8.6 The Junction of East and West: Hagia Sophia

Rome fell several times—to the Visigoths (in 410), the Vandals (in 455) and the Heruli (in 476)—but Ravenna went from strength to strength, first under the Ostrogoths and then under the Byzantines. Great churches were built and beautiful mosaics were made to decorate them. From 540-751 Ravenna remained the administrative center for “Roman” Italy, which meant in effect that it was a Byzantine outpost in the West. But the Byzantine dream of reuniting East and West into a single empire was destined to fail, and slowly Ravenna as well as the port of Classe gradually silted up and lost their status.

Constantinople had its challenges, as well. Constantine’s vision that the new capital would be free from scenes of plot and counterplot, treason and conspiracy, was just that—an illusion.2 We resume the story of Constantinople in 527. The new Byzantine emperor (and thus Roman emperor), Justinian I, regarded his rule as universal, so he sought to re-establish the authority of the Empire in Western Europe. He had other reasons as well for seeking to re-establish imperial power in the West. Both Vandal Carthage and Ostrogoth Italy were ruled by peoples who were Arians, regarded as heretics by a Catholic emperor like Justinian.

Among other qualities, Justinian is remembered for being both an incredibly fervent Christian and a major military leader. One aspect of Justinian’s focus on Christian purification was to complete the work initiated by his Christian predecessors: the destruction of the ancient traditions of paganism in Greece and the surrounding areas. The Olympics had already been shut down by the emperor Theodosius I in 393 CE (he objected to the pagan religious festival, not to the athletic competition). Justinian intensified the push by insisting that all teachers and tutors convert to Christianity and renounce their teaching of the Greek classics; when they refused in 529, he shut down Plato’s Academy which had been functioning for almost 1,000 years.

With the intent of emphasizing his own greatness as well as that of his empire, Justinian undertook many art and architecture projects. Much of Constantinople had burned down early in Justinian’s reign in 532 after a series of revolts called the Nika riots. As the “last straw” in a confrontation over rising taxes, angry racing fans had became enraged at Justinian over the arrest of two popular charioteers. Included in the destruction by the “chariot hooligans” was the Church of the Holy Apostles which had originally been built by Emperor Constantine I in 325 over the foundations of a pagan temple. Once the tumult was under control, Justinian set about rebuilding the city on a grander scale. His greatest accomplishment was the total reconstruction of Constantine’s church [image 8.120]. The architects, Anthemius of Tralles and Isidorus of Miletus, were most likely influenced by the mathematical theories of Archimedes (c. 287-212 BCE). Justinian’s new church, constructed adjacent to the imperial palace between 532 and 537, was a staggering work intended to awe all who set foot in the structure. It was not only the most enduring piece of Byzantine architecture; it was the largest church in the world for nearly a thousand years.

Like Rome, Constantinople had been built on seven hills. Hagia Sophia is located on the highest of these, upon which the ancient city of Byzantium had been founded. The church reflects the blending of two continents (Europe and Asia), two seas (the Black Sea and the Mediterranean), two languages (Greek and Latin), and two plans (basilica and central). The church represents the junction of East and West.

The church was built in the remarkably short period of five years and ten months. To speed the process along Justinian divided the workers into two groups with bonuses offered to the faster team. (Microsoft would apply a similar incentive 1500 years later to research and development teams!) The story is told that at the dedication on Christmas Day, 537, Justinian charged his chariot into the church proclaiming, “Glory to God, who has judged me worthy of accomplishing such a work as this! O Solomon, I have outdone you!”

This diptych at the Louvre is thought to represent an emperor [image 8.121]. It could be Anastasius (r. 491-518) but Louvre curators state the style is more likely that of Justinian (r. 527-565). When this author visualizes Justinian boisterously galloping into the church she can’t help but connect this diptych to his boastful declaration.

