5.1 Introduction to the Hellenistic Tradition

The Peloponnesian War from 431 to 404 BCE rocked the Greek world. The end of that war was, for nearly everyone involved, disastrous. However, the intellectual and artistic legacy of Greece continued to gain popularity and would influence a new, short-lived Empire and the Romans that would shortly overtake and develop most of it. Although Sparta ended the War allied with Persia, their former enemy, the population had been decimated by the long period of fighting. There had always been a much larger number of slaves, the Helots, than there were masters in the Peloponnese. Sparta became dependant on the slaves they had captured centuries earlier. With the Spartan numbers decreased it took about a half century before the Helots won their freedom, putting an end to the power the Spartans had won in the war.

In 146 BCE, the Romans took over the area and the Spartans became Roman. Athens and her allies suffered worse. Athens lost her navy and she would never again rise to the level of power that she had enjoyed before the war. Although the Democracy was briefly restored, it did not last, nor did the oligarchy that briefly ruled. The power vacuum was filled in 338 BCE when Phillip the king of Macedonia defeated Athens and several of her allies. Phillip was from an area mostly known for people who had the audacity to drink undiluted wine. Literacy was low and the king himself did not read or write. He quickly adapted to Athenian ways, however, and was at the marriage of his daughter to another ruler, when he was assassinated.

One of the legacies that Phillip left was the combining of religious and political power. This idea was probably borrowed from Persia, a country that had been successful with that approach to rule.

Phillip was replaced by his son Alexander in 336 BCE when he was 16 years old. Up to that time Alexander had been tutored by Aristotle. Alexander inherited a strong kingdom and an experienced army. In his youth he had been awarded the generalship of Greece, and used this authority to launch his father’s military expansion plans.

In 334 BCE, he invaded the Achaemenid Empire, ruled Asia Minor, and began a series of campaigns that lasted ten years.

