10.4 ILLUMINATED MANUSCRIPTS

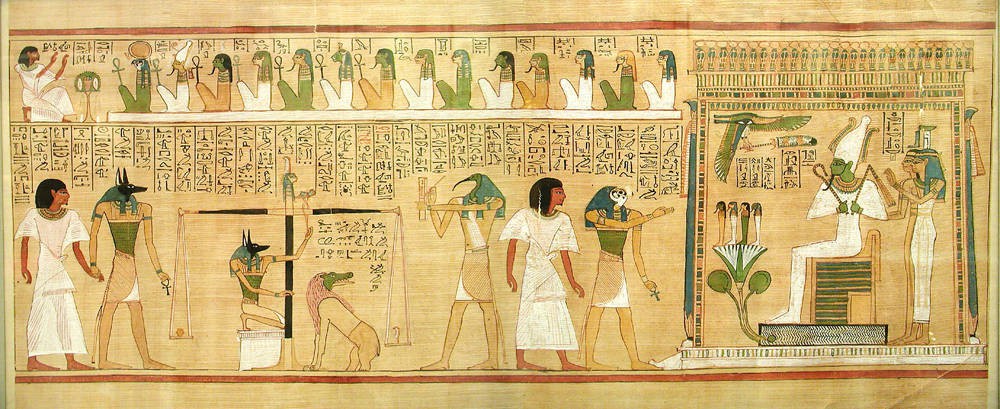

As far as we know for thousands of years of early human history, men did not have the skills to write down their ideas and thoughts and carry them around to read later. It is possible that they inscribed their thoughts on perishable materials, but that would mean that they no longer exist. The earliest illuminated manuscripts that we have are Egyptian papyrus rolls of the 2nd millennium BCE. These are often sacred texts intended for use by the pharaohs in their burial ceremonies, but they also included both painted images of the gods’ interactions with humans and hieroglyphic prayers, hymns, instructions and stories. They discuss the progress of the dead through judgment and the afterlife as the dead person strives to become one with the gods. See image 10.50.

It is difficult for us, who can buy a book for a dime, to understand the high regard that people of the past had for books. As the power of the Christian Church grew, leaders sought ways to transmit information, teach believers, and pay homage to god, the saints, and the wealthy patrons who would buy their work. During the middle ages books were made of vellum, which is tanned, split, and polished hide of sheep, goats, or calves. Some manuscripts might take as many as 500 animal skins, so these books were extremely expensive when we consider that the animals could no longer produce valuable wool or milk products. Until the invention of moveable type in the early 15th century, books were only available for royalty, church leaders, and the very wealthy.

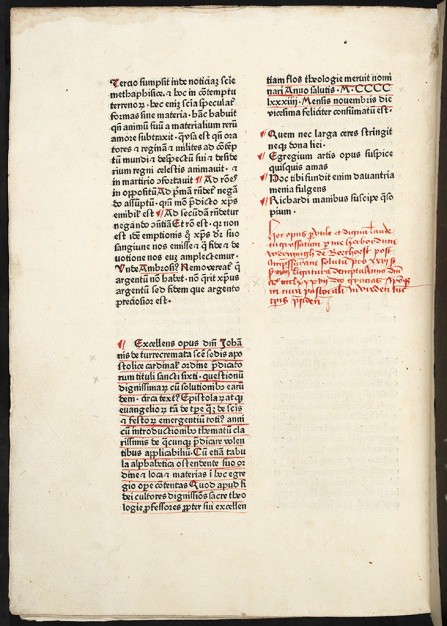

The process to create these treasures began in a scriptorium or workshop, which was usually in a monastery. With the rise of the universities lay artists increasingly took over the creation of these manuscripts. Vellum was slightly translucent and durable, and could be reused if the top layer of script was scraped off and new text written in its place. Once the vellum was tanned and ready the pages were laid out with ruled lines. Writing was done by literate men or women, called scribes, who copied texts onto the vellum in black ink. Scribes left spaces to be filled in with titles and chapter headings written in red ink. These were called rubrics, a Latin word for the red earth pigment used to make the ink, and the artists were called rubricators. Normally rubricators do not sign their work. They may underline text, draw beginning letters in a larger and more elaborate font, and add descriptive text. See image 10.53.

