6.3 ROMAN CIVILIZATION – THE REPUBLIC

From its earliest time, the population of Rome was divided into two orders: the patricians, defined as the descendants from the first one hundred senators appointed to the Roman aristocratic Senate by king Romulus, and the plebeians, that is, everyone who was not a patrician. The plebeians had their own political assembly, the Plebeian Council, while all Roman citizens also belonged to the Centuriate Assembly, which was responsible for annual elections for top political offices. The period of the early Republic, following the expulsion of the kings, was a time of conflict for the two orders, as patricians tried to establish a government that reserved all political power to themselves, whereas the plebeians fought for the opportunity to hold political and religious offices.

Just a decade or so after the expulsion of the kings, shortly after 500 BCE, however, Roman expansion began in earnest.

It is striking to consider that the Romans spent eighty of the hundred years in the third century BCE at war. In 280 – 275 BCE, Rome became embroiled in a war with Pyrrhus, king of Epirus in northern Greece. They defeated Pyrrhus at their third battle against him in 275 BCE, showing the superiority of the new Roman manipular legion even against the phalanx of the Macedonians, military descendants of Alexander the Great. This victory united most of Italy, except for the very northern portion, under Roman rule.

During roughly the same period, from 264 and 146 BCE, the Romans also fought three Punic Wars against Carthage, originally a Phoenician colony that had become a leading maritime power. Rome not only took control of both Carthage and Corinth in 146 BCE, but they plowed the city under and sowed salt in the furrows. The victory over Carthage in the Second Punic War allowed Rome to “close” the circle of the Mediterranean almost completely, acquiring control over all territories that had previously belonged to Carthage. More importantly, the abundance of resources that flowed in following the victories over Carthage raised the question of distribution of this new wealth and land. Starting in 133 BCE, the final century of the Roman Republic was defined by political violence and civil wars.

Increased competition in the late Republic caused three politicians to form alliance in order to help each other. Marcus Licinius Crassus, the wealthiest man in Rome, and Gnaeus Pompey joined forces with a relative newcomer to the world of politics, Gaius Julius Caesar. To cement the alliance, Caesar’s daughter, Julia, married Pompey. Together, they lobbied to help each other rise again to the consulship and achieve desirable military commands.

The alliance paid immediate dividends for Caesar, who was promptly elected consul for 59 BCE and was then awarded Gaul as his province for five years after the consulship. A talented writer as well as skilled general, Caesar made sure to publish an account of his Gallic campaigns in installments during his time in Gaul. As a result, Romans were continually aware of Caesar’s successes, and his popularity actually grew in his absence. His rising popularity was a source of frustration for the other two triumvirs. Finally, the already uneasy alliance disintegrated in 53 BCE. First, Julia died in childbirth, and her baby died with her. In the same year, Crassus was killed at the Battle of Carrhae, fighting the Parthians. With the death of both Julia and Crassus, no links were left connecting Caesar and Pompey; the two former family relations, albeit by marriage, swiftly became official enemies.

Late in 50 BCE, the Senate, under the leadership of Pompey, informed Caesar that his command had expired and demanded that he surrender his army. Caesar, however, refused to return to Rome as a private citizen, demanding to be allowed to stand for the consulship in absentia. When his demands were refused, on January 10th of 49 BCE, Caesar and his army crossed the Rubicon, a river which marked the border of his province. By leaving his province with his army against the wishes of the Senate, Caesar committed an act of treason, as defined in Roman law; the civil war began.

While most of the Senate was on Pompey’s side, Caesar started the war with a distinct advantage: his troops had just spent a larger part of a decade fighting with him in Gaul; many of Pompey’s army, on the other hand, was disorganized. As a result, for much of 49 BCE, Pompey retreated to the south of Italy, with Caesar in pursuit. Finally, in late 48 BCE, the two fought a decisive battle at Pharsalus in northern Greece. There, Caesar’s army managed to defeat Pompey’s much larger forces.

In 44 BCE, having been victorious in the civil war against Pompey and his supporters, Caesar took the title of “dictator for life,” and had coins minted with his image and new title. See image 6.16. His was the first instance in Roman history when a living individual placed his likeness on coinage.

