4.8 Later Development of the Archaic Kouros 600 to 480 BCE

As new ideas arrived in mainland Greece, the residents began to develop an identity based on how they fit into the world around them. Early in the period, as was seen in the “Early Archaic” section, influences from Egypt and other areas meshed with the earlier geometric style to spark development of a new style. This new style became more and more natural as time moved forward and the burgeoning Northern Greek identity continued to develop.

Each city-state had its individual founding story tied to a mythological figure. Through shared language, religion, lifestyle, and trade, the development of the northern sculptural style was shared throughout the area. Most of the statues were created as votives or grave markers, replacing the kraters and amphorae of the earlier period. Other than small personal items, such as perfume bottles and mirrors made from polished metal, these are the artworks most associated with individuals.

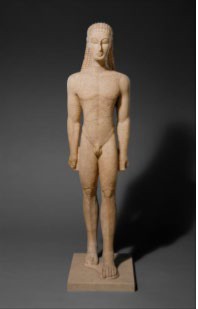

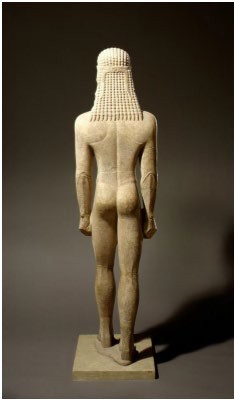

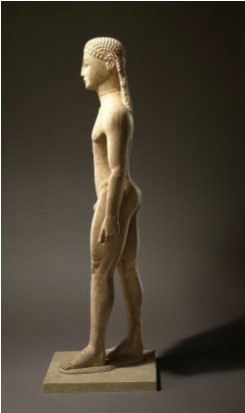

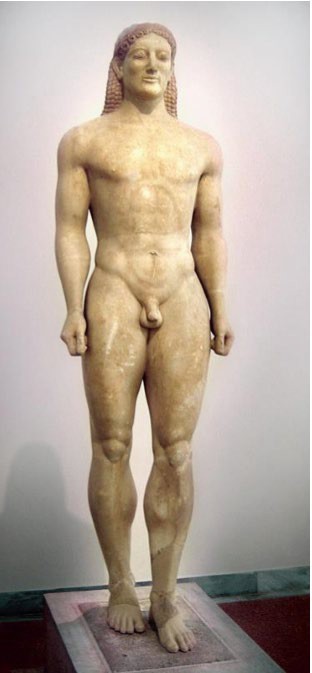

Kourai (pronounced kuer-eye) was the term applied to sculptures of nude males. Each one of these was referred to as a kouros (kuer-ose). These sculptures resemble Egyptian sculpture in many ways. They are stepping forward on flat feet. They have idealized bodies and their stance is fairly stiff. They are facing straight forward in the direction that their feet are pointed. The early kourai are nearly expressionless like their Egyptian cousins. Although Hatshepsut is female, the Egyptian statue is so idealized (The ideal ruler was the ideal male) that her gender is hard to identify. The kouros is also an image of the ideal male.

They were not, however, entirely Egyptian in style and the differences became more pronounced as the style developed. The Greek figures have a smile on their lips, whereas the expressions on the Egyptian statues are always unemotional. The Greek figures are freestanding. The space between their legs is not filled with stone as they are in monumental Egyptian carvings. Instead, the legs of the kouros support the weight of the sculpture. The Greek male statues are not clothed as Egyptian male statues are. These sculptures have elements of earlier sculpture. There are geometric looking lines incised into the surface of the torso, but they now indicate musculature.

Although these images make it appear as though the Greeks loved unpainted marble, they would have been brightly painted, as all sculptures were during the Archaic and Classical Periods. The hair, headband, eyes, lips and the neckpiece would all have been painted. Because ancient painters had not yet discovered strong binders, only small deposits of the paint remain. In order to appreciate it, it must be investigated through a microscope and chemical testing.

