6.5 Roman Architecture and Philosophy

The peace produced by the Pax Romana enabled Rome to focus on its greatest strength: architectural planning and public works. The insula and the domus served as private dwellings, but the emperors also built large practical facilities for Romans to gather together. There was no middle class but the millions of lower class Romans depended on government facilities and programs to survive. The government provided food distribution systems, recreation, entertainment, roads, bridges, police and fire protection, water, sanitation, and some of the first hospitals in the western world.

A safe clean water supply was critical for the health and happiness of the city. Aqueducts were developed as part of city planning. Some aqueducts were built as early as the 4th century BCE. When Roman armies conquered new territories, one of the first things they did was to build clean and abundant water delivery systems. One example is the Pont du Gard which was constructed by Agrippa in 18-19 CE in Nimes France. It carried water more than 30 miles to the city using a system of gravity flow and a gradual decline over long distances. A fall of 6” per 100’ was best and detours were made to avoid a sudden drop.

The bridge spans 900’ of the river. Each large arch spans 82’ and is made of uncemented blocks weighing more than two tons. Note image 6.38 which shows the stone projections built into the structure when the blocks were laid allowing the builders to secure scaffolding as they worked. A block and tackle was used to raise the stones the 160’ to the top layer. The lower arches are 65’ high and the upper arches are 28’ high. The smaller arches are placed in groups of 3 over the larger arches, manifesting the engineer’s sense for the aesthetic as well as the practical.

The 4’ water channel in the top is shaped with concrete and is covered by slabs of stone, so one could walk the full length of the aqueduct on top of the channel. This aqueduct supplied the city of Nimes with enough water for 100 gallons per day per person. The middle section could also be used as a foot bridge. Structures like this convinced people in the provinces that coming under Roman rule was to their advantage. Evidence of Roman aqueducts can also be seen in Spain, Greece, North African and Turkey.

Water from the aqueducts was used for public fountains and baths. The city of Rome had eleven aqueducts which brought water from as far as 57 miles away. Visitors to Rome today flock to see the Trevi Fountain which is supplied with water by the Aqua Virgo, constructed by Agrippa in 19 CE and they can fill their plastic water bottles with water from the ancient water system.

Another major destination for all of the water brought into the cities was to supply the public baths. Only the very wealthy had private baths, but there were more than 800 public baths located conveniently throughout the city. The Baths of Caracalla, built in 215 CE are a good example.

