, the sanctuary was home to the famous oracle of Apollo which gave cryptic predictions and guidance to both city-states and individuals. The temple of Apollo [image 6.81] was first built in the seventh century BCE, rebuilt after a fire in the sixth century BCE, and then rebuilt after an earthquake in the fourth century BCE.

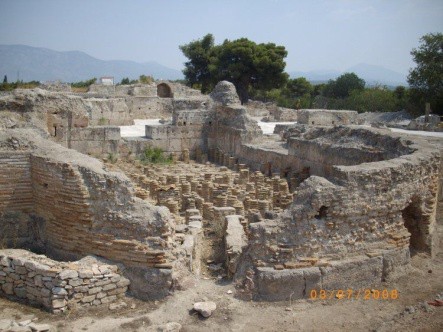

The city god of Isthmia was Poseidon. Unfortunately the sanctuary had been abandoned by the year 400 CE. Among the ruins which have been studied by archaeologists are the floor of the Roman bath and the hydrocaust (heating system) for that bath [images 6.82 and 6.83].

This Roman bust [image 6.84] dates form the second century CE. The helmet helps us recognize Athene, the patron goddess of Athens. Her idealized features and impassive face embody the “noble simplicity and quiet grandeur” that Johann Joachim Wincklemann (1717-1768), founder of the discipline of art history, considered the pinnacle of ancient artistic achievement.xxii Of course, her temple tops the Acropolis in Athens.

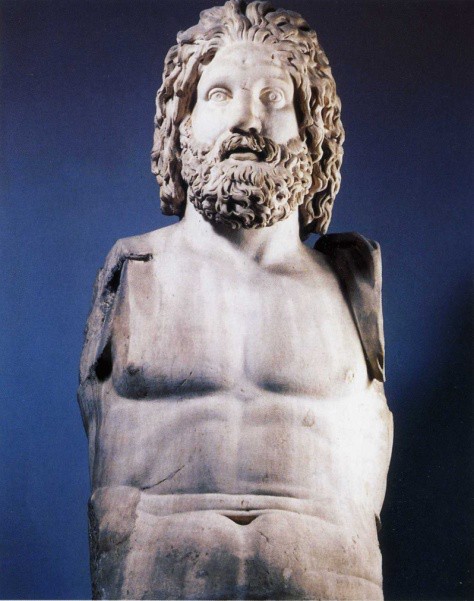

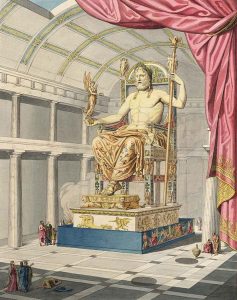

The fifth century Temple of mighty Zeus at Olympia had all of the characteristics we associate with a Doric temple: a peripheral forms with a frontal pronaos upon a platform with three steps, carved metopes and triglyph friezes, and a pediment.

The Chryselephantine (gold and ivory) statue of Zeus, sculpted by Phidias [image 6.85], was so lifelike that Byzantine emperor Theodosius II ordered the sanctuary destroyed in 426 CE. Earthquakes, flooding and possibly a tsunami did further damage.

Personal and Household Gods

Just a little lower, but closer to home, were the personal gods. These were no more consistently good, or merciful, or even just than the gods of the state, or those of Greco-Roman antiquity, or those of one’s city. The primary advantage to a personal god was that, as guardians of the family welfare, Lares (aka “Penates”) could be recognized in a home shrine [image 6.86]. A homeward-bound Roman received comfort knowing he/she was returning ad Larem (to the Lar).

Among citizens of the upper class the Goddess of Fortune [image 6.87] was especially popular. The Temple of Fortuna Virilis [image 6.88] dates from late in the second century-early first century BCE. It was the temple of Portunas, the goddess of the harbors. She rewarded talent and ambition with material well-being. This temple is still standing in Rome because in 872 the basilica was rededicated to Santa Maria Egiziaca. It was believed that this specific Saint Mary had been a prostitute, born in 344 in Alexandria. She was often confused with Mary Magdalene, a follower of Jesus with a “tarnished reputation.”