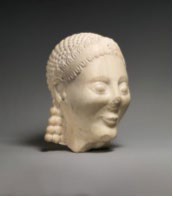

The next image is a close-up view of the head of the New York Kouros. The eyes seem to lie on top of the surface of the face, rather than being recessed into the skull, as eyes naturally are. The head is smaller than is often seen in Geometric sculpture but the proportions are still not natural. Note that the back of the head is reduced so much that the ear is quite close to the where the occipital bone would be. The ear is also stylized. It seems to be constructed of a geometric spiral.

The highly stylized hair, held back by a headband seems more Egyptian than Greek. Note the change in expression, below, only a few years later.

Notice the smile that is shared by these two figures, both created in the mid 6th century BCE. It is likely that Etruscan sculpture influenced the late archaic style as this same grin appears on most of the late archaic kouroi and pediment sculptures. Along with the smile, which seems to have been intended to make the subject look unperturbed by life, the later sculptures present more natural rendering of musculature. The change from the early Archaic to the late archaic sculptural style is depicted below.

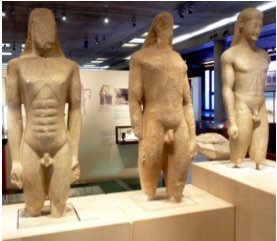

The three kouroi in this image are successively from later time periods going from left to right. The early kouros has incised lines and a pattern of ridges to indicate the torso muscles. The bottom of the ribcage is indicated by a sharp triangle. On the kouros at the far right the muscles of the arms as well as the torso muscles are more rounded and three-dimensional. The bottom of the ribcage is more naturally depicted and it is proportionally correct.

The Krosios Kouros was created late in the Archaic Period. It demonstrates nearly natural musculature, although it is highly idealized. His calf muscles are tight, showing that they are engaged. He still holds his hands in fists next to his thighs but the oblique muscles are no longer incised or raised ridges. They bulge in an idealistically powerful way, but are anatomically more natural than in earlier statues. The smile is present, although it is not as exaggerated as those from a few years earlier. This kouros still has a plaited hairdo and his eyes are still sitting on the surface of the face. Other details, however, are far more naturalistic. The navel is no longer a perfect circle and instead appears to be a naturally depicted belly button. Even his knees are tensed, indicating the growing interest in depicting accurate yet ideal anatomy. He is the 530 BCE. ideal man. Kouri like him are becoming more human in nearly every way.

DEVELOPMENT OF ARCHAIC TEMPLE SCULPTURE

The other place that sculpture of this period is seen is on the stone temples that had begun to be built for the first time since the Mycenaean culture had ruled centuries earlier. There were two areas of the Doric temple that were decorated with painted sculpture. The pediments were filled with visual representations of Greek Myths. Pediments are triangular areas under the gables of the temple roof and above the frieze. The other decorative spaces were the metopes. These are spaces created between the trigylphs which are decorative panels with three grooves or glyphs, which were also filled with mythic imagery. Like votive sculpture, the sculpture on Doric Temples became more naturalistic as time moved forward toward the Classical era.

On the Temple of Aphaia the pediments depict the battle scenes from the legendary war with Troy. Notice how the sculpture must be fit into a rather awkward space. As such, the most important figure stands in the center and the action seems about to begin around that figure. This temple is particularly helpful in viewing the progression of the naturalistic style of Archaic sculpture. Although the pediment sculpture is only a decade or two apart in origin, there is a marked difference in style from the East pediment to the West.

The west pediment was probably created when the temple was built, around 490 BCE. As such the figures are carved in the high archaic style. Once the Greeks almost miraculously defeated the Persians and their Greek allies a new attitude flowered. This is an attitude that had been building for some time in the Greek city-states. In 776 a cook won the Olympics. While one had to be a freeborn male citizen to compete, all competitors were treated equally. This may well have been the seed of the Humanism that comes into full flower following the defeat of the Persians in 479 BCE.

