4.5 The Trojan War (or The Iliad)

The Trojan War, once believed to be fictitious, was one of the most important events in the History of Greece. The story of this war, which took place sometime between 1150-1250 BCE., was captured in two epic poems, and was later put into writing sometime between 650 and 750 BCE when the Phoenicians brought the alphabet to Greece. The Iliad, supposedly written down by Homer, is set during the last nine months of that war. This is the story that would be retold for thousands of years and would teach many generations about the cost of war, the need for honor and loyalty and the history of the Mycenaean culture, which fell shortly after this engagement.

The war began because Zeus’ mother, Gaia, asked her son to reduce the numbers of mankind as the race was disturbing Gaia (Mother earth) with their digging of mines and other such things. A plan goes into action through a young man who was completely ignorant of the part he would play in the destruction of two cultures. Paris, the son of King Priam of Troy, had been abandoned as a child due to a prophesy that the babe would be the cause of the end of Troy. In typical Greek mythic fashion, Paris was not really abandoned but instead, was raised by a shepherd and later became embroiled in a beauty contest between three goddesses. This contest was part of Zeus’ plan to relieve his mother of her pains. Paris chose the goddess, Aphrodite, as the winner, because she had promised him a prize of the most beautiful woman in the world. Alas, she failed to tell him that the woman, Helen, was already married to a king named, Menalaus.

There are clear lessons to be learned from this part of the tale. Be careful what you ask for is one. Another is that things are not always as they seem. The constant interference and interruptions by the gods, also reminds the listener (originally this would have been recited out loud) that the gods should never be slighted for they had power to alter men’s lives, if not their fates.

To make things more challenging, while they had been vying for Helen’s attentions, every Greek male of marriageable age had vowed to protect her and to honor whoever won her. As such, they were duty bound to get her back once Paris had taken her away from Menelaus. The king had been temporarily out of town at the time of the abduction. The former shepherd and now the recognized son of Troy (he came to Troy and was so amazing that he was recognized as royalty) took Helen across the Aegean Sea, to the city he was now a part of again. This situation was not only in accordance with Zeus’ plan but was also a result of Menelaus forgetting that he had promised a sacrifice to Aphrodite, if he were lucky enough to win Helen’s hand. He had forgotten that promise.

The listener is reminded that it is never wise to anger a goddess! There is also reference to Paris having committed the most horrid of sins. It was required of a good Greek that he take in supplicants, like Paris, who showed up at Menalaus’ door. To treat such hospitality so rudely as to steal a man’s wife, defined Paris as a scoundrel who deserved whatever he got. Every great story needs a villain, and for the noble Greek, being a coward was villainess on its own.

So, off to war go the Greeks and all of their allies. It could easily take year to travel along the coastlines from Mycenae to Troy. Navigation that allowed one to cross a sea was not yet available. The siege lasted ten long years. Books two through twenty-three of The Iliad are dedicated to a four-day period of time when the most important Achilles, an Achaean warrior who had been prophesied to be the champion upon whom winning the war would depend. An Achaean was a member of a group of the Hellenes or as we now refer to them, Greeks. Achilles had a conflict with his king, Agamemnon. Menelaus and his brother, Agamemnon ruled together, as it is assumed was the practice at some time in Mycenae, and which would be the practiced in the same region when Sparta ruled it.

Because he had to return his own prize, the Theban woman, Chryseis, King Agamemnon took away the war prize that Achilles had earned for himself, a woman named Briseis from Lyrnessus. In a culture where honor was everything, this left Achilles deeply insulted. Because of this disagreement over a war prize, Achilles withdrew from the battle, putting the entire Greek army in jeopardy. At first all went well, but when things got worse, Patrocolas, close friend and relative of Achilles, put on his famous war mate’s armor, hoping to raise the moral of the troops. Mistaken for Achilles, he was killed by Hektor, the eldest son of the Trojan king, Priam. This is one of many warnings against the cost of pride that can be found in The Iliad. Because of his pride, Achilles lost someone dear to him. Because of his pride, King Agamemnon almost lost the war.

Having turned his anger on Hektor, the first son of Troy and the city’s champion, Achilles decided to get his revenge on the killer of his friend. When Achilles’ rejoins the war the tide of the battle is turned. He teaches the listener another lesson when he inappropriately drags Hektor’s dead body around the walled city. A touching scene where the old king Priam sneaks into the Greek camp to ask for his son’s body back reminds the listener that there are expectations of respect between enemies. It is also important to realize that there was a large Greek settlement in Troy at the time that it was attacked. In many ways, the Greeks were fighting Greeks. Finally Achilles, perhaps embarrassed by his own behavior, allows Priam his request and holds off on the battle while the appropriate funeral games are played. The games determined who would inherit the deceased warrior’s weapons and other belongings. The listener would sense the validation of appropriate social behavior in this tale.