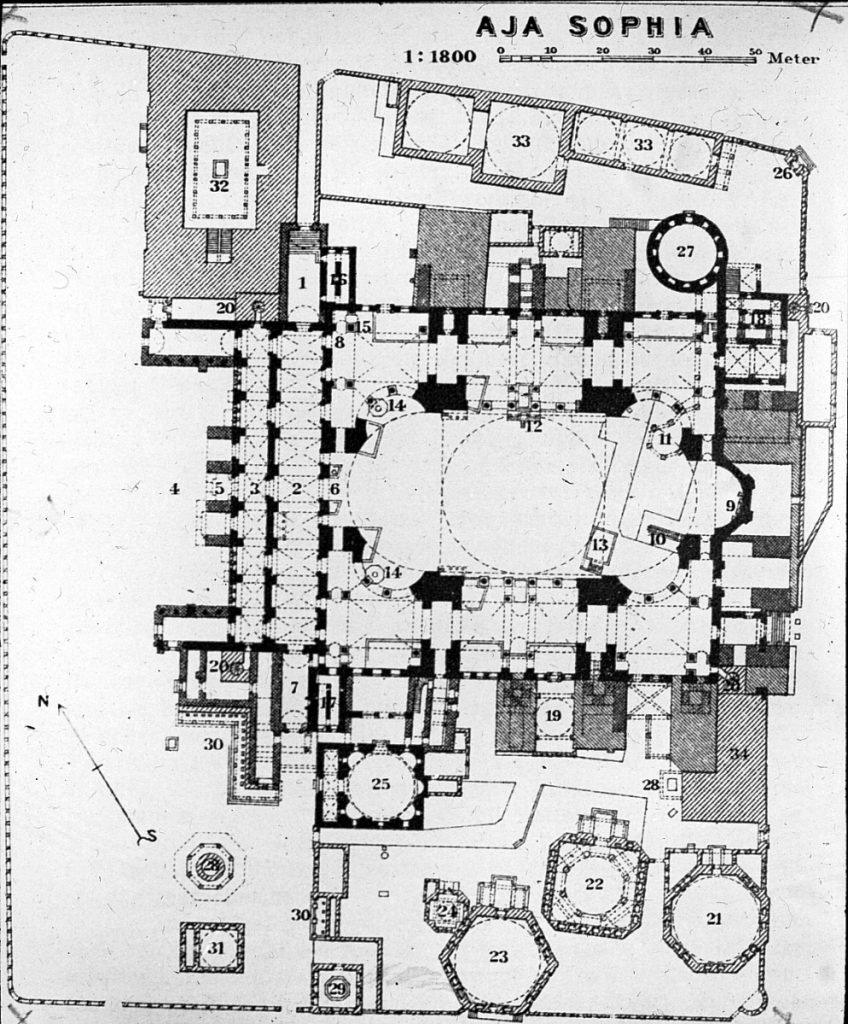

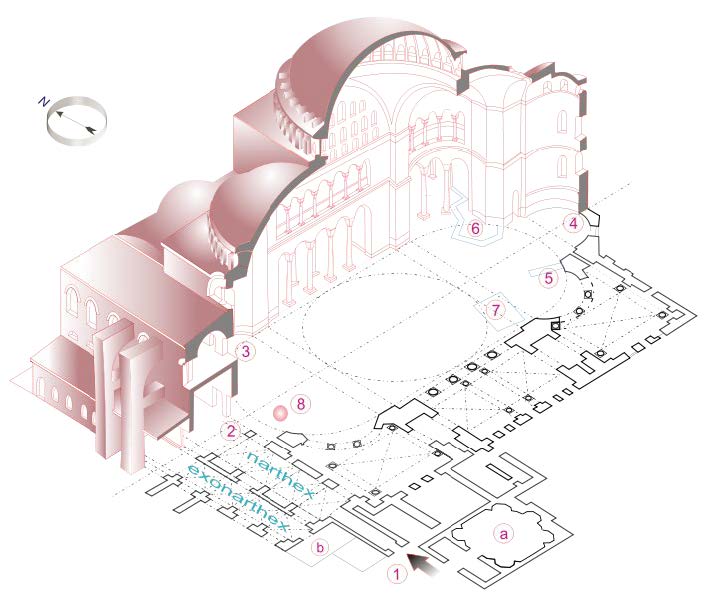

Look around the exterior of the structure as well as at the plans [images 8.122 and 8.123]. The axis is horizontal as well as soaringly vertical, while the orientation is towards the east. Remembering that circles suggest continuity and infinity, where do you see circles? Recalling that squares imply the active life and humankind’s physical aspirations, where do you see squares or rectangles? Where do you observe the intentional use of the mystical numbers 3 and 4? Here, the mysticism of the east is united with Roman authoritarian architecture.

The height of the dome is 184’ and its diameter is 107’. The interior measures 220’ by 250’ which is the size of three modern football fields. This will be the largest enclosed space in the world for over 1000 years.

The viewer’s gaze sweeps around the space, drawing one’s eyes up and forward, not stopping to focus on any one section or image [image 8.124]. What makes Hagia Sophia so mystical?

Hagia Sophia is a supreme example of the creation of a spacious and light-filled interior. Since the installation of clerestory windows into basilica churches in the fourth century, light had been a principal requirement of church architecture. Light represents wisdom (Sophia!), the word of God, the light of the world, and is symbolic of the Resurrection. Light denotes the presence of God and leads the believer to progress anagogically7 from this material world to the immaterial world. Justinian’s historian, Procopius, related the psychological and religious effect of mystical light and the graceful interior: “The worshippers mind rises sublime to commune with God, feeling He cannot be far off, but must especially love to swell in the place which He has chosen; and this takes place not only when a man sees it for the first time, but it always makes the same impression upon him, as though he had never beheld it before.”8

Around the corona of the dome an arcade of 40 arched windows illuminate the colorful interior. Additionally, this ring lightens the weight of the dome and allows some movement during severe earthquakes, preventing meridional cracking.9

Within the church the light reigns free. Thousands of lamps glitter on the mosaics. The dome alone is covered with 30 million cut glass tesserae infused with gold leaf. Interior light reflects off cornices, doors and doorframes. The sanctuary barriers are of polished bronze and 40,000 pounds of silver and light shines forth from polished green, white and purple marble. Additionally, the dignitaries are wearing rich, light-reflective, textiles.

Procopius, again writing in De Aedificiis, compares the suspension of the dome to the Greek poet Homer’s vision of Zeus suspending the whole world from Mount Olympus, as recounted in The Iliad. “The dome is so light that it does not appear to rest upon a solid foundation, but to cover the place beneath as though it were suspended from heaven by the fabled golden chain.” This crown in image 8.126, which is similar to Justinian’s, may look familiar to you!11

The windows at the bottom of the dome [image 8.127] are closely spaced, visually asserting that the base of the dome is insubstantial and hardly touches the building itself. The building planners did more than squeeze the windows together; they also lined the jambs or sides of the windows with gold mosaic. As light hits the gold it bounces around the openings and eats away at the structure, making room for the imagination to see a floating dome.

