4.10 The Buildings on the Acropolis

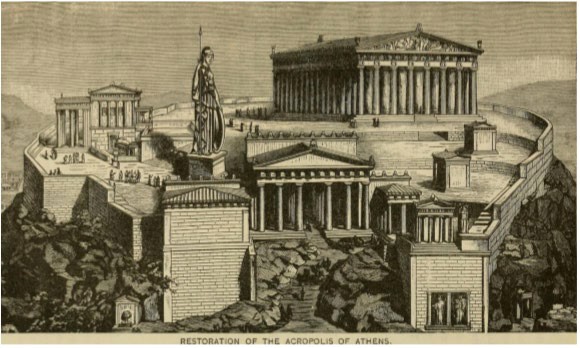

By around 500 BCE ‘rule by the people,’ or democracy, had emerged in the city of Athens. Following the defeat of a Persian invasion in 480-479 BCE, mainland Greece and Athens in particular entered into a golden age. In drama and philosophy, literature, art and architecture Athens was second to none. The city’s influence stretched from the western Mediterranean to the Black Sea, creating enormous wealth. This paid for one of the biggest public building projects ever seen in Greece, which included The Parthenon.

The temple known as The Parthenon, was built on the Acropolis at Athens between 447 and 438 BCE. It was part of a vast building program masterminded by the Athenian statesman Pericles. Within the interior of the temple, which is executed in the Ionian style, stood a colossal statue representing Athena, patron goddess of the city. The statue, which no longer exists, was made of gold and ivory and was the work of the celebrated sculptor, Phidias.

The Parthenon would become the largest Greek Doric temple, although it was innovative in that it mixed the two architectural styles of Doric and the newer Ionic. The temple measured 101’4” by 228’ and was constructed using a 4:9 ratio in several aspects. The diameter of the columns in relation to the space between columns, the height of the building in relation to its width, and the width of the inner cella in relation to its length are all 4:9.1

Be sure to view this short video. You will learn more about the great temple of Athena, patron of Athens, its corrections of optical illusions and the building’s troubled history: Khan Academy VIDEO: Parthenon (acropolis) from Smarthistory (16:04).2

If you have trouble viewing the video above, use this link: https://smarthistory.org/the-parthenon-athens/.

Parthenon Sculptures

The Parthenon was decorated with marble sculptures representing scenes from Athenian cult and mythology. There are three categories of architectural sculpture. The interior, ionic frieze, carved in low relief, ran high up around all four sides of the building inside the colonnades. The metopes, carved in high relief, were placed at the same level as the frieze above the architrave surmounting the columns on the outside of the temple. The exterior of the building is constructed in the Doric style. The pediment sculptures, carved in the round, filled the triangular gables at each end.

The Parthenon served as a church until the fifteenth century, when the Ottoman Turks conquered Athens, and the building became a mosque. In 1687, during the Venetian siege of the Acropolis, the defending Turks were using the Parthenon to store for gunpowder, which was ignited by the Venetian bombardment. The explosion blew out the heart of the building, destroying the roof and parts of the walls and the colonnade.

The Venetians succeeded in capturing the Acropolis, but held it for less than a year. Further damage was done in an attempt to remove sculptures from the west pediment, when the lifting tackle broke and the sculptures fell and were smashed. Many of the sculptures that were destroyed in 1687, are now known only from drawings made in 1674, by an artist probably to be identified as Jacques Carrey.