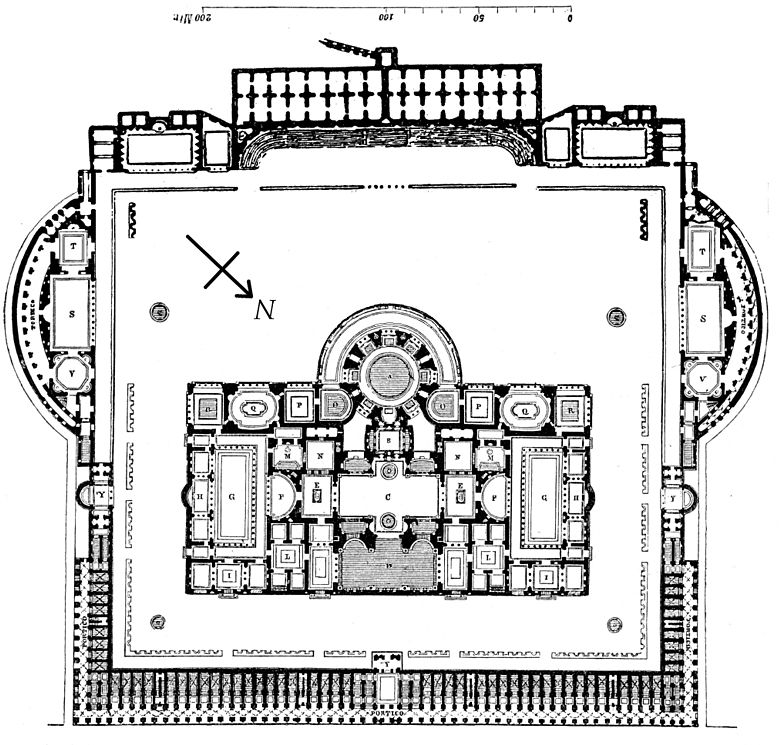

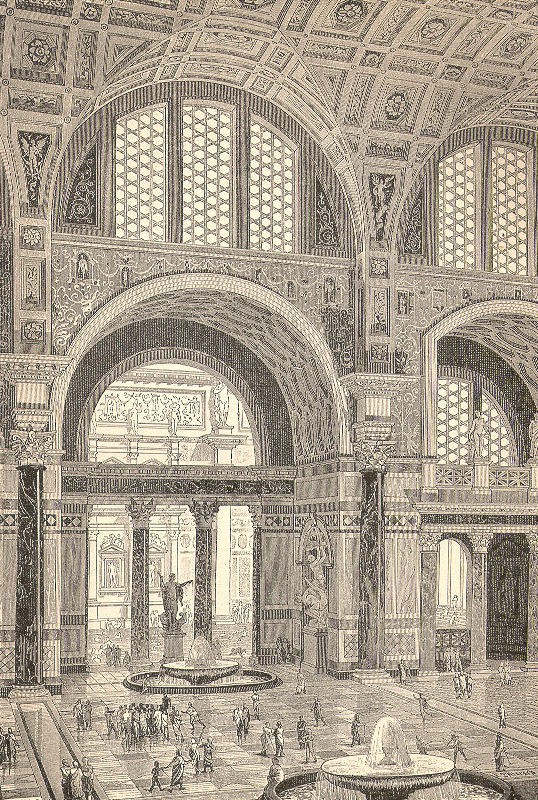

An important thing to notice in this drawing of the thermae, or Baths of Caracalla is the enclosure of a large area of interior space. This is a different way to think of space. The Greeks built their edifices to be seen as a backdrop for their ceremonies. The Romans built to enclose space for human use. We will notice this same way of thinking in the Pantheon and the Coliseum. The bath was built in 215 CE and is 750’ by 350’ with symmetrical placement of the pools. There are pools of different water temperatures, steam baths, dressing rooms, lecture halls, and exercise rooms. Slaves were available to scrape oil from the body with a strigil to remove the sweat and dirt from the body before bathing. There were different assigned hours of the day for men and women to use the baths and masseurs were available to soothe muscles and depilitators to pluck unwanted hair from the body. Other buildings in the area were shops, restaurants, and libraries. The subterranean corridors were wide enough for vehicles, storerooms, heating chambers, and housing for the slaves and stokers who kept the water flowing. A heating system circulated hot air through tubes and hollow bricks beneath the floors and sometimes in the ceiling vaults. The baths were created at state expense and for less than a penny a guest could stay all day. To the Romans the baths were an indispensable part of civilization and an important way to keep the masses happy.

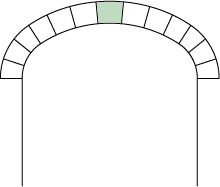

Romans architects were able to build these large enclosed spaces because of their use of arches and vaults. The use of the vault was known in earlier civilizations, but it was Roman ingenuity that really developed it. One of the major benefits of arches and vaults is that more light can be incorporated into interior spaces. See image 6.44 which shows a simple arch. Note the keystone at the top of the arch, and note that the stress or weight is thrust down either side of the arch allowing the weight to be distributed evenly. See the image of the Basilica 6.45 that depicts a several short barrel vaults, which are really just simple vaults lined up together. In the barrel vault the edges of the half cylinder rest directly on the walls which must either be thick enough to support the weight or must be reinforced with buttresses. When we talk about Romanesque architecture we will get back to this discussion of arches and vaults.

The other important tool used by the Romans was their development of the use of concrete. Romans were masters of the use of this building material. Concrete is made of aggregate which can be broken pieces of brick, small rocks, and volcanic dust mixed with lime and water. The addition of volcanic ash made the concrete slow drying and strong.

