1.3 Elements of Art as Demonstrated at the Lascaux Cave Dordogne, France

Paintings are dumb. They don’t say a word. Artists can communicate their beliefs and ideas only by means of carefully chosen basic elements. The relationships of these elements to one another and to the work of art as a whole determine the organization of that work. The Lascaux artists provide clear demonstrations of the formal elements of art, which include:

-

-

-

Line

-

Shape

-

Space, perspective and size

-

Texture

-

Media and tools

-

Color

-

-

LINES are made by the movement of an implement. They give direction and organize the space. There are five kinds of lines: vertical, horizontal, diagonal, curved or straight. Lines may vary in thickness, clarity, smoothness and direction.

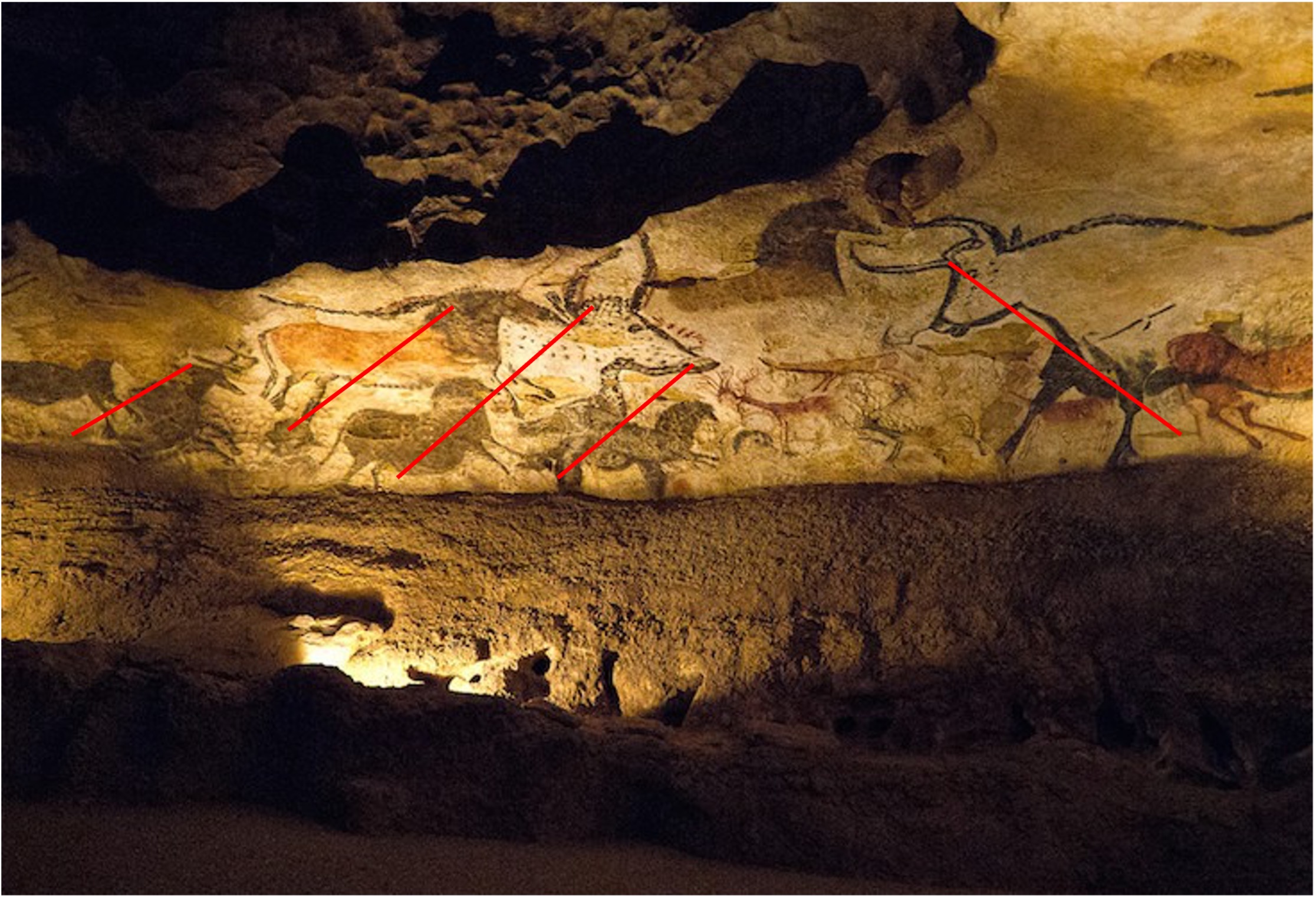