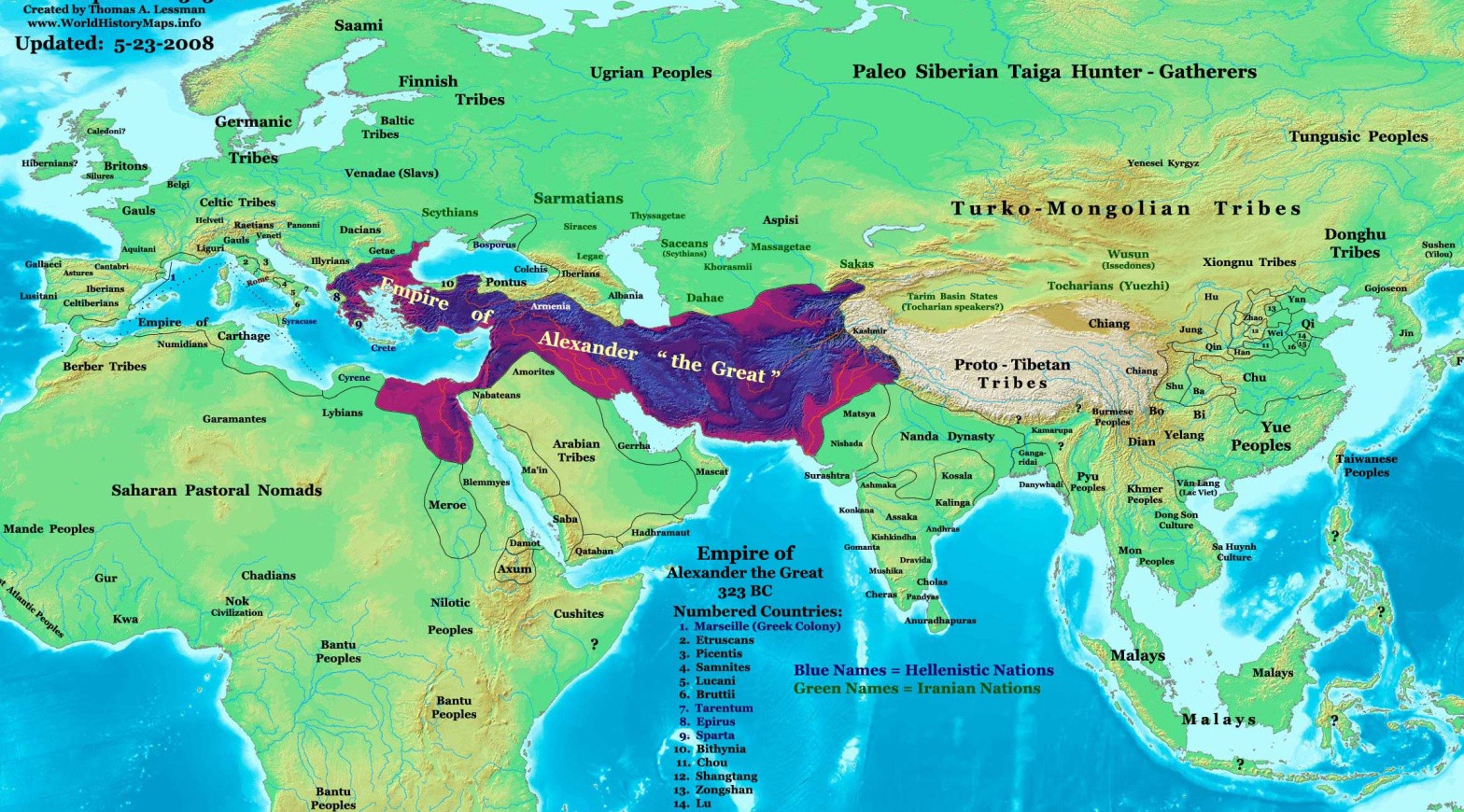

Alexander broke the power of Persia in a series of decisive battles, most notably the battles of Issus and Gaugamela. He overthrew the Persian King Darius III, and conquered the entirety of the Persian Empire. At that point, his empire stretched from the Adriatic Sea to the Indus River. Planning to reach the “ends of the world and the Great Outer Sea,” he invaded India in 326 BCE, but was eventually forced to turn back at the demand of his troops. Alexander died in Babylon in 323 BCE, the city he planned to establish as his capital, without executing a series of planned campaigns that would have begun with an invasion of Arabia. In the years following his death, a series of civil wars tore his empire apart, resulting in several states ruled by the Diadochi, Alexander’s surviving generals and heirs.

Alexander’s legacy includes the cultural diffusion brought by his conquests. He founded some 20 cities that bore his name, the most notable being Alexandria in Egypt. Alexander’s settlement of Greek colonists, and the spread of Greek culture in the east, resulted in a new Hellenistic civilization, aspects of which were still evident in the traditions of the Byzantine Empire in the mid-15th century. Alexander became legendary as a classical hero in the mold of Achilles, and he features prominently in the history and myth of Greek and non Greek cultures. He became the ruler against which military leaders measured themselves. Military academies throughout the world still teach his tactics.

Alexander’s ideas spread throughout the known world and lasted much longer than his Empire. His son was too young to take over upon his death and so his generals fought each other over who should rule, effectively disempowering and dismantling the Empire. Partly due to the competing ideas of Aristotle and Plato, and partly due to the many cultures that became Hellenized with the movement of Alexander’s army, there existed multiple artistic styles and philosophical influences. As complex as this seems, by tracking those cultural influences and the ideas of those two philosophers, sense can be made of the confusion.

ARISTOTLE VERSUS PLATO AND OTHER ODDITIES

One of the most distinctive aspects of the Hellenistic tradition is syncretism, the mixing of cultural elements, styles, values, religious ideas etc. This was also common during the early Archaic period. Another critical element was the spread of the ideas of Aristotle and Plato. Thirdly, the rise of personal art altered the style considerably, while monumental art grew bigger and more impressive. These elements combined to define a new era. For a review of the major differences between the ideas of Aristotle and those of Plato, see the chart below:

| Criteria | Aristotle | Plato |

| Highest Good: | Happiness | Knowledge |

| Cultural Values: | Empiricism

Individualism Antiquarianism |

Rationalism

Humanism Idealism |

Empiricism, discovering truth through the senses, is in direct conflict with Plato’s idea that truth must be reached through application of pure reason, which is rationalism. Remember that in the Athenian court system of the Classical age, eye- witness testimony and physical evidence were not trusted and as such, reason was the only defense. It was also the only way to convict a suspect.