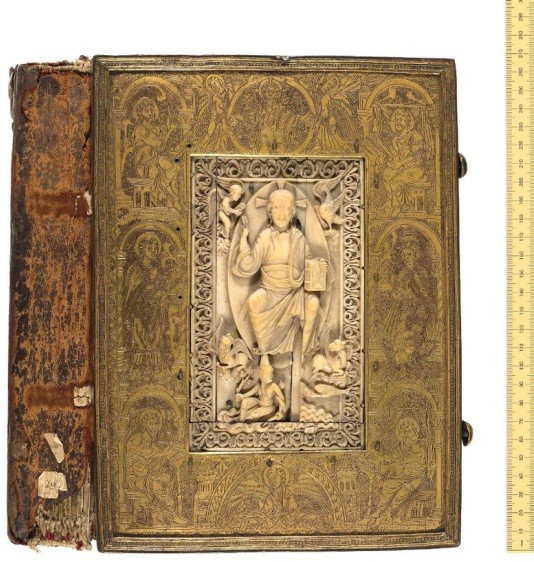

Other artisans then decorated the manuscripts with small pictures. Sometimes pages were gilded with gold or silver, and then the miniature images were painted using animal, vegetable, and mineral extracts. Paint was gouache, an opaque mixture of pigments and binder like modern poster paint. The most common pigment was a red oxide of lead, called minimum and anyone who worked with minimum was called a miniator. The small size of the manuscript images led to the present use of the word miniature to mean anything tiny. Books were bound in a heavy cover of precious metals or carvings and often embellished with gems. See image 10.52.

Illuminating manuscripts was an act of piety by the faithful. All faithful Benedictine houses performed this service. Clunaic houses fostered it diligently. A monk skilled in his craft would not have been content to copy letters all of his life, so he might graduate to painting miniature images in the small spaces and margins in the book. Perhaps at first he or she drew a few little pen drawings or an elaborate initial at the beginning of a paragraph. The development of this art may have been a small compensation for the tedious life of a monk. A monk or nun might spend a lifetime creating a single book.

Many different types of holy manuscripts existed. They were often used in religious ceremonies and were commissioned by princes and church dignitaries. The book might be placed on the neck and shoulders of the person being invested in a new church or political office to show that God approved of their new calling and was giving His blessing.

There many types of holy texts including:

- Psalters- the Psalms of David from the Old Testament

- Books of Hours –private prayer books devised for the use of a specific person

- Bestiaries-facts and fables about animals

- Collections of the lives of the saints

- Missals and Sacramentaries from the Bible for use in the Mass

- Antiphonaries and Lectionaries- to be read aloud

Manuscript illumination was the model for many other types of art that sprung up during this time. Larger versions of the miniature stories were translated to stained glass windows. They also became models for murals and other large paintings on the walls. Some of the same stories can be seen in the tympanums, trumeaus, and other ornate sculpture that filled the cathedrals and churches across the Christian world.

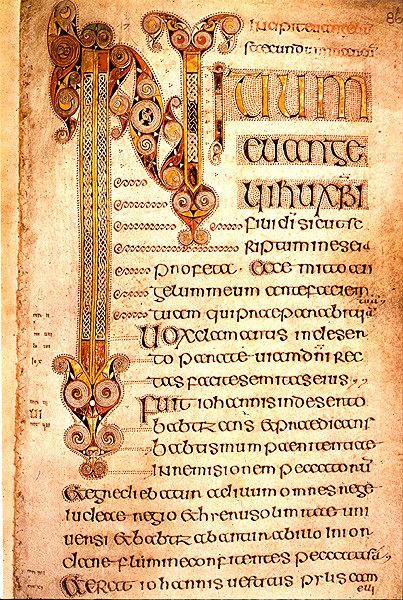

Some of the earliest examples of illuminated manuscripts in the Christian medieval world had strong influences from the wandering tribes of the north. Missionaries sought to stabilize and subjugate the tribes and convert them to Christianity, and yet they brought with them their artistic influences. One of the most important examples is the influence

of the Irish culture. From 400 CE to 750 CE the British Isles sank into conflict and confusion, but monasteries were established in Britain, Italy and Germany. This encounter between Irish and Germanic Christianity resulted in Hiberno-Saxon manuscripts. These are examples of syncretism, as is discussed in the cultural values section of this text. The Book of Durrow is an example of this type of art. Notice the intricately twined decoration on the first letter of the text. Compare the twisting shapes in the manuscript to the clasp of a purse found in a burial at Sutton Hoo. Notice the intertwined filigree.