The straight, diagonal and downward slashes in image 1.10 leave no question about the movement of an implement. “Stroke, stroke, stroke.” The rhythm of the lines is even and intentional. The fuzzy lines around the perimeter of the bison suggest texture. By way of contrast, the lines forming the legs and feet are curved, smooth and delicate.

Lines may also be implied, encouraging the viewer to be a participant in the scene. In image 1.11, this author has added red lines to demonstrate the suggestion of forward, confrontational movement.

SHAPES are actual or implied “closed lines.” They must have length and width. Shapes may be regular or irregular, symmetrical or asymmetrical, organic or geometric. Shapes often create a feeling or an emotion.

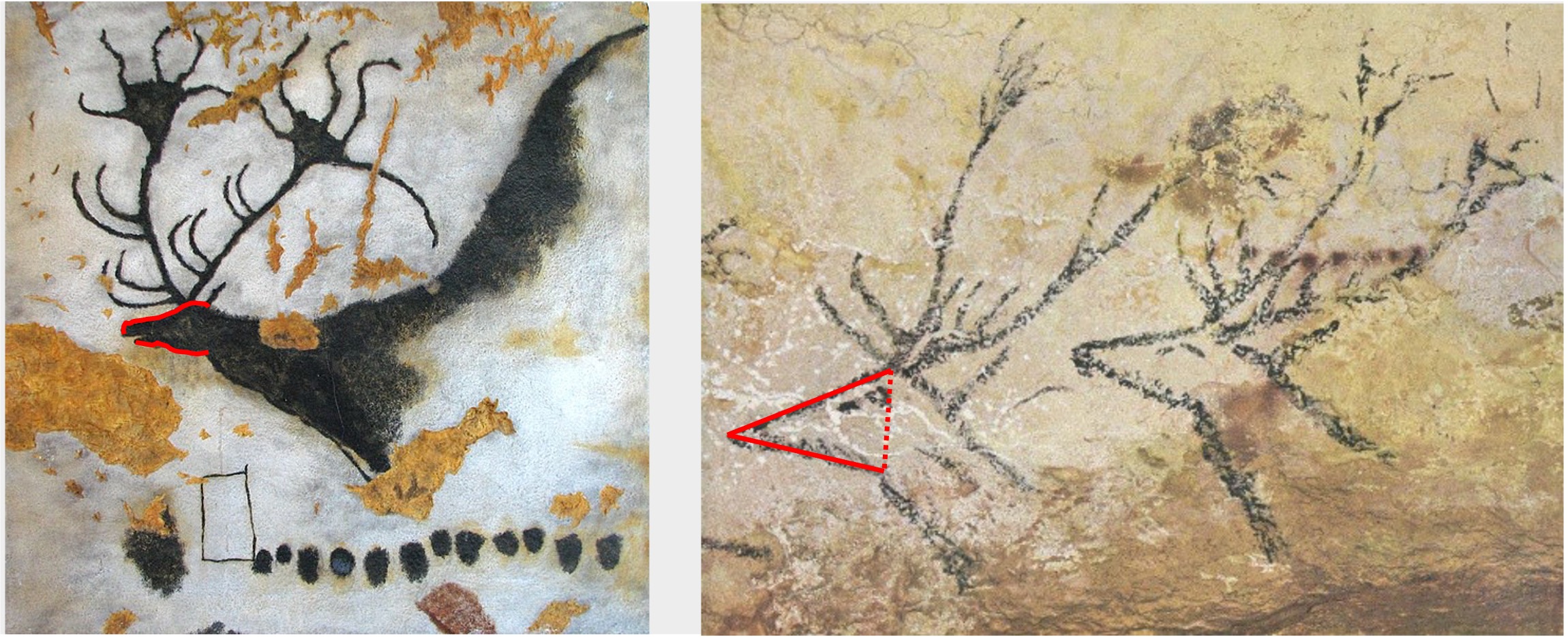

Are the sames of the heads in images 1.12 and 1.13 organic (national forms) or geometric (ideal, abstract forms)? (Red lines have been added by this author.)