After Achilles is killed by Paris’ arrow it is through sneakily gaining a tactical advantage that the war is finally won. The Iliad does not go as far as telling about the Trojan Horse filled with Greek warriors that is rolled into the city by its inhabitants. They thought that they had driven the Greeks away. It is alluded to, however, so that at the end of The Iliad, the listener knows how the war began, how it was fought and how it ended.

Some scholars believe that The Iliad was initially constructed to validate the Mycenaean campaign against Troy. Since the only version that lasted until it was written down did not come into being until sometime in the 8th century BCE. One can only guess at the intent of the story when it originated. There is no doubt, however, that it did educate Greeks about how to act in their world and in their society. The Iliad became a treatise on proper and improper behavior. It taught religion, social expectations and moral lessons to many generations who followed in the footsteps of those “original Greeks,” the Hellenes, of which the Mycenaean culture was part.

THE ODYSSEY

The Odyssey is the story of the hero Odysseus returning to his home in Ithaca on mainland Greece. It is executed in a different style than The Iliad. While the Iliad is about public heroism, The Odyssey is about private heroism. It is told in first person and is filled with supernatural creatures that probably stand in for foreign cultures around the Aegean Sea. The tale is about travel and exploration and is filled with disguised history about the strange and wonderful things that one may come upon when away from home. More than anything, however, The Odyssey is about the need to be at home with family. This tale demonstrates the cost of war in a new way, focusing not only on the heroes but also on the heroism of a wife, who never wavers in her loyalty to her husband.

Odysseus also must learn the cost of pride, which nearly causes him to lose everything and does cause him to lose his ship and all of his men. The long journey begins because he is too prideful about his brilliant idea to construct a wooden horse in order to trick the Trojans into losing the war. Later he taunts the son of Poseidon, a Cyclops that ate a few of his men, and he suffers for years because of it.

This would be a great choice of tale to tell on a cold and stormy winter’s night when fantastic things can be easily imagined. As in The Iliad, there are moral lessons and many references to customs such as a widow being married to the best suitor, rather than being allowed to rule on her own. With her goes the kingdom and all of its goods. Likewise there is a focus on the need for hospitality as Penelope, Odysseus’ wife, must entertain the suitors at her husband’s expense. The suitors take unfair advantage of the hospitality, however. Like Paris before them, they pay the price for this rudeness.

When Odysseus finally makes it home, Athena disguises him as an old man and in that form he wins his wife in an archery contest and with his son, now grown. He then kills all of the hangers-on that have been plaguing his loyal wife and then makes sacrifices to the gods to atone for his prideful behavior. Unlike most of the heroes of The Iliad, Odysseus lives happily ever after.

FROM THE AR TO THE GEOMETRIC AGE

Traces of the Mycenaean Civilization disappear shortly after the time of the Trojan War. If Homer is correct in telling us that the war lasted ten years and that many did not return or returned as long as a decade later, it is no wonder that the Mycenaean culture faltered. There is discussion in The Iliad of the ships leaving the Trojan shore. There is no discussion of them leaving with great piles of loot, other than slaves. Perhaps the great adventure was too expensive for the culture to bear.

In any case, the two king system of the Spartans, who ruled much later in Southern Greece, never allowed both kings to be at war at the same time. It would not be until the Peloponnesian war, in the 5th century BCE that Greeks would again attempt such a bold venture. That venture, the attempt to build an Athenian Empire, came to its conclusion much like the first one. In the end, the war was far too expensive to benefit Athens in the long term.

With the failure of the political structure the grand building program of Mycenae ended. Burials were no longer done in grand tombs. Palaces and fortifications were no longer built. The fact that the culture was revived after such a long period of decline indicates that although there is little evidence of it, the resilient Greeks continued on, holding on to their stories of the past in order to learn from them.

It is also likely that many of the ideas that Mycenaean culture shared with the world may well have come full circle and returned to the region as the culture there began to grow and prosper again. There are far too many similarities between the early cultures of the Aegean Sea and the later cultures of the same area to think that there is not a strong connection between the groups.

Following the fall of Mycenae people grouped themselves into tribes. Over time the tribes became more sophisticated and the people became more settled. Limited agriculture began again and the goddess Demeter looked out for it. The pantheon of gods not only survived but would eventually expand as new ideas flowed back into the mainland. For many centuries, however, this slow growth was not accompanied by lasting building projects or monumental sculpture. As such, this period of time (c 1150-750 BCE.) is often referred to as “The Dark Age.”