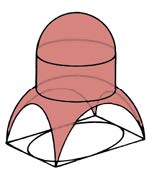

The growing importance of relics stimulated churches to be built in the Central plan. At Hagia Sophia the dome sits over the central bay. Concave triangular pendentive arches, each springing from a single pier, carry the circle of the dome [image 8.128]. Despite the enormous forces created by domes and the exceptional technical problems of their construction, the domes enabled a far wider and more open basilica layout than would have been possible had even the longest roof timbers been employed. As if to demonstrate their muscular strength, each of the pendentives around the corona hosts a depiction of an angel.15

Around the dome, exedrae (recessed semidomes) on either side of the dome were both useful and served to buttress the dome. These, in turn, were supported by their own smaller semidomes.

Simultaneously, the time-honored basilica plan was still utilized. Hagia Sophia clearly has a narthex, nave, aisles, a crossing (under the dome), and an apse. Processions and prostration, in honor of the emperor, were expected.

Constantine’s fascination with relics20 was not forgotten here, with mementos chosen to meet every theological persuasion. From Jewish tradition, the faithful could see the adz with which Noah’s ark had been build, the olive branch carried by the dove to signal that the flooding waters had receded, the rock in the desert which Moses struck to bring forth water and the ram’s horns which Joshua blew to bring down the walls of Jericho. Christians could view a casket containing crumbs leftover from the feeding of the 5000, an alabaster box containing ointment with which Mary Magdalene anointed Jesus, the lance that pierced Christ’s side, Christ’s tunic, the Crown of Thorns, a vial of Christ’s own blood, fragments from the True Cross and the crosses of the two thieves with whom he had been executed. For citizens who honored both Jewish and Christian traditions, Hagia Sophia had the arm and head of John the Baptist21 and the well-head from where Christ had met the Samaritan woman. For good Roman citizens, the basilica held the standard carried to Rome by the mystical founder, Trojan prince Aeneas. The relics and the church were consecrated with a grand banquet at which 6000 sheep, 1000 oxen, 1000 pigs, 1000 poultry and 500 deer were served.

At the top of the south wall a 10th century construction worker doing repair work left his prayer, “Lord, help your servant…” We can imagine a grunt laborer, without benefit of safety-net or OSHA regulations, looking down 184 feet and hoping his prayer will be heard.

Most of the original mosaics were not figurative images. Geometric and floral patterns were on the ceiling and upper walls. The mosaic shown in image 8.133 was uncovered after the 1934 restoration of the facility.

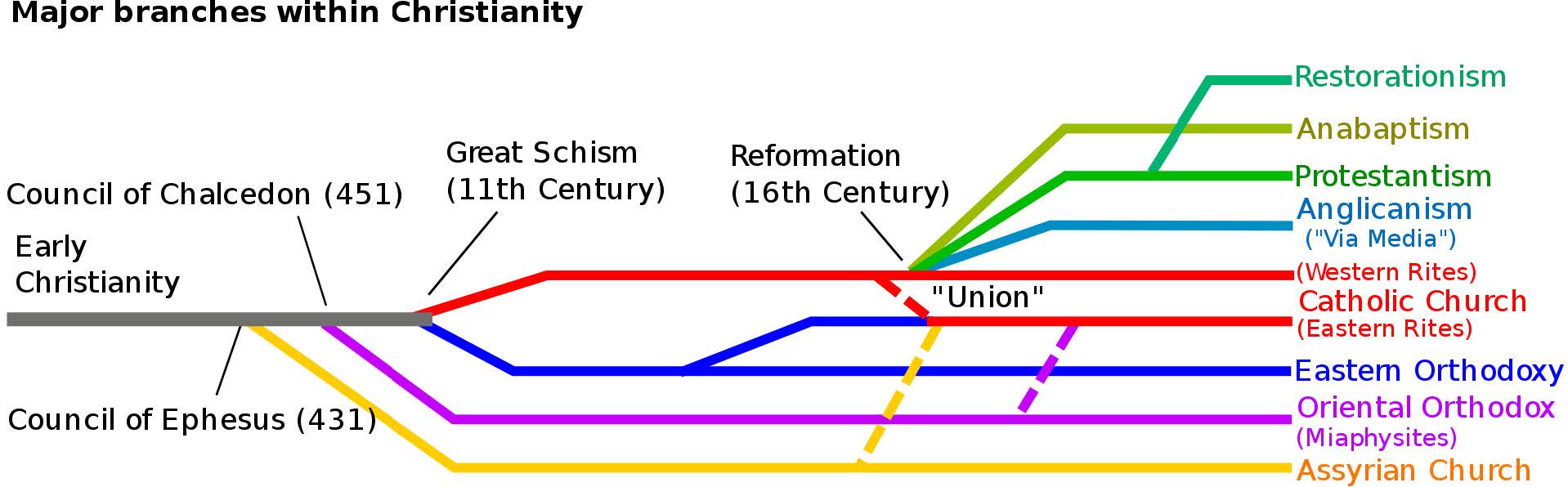

One of the crises faced by the Byzantine court is known as the Iconoclast Controversy. The word icon refers to many different things today. For example, we use this word to refer to the small graphic symbols in our software as well as to powerful cultural figures. The changed meaning of “icon” derives from the word’s original meaning which was from the Greek word for “image” or “painting.” During the medieval era, this meant a religious image on a wooden panel to be used for prayer and devotion. Christians living in the eastern Mediterranean used icons (paintings of Christ, the Virgin Mary or the saints) as worship aids. Other Christians, citing the Ten Commandments’ prohibition on “graven images” opposed the images as “idols.”

