3.2 Egypt-Old Kingdom

In the Old Kingdom pharaohs built pyramids to emphasize their relationship to the divine and facilitate their ascent to the gods after their earthly deaths. Pyramids probably contained tombs for the pharaohs and their wives, but the wealth within the burial site was so tempting, that grave robbers made quick work of emptying the tombs and selling the contents. The earliest pyramids were built in stair-step layers. Some scholars believe they represent creation stories in which a mound of dry land appeared out of the marsh of the Nile. The stone steps enabled the pharaoh to ascend to the sun after his death. See Image 3.9.1

Pyramids were marvels of engineering, built on a massive scale to honor the pharaohs and usher them into the afterlife. Egyptian pyramid builders adhered to several rules:

- Pyramids were built on the West side of the Nile, where sunset represented death, and the dead were also generally buried on the western side of the river.

- Each side of the pyramid faced one of the cardinal directions. (N,S,E,W)

- Pyramids were constructed near enough so that the Nile could be used as a source of transportation for the huge building blocks. Care was taken to select a site without cracks in the bedrock to ensure stability.

Tombs were never again as grandiose as they were in the Old Kingdom, partly because of the persistence of the grave robbers. Since no intact Royal tombs from this era have yet been found, and it’s hard to imagine what they must have been like. Pharaohs were mummified to preserve their bodies and were buried with everything considered necessary for the afterlife, including furniture, jewelry, makeup, pottery, food, wine, clothing, and sometimes even pets. The most recognizable pyramids from the Old Kingdom are the three pyramids at the Giza complex, which were built for a father and his son and grandson, who all ruled during the fourth dynasty. See image 3.10.

The pyramids of Giza were built for a Father, Khufu (Greek, Cheops, ca. 2530 BCE), Son Khafre (Greek Chephren, ca. 2500 BCE), and Grandson, Menkaure (Greek Mycerinus, ca. 2470 BCE). See Image 3.10. The largest Pyramid known as the Great Pyramid of Giza, is still largely intact today. It was the largest building in the world until the Eiffel Tower was built in 1888. Over 449 feet high, it covered an area of 13 acres and was built with over 600 tons of limestone. The sides are each 755’ with a variance from the longest to the shortest sides of between 2” and 7”, depending on who is measuring. It is within 1/20 of a degree of true North. Skilled craftsmen and local labor forces of Egyptians were the primary builders of the pyramids. The Great Pyramid of Giza took an estimated 20 years to construct and employed skilled stonemasons, architects, artists, and craftsmen, in addition to the thousands of unskilled laborers who did the heavy moving and lifting. Each side of the pyramid faced one of the cardinal directions. The construction of these pyramids was an enormous, expensive feat.

They stand as testimony to the increased social differentiation, the great power and wealth of the Egyptian pharaohs and the significance of beliefs in the afterlife during the Old Kingdom.

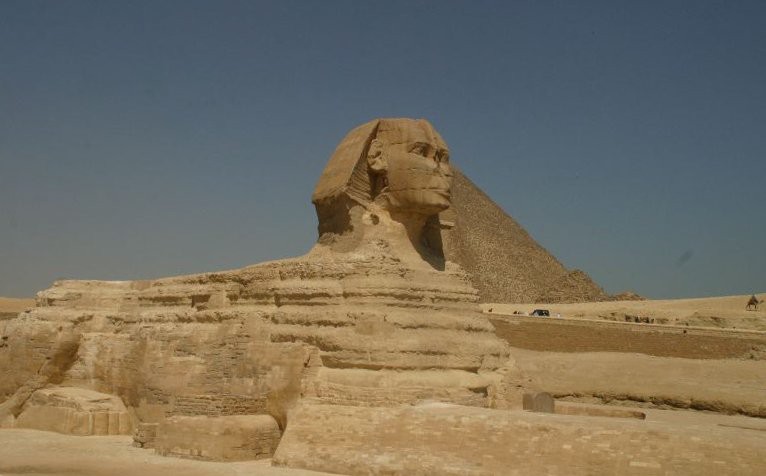

Huge funerary monuments were intended to guarantee immortality. One example is the Sphinx at Giza which was built in about 2540 to 2514 BCE near the pyramids. The human head represents the pharaoh with the body of a lion and is 240 feet long and 65 feet high.