Egyptian Gods

As Roman religion became increasingly ritualized and distant from the everyday life of the average person, and with a desire to escape the impersonal, authoritarian attitude of the Roman government, many Romans adopted the more personal, mystical beliefs of the peoples they had conquered.

After Augustus’ defeat of Marc Antony and Cleopatra, Egyptian gods offered spiritual renewal and salvation. The cult of Isis, mother of Horus, was adopted by some [images 6.89-6.92]. Remarkably attentive, she would respond when one was in trouble. As her cult spread she was identified with nearly every goddess of the known world. Vespasian (r. 69-70 CE) officially welcomed her and built a public temple. Justinian closed the last temple to Isis at Philae in the sixth century.

Isis was known by a myriad of names: Queen of the Inhabited World, Lady of All, Star of the Sea. In the same way that her son, Horus, was a symbol of rebirth, her tears were also a symbol of renewal and resurrection because they caused the annual Nile inundation.

“Greatest of the gods. First of all names, thou rulest over the mid-air and the immeasurable space. Thou art the lady of light and flame” (Second century CE Roman Eleusinian Hymn). Isis [image 6.92] is wearing the “basileion” (a headgear with the sun disk, crescent and horns of a cow). Plutarch declared, “the garments of Isis are dyed in rainbow colors because her power extends over multiform matter that is subjected to all kinds of vicissitudes.”