Once the Democracy and many Republics had fallen, many people turned to their own lives in hope of finding truth.

Individuals no longer had power over their political lives and so, instead of focusing on the betterment of the whole, people often turned to the betterment of themselves, focusing on the individual, rather than the group.

This is also the time that Antiquarianism began to develop. Alexander spent much of his short life going from oracle to oracle to prove to himself and others that he descended from divinity. This combination of politics and religion, adopted by his father, would continue to develop into propaganda that supported his rule and later the rule of Rome. As this idea developed, the idealism seen in many sculptures of the time was not actually intended as a cultural value that was being sought after, but as a tool to influence people.

Because of these seemingly conflicted values and because of the many cultures that were merging ideas, there was an interesting mix of art styles that could be seen around the Mediterranean Sea and the Aegean Sea. Below is a chart of what to keep an eye out for in your study of the Hellenistic Tradition. Personal art had become more common during the Late Classical Period, and it continued to grow in popularity. Monumental art, sponsored by the ruling powers, also continued to develop. Although the two types of art shared many things, stylistically, there are some ideas that tended to appear more often in one or the other.

| Personal Art | Personal and Monumental Art | Monumental Art |

| Novelty | A mix of idealistic and realistic styling | Deified ruler |

| Exoticism | A mix of cultural stylistic elements | Monumental tombs |

| Human | Intense feeling of movement | Idealism as propaganda |

| Virtuosity | Non frontal | Victory monuments |

| Speculation | Deep Shadows | Colossal Statues |

| Images of loss | Viewed from all angles |

The tetradrachm above provides an excellent example of the deification of rule, as well as providing an example of syncretism. Alexander was smart. He put an idealized image of himself in the hands of all of his subjects. Here he appears wearing the crown of rule and symbols of religion that both his new subjects and his Greek subjects would recognize. The head of Alexander is featured wearing royal and divine symbols: the diadem and the horns of Zeus Ammon. Ammon is a Libyan deity that Alexander consulted at an oracle in the desert. This use of propaganda would influence many generations to come. Image 5.4 shows Alexander with more than a passing resemblance to Apollo. This was not an accident.

Clues when Comparing Greek Art

- Geometric Art: Frontal, closed space, full sun half god perfection of the artistic type

- Classical Art: General idea of a marshal warrior, god-like man rising above limitations

- Hellenistic Art: Non-frontal, deep shadow, open space, organic shapes, half-brute, defeat of the human spirit, sometimes a bit shocking

- Idealism: Ethos, self-control, order, denial of change

- Realism: Pathos, passion, suffering discontent, embraces change, emotions

Watch for these ideas as you investigate Hellenistic art and architecture from 323 to 146 BCE. Of course there will be exceptions to the rules but this will help you to grasp how Hellenistic art is distinctive. One of the important results of this combining of cultures and values will be new philosophy that develops from the syncretism. Those philosophical viewpoints, Stoicism and Epicureanism will be discussed further in Chapter 6, Roman Philosophy. Another important idea that will continue to influence politics is the Antiquarian tendency to deify, or to find divine origins for the rulers.

Attributions:

Boundless World History I: Ancient Civilizations –Enlightenment. “Ancient Greek and Hellenistic World, Macedonian Conquest.” Boundless Resources.com

References:

1. Photo by Andrew Dunn, CC BY-SA, https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/a/a1/AlexanderTheGreat_Bust_Transparent.png

2. Map by Thomas Lessman (Contact!), CC BY-SA, https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/6/6a/Alexander-Empire_323bc.jpg

3. Photo by Mike Peel (www.mikepeel.net), CC BY-SA 4.0, https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/9/99/Alexander_coin%2C_British_Museum.jpg

4. Photo by Yair Haklai, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/8/88/Alexander_the_Great- Ny_Carlsberg_Glyptotek.jpg