Geometric shapes are more popular than one might imagine. Artist Paul Cézanne stated: “All natural forms can be reduced to spheres, cones and cylinders. One must begin with these simple basic elements and then one will be able to make everything one wants.”

SPACE suggests the relationships between shapes (or forms). Space is achieved through size, overlapping, shading and foreshortening of shapes. Perspective is the optical illusion of three-dimensional space on a two-dimensional surface. These techniques add realism to a creation, and may even “fool the eye” (trompe-l’oeil ).

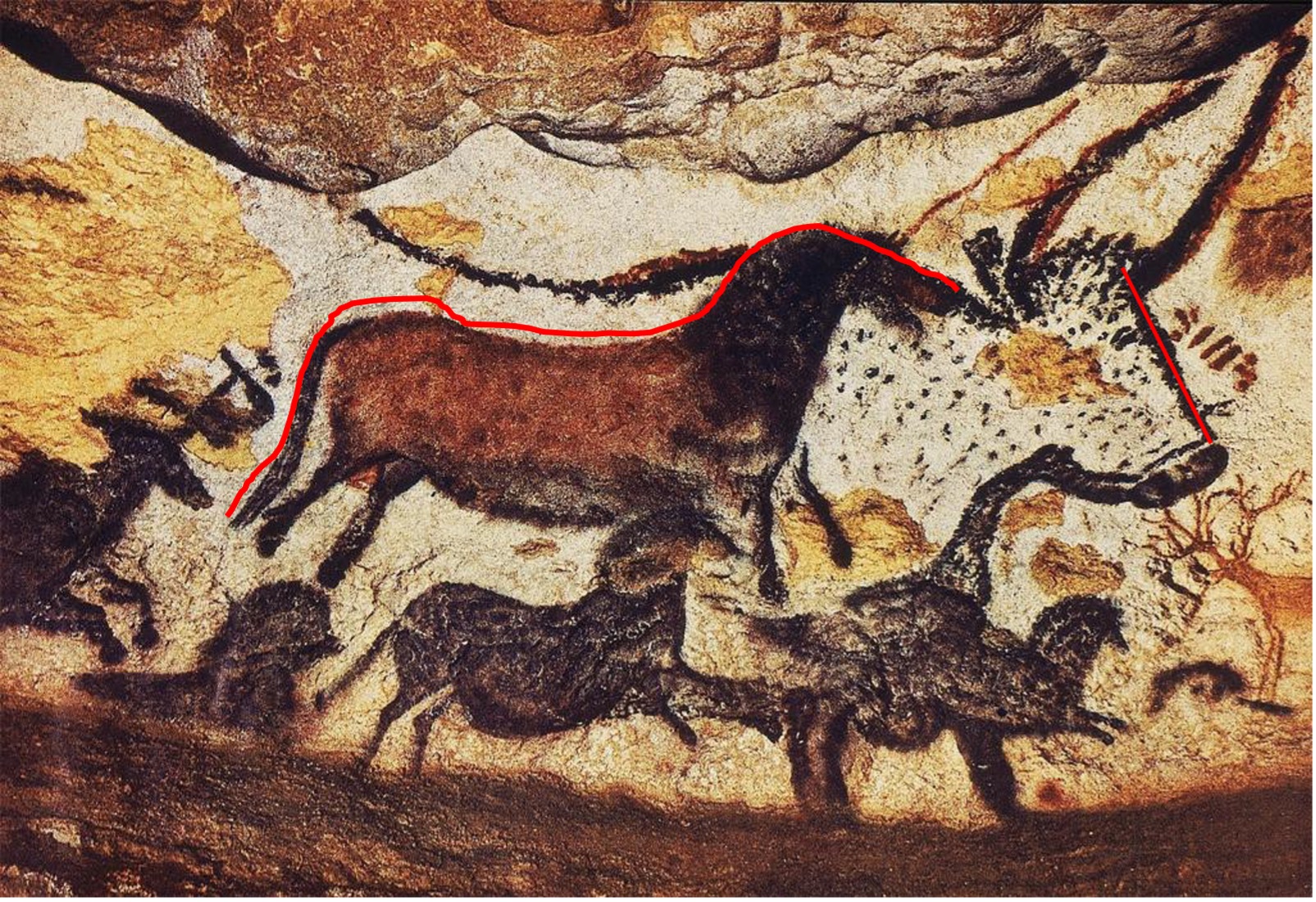

In image 1.14, the bull is shown in profile, but his horns are shown frontally. For your comparison, the drawing [image 1.15] shows a frontal view. This twisted, combined frontal and profile perspective gives the bull more visual power and magical properties.

