6.1 Etruscan Influences on Roman Culture

One of the most surprising aspects of the history of early Rome is that, despite constant threats from its more powerful neighbors, it was never swallowed by them. The Etruscans dominated much of northern Italy down to Rome, while the southern half of Italy was so heavily colonized by the Greeks as to earn the nickname “Magna Graecia,” meaning “Great Greece.” Scholars do not agree on the origins of the Etruscans. Some say they came from the east; others say they developed in Italy. The Etruscans became rich through trade with the Celtic world and the Greeks. They are also known to have traded wine and olive oil in what is now France, Switzerland, and Germany. The Etruscans were ruled by the Tarquin kings from about 650 BCE to 500 BCE. During that time they drained the malaria filled marshes, planned and built temples and cities, and constructed roads, which improved relations with the Romans to the south.

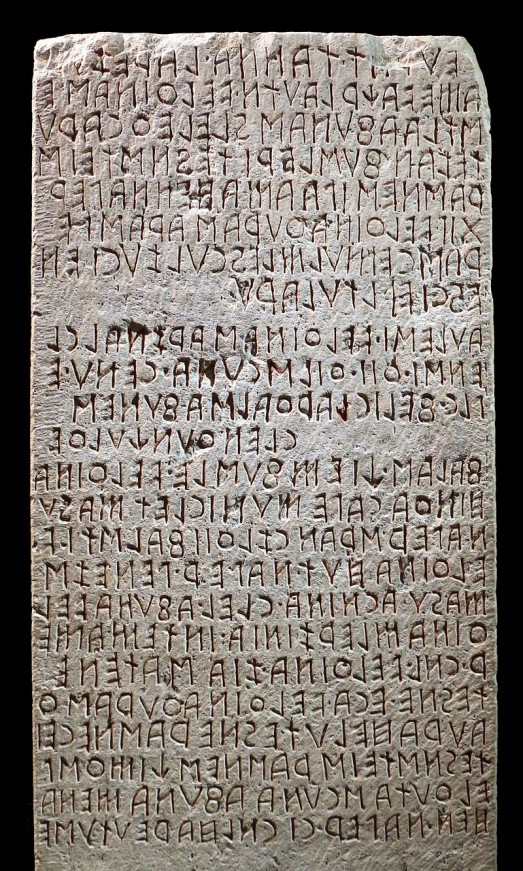

Although there are 10,000 or so inscribed Tuscan texts, there are no known literary works that might tell us about who they are or where they came from. Inscriptions have been found on vases, tombs, statues and jewelry and some of their language was used in religious ceremonies until the 5th century CE.2 To this date scholars are not yet able to translate much of the Etruscan text that has been found, although it is believed that the characters are derived from the Greek alphabet. So the text is not connected to any real literature and does not tell of the origins of their culture. We are left to wonder where they came from and what they believed.

The Etruscans built protected cities atop the hills of what we now call Tuscany. Cività-di-Bagnoregio , see image 6.3, which tourists can now access with a raised walkway, was built in the 12th century atop the ruins of a Roman city, which was built atop an existing Etruscan city. The Etruscans originally chose the site high on a mountain top to provide protection from invaders. Only the columns of the ancient temples remain, and pieces of Civita continue to tumble into the valleys below.

Etruscan men and women enjoyed an active social calendar together. Unlike their Greek counterparts, Etruscan women were given much more freedom to participate in public social events. They were able to obtain an education and to own property. It was not uncommon for women to attend gatherings that might be considered male-only activities in other cultures. We know this because of some of the sarcophagi that have been unearthed. The Sarcophagus of Cerveteri, image 6.4, was created in 520 BCE and was found in the Banditaccia Necropolis, which was an Etruscan city that is now in Rome. In relics of other cultures, women are seen as servants, but in many Etruscan works, husbands and wives lie together on a dining couch, touching and interacting with each other. Their hair, clothing, and facial expressions are stylized, just like the Archaic Greek sculptures of the same period. The eyes are almond shaped and they sit in postures that may not be very comfortable. This work is made of terracotta, most likely because there was no ready source of marble to be found locally. It is 3.7 ft tall by 6.2 ft wide and was made in several sections.