Pope Leo III (r. 717-747) was right at the heart of the controversy. It was widely held that Muslims were Christian heretics, worshipping the same God but in an incorrect way. Since Muslims had chosen to eschew images in their mosques, and they were extraordinarily successful in battle, the pope and his advisors reasoned that God might be punishing the Byzantines for misusing religious images and for falling into idolatry. The solution appeared simple: ban the use of religious images and hope for divine approval, which would become apparent through political and military success. So, in 726 he banned all icons. As they say, the proof is in the results: Pope Leo III reigned 25 years, longer than his five predecessors combined. The conclusion: God must have liked Leo and his stand on iconoclasm!

The period from 717-867 became known as the Period of Iconoclasm. Early Christian art was not the only thing destroyed; it has been estimated that 50,000 monks, with their “modern” interpretation of the significance of the Virgin, were exiled to Italy during this time.

In 843 a new pope, Pope Gregory IV, repealed the ban and iconophiles (aka iconodules) resumed their activities. From this date forward Greek-speaking churches would support the use of icons. These will be the followers of the Eastern Orthodox tradition. In 867 the pope’s action was supported by the Emperor Basil I

The Theotokos (“God-bearer”) in the conch of the apse is one of those images installed after the Iconoclast Controversy [images 8.134-136]. It is similar to the stylistic elements of early Christian art and was probably approved by the Emperor Basil II (r. 986-994). The enormous size of Hagia Sophia makes the Theotokos look remote and removed from humankind but she is actually 16’ 4” high, which is three-times life size!

Placed against a golden background, gold tesserae isolate the figure and eliminate every indication of time and place. In mosaics and painting this golden background was properly termed “gold ground.” The reflecting light surrounding the icon shines back to the beholder, projecting the figure forward into the space between the observer and the image. This was especially true when candles were set before the icon.

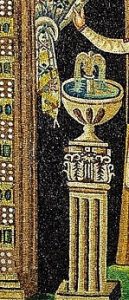

In Byzantine art the projection of the heavenly figure into the earthly realm was also accomplished mathematically. In the geometric technique of Byzantine perspective, lines converged forward to enhance the viewer’s sensation of being included in the composition. The practice is also referred to as reverse perspective or inverted illusionism.xxvii Figures were elongated and objects appeared to be heightened and tip upward. The foreshortened view does not distort the image when seen from below and at a distance. Examples of Byzantine perspective are to be seen at the top of the fountain beside the Empress Theodora [image 8.137] and the bema (raised platform) upon which the Theotokos sits [repeated image 8.138].

Byzantine perspective was an additional response to the Platonic influence on Byzantine art. The argument given in the Timaeus was that human eyesight is imperfect and untrustworthy. Objects don’t really decrease in size as they recede in the distance. As Plato advised, earthly illusions are not to be trusted!

Byzantine, Romanesque and Gothic artists continued to extend space forward, bringing the icon to the viewer. Byzantine perspective, with the introduction of the divine into our world, was further mastered by the stained glass artists of the Gothic cathedral. Using the mystery of light, the saints bridged the divide between the heavenly world and this terrestrial plane. The convention of Byzantine Perspective is still to be seen in the painted and gilded panel known as the Kahn Madonna [image 8.139]. The artist, possibly from Constantinople, may have brought the traditional Byzantine perspective with him when he immigrated to Italy. It will be the privilege of later Proto-Renaissance artists, such as Cimabue (c.1280+), to introduce the angle of “linear perspective” with which we are familiar.