King Chefren, also known as Khafre is depicted in this a dark green diorite sculpture. See Images 3.12 and 3.13. His proportions and clothing are realistic, but this was not intended to be a portrait. Instead it represents the divinity of the king. So it would be more correct to describe it as an idealized version of Chefren. Note that the king is calm and confident in his power, and Horus, the falcon god sits on his shoulder protecting him from danger and validating his right to rule.

Refer back to the introductory section about Palette of Narmer to see the canon of rules. Note how they apply here: The king is idealized and consorts with the gods. He stands moving powerfully forward. This work was intended to be seen only from the front, so the back is flat and not carved. No effort was made to remove the excess stone. Royal sculpture was carved of hard stone like diorite or schist so as to last for millennia and represent the king for eternity. Keep in mind, however, that this king lived 4400 years ago, and it is possible that only the works of art made of hard materials have survived the centuries. There may have been many other beautiful works of art made of less durable materials that did not survive.

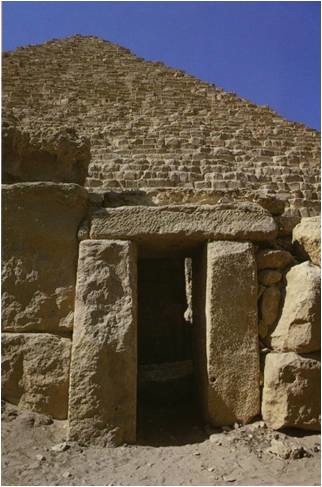

This sculpture, Image 3.14, shows Menkaure and is probably his Queen Kha-merer-nebty II, although no names were included on the work itself. It is about 4’7” tall and is carved and polished from greywacke. He wears the ceremonial beard, headdress, and kilt of the pharaoh and is depicted as a young, vigorous man. The queen wears a thin sheath which is visible near her ankles and which clings to her, emphasizing her feminine characteristics and therefore her fertility. The lower portions of his kilt and their legs and feet are not polished as are the upper portions of their bodies. His left foot is slightly forward of his right. There are traces of paint on this sculpture, indicating that it was originally painted. The entrance to Menkaure’s mortuary temple, Image 3.15, is an excellent example of the post-and-lintel construction method. Notice that the weight of the lintel is held up by the two massive posts on either side of the door. We see this type of construction in temples and tombs all over Egypt.