This new title appears to have been the final straw for a group of about sixty senators who feared that Caesar aimed to make himself a king. On the Ides of March (March 15th) of 44 BCE, the conspirators rushed Caesar during a Senate meeting and stabbed him to death. Since Caesar did not have legitimate sons who could inherit— Caesarion, his son with Cleopatra, was illegitimate—he adopted an heir in his will, a common Roman practice. The heir in question was his 19 year old grand- nephew Gaius Octavius, whose name after the adoption became Gaius Julius Caesar Octavianus (or Octavian, in English).

Quickly, he formed an alliance with two experienced former allies of Caesar: Marcus Antonius and Marcus Aemilius Lepidus. The Second Triumvirate defeated Caesar’s assassins at the Battle of Philippi in northern Greece in 42 BCE; they then carved out the Roman world into regions to be ruled by each. Marcus Antonius, who claimed Egypt, although it was not yet a Roman province, proceeded to marry Cleopatra and rule Egypt with her over the following decade. Ultimately, however, another civil war resulted between Antonius and Octavian, with the latter winning a decisive victory in the Battle of Actium in 31 BCE. From that moment until his death in 14 CE, Octavian—soon to be named Augustus in 27 BCE, the name he subsequently used—ruled what henceforth was known as the Roman Empire, and is considered by modern historians of Rome to have been the first emperor.

There are many sculptures of Augustus, but the most famous is the one known as the Augustus Prima Porta which is now housed in the Vatican Museums. The white marble sculpture of Augustus is a copy of the bronze original and was probably carved by Greek sculptors. This work is highly idealized and uses the Polyclitan canon of proportions, so we are fairly certain that he did not actually look like this. It shows him barefooted, as gods are normally barefooted, and his footsteps are guided by Cupid, the son of Venus, riding a dolphin at his feet. This is another reference to his godhood since Augustus said he was related to Venus through his ancestor Aeneas. He wears the leather cuirass, or vest, which depicts both real events and mythological figures, including Tiberius, the son of Livia and Augustus’ successor. It also depicts the god of the sky and the goddess of the earth and images of the enemy Parthian returning military standards that had been taken from Rome in a previous battle. Since Augustus is depicted as a god, the sculpture was probably created after he was deified in 14 CE and before the death of his wife in 29 CE.

While the late Republic was a period of growth for Roman literary arts, with much of the writing done by politicians, the age of Augustus saw an even greater flourishing of Roman literature. This increase was due in large part to Augustus’ own investment in sponsoring prominent poets to write about the greatness of Rome. One of the great poets of the Augustan age was Virgil, who wrote poetry glorifying Augustan Rome. Interestingly, Virgil was probably educated in the classroom of Philodemus, the Greek philosopher whose works have been found in nearby Herculaneum. Virgil’s Aeneid, finished in 19 BCE, aimed to be the Roman national epic and was intended to be the Roman version of Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey combined. It told about the travels of the Trojan prince Aeneas who, by will of the gods, became the founder of Rome. During his travels, before he arrived in Italy, Aeneas was ship-wrecked and landed in Carthage. Dido, the queen of Carthage, fell in love with him and wanted him to stay with her, but the gods ordered Aeneas to sail on to Italy. After Aeneas abandoned her, Dido committed suicide and cursed the future Romans to be at war with her people. Aeneas then went home and fathered a son Ascanius. Image 6.18 shows Aeneas and Ascanius listening to a sow who tells them where to build Rome.

In addition to sponsoring literature, Augustus also focused on building and rebuilding monuments in Rome. In his Res Gestae (The Deeds of the Divine Augustus), which is like an autobiography, Augustus includes a very long list of temples that he had restored or built. Click the link in the endnote to read Augustus’ propagandized list of all he did for Rome.4

Among the new building projects that he undertook to stand as symbols of renewal and prosperity ordained by the gods themselves, none is as famous as the Ara Pacis, or Altar of Peace, in Rome. The altar is dedicated to Pax; a goddess worshipped by Augustus, and was built to celebrate Augustus’ victory in Spain and Gaul. It is about 35’ wide, faced the Pantheon, and was consecrated on the 4th of July 13 BCE. It would have been painted and decorated with gold gilt. The altar features a number of mythological scenes, processions of the gods, and images of the Vestal Virgins; it also integrates scenes of the imperial family, including Augustus himself making a sacrifice to the gods, while flanked by his grandsons Gaius and Lucius. The message of these building projects, as well as the other arts that Augustus sponsored is simple: Augustus wanted to show that his rule was a new Golden Age of Roman history, a time when peace was restored and Rome flourished, truly blessed by the gods.

