4.4 The Mycenaean Culture

On mainland Greece and in the Peloponnesus two Mycenaean Kings ruled in a manner that would influence Spartan rule in the same area hundreds of years later. Ruling together, the legendary kings made war on Troy, across the Aegean Sea in what would become Persia, and became the subjects in the ancient Greek tale of the fall of Troy called The Iliad.

Go to the site: Smarthistory.org click on “Ancient Mediterranean” then on “Ancient Aegean” then, “Mycenaean” and “Mask of Agamemnon.” Watch the four-minute video for a great overview of the Mycenaean’s place in the ancient world.

Mask of Agamemnon Video (3:52)

If you cannot view the video above, use this link: https://smarthistory.org/mask-of-agamemnon/

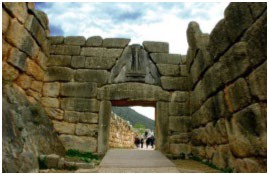

The Lion’s Gate makes it clear that this civilization was sophisticated and stratified. A visitor to Mycenae passed through this imposing gate on their way into the citadel. Lions are traditionally a symbol of kingship and the fact that there are two lions above the gate is likely a reflection of the double-king system that seems to have been practiced at some time by Mycenaean royalty and later by the Spartans.

There is an image found at Mycenae that suggests that there was once a goddess above the column that stands between the lions. Notice in the Minoan image to the left that displays such a goddess who is flanked by lions that look a good deal like those in the Mycenaean image.

4.29 Artreus’ Tholos Tomb Interior.6

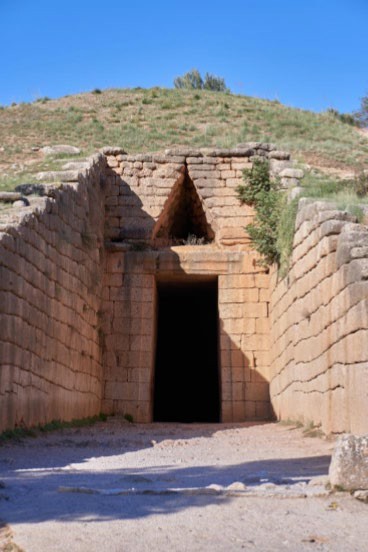

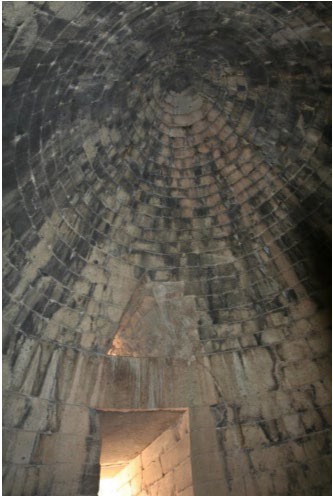

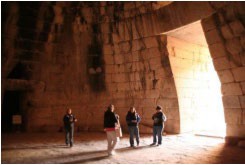

Tombs from the Mycenaean period (1900- 1100 BCE.) were called Tholos or beehive tombs. Note the entrance to this royal tomb. The Treasury of Atreus, also called The Tomb of Agamemnon, is the largest of the nine tholos discovered at Mycenae. One of the most impressive aspects of these tombs is the construction of the ceilings. The beehive shape of the interior is called a corbel vault. By moving each succeeding layer of stone slightly inward a pointed dome is formed. This corbelling technique can also be seen on the entrance and on the Lion’s Gate.

As is clear in these pictures the tomb’s size is impressive. According to Encyclopedia Britannica, “The diameter of the tomb is almost 50 feet (15 meters); its height is slightly less. The enormous monolithic lintel of the doorway weighs 120 tons and is 29.5 feet (9 meters) long, 16.5 feet (5 meters) deep, and 3 feet (0.9 meter) high. It is surmounted by a relieving triangle decorated with relief plaques.7

Gold and other riches were buried inside the tombs. This explains why this building is often referred to as Atreus’ treasury. Among the riches was the most famous artifact, known as, the mask of Agamemnon. The mask is actually about 400 years older than the time of Agamemnon, a legendary king who fought in the Trojan War. However, it is clear that Homer was not exaggerating when he described Mycenae as rich in gold. As was seen in the reclaimed architecture, there is some evidence that the mask depicted below may have been modified by the addition of a rather modern looking mustache.8

MYCENAEAN POTTERY

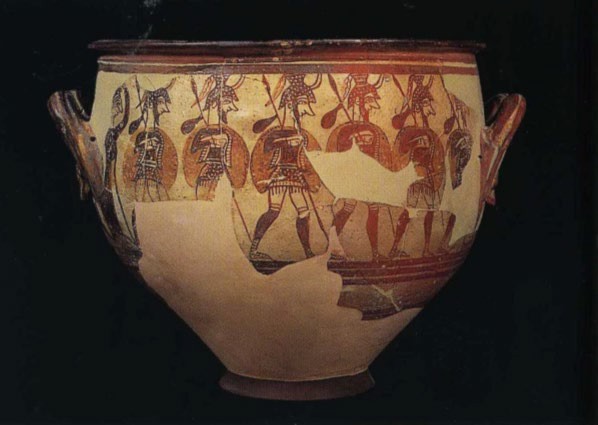

The Mycenaean civilization flourished in the late Bronze Age from the 15th to the 13th century BCE, and their artists continued the traditions passed on to them by Minoan Crete. Pottery, frescoes, and gold work skillfully depicted scenes from nature, religion, hunting, and war. Developing new forms and styles, Mycenaean art proved to be more ambitious in scale and range of materials than Cretan art and, with its progression towards more and more abstract imagery, it influenced later Greek art, particularly in the Geometric and Archaic periods.