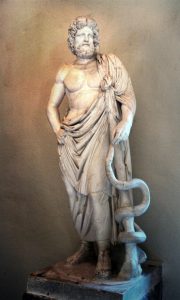

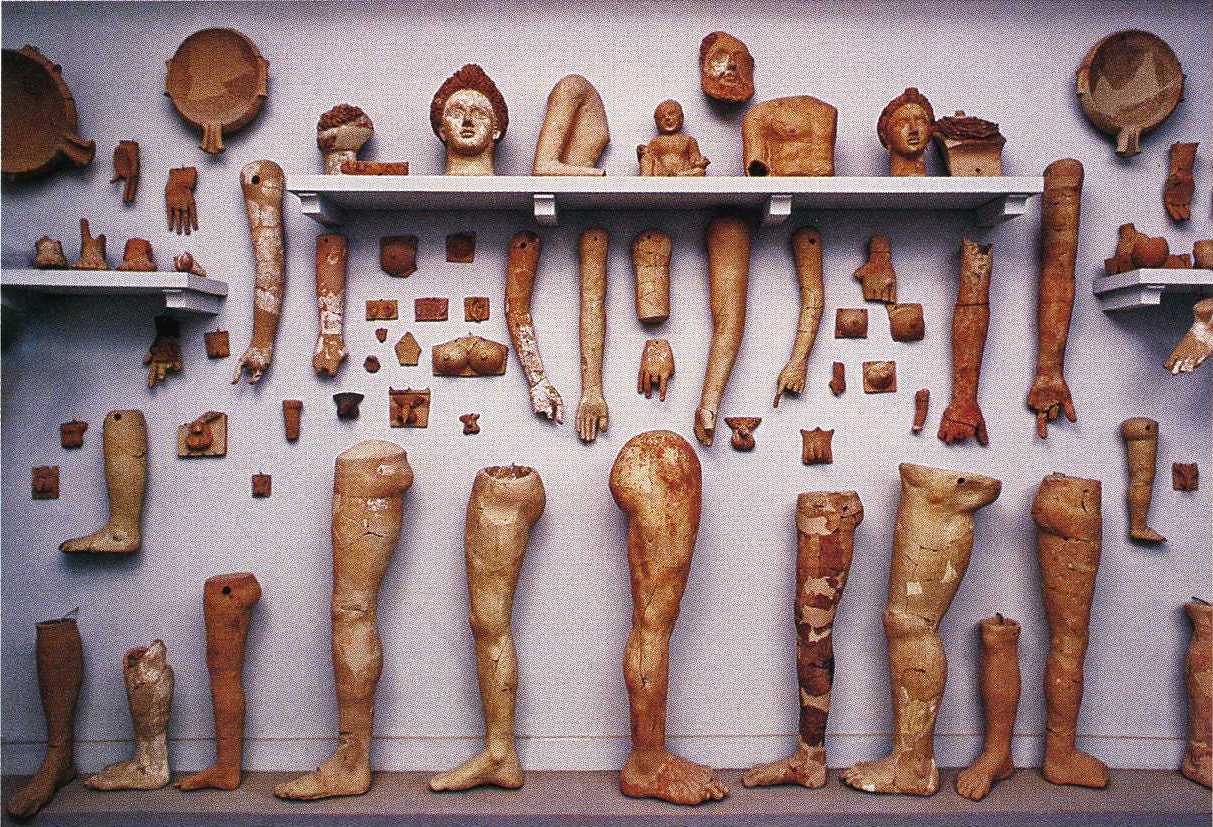

The cult of Asclepius also derived from Egypt. Originally known as Imhotep from Old Kingdom Egypt, he was recognized as the architect who created the Step Pyramid of Djoser [image 6.93], a new kind of architecture and an innovative symbol of power. He also discovered how to cut stone for the building of monuments. As his reputation grew the savant became revered as a scribe, a sage, statesman, physician, priest, astronomer, savior of Egypt from famine, as well as vizier to the pharaoh. In Greece he became known as Asclepius, the son of the god Apollo and the mortal Koronis [image 6.96]. According to the Homeric Hymn to Asclepius he surpassed all his fellow doctors for, in addition to being able to heal the sick, he could raise the dead. So many sick people cheated death that Pluto in Hades protested to Zeus. Pindar wrote that Zeus, in an attempt to maintain the balance between the Earthly and the Heavenly Worlds, killed Asclepius by throwing a thunderbolt at him. Zeus later relented: Asclepius was brought back to life and made into a god. Asclepius was brought to Rome in 293 BCE, where his serpent routed the plague.

Persian God

From Iran, the Persian Mithras was especially popular with the soldier-emperors and their troops in the western part of the empire. Mithras was known as the sol invictus (“God of the unconquerable sun”) and the, “the sun that returns to shine again.” When the Emperor Constantine declared Sunday as a day of rest, was he honoring the Christian God or Mithras? Mithras’ birthday, the Feast of the True Sun, is December 25, coinciding with the winter solstice. Pope Liberius recognized the holy day of December 25 as Christmas in 354.

Mithras is possibly linked to the Spanish cult of the bullfight.

In image 6.97, is Mithras dressed in a toga, a typical Roman attire? (No. He wears a “Persian” tunic, cloak and conical hat.)

The central episode of his life was the Tauroctonia (killing of the bull). Mithras seizes the bull by its nostrils and thrusts a knife into its side in the presence of a raven and a dog licking its wounds near a serpent. A scorpion chomps off the genital of the bull, from whose tail wheat ears emerge. Attending the scene are Coutes (with a lit torch oriented upward) and Cautopates (with a torch oriented downward). They, as well as the sun and the moon in the upper corners, represent extremes in vital cycles, beginning and end, dawn and sunset.

Phrygian God

The ancient Phrygian (modern day Turkey) Mother of the Gods was Cybele [images 6.98 and 6.99]. The Julian family, eager to emphasize their Trojan ancestry, promoted her origin from Pergamon.

During the Second Punic War (218-202 BCE) a Sibylline oracle commanded that Romans should welcome Cybele, the “great mother” of Mt. Ida in Asia Minor if they wanted to be saved from Hannibal. The goddess was escorted into Rome and housed in the Temple of Victory along with her Phrygian priests and wild music of rattling sistrums and cymbals.