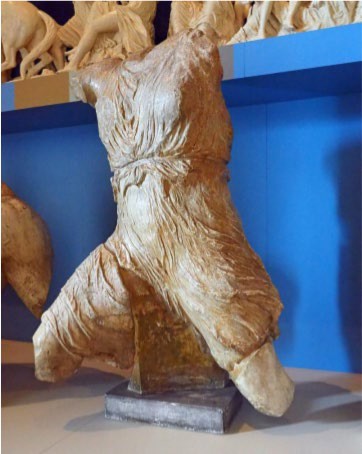

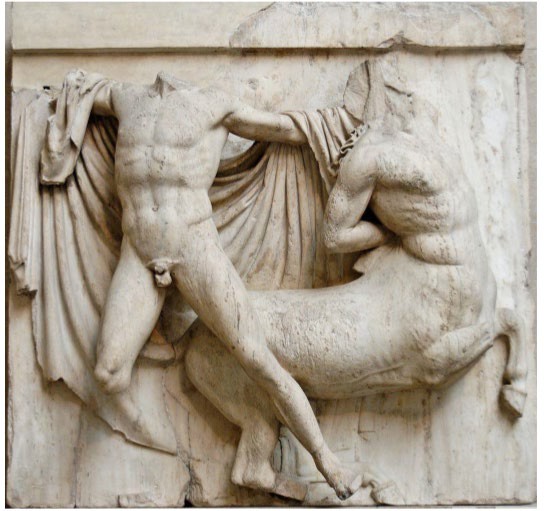

Here a young Lapith holds a Centaur from behind with one hand, while preparing to deliver a blow with the other. The composition is perfectly balanced, with the protagonists pulling in opposite directions around a central space filled by the cascading folds of the Lapith’s cloak. The sculpted decoration of the Parthenon included ninety-two metopes showing scenes of a mythical battle. Those on the south flank of the temple included a series featuring human Lapiths in mortal combat with Centaurs. The Centaurs were part-man and part-horse, thus having a civil and a savage side to their nature.

The Lapiths, a neighboring Greek tribe, made the mistake of giving the Centaurs wine at the marriage feast of their king, Peirithoos. The Centaurs attempted to rape the women, with their leader Eurytion trying to carry off the bride. A general battle ensued, with the Lapiths finally victorious. This imagery served as a fitting metaphor for the Athenian Democracies’ defeat of the beastly, enslaved Persians. Democratic Athenians considered anyone who served a king to be enslaved. Other races were generally depicted as more animal-like than the highly civilized Athenians.

This block was placed near the corner of the west frieze of the Parthenon, where it turned onto the north. The horsemen have been moving at some speed, but are now reining back so as not to appear to ride off the edge of the frieze. The horseman in front twists around to look back at his companion, and raises a hand (now missing) to his head. This gesture, repeated elsewhere in the frieze, is perhaps a signal. Although mounted riders can be seen here, much of the west frieze features horsemen getting ready for the cavalcade proper, shown on the long north and south sides of the temple. The east pediment of the Parthenon showed the birth of goddess Athena from the head of her father Zeus. The sculptures that represented the actual scene are lost. Zeus was probably shown seated, while Athena was striding away from him fully grown and armed.

View the video at the following link for an in-depth look at the Parthenon sculptures:7

Khan Academy clip from Smarthistory, Phidias, Parthenon sculpture (pediments, metopes and frieze) (14:25).

Phidias, Parthenon sculpture (pediments, metopes and frieze)

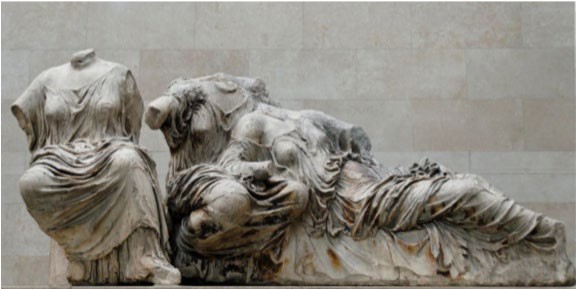

Only some of the figures ranged on either side of the lost central group survive. They include these three goddesses, who were seated to the right of center. From left to right their posture varies in order to accommodate the slope of the pediment that originally framed them. They are remarkable for their naturalistic rendering of anatomy blended with a harmonious representation of complex draperies.

The incorporation of multiple styles does not diminish the importance of proportionate ratios that are seen in both architecture and sculpture of the Classical age. These ideas reflect the Greek interest in the application of reason and enhance the superiority that Athenians seemed to feel was a part of their legacy. In spite of the mixture of styles, allies were often unimpressed. Many felt that the use of Delian League funds and the arrogance of the Athenians presenting themselves in friezes with the gods was too much. Including styles popular in regions other than Athens was not enough to stem the anger of many allies who felt that the Parthenon was a symbol of betrayal.

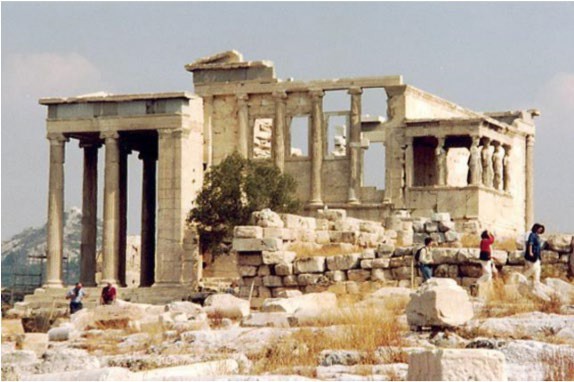

THE ERECHTHEUM

Another temple on the Acropolis is the Erechtheum. This temple is essentially built in the ionic style but the design is unusual in that it is not a symmetrical structure. Sitting at the edge of the cliff atop the Athenian Acropolis, it incorporates the foundation of an Archaic temple and honors the site where Athena was deemed the patron of the city of Athens, which is named for her. Here the olive tree is visible that now stands where the mythical tree grew when Athena struck the ground with her spear. It also houses an area dedicated to Zeus and another that is dedicated to Poseidon. This building is smaller and more elegant than its neighbor, the Parthenon. It exemplifies Athenian ingenuity in its somewhat unusual construction.