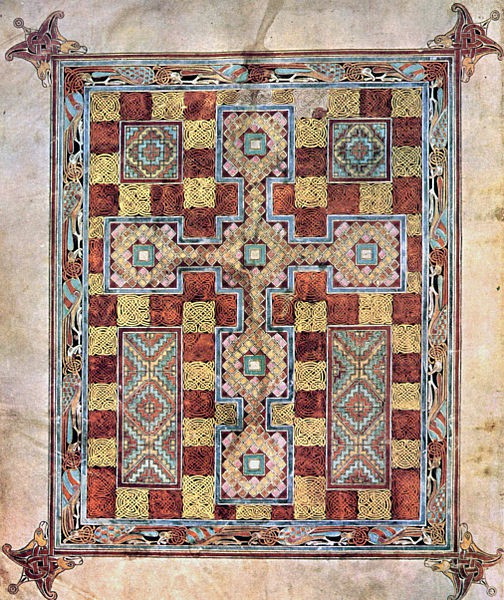

Another example from this same culture and the same place is the Lindisfarne Gospel, made in the late 7th century in a monastery off the coast of Northumberland. It is 13×10 inches and is now housed in the British Library in London. It is still complete with prefaces, canon tables, and commentaries. In the back of the book is a list, compiled by Aldred, prior of Lindisfarne, which is a history of the efforts of many predecessors who made the book. The list says that it was written by Eadfrith (698-721), Bound by Ethelwald, adorned with ornaments of gold and jewels by Billfrith. It was glossed (translations written on the page) in English by Aldred. Each book was preceded by a carpet page with an intricate cross and abstract tiny animal designs. See image 10.55.

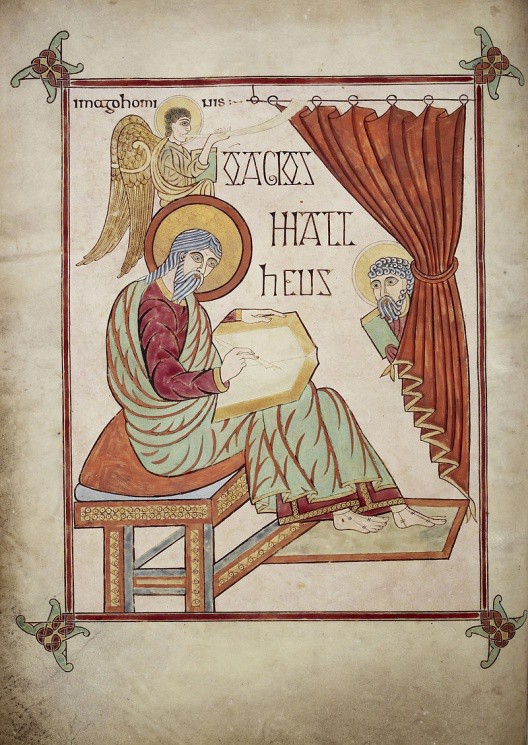

Often the manuscripts had an image before the beginning of each book. In the Lindisfarne book, Matthew sits on a pillow on a wooden stool with the scriptures on his lap and a goose feather quill pen in his hand. His name is written in Greek. Above him is his symbol, an angel blowing a horn to announce the coming of the gospel.8

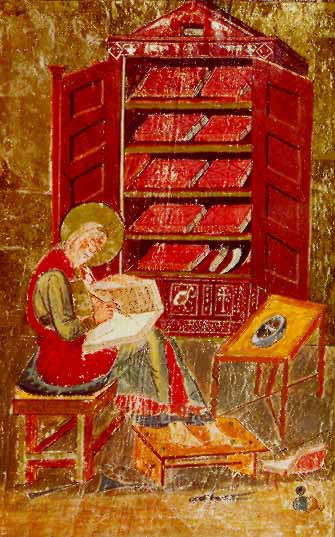

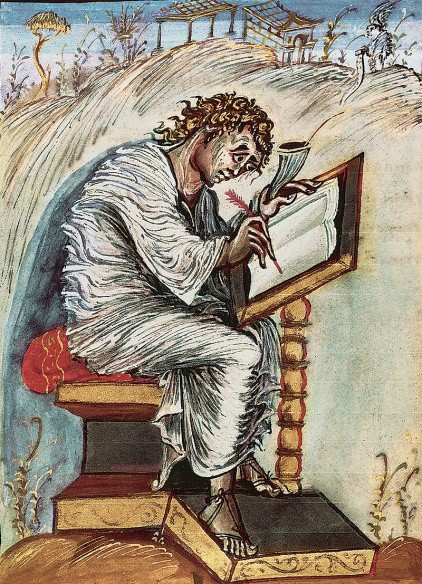

Compare the Ezra page from the Codex Amiatinus (see image 10.58) which was penned at almost the same time and in a place very close geographically to the Lindisfarne gospel. Note how similar they are. There is speculation that the persons writing both of these works were looking at the same source. But take note that Matthew is much flatter and there is no real attempt to create space. Note that the lines of his clothing are hard and there is no modeling or shading. The differences could be based on the flat, decorative style from Hiberno-Saxon culture and the more natural style found in Roman influences.11