Excavations today show that many of the stones cracked but the concrete did not. Romans mined a special volcanic dust called pozzalona and used it as the binder. The only reason modern concrete stronger than Roman concrete is because we use metal bars to reinforce it. Romans also discovered that they could pour concrete in underwater harbor structures and it would set and even become stronger. The exterior face of their concrete structures was often covered with marble casing, stucco, or plaster because they liked the look of it better than the look of a concrete surface.

Large public gathering places are a hallmark of the Roman Empire. Many of the emperors created markets for the population to sell goods to each other. One example is Trajan’s Market, which might be called the world’s oldest shopping mall. It is a six-story market and public area used for shops, offices, and open stalls. They sold a huge variety of food, clothing and other everyday goods as well as silk, spices, ivory and jewelry imported from around the empire. The markets were run by the lower classes and the slaves since the upper class was theoretically not allowed to make money selling goods.

Roman emperors sought multiple ways to leave their mark on Rome and other cities in the empire. Trajan, for instance, erected a 128 foot column in the market between the library of the east and the library of the west. Trajan’s Column was carved and installed between 106 and 113 BCE and was created to commemorate his victory over the Dacians. In it there are depicted 150 separate episodes of Trajan’s life.

The images on the column read like a continuous comic book and could be compared to the frieze on the Parthenon in Athens. Each new scene begins with a symbol, perhaps a tree, or a building or another picture of Trajan. From it we can see his soldiers, who were actually the construction crew, setting up camps, building bridges, and putting up the infrastructure that would support that army. In figure 6.48, note the large bearded man under the bridge. It is a personification of the god of the river Danube, supporting the bridge so Trajan’s army can cross a reference to the belief that even the gods were helping Trajan win the war. The column’s base is circled by a victory wreath and below that is a collection of defeated weapons and military armor indicating the victory over the defeated Dacians and the strength of the army. This was not just about battles; it was also about the power of Rome to build lasting structures that elevated not only Trajan, but Rome.