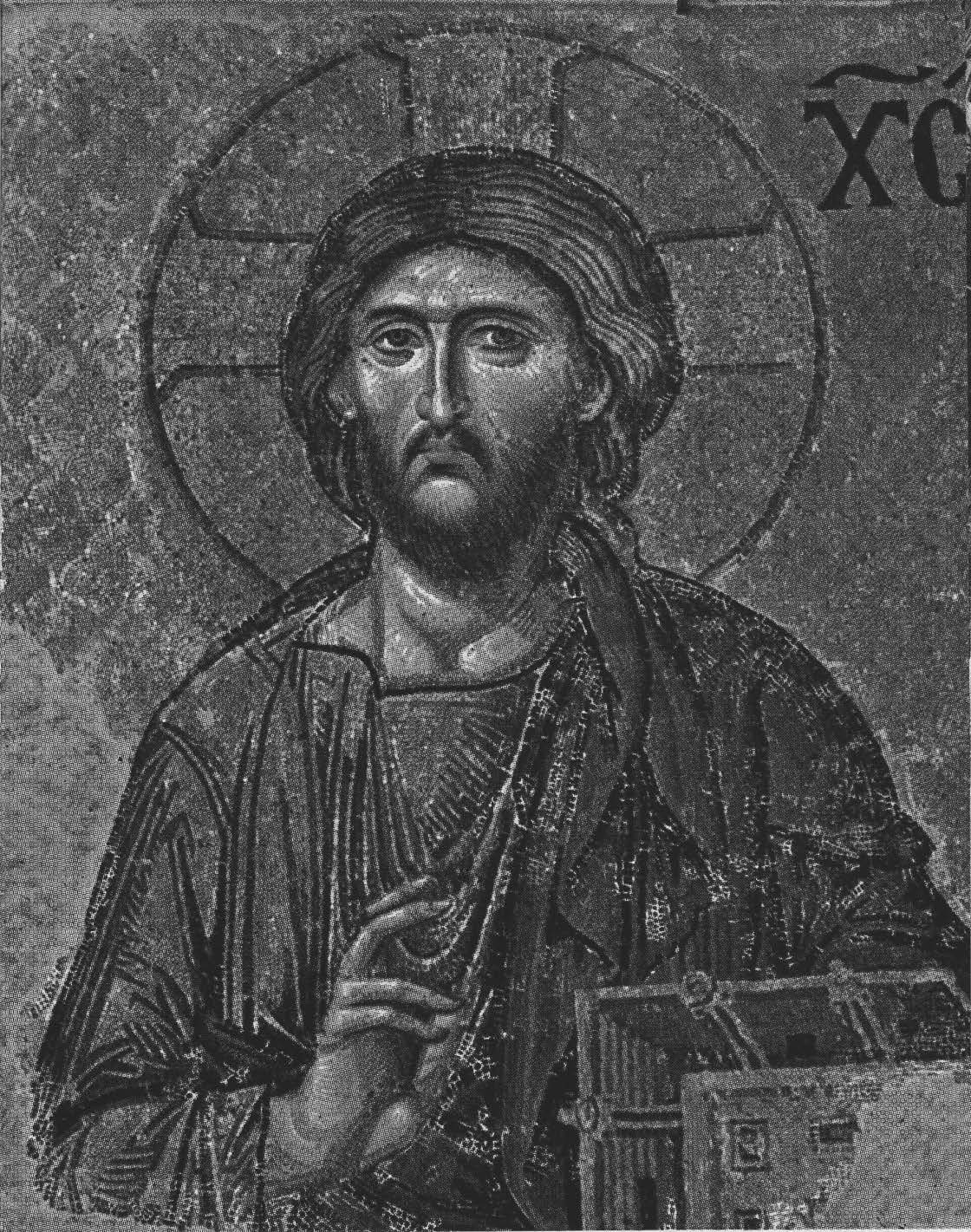

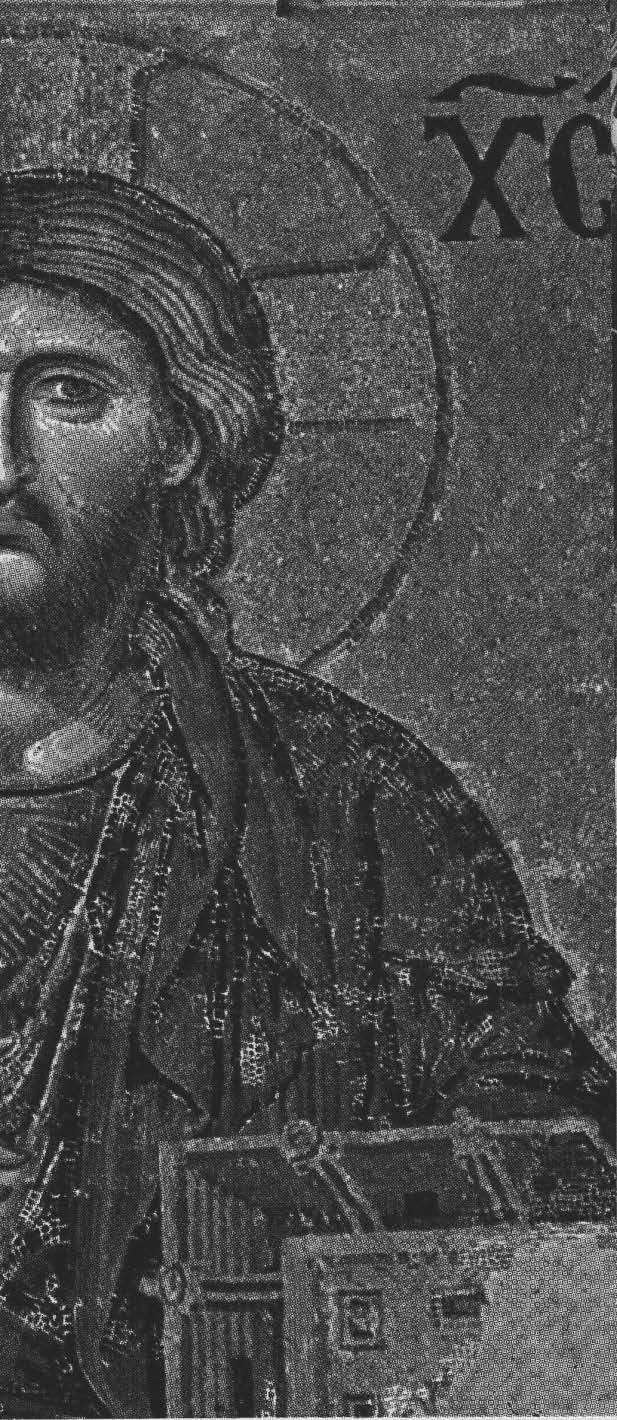

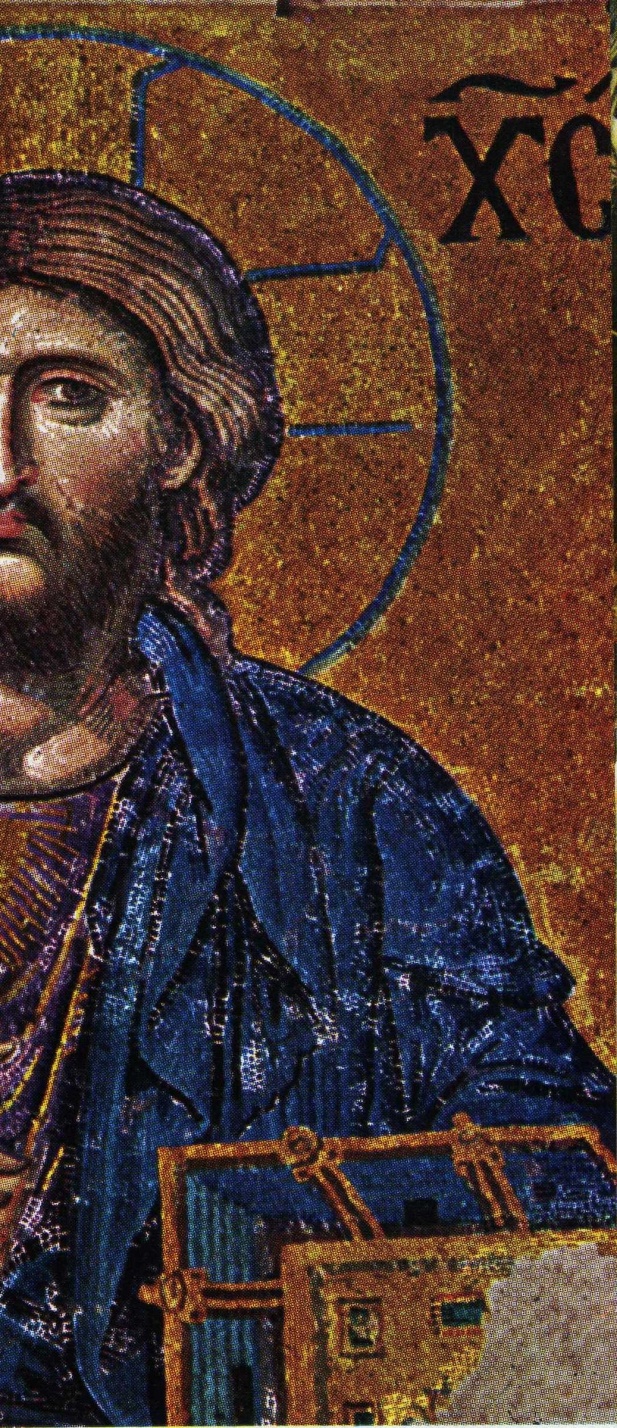

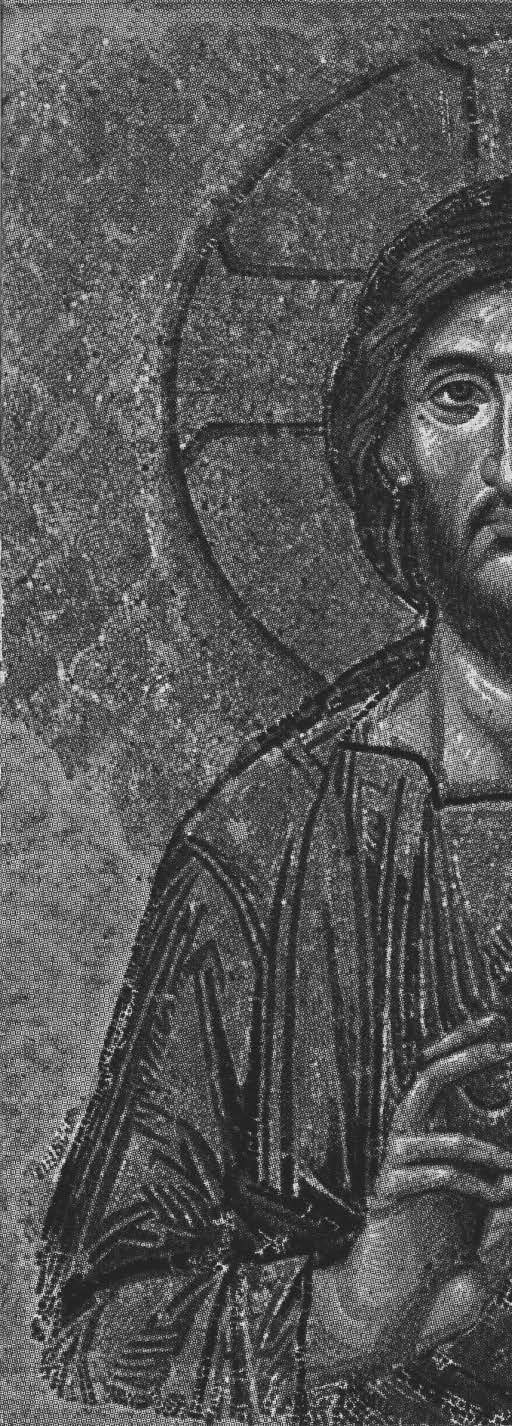

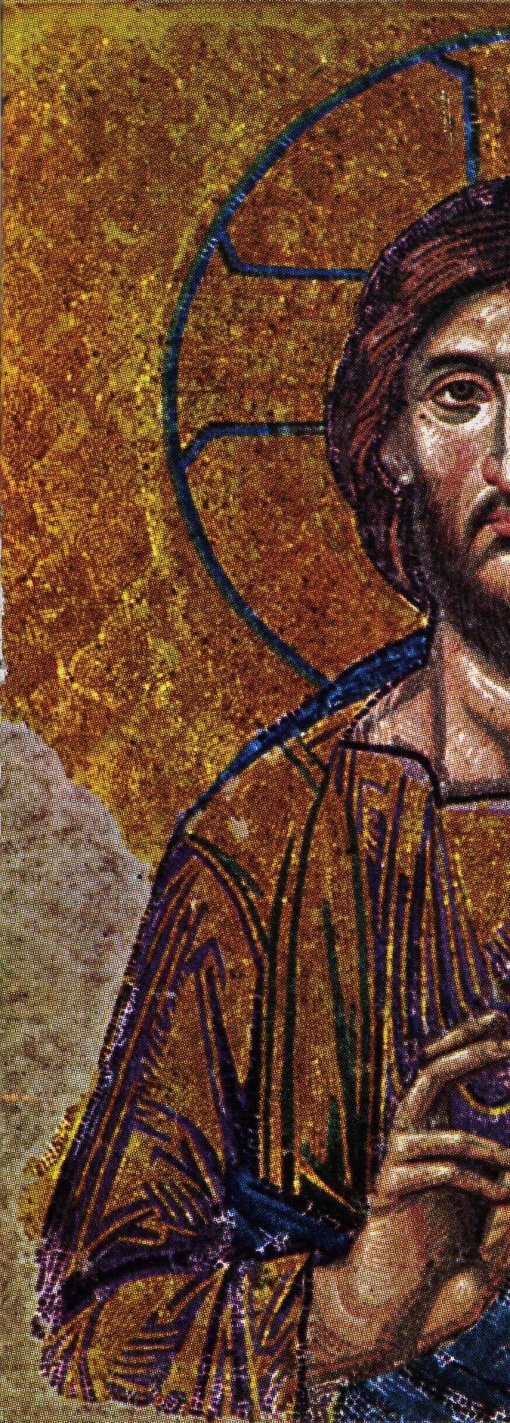

The panel in the south gallery known as the Deësis is a bit smaller, with the figures at two-and-one-half times life size [images 8.140-147]. This image of the Virgin, Christ in Majesty and John the Baptist is thought to have been installed in 1261 after the Crusaders had been expelled from the city. The gold ground upon which the figures are mounted presents them as eternal: they are always present to receive prayers and supplications. This mosaic was much more accessible to those converting the church to a mosque in 1254. It was easily covered with layers of whitewash, not because the Muslims don’t recognize Christ as at least a prophet but because of the prohibition of figural imagery, especially within a religious space. It was uncovered in 1934 when the mosque was converted into a museum.

Certainly we are caught by the riveting stares of these figures. The eyes of the Virgin, Christ and John the Baptist remind us of the Faiyum portraits.33 Clearly their eyes are intended to be windows to their souls. The skill of the unknown artist is amazing. Notice how the light source, raking across from our left, is matched by the shading of the faces. Gold tesserae of the cross within Christ’s halo is laid with swirling patterns and set at 30o to the vertical, thus ensuring they will catch the light in a different way.