Pieces of the Ara Pacis were scattered across many museums in Europe, but in 1938, under the watchful eye of Mussolini who was seeking to connect the new German Reich to the glory of ancient Rome, the fragments were brought back together and reassembled. In the early 1990’s an American architectural firm, Richard Meir & Partners built a new enclosure to protect the monument.

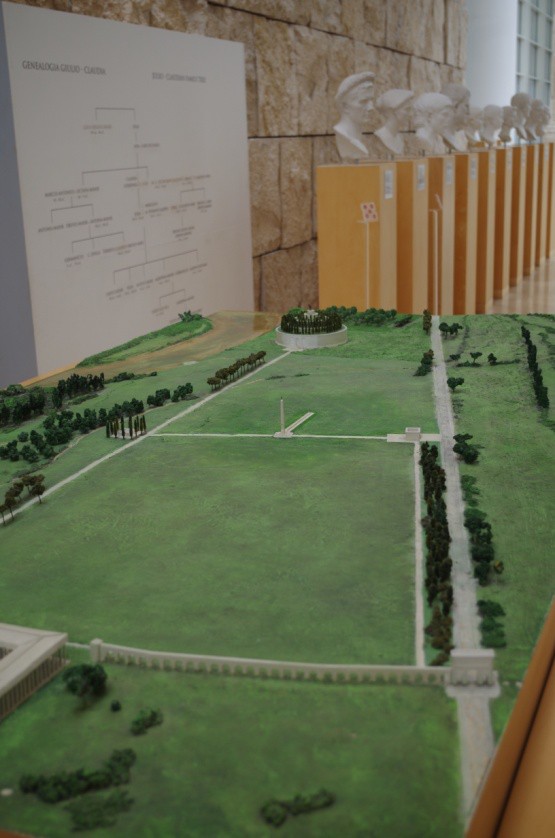

In image 6.21, note the altar in the center of the Campus Martius complex and the Horologium Augusti (sundial) which used an Egyptian obelisk brought from Heliopolis in 10 BCE as the center or gnomon. It is theorized that during the autumnal equinox the shadow of the gnomon pointed to the Ara Pacis and since Augustus was born at that time, it is clearly a reference to him. Augustus would have had to transport the obelisk down the Nile, across the open sea, up the Tiber River, and then through the streets of Rome using ox carts and pulleys until it reached its destination. The Campus Martius was a place for the burial of war heroes and a place for young military recruits to exercise. Romans also came to the site to participate in sporting events. Strabo of Amasia, a Greek geographer, says that Augustus’ ustrinum, which is a repository for his ashes after he was cremated, was also on this campus.8 An abbreviated version of Res Gestae, the list of his buildings and accomplishments, was also written on a slab positioned between two pillars near his burial place in the Campus Martius.

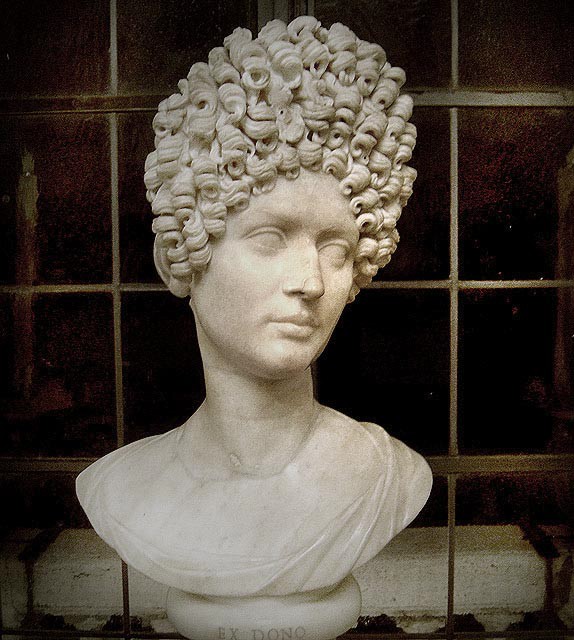

There are many examples of portrait busts that were created during the Republican era. Since many of them do not have any identification directly associated to the work, we cannot always be sure who they are. Keep in mind that Romans were very interested in creating art that was tied to the real rather than the ideal. So much of the art of this period was intended to be portrait art of historical figures, even though we may not always have the correct name of the person it represents. See image 6.22 which are images of unknown Romans. We can assume that these were wealthy persons or someone of political renown because busts were sculpted of them, and this was a time consuming and expensive activity. So they either paid to have it made, or it was made to honor their office and position.