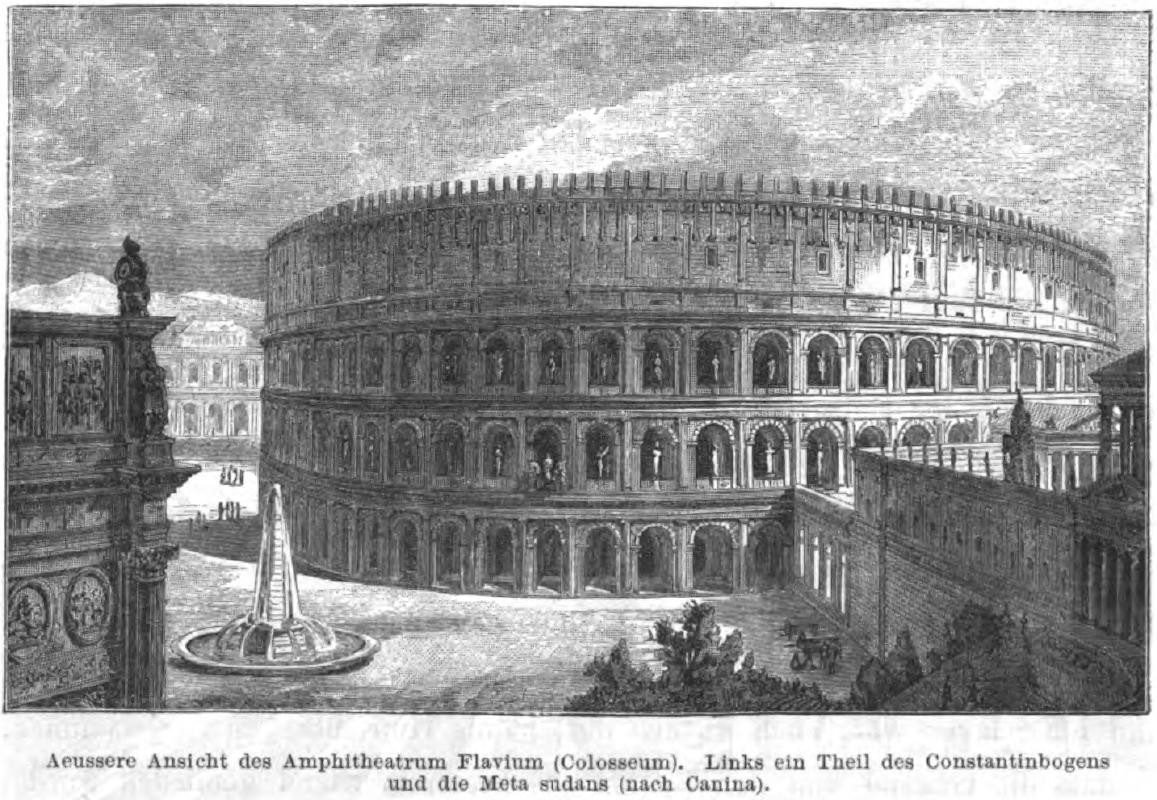

The citizens also liked to be entertained. Originally known as the Flavian Amphitheater because of the huge monument to Flavius erected there, the Coliseum was built by captured Jewish slaves and dedicated in 80 CE. It was built on land confiscated by Nero after the fire, but Vespasian cleverly returned the land to the use of the general population by creating a public place of entertainment. The building is shaped like two Greek amphitheaters facing each other around a central arena, the word for sand or beach, since the floor was covered with sand to soak up the blood. Most cities had an arena, and they can be seen all over the Roman world. Some of these structures are still in use today.

The Coliseum in Rome was built to house public games at the expense of the emperor. They celebrated holidays of which there were many. For instance, in the year 41 CE there were 159 holidays, 93 devoted to games provided for the public. Its capacity was about 50,000 people and it provided an inexpensive place to get away from the squalor and noise of the city for the day. Spectators were protected from the sun by a canvas awning held in place with poles and deployed by sailors pulling ropes to the beat of drums. Fast food was sold much like it is in our sports stadiums today. There were battles between gladiators, battles with animals, and even a real sea battle fought on the flooded floor on the 100 day opening ceremony which included sinking ships and drowning sailors. Remember from your studies of the Greeks that they did not want to show a death on stage. By contrast, Roman entertainment included the loss of thousands of lives in their games as a testament to their focus on realism rather than idealism.

Technically the Coliseum is a masterful use of arches, vaults, and concrete. The edifice is 161’ high, 620’ long, and 500’ wide. Access to the interior is through many numbered gates, and when you bought your ticket for a specific gate, it might even come with a door prize of a slave. The many doors made it possible for large numbers of citizens to enter and exit quickly. Basement cages held the animals and people who were to perform or die that day. Tunnels led to trap doors which opened onto the floor of the arena. The decorative scheme of the outer wall is based on the Greek orders: Doric columns are on the bottom level, then Ionic columns, then Corinthian columns, and the top level is flat pilasters. Today much of what we see is the result of nearly two thousand years of damage caused by weather, earthquakes, and plunder. When times were hard, people of the middle ages and the Renaissance came to this building to remove blocks, panels, and metal coffers to reuse them in their homes and public buildings.

One of the best preserved monuments to have survived from ancient Imperial Roman times is the Pantheon. Dedicated in 120 BCE, the original building was erected by Agrippa in the time of Augustus, but today we see the reconstructed version built by Hadrian. We know when it was built by the stamps made in the wet clay of the bricks used to make it. The Pantheon was built to house the statues of the planetary deities of Rome and the deified emperors. If you drew imaginary lines, the building would form a geometrically perfect sphere. It is 143’ high, which is higher than St. Peter’s Basilica at 140’ and higher than the cathedral of Florence at 137’. Hadrian loved to greet his guests here. It must have been very impressive then, as it is now.