The Latin letters IC symbolize “Jesus Christ.”35 The position of his fingers reinforce this abbreviation. The Greek XC stands for “Christ.” ΜΡ is Byzantine for “Mother of the King” or “Theotokos.”

Reducing the image to a value contrast of black and white encourages us to look at the icon in a new way. Do you find the image to be open, receptive and welcoming or harsh and judgmental?

Most students find this icon to be unkind, confrontational and critical of humankind. But the Byzantine churchman Nicholas Masarities, writing in about the year 1200, declared, “His eyes are joyful and welcoming to those who are not reproached by their conscience…But to those who are condemned by their own judgment, they are wrathful and hostile.” How did the very skilled artist accomplish both attitudes in one work?

Our eyes are drawn to the dark side, to Christ’s left side (our right). “Left” (as in the French gauche) is considered the awkward, sinister or unkind side of a person. He clutches a book which is illustrated in Byzantine perspective. This is the Book of Life in which are written the names of those who are saved (according to Philippians 4:3). How do the elements of art emphasize the judgmental left side?

• Lines: his eyebrow is more arched. His mouth is drawn into a sneer. The implied presentation is downward.

• Light and shadow: his cheekbone is accentuated with shadow. The colors of blues and blacks are also heavier and darker.

His right side brings the relief we need! His fingers spell out the Latin letters I and C (i.e. JC for Jesus Christ) which are also printed over his head. Or, the two raised fingers could represent his two natures of divine and human. On this side the dominant “kinder” element is color. There is more gold (representing heaven, light, eternity, brightness and hope!). The blue is brighter, representing the sky, divine truth and steadfast faith.

This is not an idol; it’s an icon. Because of the devotional attitude attached to the image, the icon becomes a window or a door through which the worshipper gazes into heaven and gains access to the holiness of the saints. Naturalism and true to life details have no place here. The intent is to portray the mystical, the divine aspect of the dual nature of Christ who was understood to be both God and man. In the same way that the Eucharist (Holy Communion) embodies Christ’s flesh and blood, an icon embodies the presence of the holy figure.

Icons demand concentration upon that which is essential about the holy person. For inspired reverence and meditation, the viewer is called upon to focus on the sanctity or worthiness of the holy figure instead of our customary focus on this mundane world of extraneous human qualities, body mass and human emotion. Not everybody gets it! A symbol is a real thing, invested with unreality.

At Hagia Sophia the church, itself, was an icon. It was not just brick and mortar. It was believed to be heaven’s door to earth. As a symbol of God’s universe the church was a vehicle of communication between God and man. Hagia Sophia was never copied but it did set a standard of architectural excellence which influenced ecclesiastical architecture throughout the Balkans and the Near East and in due course into areas that had never been Romanized such as the Christian principalities of Russia.