Some of the sarcophagi contain skeletons while others contain ashes, so we believe they used both types of funeral practices. Even though they cremated their dead, they are well known for large temple complexes with elaborately sculpted and painted tombs. Like the Egyptians, they believed in an afterlife. Etruscan tombs are filled with practical grave goods that they believed would be needed for their reunion with family and a continuous series of banquets, games, dancing, wrestling, parades, and music. Tombs looked like homes, and the tomb cities look like cities of the living with streets, parks and plazas.

The Tomb of the Rilievi, image 6.5, is supported by two columns and includes niches along the walls. The walls are covered with painted objects that might have been used by a well-to-do family. There are cooking implements, farm tools, pillows and even pets.The tomb was colorfully painted to enable the inhabitants to feel at home in their eternal environment.

Up until 600 BCE the Etruscans worshipped outdoors in groves beneath the open sky. They then began to build temples to honor their many local gods. Some of these were adopted from the Greek pantheon of gods such as Atumes (Artemis) goddess of the hunt, Nethunes (Poseidon), god of the sea, and Apidu (Apollo). The Apollo of Veii, image 6.6, was positioned on top of the temple of Portonacci with many other Etruscan gods. He is 5’11 inches tall and is made of terracotta. Apollo’s clothing and hair are stylized much like the Greek Archaic works of the same time period. He actively strides forward, moving his arms to keep his balance.

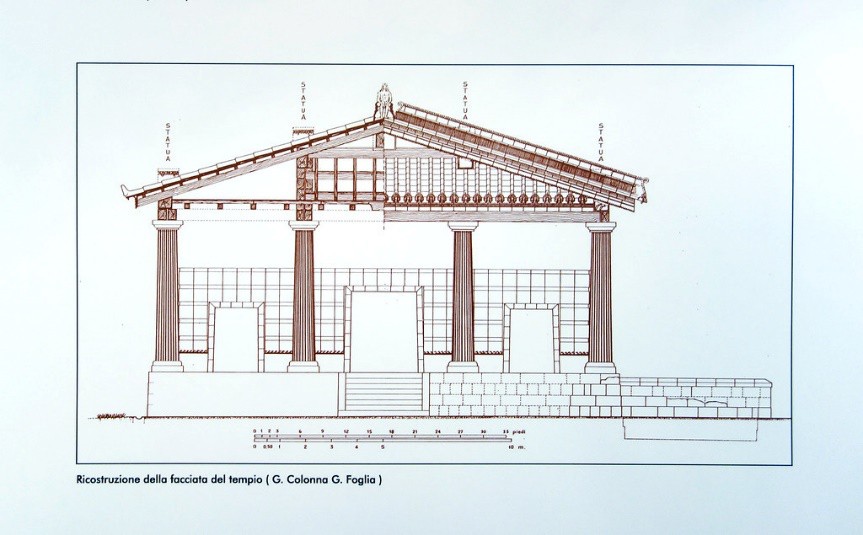

It is believed that many Etruscan gods and their temples were made of perishable materials and have therefore disappeared through the years. Image 6.8 is a reconstruction of the Temple of Veii. Note that is has been built with a deep porch and a large number of Tuscan columns that provide an entrance to three interior rooms or cella. The Etruscans had no marble quarries so their buildings were constructed of individual blocks.