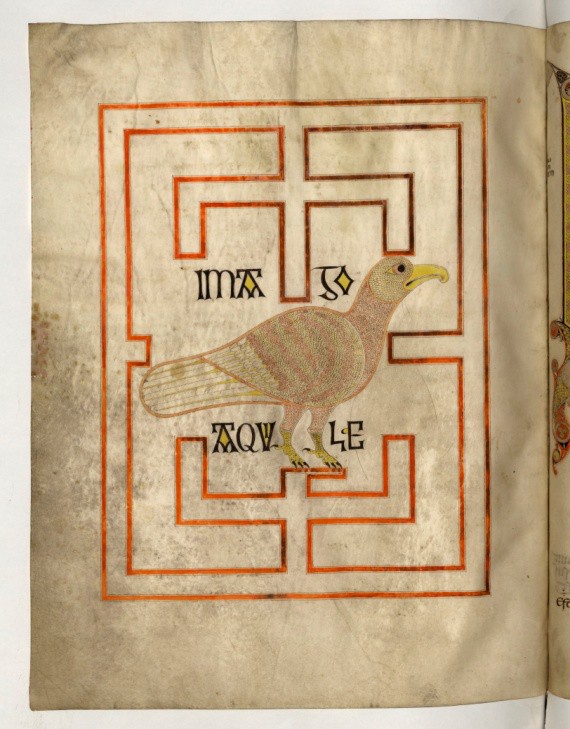

Notice the clean lines of the St. Mark page and the St. John page from the Echternach Gospels, written in about 700 CE. See images 10.59 and 10.60. The manuscript was probably taken by Willibrord to the monastery at Echternach which is now in Luxembourg, when he founded it and may have been used in missionary efforts as he traveled. The lines used by this artist are simple and straight rather than the writhing, tangled snakes we just saw in the Lindisfarne Manuscript. It looks as though it has been drawn with the aid of a compass. The rectangular background pattern which controls the apostle’s ascent through space also binds them to the confines of the page.

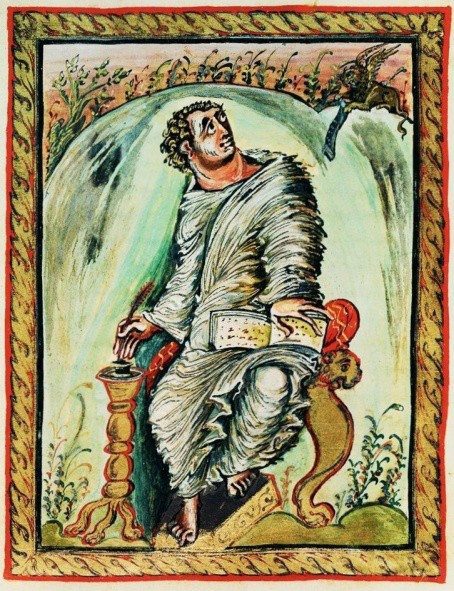

The gospel of Ebbo, also known as the Book of the Gospel of the Archbishop of Reims, was created between 816 and 835 CE in Hautvillers, France. See images 10.61 and 10.62. It is 10 ¼ x 8 1/4” and is tempera on vellum. These images are packed with an energy that amounts to frenzy. The folds of their drapery writhe and vibrate. Their hair stands on end. The landscape in the background almost rears up. Matthew appears to be hastily writing the inspiration he is receiving, his body tense, his shoulders hunched, his head thrust forward. Their symbols, taken from the Book of Revelation, are in the upper right corners: Matthew is the man with the horn announcing the gospel and Mark is the lion.