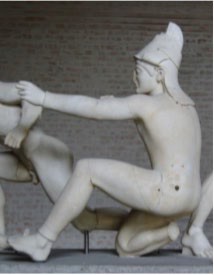

The figures on the west pediment are Archaic symbols and demonstrate everything that is expected of the style. They sport the Archaic grin, the stiff poses and the ideal but more symbolic than natural physicality associated with the growing Idealism and Rationalism of the mainland Greeks. The males are depicted nude, as they would be in an Olympic competition, a sign of pride in the well-developed physical specimen. They would not have fought nude in battle.

Notice that on the earlier pediment, Athena looks almost entirely Archaic in style. She sports the archaic grin and is in a stiff frontal position. This is perhaps the earliest figure that is almost in a contrapposto position in which the body parts are counter-positioned so that they are not in alignment with one another. Her left foot is turned slightly to the side. This does not, however, cause a twist in the rest of Athena’s body so it is not quite a contrapposto position. Like the kouros of the Archaic Period, this statue of Athena is primarily a symbol. In this case, she is a symbol of war. The smile seems to be an attempt to make her appear unconcerned with fear and death. Like other Archaic figures, she is beyond this reality. She holds a spear and the triangular shape of the statue brings the eye to the head, suggesting her association with reason. She is not only the goddess of war but also of wisdom, as she was born from the head of Zeus. Athena is not the only figure on this pediment that displays this Archaic styling. She, like the others demonstrates an early attempt at indicating potential movement in a sculptural subject. The turned foot like the forward foot of her predecessors, fails to convey a life-like stance.

Note that the archer in the image above also has the Archaic grin. His back leg displays attention to how the muscles work, although the bunching of the muscle is as symbolic as it is natural. The other leg seems impossibly positioned when one would expect the forward foot to be anchored. There are holes around the bottom of the hat, suggesting that some indication of hair was originally seen escaping the confines of the hat. Although the body is clothed, the muscles are revealed in such a way that the clothes cease to exist unless one is looking directly at the cuff of the leggings. Again, strength is being demonstrated and it is more important than any desire to create a natural position.

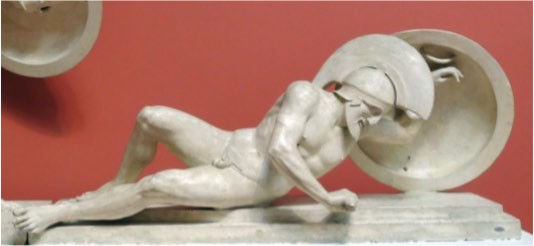

This dying warrior is perhaps the best sculpture to compare to the statues on the East pediment as it is clearly a different style than the dying warrior on the East Pediment, created only ten or twenty years after the West pediment sculptures were carved. The figure above is in an impossible position. It is a position that displays the strength of his legs, although it makes little sense to have the right leg over the left, except to show it off. The arm that the figure uses to pull what must be an arrow out of his torso is flexed and strong but is not natural. His right arm holds him in a reclining position that looks more relaxed than painful. The most alarming thing about trying to view this as anything but symbolic is that he sports a grin that is diametrically opposed to the image of a dying man pulling an arrow out of his body. The symbolism associated with the archaic style ceased to work once sculptures began to be presented in action.

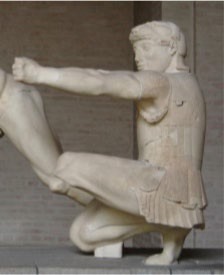

When viewing the archers side by side, it is easy to see that the later sculpture is more natural and less a symbol than the earlier one. The latter figure has a clear distinction between his clothing and his body. Rather than showing off his strength in a presentational way, it is displayed through his more carefully rendered musculature and his look of determination. Notice that although he still has a smile, it is not as broad and as such is less incongruent with the action of the image. His clothing seems to move a bit as he positions himself. The arm that holds the bow is flexed in a believable way. He is still ideal but he is also more natural in his depiction than his predecessor. Even his eyes look more natural as they are a bit recessed, rather than sitting on the surface of his face.