This pottery provides valuable insights into the accuracy of Homer’s description of Trojan warriors and weaponry, if indeed there was a Homer. It is clear that whoever wrote down the story of the Iliad described weapons and other items used in war as he knew them in his own time, rather than as they were during the Bronze Age.

Early wheel-made Mycenaean pottery (1550-1450 BCE) from mainland Greece has been described as ‘provincial Cretan’ which does convey the fact that although shapes and decorative styles were of Cretan origin, the final decoration was not quite as finely executed as in Minoan centers such as Knossos and Phaistos. However, despite this difference in quality, it is likely that Cretan potters did actually relocate to the mainland. In terms of raw material though, Mycenaean pottery is in fact often superior in quality to Minoan as the majority was made from old Yellow Minyan Clay and fired at higher temperatures than on Crete. The designs themselves were painted using a red to black, lustrous, iron-based clay slip (or ‘paint’) which had a tendency to become mottled depending on the firing process.

THE EVOLUTION OF DESIGN

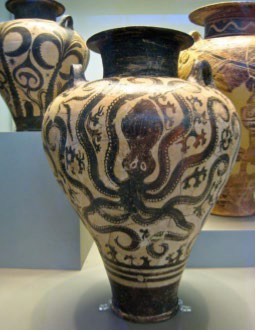

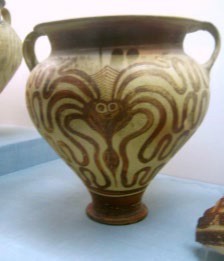

Over time, Mycenaean pottery decoration continued to become more and more abstract to the point where it is sometimes difficult to identify the original subject. The evolution of the octopus image in pottery decoration is an excellent indicator of the changing style. An early copy of a Minoan octopus is more or less accurately represented and its twisting tentacles with detailed suckers randomly cover all of the vase but gradually they become more formal with tentacles painted symmetrically on either side of the body and finally the tentacles become mere lines, impossibly long in relation to the body size and usually fewer than eight are depicted. Eventually, dark bands of varying width become the principal form of decoration and only the space near the neck of vessels is used for pictorial representations.

MYCENAEAN LEGACY

Mycenaean pottery was exported and imitated throughout the Aegean and also in places as far afield as Anatolia, Syria, Egypt and Spain. There is also evidence that Mycenaean potters actually relocated and set up workshops abroad, particularly in Anatolia and southern Italy. Indeed, it may well be that designs of Mycenaean origin introduced into these areas lived on to be re-introduced back to mainland Greece once the so-called Dark Ages that followed the fall of the Mycenaean culture had ended. This three-century decline in all areas of culture but particularly in arts and crafts would, therefore, not be an end but only an interruption in the evolution of Greek culture. Pottery design would once more flower with the geometrically styled pottery of the 8th century BCE. The “new” style owes a great debt to the highly stylized pottery decoration so loved by the Mycenaean people.14 Perhaps the greatest legacies of the Mycenaean age were the stories that were shared in the epic poems, The Iliad and The Odyssey. These will be briefly summarized in the next part of this chapter.

References:

1. Photo by G Da, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_Lions_Gate_of_Mycenae_(13th_century_BC),_Greece_-_panoramio.jpg

2. Photo by Orlovic, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Lions_Gate_detail.JPG

3. Photo by Zde [CC BY-SA 3.0, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lion_Gate#/media/File:Pithos_102972x.jpg

4. Photo by George E. Koronaios, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_entrance_to_the_Tomb_of_Agamemnon_on_October_27,_20 19.jpg

5. Photo by Sharon Mollerus, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Atreus_Tholos_Tomb_(3378349043).jpg

6. Photo by Carlos M Prieto, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Atreus_Tholos_Tomb_(3378349043).jpg

7. Encyclopedia Britannica. “Treasury of Atreus.” Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica. Jul 23, 2008 https://www.britannica.com/topic/Treasury-of-Atreus accessed 12/28/2019 7.

8. Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris, ” Mask of Agamemnon ,” in Smarthistory, November 24, 2019, https://smarthistory.org/mask- of-agamemnon.

9. National Archaeological Museum CC BY 2.0 https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:MaskOfAgamemnon.jpg

10. Photo courtesy of Kathleen J. Hartman. CC BY-NC-4.0 License.

11. Photo by Schuppi, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mycenaean_Cemetery_of_Paleo_Epidavros_-_Findings_4.JPG

12. Photo by Sharon Mollerus, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Amphora_with_Octopus_(3406154155).jpg

13. Archaeological Museum, Nicosia, Cyprus. Photo by Молли, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Arheologicheski-Octopus.jpg

14. Cartwright, Mark. “Mycenaean Pottery.” Ancient History Encyclopedia. Ancient History Encyclopedia, 01 Oct 2012. Web. 09 Oct 2019.