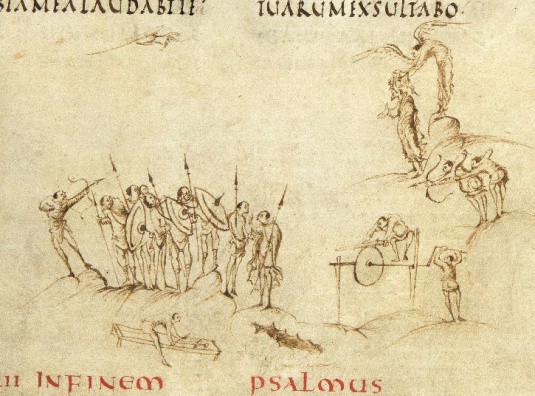

The Utrecht Psalter has much in common with the Gospel of Ebbo, and was also made in the monastery of Hautvillers near Reims in about 830 CE. See images 10.63 and 10.64. It is drawn rather than painted and may have been created in a monastic scriptoria that was not supported by a wealthy court. The psalms are not easily translated from written language to pictorial language because they are poetic verses intended to be sung during religious services. The artist could solve that problem in several ways: he could repeat the main character in multiple positions on the page, choose a single instant from the psalm to represent the general message, or illustrate key words or phrases and somehow tie them together. The Utrecht artists chose to depict multiple groups of words depicted on the page for each psalm. The 63rd Psalm for instance shows the hand of God: “thy right hand upholdeth me”. The image of the 149th Psalm shows an organ: “Praise ye the Lord with a new song.”16

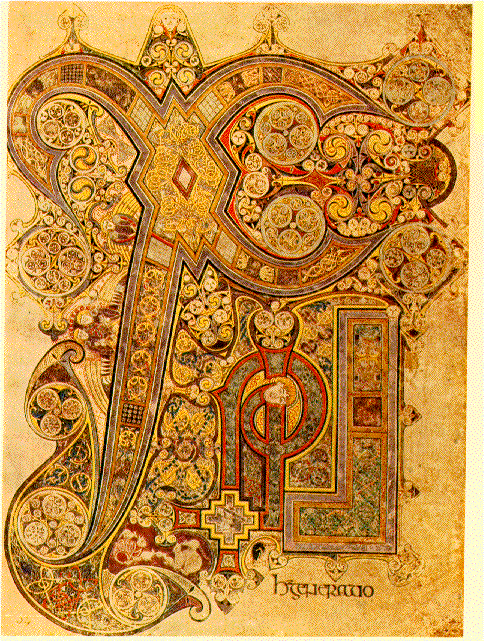

The Book of Kells is the most richly illuminated Celtic manuscript preserved to our day. It was created in the 8th century and was saved from Viking attack in 802 CE when it was carried to the Irish monastery of Kells. It is believed that many artists worked on this masterpiece.

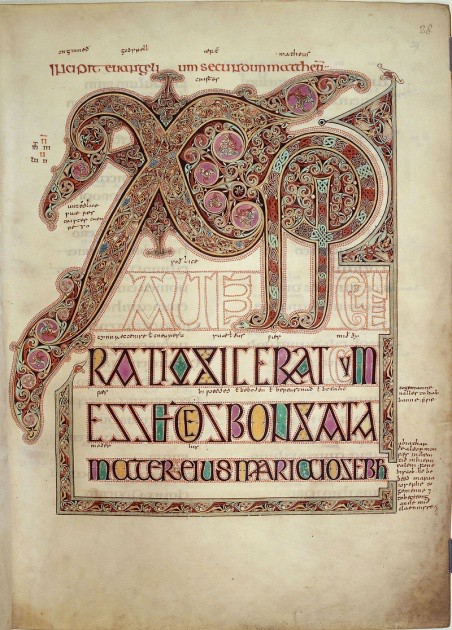

Image 10.65 and 10.66 are incipit pages, meaning that they are the first few words of a chapter in the scriptures. The Chi Rho page is abbreviated text for “Christi autom generatial” meaning The Book of the Generations of Jesus Christ. The letters are subdivided into panels filled with interlaced animals and snakes as well as spirals and knots. In spite of the intricacy, it is possible to trace every line as a single thread. To the right of the Chi’s tail (image 10.67) two cats pounce on a pair of mice as they nibble on a Eucharistic wafer, an allegory referring to the fight between good and evil.