Simulating her blessing of the earth’s fertilization by rain, the yearly festival of Cybele in Rome ended with a procession that carried the silver cult image into a river for ritual bathing. However, some authorities viewed with suspicion some of the rituals conducted in her honor. “How”, they reasoned, “could she claim to be a fertility goddess when her priests castrated themselves in a public orgiastic ceremony?”

Over the years, Cybele became identified with Rhea (mother of the Olympians), and then eventually she evolved into Tellus, who was a union of mature motherhood and womanly beauty, tenderness and grace [image 6.100]. Tellus is the root of the word “Italy.”

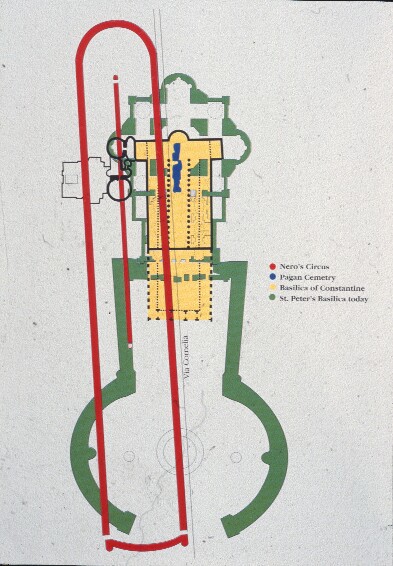

The Temple of Cybele also underwent transformation. Having been identified as the site of Saint Peter’s martyrdom in 67 CE, Saint Peter’s Basilica in Rome was placed upon the site of the leveled Temple of Cybele.

In Rome, religion was widely inclusive. Everybody recognized that they needed the power of the gods and the gods seemed to be present everywhere. It was natural and obvious to worship many gods.

It should be remembered that although the gods knew a great deal, none of these gods was considered omnipotent. None was concerned with ethics. They certainly were not transcendent. None was concerned with the afterlife. None of these created the universe; they were just a part of it, as were their followers. They were not even credited with creating humans, and they certainly were not a loving parent. With rare exceptions, the relationship between these gods and humans was not based on mutual love. All could take on human characteristics for a while, or they could be aloof and remote.

Each of these gods stressed personal fulfillment rather than involvement in the community, a set of ethics or moral behavior. None of these religions had a creed, a set of required beliefs. None had any authoritative scriptures, distinct clergy or obligatory ethical rules. There was no belief that only one was “true.” Because they were tolerant of each other, no individual could be labeled as a “heretic.” Nor could one be required to follow “orthodox” requirements.

Significantly, as the Greek historian Herodotus had pointed out (c. 425 BCE) these eternal gods had nothing to lose. They could live forever, and therefore they lacked human vulnerability. They could not demonstrate nobility of character, or courage, or self-sacrifice. These qualities, known as kleos, Herodotus maintained, belonged solely to humans.

Jewish God

Rome also housed a large minority population of émigré Jews who stood by the tenets of their faith and practiced its rituals. They comprised possibly 7% of the population. The Jewish tradition had nearly everything the polytheistic society lacked. They had a creed, the “shema:” “Hear, O Israel, the Lord our God, the Lord is One.” They had scriptures: the Pentateuch. They had distinct clergy through the tribe of Levi. They accepted a mutual covenant with God, believing that God had chosen them to be his people, and in response they had chosen God. As the “chosen people,” they held a strong commitment to social justice. They felt they were expected to set the example of the higher moral standard of a God who demanded ethical behavior. And they were monotheistic, insisting on the worship of only one God.

The Jews may be introduced to us by way of two funerary slabs [images 6.102 and 6.103], both of which were unearthed during archaeological digs as the modern city of Rome expanded.