Yes, SIZE is important in these paintings. The line from the head and rump to the tail of the horse is 11’ 6” long!

Imagine standing on the scaffolding and starting that long line. This artist had a complete vision of the animal. (Certainly the artist at Lascaux had a more steady hand than mine!)

TEXTURE suggests the sensation of touch, such as rough, smooth, wet or even woolly. Without a doubt the texture of the “Little Horse” [image 1.16] is fluffier than the so-called “Chinese Horse” [image 1.17]. The natural relief of the walls may have suggested specific animals, to which the artist may have added actual or implied texture.

All objects have a physical texture. What do you think is the story told by the differing textures of these horses?

An artist must select the MEDIA and TOOLS he or she will use.

- What does the choice of media tell us about these people?

- What tools might they have used?

Tools including lamps, scaffolding and paint “brushes,” were our earliest technology. They were the initial act of extending our control over nature. The remains of oak wood used for scaffolding have been found at Lascaux.

For these paintings, earth pigments were mixed with animal fat. Red came from hematite (iron oxide or red ocher). Black was made from manganese dioxide or charcoal. The white is kaolin or chalk. Minerals were heated to produce yellow, brown, and violet. No green or blue was used in these paintings.

COLOR conveys information and emotion. Color may have a sacred or symbolic function.

(The Yellowstone Bull stepped out in front of my car and declared, “I won’t move until you take my picture!” [image 1.19] Oh! I get the message. It’s spring!! Thanks.)

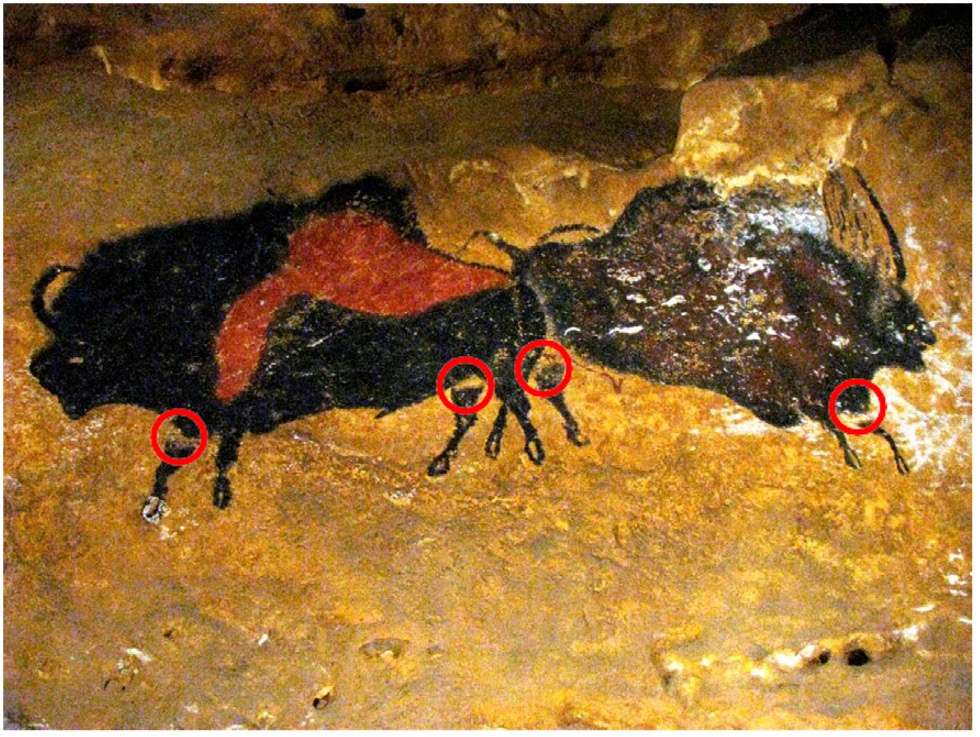

What are the white spaces at the top on the bulls’ legs in image 1.20 all about? (The red circles were added by this author.)