You might appreciate this video about the Deësis at Hagia Sophia (5:08):

If you have difficulty viewing the video above, use this link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2JxIjfqKTLs.

References:

1. Map uploaded from Wikimedia Commons by brewminate.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/ByzantineEmpire04.gif

2. See Hartman, Kathleen J. “Chapter 7, Constantine’s Great Decisions.” Humanities: New Meaning from the Ancient World. Colorado Springs, CO: Pikes Peak Community College, 2020. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

3. Public domain at https://pxhere.com/en/photo/1075731

4. Photo by the author, Kathleen J. Hartman, 2014. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

5. Public domain at upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/3/38/S03_06_01_003_image_1753.jpg

6. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hagia_Sophia_Segment.svg

7. French Abbot Suger gave a superb definition of “anagogical” in his writings about the first Gothic cathedral of St. Denis in Paris, 1149. “Thus when—out of my delight in the beauty of the house of God—the loveliness of the many-colored gems has called me away from external cares, and worthy meditation has induced me to reflect, transferring that which is material to that which is immaterial, on the diversity of the sacred virtues: then it seems to me that I see myself dwelling, as it were, in some strange region of the universe which neither exists entirely in the slime of the earth nor entirely in the purity of Heaven; and that, by the grace of God, I can be transported from this inferior to that higher world in an anagogical manner” (De Administratione, XXXIII).

8. Procopius, De Aedificiis.

9. Related video Engineering Secrets of Hagia Sophia, August, 1999 on https://vimeo.com/12478063

10. Copied from Wikimedia Commons by brewminate.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Berger04.jpg

11. See Hartman, Kathleen J. “Chapter 8, Justinian, Master of Three Powers: San Vitale.” Humanities: New Meaning from the Ancient World. Colorado Springs, CO: Pikes Peak Community College, 2020. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

12. Public domain at upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/f/f2/Corona_de_%2829049230050%29.jpg

13. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Istanbul_036_(6498284165).jpg

14. Public domain at human.libretexts.org/Courses/Achieving_the_ Dream/Book%3A_ Art_History_I/ 2%3A_ Byzantine_ Art/12.5%3A_Hagia_Sophia

15. The root of our word “angel” is “evangelos,” not “angle!”

16. Public domain at human.libretexts.org/Courses/Achieving_the_Dream/ Book%3A_Art_History_I /12%3A_ Byzantine_ Art/12.5%3A_Hagia_Sophia

17. Public domain at Team, Hagia S. R. “The Seraphim Mosaic.” Ancient History Encyclopedia. Ancient History Encyclopedia, 22 Jan 2018. Web. 05 Nov 2019.

18. Public domain at upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/6/63/Penditifkuppel-mit-Tambour.png

19. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Istanbul_036_(6498284165).jpg

20. See Hartman, Kathleen J. “Chapter 7, Relics of Faith.” Humanities: New Meaning from the Ancient World. Colorado Springs, CO: Pikes Peak Community College, 2020. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

21. John the Baptist’s head is also claimed to be at San Jean of Angely in southwestern France. His other head?

22. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category: Interior_of_Hagia_Sophia#/media/ File:20131203_ Istanbul_022.j

23. Public domain at hagiasophiaturkey.com/mosaics-hagia-sophia/

24. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Istanbul_036_(6498284165).jpg

25. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Virgin_and_Child_Mosaic_in_the_apse_of_Hagia_Sophia.jpg

26. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Virgin_and_Child_Mosaic_in_the_apse_of_Hagia_Sophia.jpg

27. This author prefers the term Byzantine perspective. “Reverse perspective” has a negative, judgmental ring to it, as though the artist hasn’t studied his math or is being contrary and doing things “perversely” just to be a heretic. “Inverted illusionism” is another term that is sometimes used, but to this author this term is just too verbose.

28. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Virgin_and_Child_Mosaic_in_the_apse_of_Hagia_Sophia.jpg

29. Cropped from mosaic of Theodora and Her Retinue at San Vitale. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki /File:Mosaic_of_Theodora_-_Basilica_San_Vitale_(Ravenna,_Italy).jpg

30. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Italo-Byzantinischer_Maler_des_13._Jahrhunderts_001.jpg

31. Public domain at www.flickr.com/photos/profzucker/14068355978/in/photostream/lightbox

32. Public domain at https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hagia_Sophia_Interior_(2099879592).jpg

33. See Hartman, Kathleen J. “Chapter 7, Anticipating Byzantine Culture.” Humanities: New Meaning from the Ancient World. Colorado Springs, CO: Pikes Peak Community College, 2020. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

34. Public domain at www.khanacademy.org/humanities/ap-art-history/early-europe-and-colonial-americas/medieval-europe-islamic-world/v/deesis-mosaic

35. There is no J in Latin. You will see this substitution of I for J in the four letters which are posted as a placard on Jesus’ crucifixion cross: INRI, meaning “Jesus of Nazareth King of the Jews.”

36. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hagia_Sophia_Deesis_mosaic_(2).JPG

37. Public domain at pxhere.com/en/photos?q=hagia+sophia+pantocrator

38. Ibid (reproduced in black and white).

39. Ibid.

40. Ibid.

41. Public domain at en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Non-Chalcedonian_Christianity#/media/File:Christianity_major_branches.svg