5.3 Other Sculpture in the Hellenistic Tradition

In addition to the sculpture seen at Pergamon, other Hellenistic sculpture shows an increased use of naturalism. During this time, the rules of Classical art were pushed and abandoned in favor of new themes, genres, drama, and pathos that had never before been explored by Greek artists. A new level of naturalism was added to their figures by adding elasticity to facial and physical forms and expressions. These figures interact with their audience in a new theatrical manner by eliciting an emotional reaction when viewed. This is known as pathos.

NIKE OF SAMOTHRACE

One of the most iconic statues of the period, the Nike of Samothrace, also known as the Winged Victory, (c. 190 BCE) commemorates a naval victory. She is made of Parian marble which is a fine-grained, semi-translucent, pure white, flawless marble quarried during the classical era on the Greek island of Paros in the Aegean Sea. It was highly prized by ancient Greeks. This Parian marble statue depicts Nike, now armless and headless, alighting onto the prow of the ship.

The prow is visible beneath her feet, and the scene is filled with theatricality and naturalism as the statue reacts to her surroundings. Nike’s feet, legs, and body thrust forward in contradiction to her drapery and wings that stream backwards. Her clothing whips around her from the wind and her wings lift upwards. This depiction provides the impression that she has just landed and that this is the precise moment that she is settling onto the ship’s prow. In addition to the sculpting, the figure was most likely set within a fountain, creating a theatrical setting where both the imagery and the auditory effect of the fountain would create a striking image of action and triumph.

VENUS DE MILO

Also known as the Aphrodite of Melos (c. 130-100 BCE), this sculpture by Alexandros of Antioch, is another well- known icon of the Hellenistic period. Today the goddess’s arms are missing, but it has been suggested that one arm clutched at her slipping drapery while the other arm held out an apple, an allusion to the Judgment of Paris and the abduction of Helen. Originally, like all Greek sculptures, the statue would have been painted and adorned with metal jewelry, which is evident from the attachment holes. This image is in some ways similar to Praxiteles’s Late Classical sculpture Aphrodite of Knidos (fourth century BCE) but is considered to be more erotic than its earlier counterpart. For instance, while she is covered below the waist, Aphrodite makes little attempt to cover herself. She appears to be teasing and ignoring her viewer, instead of accosting him and making eye contact.

Notice that unlike Aphrodite of Knidos, this goddess is not successful in keeping her drapery covering herself. A rear view reveals that the drape may be just about to drop off. Although she has the facial expression of a classically calm statue, she is far more sensual than images of women during the Classical age.

ALTERED STATES

While the Nike of Samothrace exudes a sense of drama and the Venus de Milo a new level of feminine sexuality, other Greek sculptors explored new states of being. Instead of, as was favored during the Classical period, reproducing images of the ideal Greek male or female, sculptors began to depict images of the old, tired, sleeping, and drunk—none of which are ideal representations of a man or woman.

The Barberini Faun, also known as the Sleeping Satyr (c. 220 BCE), depicts a reclined figure, a satyr, drunk and passed out on a rock. His body splays across the rock face without regard to modesty. He appears to have fallen to sleep in the midst of a drunken revelry and he sleeps restlessly, his brow is knotted, face worried, and his limbs are tense and stiff.

Unlike earlier depicts of nude men, but in a similar manner to the Venus de Milo, the Barberini Faun seems to exude sexuality.

Above is seen the detail of the faun’s tail. Other than this detail, he is quite human. He dreams and seems about to wake. Again the interest in the moment between waking and sleeping, and life and death, emerges. This was originally cast in bronze, a material that would have been saved for more civic images during the Classical age.

Images of drunkenness were also created of women, which can be seen in a statue attributed to the Hellenistic artist Myron of a drunken beggar woman. This woman sits on the floor with her arms and legs wrapped around a large jug and a hand gripping the jug’s neck. Grape vines decorating the top of the jug make it clear that it holds wine.

The woman’s face, instead of being expressionless, is turned upward and she appears to be calling out, possibly to passersby. Not only is she intoxicated, but she is old: deep wrinkles line her face, her eyes are sunken, and her bones stick out through her skin. Keep in mind that children and old people were not considered ideal enough to depict during the Classical period. During the Hellenistic era, they became quite popular.

All around the Mediterranean and Aegean Seas sculpture reflected the new ideas that were emerging during the Hellenistic age. Pathos replaced ethos in many cases, while in others the ideal was mixed with the real, creating natural, yet theatrical images. These images evoked emotion interacted with their environments and were relatable to the average person.