The Erechtheum was finished decades after the larger temple, which was completed in 432 BCE. shortly after the beginning of the Peloponnesian War. The Erechtheum was completed 26 years later, shortly before the end of that long war. Take a closer look at this multi-level, multi-purpose structure by viewing the video at the following link:

“The Erechtheion” (8:08)

If you cannot view the video above, use this link https://smarthistory.org/the-erechtheion/.

Looking up at the north porch, one can see the coffers that decorated the ceiling and reduced the weight of the roof. Just behind the left center column, the hole is visible that marks the spot through which Poseidon thrust his trident to land below, creating a salt spring. Below the hole in the ceiling is a hole in the floor that allows viewers to see where the trident struck the ground.

The Erechtheum is perhaps the most complex building on the Acropolis. It houses shrines to several different deities, including Athena, Zeus and Poseidon. It is named for the mythic King Erechtheus who judged the contest between Athena and Poseidon for who would be the patron deity of Athens.

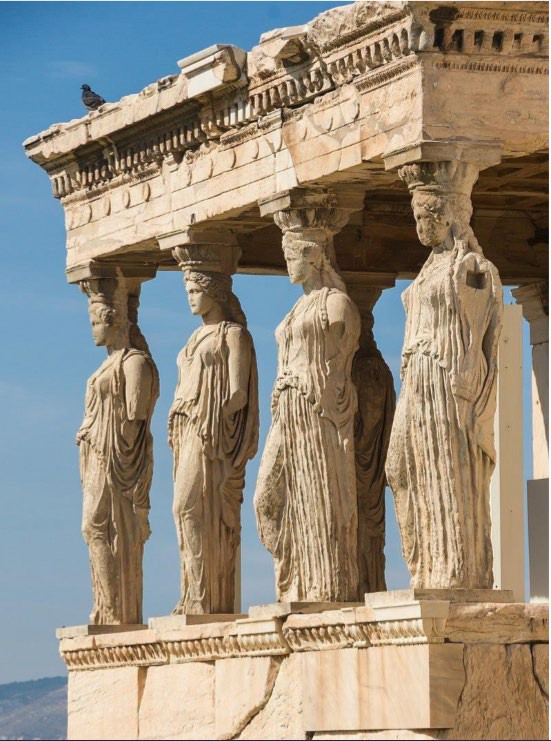

This caryatid is one of six elegant female figures that support the roof of the south porch of The Erechtheum (figures who do the work of columns—carrying a roof—are called caryatids). The figure wears a garment pinned on the shoulders (this is a peplos, a kind of garment worn by women in ancient Greece). The drapery bunches up at the waist and pours over the belt. She stands in contrapposto with her left knee bent and pressing against the drapery. The folds of drapery on the right side resemble the fluting (vertical grooves) on a column. She looks noble and calm despite the fact that she carries the weight of a roof on her head.

These graceful female figures replace columns. Think about how the human form and architecture relate in ancient Greece. Keep in mind that both sculpture and architecture were based on ideal mathematical proportions. Although the arms have broken off, it is likely that the figures once held offerings, probably to the gods being honored in this temple. It is most likely that the arms bent at the elbow and the hands held out those offerings. Note that the figures are fully carved in the round. Also notice that the figures are each slightly different but that the legs that are nearest the sides of the porch are the more column-like, creating a symmetrical grouping.

The Erechtheum is a highly decorated and elegant Ionic temple. The scroll forms at the top of the column which is called the capital, and its tall slender profile indicate that this is the Ionic order. The column is formed of four pieces, known as drums, and is fluted (decorated with vertical grooves). Just below the scroll shapes, also called volutes, there are decorative moldings. Also note the decoration on the entablature below. The entablature is the horizontal area carried by the column. It is called “egg and dart” (egg shapes alternating with V- shapes), and below that there is a ring of plant-like shapes—an alternating palmette and lotus pattern.

In its complexity, the Erechtheum represents Athenian piety and ingenuity. It is a temple to Zeus, Poseidon and Athena. It honors an ancient temple, whose foundation supports it. It honors the legendary king of Athens, Erechtheus, in its name and location and it straddles the cliff and creatively employs its own version of symmetry. The Erechtheum is truly a monument to Athenian ambition, idealism, history and religion.