See image 6.7, an Etruscan arch and wall that remain standing. This method was translated by the Romans into the arches and vaults. Note also that statues were intended to be placed on the roof of the building, perhaps in such a way as to tell a story. According to Vitruvius, three doors led into cellas (rooms) for Jupiter, Juno and Minerva.9

The Etruscans were masters of metallurgy. Mars of Todi, image 6.9, is a bronze warrior from the late 5th or early 4th century BCE. It was found on the slope of Mount Santo. It is currently in the Vatican Museum and is a life size, cast bronze sculpture made using the lost wax method. Originally this sculpture included a helmet and probably a spear. Notice the weight shift and the attention to detail in the muscles of the legs and neck. It is likely that the object was dedicated to Laran, the Etruscan god of war. Dressed in intricately worked plate armor, the figure takes a contrapposto stance and indicates that the Etruscan artist was aware of the formal elements of the Classical style of sculpture. It represents the tradition of libations made by soldiers prior to battle, an opportunity to plead with the gods for support and success in battle.

The Etruscans provided a foundational legacy for the Roman Empire. From the Etruscans the Romans learned to use divination to made decisions and establish new towns. They learned to hold elaborate victory processions after battles. They adopted the toga, learned to use currency to purchase goods, and learned to use a dental bridge for their teeth.

Tuscan columns were used in Roman architecture and Etruscan words appear in the Roman language. We know something of the construction of Etruscan temples because of the writings and drawings of Vitruvius in his book “De Architecture” written in the Renaissance. So it would be appropriate to say that it was the Etruscans who provided the foundations of art and architecture used by the Romans and passed down to builders and architects in our time. The Romans copied much from the Etruscan culture, and then they destroyed what was left. It took centuries, but the defeat was total. All we have left of Etruscan culture are a few of their art works, some unconnected inscriptions, and buildings that lay in ruins.

Attribution:

Berger, Eugene; Israel, George; Miller, Charlotte; Parkinson, Brian; Reeves, Andrew; and Williams, Nadejda, “World History: Cultures, States, and Societies to 1500” (2016). History Open Textbooks. 2.

References:

1. Photo by Norman Einstein, CC BY-SA 3.0.https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?search=Etruscan+ civilization+map&title= Special%3ASearch&go=Go&ns0=1&ns6=1&ns12=1&ns14=1&ns100=1&ns106=1#/media/File:Etruscan_civilization_map.png

2. Omniglot.com/writing/Etruscan.

3. Photo by Sailko, CC BY-SA 4.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Etruscan_inscriptions#/media/File:Cippo_perugino_con_iscrizione_in_l ingua_etrusca.jpg

4. Photo by Etnoy, CC BY-SA 3.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Civita_di_Bagnoregio#/media/File:20090414-Civit%C3%A0-di-Bagnoregio.jpg

5. Photo by Gerard M, CC BY-SA 3.0. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sarcophagus_of_the_Spouses#/media/File:Villa_Giulia_-_Sarcofago_degli_sposi.jpg

6. Photo by Roby Ferrari is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tomb_of_the_Reliefs#/media/File: Tomba_ dei_Rilievi_(Banditaccia).jpg

7. Photo by Sailko CC BY-SA 4.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?sort=relevance&search=Veii+apollo&title= Special%3ASearch&profile=a dvanced&fulltext=1&advancedSearch- current=%7B%7D&ns0=1&ns6=1&ns12=1&ns14=1&ns100=1&ns106=1#/media/File:Decorazione_fittile_del_santuario_di_portonaccio,_510-500_ac_ca,_acroteri,_apollo_02.jpg

8. Photo by Kathleen J. Hartman, CC BY-NC-4.0 License.

9. Public domain at https://vvv.khanacademy.org/humanities/ap-art-history/ancient-mediterranean-ap/ap-ancient- etruria/a/temple-of-minerva-and-the-sculpture-of-apollo-veii

10. https://www.ancient.eu/image/6282/etruscan-temple-diagram/

11. Photo by Jean-Pol Grandmont, CC BY-SA 3.0. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Etruscan_civilization#/media/File:0_Mars_de_Todi_-_Museo_Gregoriano_Etruscano_(1).JPG