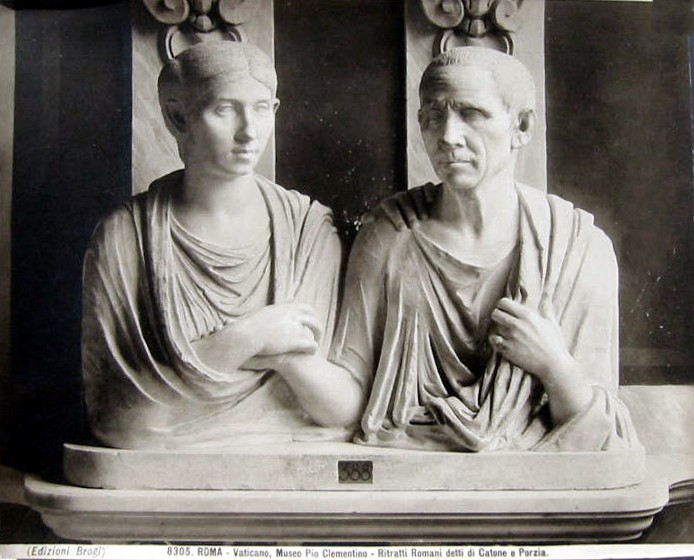

We know image 6.24 is a portrait of Portia and her husband Cato because it is from a headstone, which was installed to encourage reverence and respect for the departed couple who lovingly hold hands.

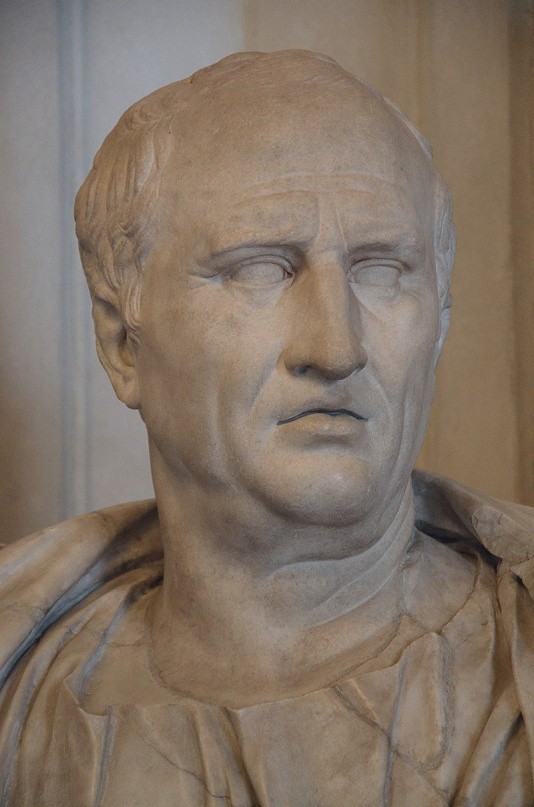

Some portrait sculpture is very well known, like figure 6.25 of Cicero, while other examples of portraits from the Republican era are anonymous and we may not know who they are.

Roman craftsmen were also well known for their beautiful glassware which was used to store and serve food in wealthier Roman homes. They also created the small glass tesserae used to make mosaics and made jewelry and glass sculpture. They created windows to let sunlight into their baths and eventually they were also used to make greenhouses to allow gardens to be kept during colder weather. Glassmakers learned to add a variety of metals to the glass recipe while it heated in the furnace to create different colors of glass. In the first century BCE glassblowing was invented. The craftsman blew air through a pipe into the hot glass and turned it as he blew. This incorporated air into the mixture and formed thinner vessels which were cheaper to make and were available to the lower classes. Roman glassmakers also learned how to add handles, gold leaf, fused ropes of colored glass, and learned to pour glass into molds. See image 6.26 for some examples.