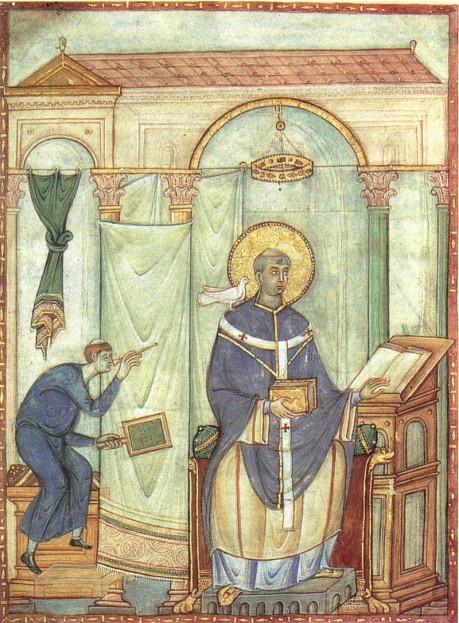

The Registrum Gregorii is a collection of letters written by Pope Gregory the Great. The book was compiled in 983 in Winchester and illuminated by the “Gregory master”. It was presented by Archbishop Egbert to his cathedral and shows Pope Gregory sitting on a golden throne, working at his desk. The Holy Spirit in the form of a dove sits on his shoulder providing inspiration, while a clerk peeks through a curtain. Perspective is not linear and it is difficult to tell whether he is in the building or outside. See image 10.68.

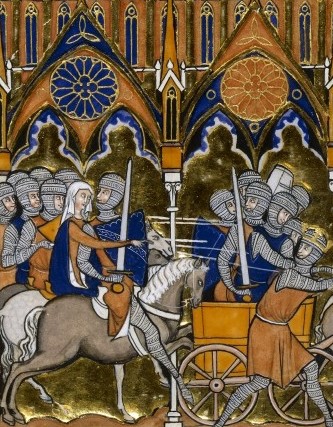

The Psalter of St. Louis is a late manuscript that was painted by an unknown miniaturist between 1250-1270. It is parchment with ink tempura and gold and was made for Louis IV of France by craftsmen who were associated with the builders of the cathedral at St. Chapelle in Paris. It may have been made by the same artisans who made the stained glass windows.

WOMEN IN MONASTIC LIFE

Gender roles during this time reflected a patriarchal society. The Christian religion generally taught that wives were to submit to their husbands, and the men who wrote much of the religious texts often thought of women in terms of weakness and temptations to sexual sin. “You,” an early Christian writer had exclaimed of women, “are the devil’s gateway…you are the first deserter of the divine law…you destroyed so easily God’s image, man…”26 The warlike values of the aristocracy meant that aristocratic women were relegated to a supporting role, to the management of the household. Both Roman and Germanic law placed women in subordination to their fathers and then, when married, to their husbands.