THE TEMPLE OF ATHENA NIKE

The smallest building on the Athenian acropolis is the Temple of Athena Nike. Nike is a reference to victory and as such, this temple celebrates Athena as a protector of the city. The building was constructed to house the ancient wooden statue of Athena that was believed to have dropped from the sky and that was rescued when Athens abandoned the acropolis to the Persian army. Like the Parthenon and the Erechtheum this temple is unique. It is placed at the southwest corner, at the edge of a high cliff. Its construction was completed in the year 420 BCE during the High Classical Period. It was built according to the design of Kallikrates, the same architect who was responsible for the construction of the Parthenon. The temple by Kallikrates replaced an earlier small temple, which was completely destroyed during the Persian wars.

The spot, highly vulnerable to attack but also well placed for defense, was appropriate for the worship of the goddess of victory. There is some archaeological evidence that the location was used for religious rituals already in Mycenaean age, roughly from 1600 to 1100 BCE. Mycenaeans also raised the first defensive bastion here and its fragments are preserved in the temple’s basement.

The temple of Athena Nike, built in the Ionic order using beautiful white Pentelic marble, has columns at the front and back but not on the sides of the cella; this kind of floor plan is called an amphiprostyle. Because of the small size of the structure, there are only four columns on each side. The columns are monolithic, which means that each one of them was made of a single block of stone, instead of horizontal drums, as it was in the case of the Parthenon.

Another interesting detail is that the columns of the temple of Athena Nike are not as slender as those of many other Ionic buildings. Usually the proportion between the width and the height of an Ionic column was 1:9 or even 1:11. Here the proportion is 1:7—and the reason for that choice might have been the intention to create a harmonious whole with other buildings nearby. The temple of Athena Nike stands just next to the Propylaea, a heavy, monumental gateway to the Acropolis, built in the Doric order. To visually counteract this massive structure, the architect may have decided to widen the columns, otherwise the building might feel out of place and be too delicate in contrast to the neighboring architectural mass of the Propylaea. The ancient Greeks were very aware of mathematical ratios while constructing architecture or creating statues, feeling that the key to beauty lay in correct proportion.

As with all Greek temples, the Temple of Athena Nike was considered a home of the deity as represented in its statue, and was not a place where regular people would enter. The believers would simply perform rituals in front of the temple, where a small altar was placed, and they could glimpse the sculpted figure of the goddess through the spaces between the columns. The privilege of entering the temple was reserved for the priestesses, who held a respected position in Greek society. As the name suggests, the temple housed the statue of Athena Nike, a symbol of victory. It probably had a connection to the victory of the Greeks against the Persians half a century earlier. Nike usually had wings, but in this case we know that the statue had no wings, hence it was called Athena Apteros, which means without wings. The ancient Greek writer Pausanias later explained that the statue of Athena had no wings so that she could never leave Athens.

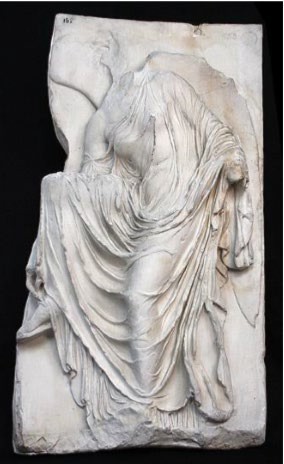

This temple featured beautiful sculptural decoration, including a typical continuous Ionic frieze on the eastern side that represented a gathering of gods. On the southern wall, the sculptor showed a battle between Greeks and Persians, and on the remaining sides, battles between Greeks and other warriors. Sculptures on the pediments, almost entirely lost, most probably depicted the Gigantomachy, a story of Zeus fighting the Titans, and Amazonomachy, a story of the Amazons. Best known are reliefs from the outside of the stone parapet that surrounded the temple at the cliff’s edge. These represented Nike in different poses and could be admired by people climbing the stairs to the Acropolis. Most famous of these is the Nike Adjusting Her Sandal. It presents the goddess in a simple, everyday gesture, perhaps adjusting her sandal, or maybe taking it off, as she prepares to enter the sacred precinct. Whatever she is doing, the relief is still charming in its elegance and simplicity. Both Nike Adjusting Her Sandal and parts of the frieze can be admired today at the Acropolis Museum.

Attributions:

CARYATID AND COLUMN FROM THE ERECHTHEION (https://smarthistory.org/caryatid-and-ionic-column-from-the-erechtheion/)

The British Museum, “The Parthenon, Athens,” in Smarthistory, December 14, 2015, accessed July 30, 2019,

https://smarthistory.org/the-parthenon-athens/. And, Dr. Jeffrey A. Becker, “Greek architectural orders,” in Smarthistory, August 8, 2015, accessed December 26, 2019, https://smarthistory.org/greek-architectural-orders/.

Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker, “Caryatid and Ionic Column from the Erechtheion,” in Smarthistory, November 25, 2015, accessed August 2, 2019,

Katarzyna Minollari, “Temple of Athena Nike on the Athenian Acropolis,” in Smarthistory, September 11, 2016, accessed January 2, 2020.

References:

1. Cartwright, Mark. “Parthenon.” Ancient History Encyclopedia. Ancient History Encyclopedia, 28 Oct 2012. Web. 26 Dec 2019.

2. Video, (Iktinos and Kallikrates (sculptural program directed by Phidias), Parthenon, Athens, 447 – 432 BCE. Speakers: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker.) found on The British Museum, “The Parthenon, Athens,” , December 14, 2015, accessed December 26, 2019.

3. CC BY 3.0 https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?sort=relevance&search=parthenon+frieze&title=Special:Search&pr ofile=advanced&fulltext=1&advancedSearch- current=%7B% 7D&ns0= 1&ns6= 1&ns12= 1&ns14= 1&ns100=1&ns106=1#/media/File:Parthenon_frieze_w_facade_ in_situ.jpg

4. https://smarthistory.org/the-parthenon-athens/ https://search.creativecommons.org/photos/7b3d371d- 3cad-46fe-9892- 416533617710

5. Photo by Marie-Lan Nguyen (User:Jastrow), 2007 CC BY 2.5 https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?search=Metope+parthenon&title=Special%3ASearch&go=Go&ns0=1&ns6=1&ns12=1&ns14=1&ns100=1&ns106=1#/media/File:South_metope_27_Parthenon_BM.jpg

6. Cavalry from the Parthenon Frieze, West II, 2–3, British Museum Public Domain https://en.wikipedia.org /wiki /Parthenon_Frieze# /media/File: Cavalcade_ west_frieze_Parthenon_BM.jpg

7. Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker, “Phidias, Parthenon sculpture (pediments, metopes and frieze),” in Smarthistory, November 25, 2015, accessed August 1, 2019, https://smarthistory.org/parthenon-frieze/.

8. © Marie-Lan Nguyen CC BY 2.5 https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?sort=relevance&search= Parthenon+sculpture+pediment&title=Special: Search&profile=advanced&fulltext=1&advancedSearch- current=%7B%7D&ns0=1&ns6=1&ns12=1&ns14=1&ns100=1&ns106=1#/media/File:East_pediment_KLM_Parthenon_ BM.jpg

9. © Marie-Lan Nguyen CC BY 2.5 https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?sort=relevance &search= Parthenon+sculpture+pediment&title=Special: Search&profile=advanced&fulltext=1&advancedSearch- current=%7B%7D&ns0=1&ns6=1&ns12=1&ns14=1&ns100=1&ns106=1#/media/File:East_pediment_KLM_Parthenon_ BM.jpg

10. Photo by Stan Shebs is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File: Erechtheum_ SW-650px.jpg

11. Photo by Юкатан is liscensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/8/8e/Coffered_ceiling_of_Erechtheum.jpg

12. Photo by Psy guy is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File: Column_rom_ Porch_of_the_Caryatids.JPG

13. Photo by Jebulon, CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication. https://commons.wikimedia.org/ wiki/File: Four_Caryatids_erechtheum_Acropolis_Athens.jpg

14. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

15. Photo by Jebulon, CC0 1.0, Public Domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki /File:Detail_ Erechtheum_ Acropolis_Athens.jpg

16. Photo by George E. Koronaios, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons /4/47/ The_ Temple_of_Athena_Nike_on_the_Acropolis_of_Athens .jpg

17. Restoration of the Athenian acropolis. Internet Archive Book Images [No restrictions] https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/0/0b/A_general_history_for_colleges_and_high_schools_%28188 9%29_%2814578006309%29.jpg

18. Temple of Athena Nike detail. Benjamín Núñez González [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by- sa/4.0)] https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/4/4f/Templo_de_Atenea_Nike%2C_Atenas%2C_Grecia%2C_2019 _02.jpg

19. Université Bordeaux Montaigne [Public domain] https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons /b/b6/ Moulage_du_temple_d%27Ath%C3%A9na_Nik%C3%A9%2C_Ath%C3%A8nes%2C_relief_du_parapet_Nik%C3%A9_d%C3%A9tachant_sa_sandale_avant_d%27entrer_dans_le_sa nctuaire%22.jpg