One other type of art we want to mention here is the private living quarters of the very wealthy. The upper class built large, open air homes, called a domus, which included floors covered with mosaics and walls painted with images of nature and the gods and goddesses. The front door to the atrium was open to the street and anyone who had business with the owner was able to enter and wait his turn for an audience. The domus was very different from the insula we discussed in our last chapter. These were places of luxury that housed the well-to-do and their servants.

Attribution:

Berger, Eugene; Israel, George; Miller, Charlotte; Parkinson, Brian; Reeves, Andrew; and Williams, Nadejda, “World History: Cultures, States, and Societies to 1500” (2016). History Open Textbooks. 2.

References:

1. Gallica Digital Library, Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?search=coin+caesar+ dictator&title= Special% 3ASearch&go=Go&ns0=1&ns6=1&ns12=1&ns14=1&ns100=1&ns106=1#/media/File:Cesar_Dictator_Perpetuo_denier_Gallica_23528_ave rs.jpg

2. Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?search=Augustus+Prima+Porta&title=Special:Search&fulltext=1&ns 0=1&ns6=1&ns12=1&ns14=1&ns100=1&ns106=1#/media/File:Statue-Augustus.jpg

3. Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=Special:Search&limit=100&offset=0&profile=default&search= Aeneas+with+Ascanius+&advancedSearch- current={}&ns0=1&ns6=1&ns12=1&ns14 =1&ns100=1&ns106=1# /media/File:Aeneas_ Latium_ BM_GR1927.12-12.1.jpg

4. https://www.livius.org/sources/content/augustus-res-gestae/

5. Photo by Kristine Betts, CC BY-NC-4.0 License.

6. Photo by Luciano Tronati, CC BY-SA 4.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Ara_ Pacis_relief#/media/ File:Ara_ Pacis_ Augustae,_lato_meridionale_06.jpg

7. Photo by Kristine Betts, CC BY-NC-4.0 License.

8. https://www.livius.org/articles/place/rome/rome-photos/rome-mausoleum-of-augustus/

9. Photo by Jason Zhang. CC BY-SA 4.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?sort=relevance&search= Roman+busts&title= Special: Search&profile=advanced&fulltext=1&advancedSearch- current=%7B%7D&ns0=1&ns6=1&ns12=1&ns14=1&ns100=1&ns106=1#/media/File:Royal_Ontario_Museum,_Eato n_Gallery_of_Rome_-_Roman_busts.jpg

10. Photo by Tetraktys, CC BY-SA 3.0. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roman_portraiture#/media/File:Matronalivia2.jpg

11. Photo by Carlo Brogi, Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?search=Portia+and+Cato %2C+ Vatican &title=Special%3ASearch&go= Go&ns0=1&ns6=1&ns12=1&ns14=1&ns100=1&ns106=1#/media/File:Brogi,_Carlo_(1850-1925)_-_n._8305_-_Roma_-_Vaticano_-_Museo_Pio_Clementino_-_Ritratti_romani_detti_di_Catone_e_Porzia.jpg

12. Photo by Carole Raddato, CC BY-SA 2.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?sort=relevance&search=Cicero+Bust&title=Special%3ASearch&profi le=advanced&fulltext=1&advancedSearch- current=%7B%7D&ns0=1&ns6=1&ns12=1&ns14=1&ns100= 1&ns106=1#/media/ File:Bust_of_Cicero,_Capitoline_M useums_(31933016782).jpg

13. By Kathleen J. Hartman , CC BY-NC-4.0 License..

14. By Carole Raddato, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?search=Triclinium %20of% 20villa%20Livia&title=Special%3ASearch&fulltext=1&n s0=1&ns6=1&ns12=1&ns14=1&ns100=1&ns106=1#/media/File:The_Garden_Painting_of_the_Villa_of_Livia_at_Prima_Porta_in_ Rome_(30-20_BC),_detail_with_pine_tree_ and_pomegranate,_ Palazzo_Massimo_ alle_Terme,_Rome_(8534614956).jpg

15. By Carole Raddato, CC BY-SA 2.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=Special:Search&limit= 100&offset=0&ns0=1&ns6= 1&ns12=1&n s14=1&ns100=1&ns106=1&search=Pompeii+atrium&advancedSearch- current={}#/media/File:Atrium_of_ the_House_of_t he_ Menander_(Reg_I),_Pompeii_(14978497650).jpg