Related resource on Mystery cults in the Greek and Roman Worlds at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

References:

1. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ziggurat_of_ur.jpg

2. Public domain at upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/9/95/Great_Ziggurat_of_Ur.JPG

3. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Statue-Augustus.jpg

4. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Augustus_Pontifex_Maximus.jpg

5. Public domain at en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caesar%27s_Comet

6. Daniel Levine, University of Arkansas. sites.uark.edu/dlevine/biers8-1/

7. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Iuno_Petit_Palais_ADUT00168.jpg

8. Photo by the author, Kathleen J. Hartman, at the Archaeological Museum of Naples, 2016.

9. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Trajan%27s_Column_Panorama.jpeg

10. Photo by the author, Kathleen J. Hartman, at the Nelson-Atkins Art Gallery, Kansas City, MO., 2006. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

11. Photo by the author, Kathleen J. Hartman, at the Louvre Museum, 2014. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

12. Photo by the author, Kathleen J. Hartman, at the Chicago Art Institute, 2016. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

13. Ibid.

14. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Third_Style_fresco_depicting_Pan_playing_the_flute_accompanied_by_a_nymph_playing_the_lyre,_f rom_the_House_of_Jason_in_Pompeii,_Naples_National_Archaeological_Museum_(17322137452).jpg

15. Public domain at upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/9/95/Great_Ziggurat_of_Ur.JPG

16. Photo by the author, Kathleen J. Hartman, 2017. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

17. Photo by the author, Kathleen J. Hartman at the Oriental Institute, Chicago, 2019. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

18. Public domain at www.ancient.eu/image/234/roman-bath/

19. Public domain at www.ancient.eu/image/255/roman-bath-house/

20. Photo by the author, Kathleen J. Hartman, Art Institute of Chicago, 2013. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

21. Public domain at Quincy, de. “Statue of Zeus, Olympia.” Ancient History Encyclopedia. Ancient History Encyclopedia, 28 Jul 2016. Web. 26 Nov 2020.

22. Johann Joachim Winckelmann, Reflections on the Painting and Sculpture of the Greeks, 1765.

23. Photo by the author, Kathleen J. Hartman at the Denver Museum of Science and History, 2012. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

24. Dr. Jeffrey A. Becker, “Temple of Portunus, Rome,” in Smarthistory, August 8, 2015, accessed November 22, 2019, smarthistory.org/temple-of-portunus/

25. Photo by the author, Kathleen J. Hartman at the Denver Museum of Science and History, 2012. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

26. Public domain at www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/548310

27. Public domain at upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/e/eO/Musee_Pio_Clementino-Isis_lactans.jpg

28. Public domain at en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lychnapsia

29. Photo by the author, Kathleen J. Hartman, at the Museo Nazionale Romano, Baths of Diocletian, 2017. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

30. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Egypt-12B-021_-_Step_Pyramid_of_Djoser.jpg

31. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Imhotep-Louvre.jpg

32. Photo by the author, Kathleen J. Hartman, Sanctuary of Asclepius at Epidaurus, 2017. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

33. Ibid.

34. Photo by the author, Kathleen J. Hartman, at the Museo Nazionale Romano, Baths of Diocletian, 2017. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

35. Public domain on www.metmuseum.org/toah/works-of-art/97.22.24/

36. Public domain at Kleerup, Dave &. M. H. /. “Cybele.” Ancient History Encyclopedia. Ancient History Encyclopedia, 04 Feb 2015. Web. 26 Nov 2020. Accessed at www.ancient.eu/image/3623/cybele/

37. Public domain at www.khanacademy.org/humanities/ancient-art-civilizations/roman/early-empire/a/ara-pacis

38. Courses.washington.edu/rome250/gallery/Rome%20wk%204/21%20St%20Peters%20&%20Nero’s%20Circus.jpg

39. Photo by the author, Kathleen J. Hartman, at Museo Nazionale Romano, Baths of Diocletian, 2017. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

40. Ibid.