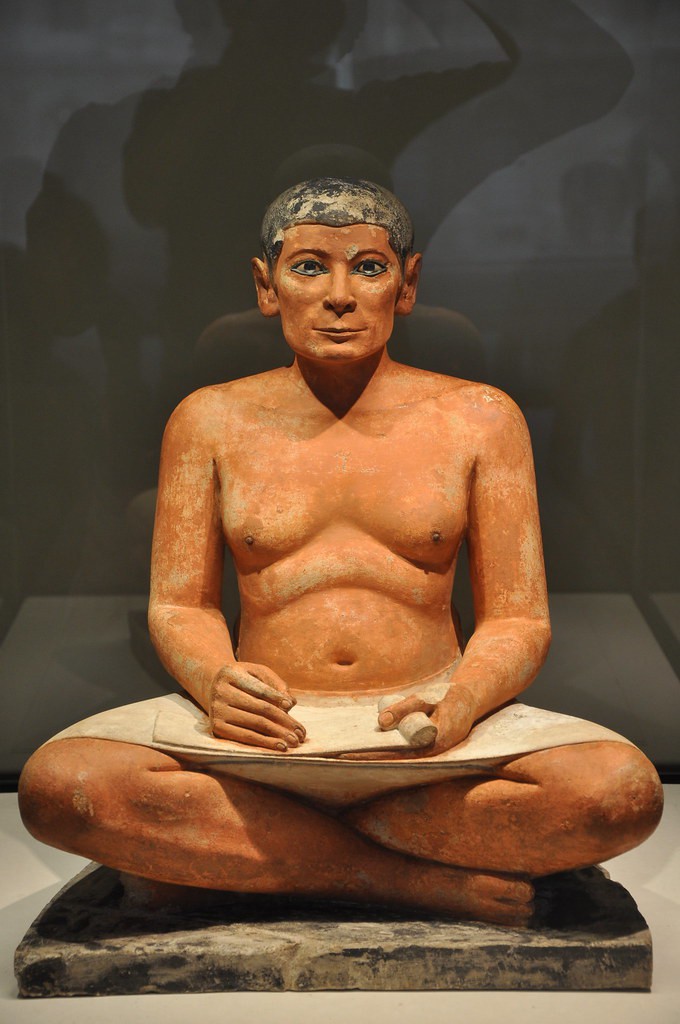

The Seated Scribe, Images 3.16 and 3.17, is made of painted limestone, and shows a more natural man than the ideal pharaoh. His features could depict the man as he was, with a square jaw and normal belly fat. The scribe was the most educated person in the king’s court. He could read and write and probably knew some math and some aspects of the law. Although most scribes were men, there is some evidence that wealthy women also might have learned to read and write.

Other important people also had funerary sculpture created for their tombs. Rahotep, see Image 3.18, was the High Priest, adviser to and military commander of Pharaoh Sneferu. Rahotep and his wife Nofret commissioned these seated sculptures of themselves of carved limestone about 2600 BCE. Notice that Nofret has a little extra weight in her neck and chin, which is normal. Both husband and wife hold their hands in ceremonial positions, and there are hieroglyphics painted behind them on the plinth. Note the color of their skin is the common red for a man who worked and conducted his business outside and white for a woman, who kept the house and children indoors and stayed away from the sun most of the day.

In addition to the construction of pyramids, the Old Kingdom saw increased trade and remained a relatively peaceful period. The pharaoh’s government controlled trade. Egypt exported grain and gold and imported timber, spices, ivory, and other luxury goods. During the Old Kingdom, Egypt did not have a standing army and faced few foreign military threats. Lasting almost 400 years, the Old Kingdom saw the extension of the pharaoh’s power, especially through the government’s ability to harness labor and control trade. However, the power of the pharaohs began to wane in the fifth dynasty of the Old Kingdom. Continuing environmental change that led to droughts and famine, coupled with the huge expense of building pyramids likely impoverished pharaohs in the last centuries of the Old Kingdom.

Attribution:

Berger, Eugene; Israel, George; Miller, Charlotte; Parkinson, Brian; Reeves, Andrew; and Williams, Nadejda, “World History: Cultures, States, and Societies to 1500” (2016). History Open Textbooks. 2.

References:

1. https://www.sacred-texts.com/egy/pyt/pyt12.htm

2. By Arian Zwegers, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?sort=relevance&search=File%3AStepped+Pyramid+of+Djoser+at+Saqqar a.jpg&title=Special%3ASearch&profile=advanced&fulltext=1&advancedSearch- current=%7B%7D&ns0=1&ns6=1&ns12=1&ns14=1&ns100=1&ns106=1#/media/File:Saqqara,_step_pyramid_of_Djoser(6201557496).jpg

3. Samehm1998, CC BY-SA 4.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?search=Pyramids%20of%20Giza&title=Special%3ASearch&fulltext=1&ns0=1&ns6=1& ns12=1&ns14=1&ns100=1&ns106=1#/media/File:Giza_Pyramids_-%D8%A3%D9%87%D8%B1%D8%A7%D9%85%D8%A7%D8%AA_%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AC%D9%8A%D8%B2%D8%A9.png

4. By Nina Aldin Thune, CC BY-SA 3.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?search=Sphinx%20of%20Giza&title=Special%3ASearch&fulltext=1&ns0= 1&ns6=1&ns12=1&ns14=1&ns100=1&ns106=1#/media/File:Sphinx_Giza.jpg

5. Photo by Kathleen J. Hartman, CC BY-NC-4.0 License.

6. Soutekh67, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Statue_of_Khafra_protected_by_Horus#/media/File:Khephren+Horus.j pg

7. Photo by Kathleen J. Hartman, CC BY-NC-4.0 License.

8. Photo by Kathleen J. Hartman, CC BY-NC-4.0 License.

9. By RAMA CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 France. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_seated_scribe-E_3023-IMG_4267- gradient.jpg

10. Photo by Kathleen J. Hartman, CC BY-NC-4.0 License.

11. By Roland Unger CC BY-SA 3.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?search=Rahotep%20and%20Nofret&title=Special%3ASearch&fulltext=1 &ns0=1&ns6=1&ns12=1&ns14=1&ns100=1&ns106=1#/media/File:CairoMuseumRahotepNofret.jpg