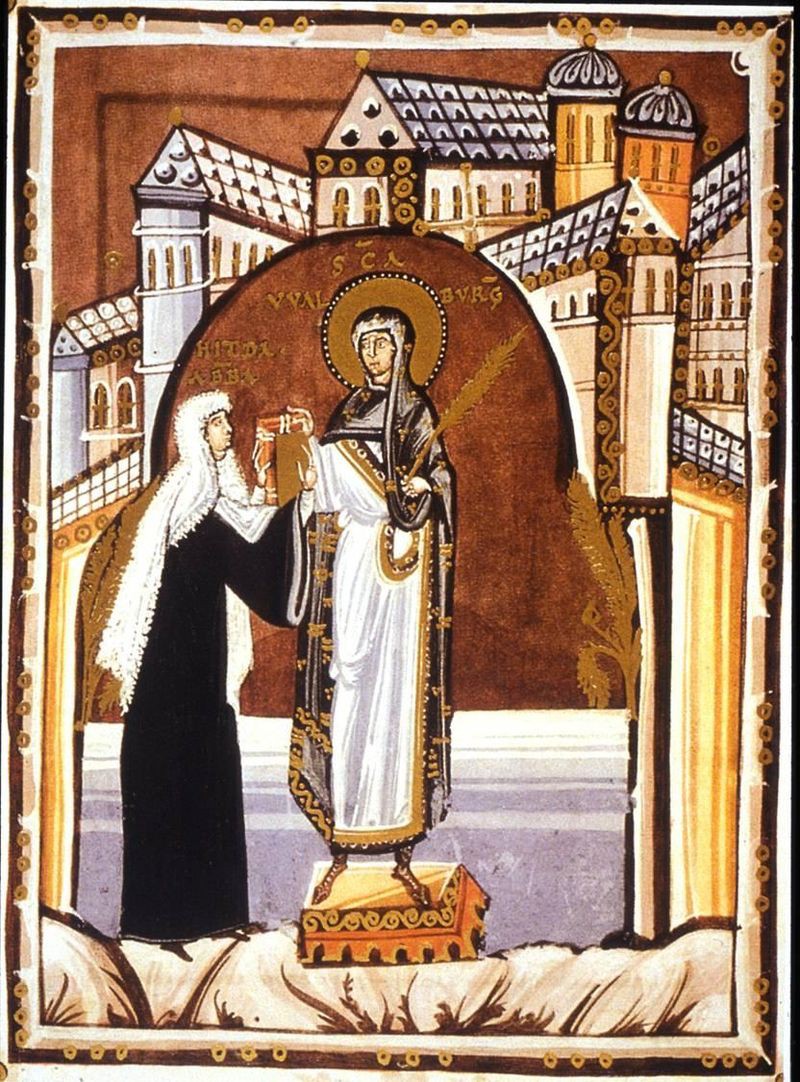

However, women did enjoy certain rights. Although legally inferior to men in Roman Law (practiced in the Byzantine Empire and often among those peoples who were subjects of the Germanic aristocracies), a wife maintained the right to any property she brought into a marriage. Women often played a strong economic role in peasant life, and, as with their aristocratic counterparts, peasant women often managed the household even if men performed tasks such as plowing and the like. And the Church gave women a fair degree of autonomy in certain circumstances. We often read of women choosing to become nuns, to take vows of celibacy, against the desires of their families for them to marry. These women, if they framed their choices in terms of Christian devotion, could often count on institutional support in their life choices. Although monasticism was usually limited to noblewomen, women who became nuns often had access to an education. Certain noblewomen who became abbesses could even become powerful political actors in their own right, as did the Abbess of Hitda in the 11th century.

The Abbess of Hitda is shown in image 10.72 presenting an expensive book to St. Walburga, the female patron saint of Meschede, a large female monastery in the diocese of Cologne, Germany. This manuscript was created in about 1000-1020 CE and is in Darmstadt, Germany. The Abbess belonged to a group of women who were the daughters and nieces of the aristocratic leaders. Since she is presenting the codex to the saint, this shows her position and her authority. She has the right to be in the presence of the saint and to represent the monastery. This means she has more power than the male clerics and leaders who lived and worked with this community of sisters.27

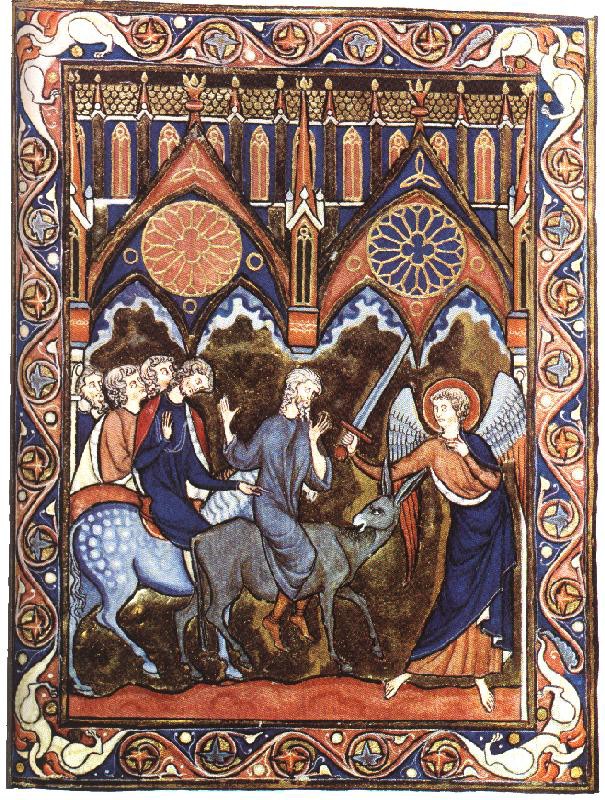

(See image 10.73) The Storm on the Sea of Galilee shows the artist’s gift of storytelling. The boat forms a diagonal line from upper left to lower right, the sail is whipped by the fierce wind, and the boat and its passengers plunge through the sky and the water, even going over the outer frame of the manuscript page. Note the agonizing expressions of the gold haloed apostles looking toward heaven and trying to awaken Christ. He sleeps on; the long folds of drapery draw our eyes to him. This work was not necessarily created by women artists, but it was women who most likely paid for it and made a gift of it to the saint protecting the women of the monastery.