Time-Life photographer Ralph Morse had the unique opportunity to visit the caves shortly after they were opened in 1947. His statement expresses the “WOW” that we feel when we encounter Paleolithic art: “The first sight of those paintings was simply unbelievable. I was amazed at how the colors held up after thousands of years—like they were painted the day before. Most people don’t realize how huge some of the paintings are.”

The last images we will consider are views of the ceiling, first, as it may be seen from inside the cave and secondly, with the view spread out onto a flat surface [images 1.21 and 1.22]. Because you may turn this picture to any direction that pleases you, the depiction also raises questions from several directions:

- What information do the Elements of Art (line, shape, space, texture, media, tools and color) suggest?

- The caves probably benefitted the people for about 5000 years, but people never lived in this cave. Why were these 600 paintings and over 1500 abstract designs created? For art? For religion? For theater? As a teaching tool, a library? An archive of their history?

- Numerically, the most frequently depicted animal was the horse; in lesser numbers there were bison, mammoth, wild goats, wild ox and deer. Lastly, deer! They depended on reindeer for food and materials and yet they are not presented here as the most important creature. What was that all about?

- Some walls were painted over and over again. Why?

- What was so important to these people that they went to such lengths to decorate the cave?

We may consider the Cro-Magnon Homo Sapiens of Lascaux to be primal, but they were not primitive. Anatomically, Paleolithic people were like us with the same clever hands, the same binocular vision and the same integrating brain with powers of abstract thought. As tribal people they lived in small groups of 20-30 people. Men averaged 5’ 8” in height. As hunter-gatherers their survival depended on the animals they could kill and the food they could gather.

Yes, the peoples of the Paleolithic period were remarkable, but the people who came after them, the people of the Neolithic age (starting c. 10,000 BCE), will introduce revolutionary ideas. The domestication of animals and the intentional cultivation of crops with increased tool usage will encourage a transition from food gathering to food producing. The resulting economic benefit will be food that can be shared with others. With the shift from rural/pastoral life toward communal living in cities with an urban/commercial focus the Tigris and Euphrates river valleys as well as the Nile river valley will flourish. In their desire to have some control over this world more energy will be devoted to warfare, religion and the construction of homes, food storage facilities and defensive walls. Both societies will attempt to manipulate nature with irrigation. In both areas, distinctive and differing occupations will evolve, class distinctions will become codified, palaces will be built and, with the advancement of abstract thought, writing will develop to keep track of the whole experience.

References:

1. Christian Jegou Publiphoto Diffusion / Science Photo Library. Property release not required. Accessed from www.sciencephoto.com/contributor/pdx/

2. Accessed from Ministère de la Culture/Centre National de la Préhistoire/Norbert Aujoulat at archeologie.culture.fr/lascaux/en/mediatheque/bison-0

3. Mary Beth Looney, “Hall of Bulls, Lascaux,” in Smarthistory, November 19, 2015, accessed August 16, 2019, smarthistory.org/hall-of- bulls-lascaux/

4. Photo: Don Hitchcock, donsmaps.com

5.Public Domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Swimming_stags.jpg

6. Accessed from Artstor, library.artstor.org/asset/AWSS35953_35953_31673590

7. Public domain at www.freepik.com/free-icon/bull-face-frontal-outline_784099.htm

8. Accessed from Artstor, library-artstor-org.libdb.ppcc.edu/asset/ARTSTOR_103_41822000206142

9. Public domain by the French Ministry of Culture, under the reference PA00082696

10. Accessed from Wikipedia Creative Commons license, photographer Sémhur, 25 September 2009. Source: Original on display at Le Musée National de Préhistoire, Les Eyzies-de-Tayac.

11. Photo by the author, Kathleen J. Hartman, 2010. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

12. Public domain by Don Hitchcock, donsmaps.com, 2008

13. Accessed at www.artstudio.org/houston-museum-of-natural-science-more-than-grafitti/

14. Accessed from Artstor, library-artstor-org.libdb.ppcc.edu/asset/ARTSTOR_103_41822000086999