The difference between the pediment sculptures can be seen most clearly when comparing the two dying warriors. The more recent figure struggles to hold himself up as his weight seems to drag him down. His arm muscles are engaged and tensed. The right leg is no longer placed in front of the left. His body is no longer presenting strength in a frontal way. He is no longer merely a symbol of strength but is now an image of the bravery that it takes for a human to succeed in battle. He dies nobly and although there is still a trace of the archaic smile, he looks down and it can be read as a grimace. His body is still ideally proportioned but it is no longer what is on display. The trace of a smile still indicates a sense of not allowing circumstance to bring one down. Like other archaic statues, this one is not allowing himself to be affected by the horror that he is experiencing. This time, however, the figure seems to be more than a symbol, he is human.

The sculptures on the more recent east pediment of the Temple of Aphaia were carved about the same time as the Kritios Boy, which is considered the first fully classical sculpture. He is a kouros because although he shares the traits of the fallen warrior, unlike the warrior, the boy has no trace of a smile and so, he fulfills the expectations of the new classical style in every way.

References:

1. Metropolitan Museum of Art [CC0] https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/a/a8/Marble_statue_of_a_kouros_%28youth%29_MET_DT263.jp g

2. Metropolitan Museum of Art, CC0, Public Domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hatshepsut_in_a_Devotional_Attitude_MET_21V_CAT094R4.jpg

3. Metropolitan Museum of Art [CC0] https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/1/19/Marble_statue_of_a_kouros_%28youth%29_MET_gr32.1 1.1.AV2.jpg

4. Metropolitan Museum of Art [CC0] https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/1/13/Marble_statue_of_a_kouros_%28youth%29_MET_gr32.11.1 .AV1.jpg

5. CC BY-SA 3.0 https://www.flickr.com/photos/profzucker/14976901108

6. Greek, Attic; Head of a kouros (youth); Stone Sculpture. CC0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Marble_head_of_a_kouros_(youth)_MET_DP282090.jpg#/media/File:Marb le_head_of_a_kouros_(youth)_MET_DP282090.jpg

7. Terracotta antefix (roof tile) Metropolitan Museum of Art [CC0] https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/f/f3/Terracotta_antefix_%28roof_tile%29_MET_DP207966.jpg

8. Photo by O. Mustafin, CC0, Collection of Archaeological Museum of Thebes.

9. Photo by National Archaeological Museum, CC BY-SA 3.0 , https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/0/04/0006MAN-Kouros2.jpg

10. Photo by Giebelfiguren vom Aphaia Tempel Glyptothek, CC BY-SA 3.0 https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/9/97/Giebelfiguren_vom_Aphaia_Tempel.JPG

11. Photo by W-I Glyptothek Munich Glyptothek, Public domain, https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/e/ea/Aphaia_pediment_Athena_W-I_Glyptothek_Munich_74.jpg

12. Photo by Bibi Saint-Pol, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Aphaia_pediment_Paris_W-XI_Glyptothek_Munich_81.jpg

13. W-VII Glyptothek [Public domain] https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/7/74/Aphaia_pediment_warrior_W-VII.jpg

14. Photo by Bibi Saint-Pol, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Aphaia_pediment_Paris_W-XI_Glyptothek_Munich_81.jpg

15. Glyptothek [Public domain] https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/9/94/Aphaia_pediment_Herakles_E-V_Glyptothek_Munich_84.jpg https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:East_pediment_- _Temple_of_Aphaia_in_Egina_-_Glyptothek_-_Munich_-_Germany_2017_(2).jpg

16. W-VII Glyptothek [Public domain] https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/7/74/Aphaia_pediment_warrior_W-VII.jpg

17. Photo by shako, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/b/b4/Warriors_from_East_pediment_of_the_temple_of_Aphaia_%28casting_in_Pushkin _museum_after_Munich_original%29_by_shakko_04.jpg