The decorative pediment on the front porch of the Pantheon is supported by monolithic marble columns imported from Egypt and topped by Corinthian capitals, but the building does not rely on these columns for structural support. The interior of the building is a circular drum made of concrete which is 20’ thick at the springing of the dome and 5’ thick at the oculus in the ceiling. Wooden forms were built and the concrete was then added in a continuous pour process. So the dome is actually supported by the massive thickness of the concrete walls. This is another example of how Roman architects shaped the interior spaces for the use of many. The 27’ oculus, Latin for eye, is open to the sky and was intended to represent the sun in the dome of heaven. It is the main source of light, and like the beam of a searchlight it moves around the interior of the building based on the weather and the movement of the sun. There is no covering over the oculus, so when it rains, water enters the dome and is funneled out through drains in the floor.

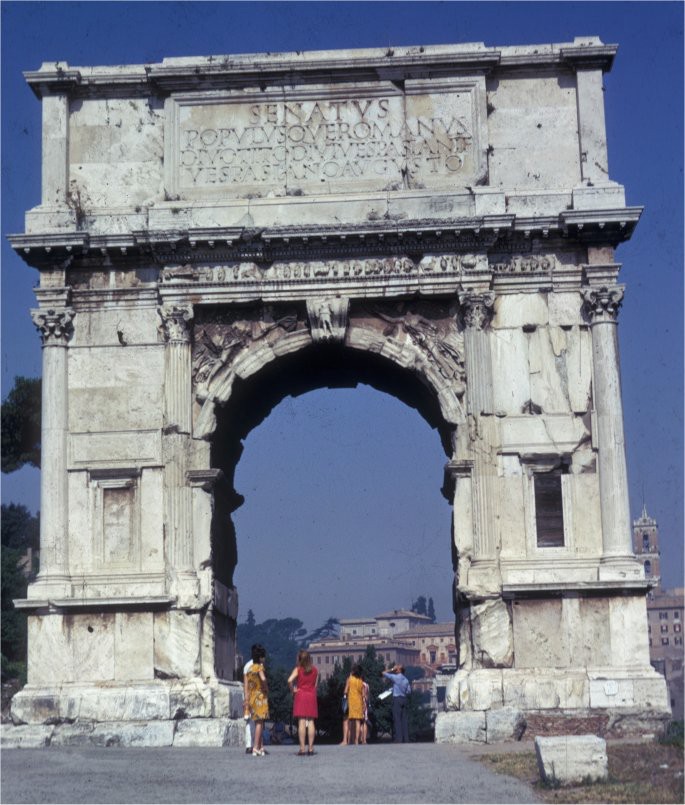

One other common structure seen in Rome and other parts of the Roman Empire was the triumphal arch. It is an ornamental version of a city gate that is moved to the city center to permit processions to enter the forum for celebration. A parade of slaves and booty passed through the arch in tribute to a victorious leader returning from a campaign. The Arch of Titus is an early example of this. It was built to honor Titus when he returned from conquering Jerusalem in 70 CE. There is a memorial inscription in the attic across the top to honor him and his accomplishments. The panels inside of the arch depict the sack of the city and show Roman soldiers carrying away the table of the showbread and the candelabrum from the Holy of Holies in the temple. Other soldiers carry the Arc of the Covenant and Roman military standards.

Roman Philosophy

The philosophies adopted by Rome were as practical as their art and architecture. They focused on two main beliefs: Stoicism, which was founded by the Hellenistic philosopher Zeno of Zitium in 350 BCE, and Epicureanism, founded at about the same time by Epicurus, who was born on the aisle of Samos and studied under Plato. We know that the Romans conquered and absorbed everything Greek, including their art, architectural styles, theater, religious beliefs and their philosophy.

Stoicism was expounded by Epictetus (55-135 CE), a Roman slave. For him philosophy was a way of life. These are some of the basic beliefs of the Stoics:

- Humanity is one people and we are all citizens of one state

- Every person is an actor and the gods assigned the parts

- Humans have a kinship with nature

- Nature is reasonable, so humans should also act reasonably

- Reason is the most divine quality

- Humans can control their own acts

- Do not let anyone gain a hold on you, as this is enslavement

- Life and suffering should be endured with benign resignation

- All experience of evil is to train the mind. Evil is a challenge to exercise our powers of endurance.