THE SEATED BOXER

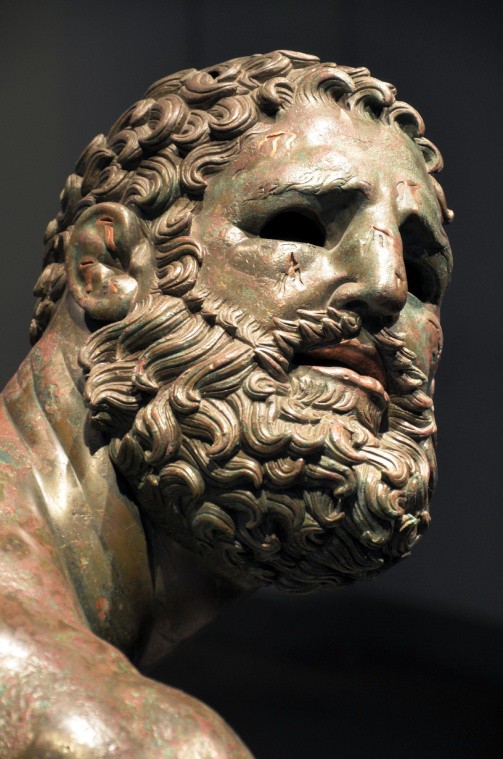

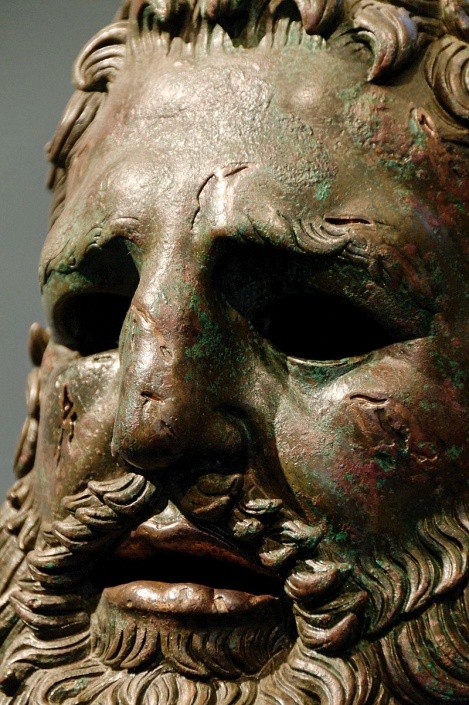

The Seated Boxer by Apollonias, is an excellent example of what can be expected from Hellenistic sculpture. Although the bronze sculpture is from a slightly later time period and is not in motion like many pieces from this era, he fits expectations in many ways. Notice that the boxer is idealistic in his body proportions while he displays the emotion that is associated with realism. Think back to the distinction between realism and idealism as you review this sculpture.

Notice that the figure interacts with his environment. The sculpture is open and invites the viewer into the scene. He turns to the side as if he has just this moment realized that something is there. The shapes are organic. The line of his shoulders defines his slumped body. It is as though he has had a tough bout. Even though he is seated, the contrapposto is extreme.

This sculpture is not about potential. It presents the figure after he has lost. Whereas idealism tends to be seen in sculptures that represent victory over enemies and emotion, this sculpture presents an image of failure. Not only does the boxer seem to have lost his fight, his anguish shows in his facial expression and in the slumped position of his body. The defeated fighter has a swollen ear and a nose that appears to have been broken (indications of realism). Cauliflower ear is a result of multiple trauma to the ear. Note the bend in his nose. Although his muscles are well developed and his hair seems to be perfectly coifed (indications of idealism), he is far from ideal.

The Boxer’s hands are bound in leather. Hands like these had been beating on his face. Greek boxers tended to land blows to the face, rather than to the body. This also explains why his body looks so perfect, even though his face is badly cut and scraped. Note that the boxer displays blood, an illusion created by an inlay of copper in wound areas. Blood, sweat and tears indicate a movement away from idealism.

The Seated boxer, with his deep shadows and bloody hands and face is a great example of the influence that Alexander’s spread of ideas had on sculpture in and after the Hellenistic Age. He is ideal, yet real. He is beaten, human and is interacting with his viewers. He represents changes in Greek identity that were, as they always are, accompanied by changes in art style. He is, in nearly every way, a Hellenistic image.

References:

1. Louvre Museum, Public domain, https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons /e/ee/Nike_ of_Samothrake_ Louvre_ Ma2369_ n2.jpg

2. Livioandronico2013, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Front_view_of_the_Nike_of_Samothrace.jpg

3. Photo by Livioandronico2013, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Front_views_of_the_Venus_de_Milo.jpg

4. Photo by Jastrow, Public domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Venus_de_Milo_Louvre_Ma399_n7.jpg

5. Photo by Vitold Muratov, CC BY_SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Barberini_Faun,_Glyptothek_Munich.jpg

6. Photo by Bibi Saint-Pol, Public domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Barberini _Faun_tail_ Glyptothek_ Munich_ 218.jpg

7. Photo by Shakko, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Barberini_Faun_ (casting_in_Pushkin_museum)_ by_ shakko_03.jpg

8. Photo by Tetraktys, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bebada2.jpg

9. Photo by Carole Raddato, CC BY-SA 2.0 https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/3/3f/ Boxer_of_Quirinal%2C_ Greek_ Hellenistic_bronze_sculpture_of_a_sitting_nude_boxer_at_rest%2C_10050_BC%2C_Palazzo_Massimo_alle_Terme%2C_Rome_%2813332767605%29.jpg

10. Photo by Marie-Lan Nguyen, CC By 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Thermae_boxer_Massimo_Inv1055_n5.jpg

11. Photo by Marie-Lan Nguyen, CC By 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Thermae_boxer_Massimo_Inv1055_n9.jpg

12. Photo by Marie-Lan Nguyen, CC BY 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Thermae_boxer_Massimo_Inv1055_n7.jpg

13. Photo by Marie-Lan Nguyen, CC BY 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Thermae_boxer_Massimo_Inv1055_n10.jpg