One of the most important women in monastic life was Hildegard of Bingen. She was the Abbess of the monastery at Bingen, overlooking the Rhine River in Germany. Hildegard was born in 1098 into a noble family and became a Benedictine nun at the age of 18. She was an artist, author, and composer and was said to have had many visions beginning at the age of three. She often wrote letters to people who asked her for advice and she talked with popes, emperors, and other leaders of the church. She wrote letters about natural science, the treatment of diseases, and music. Image 11.74 is a facsimile of a page showing Hildegard’s receiving inspiration for her collection of revelations called Scivias “Know the Ways of the Lord” which were accepted as divinely inspired by the church. The original image was lost during World War II.30

Attribution:

Berger, Eugene; Israel, George; Miller, Charlotte; Parkinson, Brian; Reeves, Andrew; and Williams, Nadejda, “World History: Cultures, States, and Societies to 1500” (2016). History Open Textbooks.

References:

1. Photo by Hunefer, John Bodsworth, Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:BD_Hunefer.jpg

2. Flickr’s The Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File: Rubricator%E2%80%99s_signature _in_ red_ ink. _(5353140762).jpg

3. Bodeleian Libraries, Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bodleian_Libraries,_Manuscript_ of _ the_first_two_Gospels_only_Matthew_ and_John.jpg

4. Dsmdgold at English Wikipedia, Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File: BookOfDurrow Begin Mark Gospel.jpg

5. Photo by Geni, CC BY-SA 4.0. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sutton_hoo_purse_lid02017.JPG

6. Photo by anonymous, Public domain.https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Meister_des_Book_of_Lindisfarne_002_2.jpg

7. Photo by anonymous, Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:LindisfarneChiRiho.jpg

8. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TYds0dsratI

9. Photo by British Library, Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:St._Matthew_-_Lindisfarne_Gospels_(710-721),_f.25v_-_BL_Cotton_MS_Nero_D_IV.jpg

10. Photo by monks, Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ezra_Codex_Amiantinus.jpg

11. https://smarthistory.org/codex-amiatinus/

12. Photo by Gallica Digital Library. Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File: Evang%C3%A9liaire_ d%27 Echternach_-_BNF_-_f176v_aigle.jpg

13.Photo by the Yorck Project, Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File: Meister_des_ Evangeliars_ von_ Echternach_001.jpg

14. Photo by Giraudon/Art Resource, Public domain. Bibliotheque municipal de Epernay. https://commons.wikimedia.org/ wiki/File:Saint_Matthew2.jpg

15. Photo by Sailko,Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File: Vangeli_di_ebbone_ (evangelista_marco) ,_ epernay,_Biblioth%C3%A8que_m unicipale,_Ms._1_f_18_v.,_20,8x26_cm,_ante_823.jpg

16. https://smarthistory.org/utrecht-psalter/

17. From Utrecht University Library, Public domain.https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File: Utrecht_Ps63_ (cropped)_ (cropped2).jpg

18. Ibid, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Utrechts-Psalter_PSALM-149-PSALM-150_organ.jpg

19. Photo anonymous, Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Book_of_Kells_ChiRho_Folio_34R.png

20. Photo anonymous, Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:KellsFol130rIncipitMark.jpg

21. Photo anonymous, Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Book_of_Kells_34r_-_Katzen_ und_ Maeuse.jpg

22. Photo courtesy of Trier Stadtbibliothek, Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File: Registrum_gregorii, _san_gregorio_magno_ispirato_dalla_colomba,_983_mi niatura,_treviri_stadtbiblithek,_19,8x27_cm.jpg

23. Photo courtesy Conde Museum, Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File: Meister_des_Registrum _ Gregorii_001.jpg

24. Photo courtesy of Bibliotheque Nationale de France, Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File: D%C3%A9bora_et_Baraq_BnF_Latin_10525_fol._47v.jpg

25. Photo courtesy of Web Gallery of Art. Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:13th-century_painters_-_Psalter_of_St_Louis_-_WGA15850.jpg

26. Tertullian, On the Apparel of Women, 1:1.

27. https://inpress.lib.uiowa.edu/feminae/DetailsPage.aspx?Feminae_ID=34059

28. Photo courtesy StudyBlue, Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hitda_Codex_-_dedication_ miniature_f6r_-_DarmBib_1640.jpg

29. Photo anonymous, Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hitda-codex.jpg

30. https://www.franciscanmedia.org/saint-hildegard-of-bingen/

31. Photo anonymous, Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hildegard_von_Bingen.jpg