- We should deny pain and the pleasures of the flesh

- Adversity produces strength of character Cicero said: Pleasure is the mother of all evils20

Epictetus said: Nature gave us one tongue and two ears so we should hear twice as much as we speak.21

The four Stoic cardinal virtues are:

- Temperance in the sense of sobriety and self-control

- Courage to embrace endurance and fortitude

- Justice meaning to have regard for the rights of others

- Wisdom and practical prudence for all things

Epicurus established a school in Athens, but refrained from civic duty. His most famous work is “On Nature” which was recovered from a charred papyrus in the ruins of Herculaneum. For Epicurus, the man goal in life is happiness, and he bases happiness on our sense of perception.

His basic beliefs include:

- We can become happy by avoiding pain, seeking the greatest pleasure, and practice moderation in all things, since overindulgence can lead to pain

- One man’s pleasure may cause another man’s pain, so avoid hurting others lest there be reprisals and consequent pain to you

- Don’t let today’s pleasure cause tomorrow’s pain

- Eat little to avoid indigestion, drink little to avoid the morning after

- Deny the social responsibility of citizenship

- He encouraged escapism and extreme individualism

Attribution:

Berger, Eugene; Israel, George; Miller, Charlotte; Parkinson, Brian; Reeves, Andrew; and Williams, Nadejda, “World History: Cultures, States, and Societies to 1500” (2016). History Open Textbooks. 2.

References:

1. Photo by Benh LIEU SONG, CC BY-SA 3.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pont_du_Gard_BLS.jpg

2. Photo by Kathleen J. Hartman. CC BY-NC-4.0 License.

3. Photo by Kristine Betts. CC BY-NC-4.0 License.

4. Photo by Kristine Betts. CC BY-NC-4.0 License.

5. Encyclopedia Britannica, 11th edition. Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?search=Plan+of+the+Baths +of+Caracalla&title=Special%3ASearch&go=Go&ns0=1&ns6=1&ns12=1&ns14=1&ns100=1&ns106=1#/media/File:1911_Britannica_-_Baths_-_Baths_of_Caracalla.png

6. German 1891 encyclopedia Joseph Kürschner (editor): “Pierers Konversationslexikon”. Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:CaracallaThermae.jpg

7. Photo by Mats_Haldin. CC BY-SA 3.0 https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Arch_keystones#/media/File:Keystone001.gif viii Photo by Ursus. Public domain.

8. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Basilica_of_Maxentius#/media/File:Roma_Basilica_Maxentius.jpg

9. Photo by Markus Bernet CC BY-SA 2.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Trajan_Forum.jpg

10. Photo by Kristine Betts. CC BY-NC-4.0 License.

11. Photo by Kristine Betts. CC BY-NC-4.0 License.

12. Grisar, Hartman, History of Rome and the Popes in the Middle Ages,1911. In the Public Domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:History_of_Rome_and_the_Popes_in_the_Middle_Ages_(1911)_(147402144 26).jpg

13. Photo by Kristine Betts. CC BY-NC-4.0 License.

14. Photo by Kathleen J. Hartman. CC BY-NC-4.0 License.

15. Stinkzwam at Dutch Wikipedia, Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Piazza_della_Rotonda,_obelisco_macuteo,_e_Pantheon_(Roma_2006).jpg

16. Photo by Yellow.Cat, CC BY 2.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pantheon_dome_-_oculus_light_(5832357251).jpg

17. Photo by Kristine Betts. CC BY-NC-4.0 License.

18. Photo by Hubert Steiner, Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Arc_de_titus_frontal.jpg

19. Photo by Larry from Charlottetown, CC BY 2.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File: Sacking_of_the_ Temple_of_ Jerusalem_ (7966392946).jpg