GEOMETRIC PERIOD

Pottery

After the fall of Mycenae, around 1100-1150 BCE., mainland Greece sunk into a Dark Age. Governmental structures crumbled, trade slowed and large architectural edifices ceased being built. Eventually, between 900 and 750 BCE., stylized pottery, resembling the pottery made by the pattern-loving Mycenaean culture reemerged. It was often more abstract than the earlier Hellenic style and it shows signs of Egyptian influence. Much like the Geometric Period sculpture, the images on pottery reflect a growing sense of Greek identity as well as reflecting the past on which that identity was being built. Work from the period also incorporated ideas from the world around the creators.

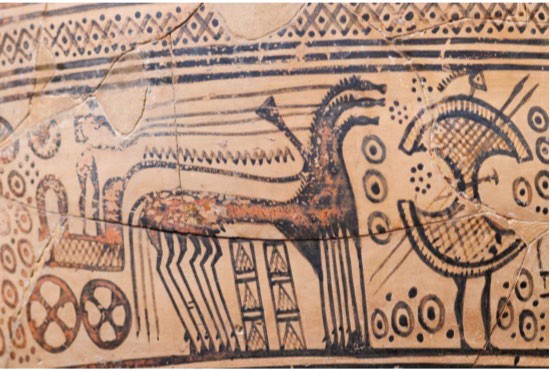

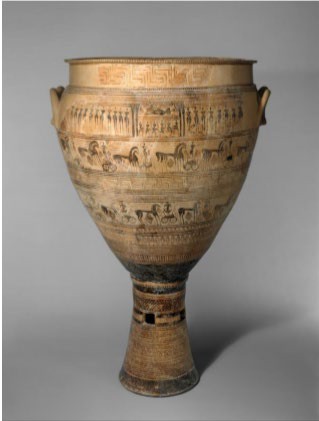

Note the geometric patterns on this shard from a large krater, which is a jar or vase with two handles used to mix water and wine. Kraters were used to cleanse water by adding alcohol to it, so that it was safe to drink. These kraters are some of the best artifacts that have been left to science from the Geometric time period. The krater includes emblems of horses and a warrior. Like the sculpture of the period, the figures are symbols rather than natural renderings. This krater was probably the grave marker of a warrior. Note the horses pulling the chariot into battle. A warrior leads the group but is only indicated by a shield with a head and legs. Size is unimportant as the leading figure is twice the size of the charioteer. No distinction is made between the three horses. The depiction of three heads and twelve legs is sufficient to show how many there are. Notice, that much like Minoan pottery, every space is filled if not by figures, by abstract designs.

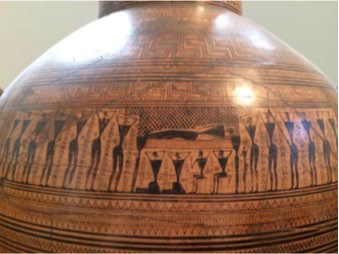

Monumental kraters and amphorae were made and decorated as grave markers. Kraters were large two handled storage jars with narrow necks that were sometimes tapered to a point at the bottom and were used to carry wine or oils. The most famous examples of this art use a technique called horro vacul, in which every space on the vase is filled with imagery. Kraters, sometimes six feet tall, marked male’s graves. Female graves were marked with amphorae.

One of the Dipylon kraters in the Metropolitan Museum is 43 inches (110 cm) tall and has a circumference of 25.5 inches (65 cm). The monumental vase is hollow, with a hole at the bottom, indicating that it was not used as a mixing bowl like regular kraters. It is possible that the krater’s intended use was to accommodate the ritual offering of wine to the deceased. Clearly a krater with a hole intentionally made in the bottom was intended as a ritual object rather than a practical one. This demonstrates that the krater was made specifically as a funeral object rather than reused as one. Ritual, then, is an important part of the death experience.

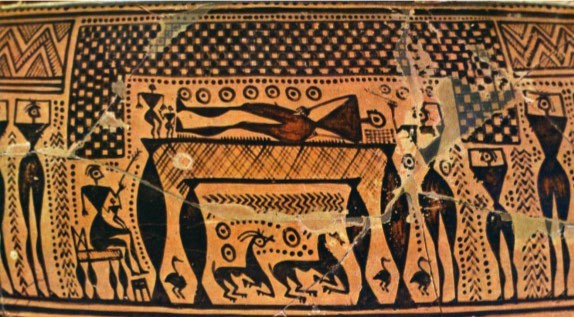

As has been mentioned, it is possible that offerings of wine were poured into the krater. In any case, these funeral kraters are some of the best examples of the geometric style. Note the abstract images of what seems to be funeral games and preparation for the funeral pyre on a similar Krater depicted below. These images resemble the games that were played in The Iliad in order to determine who deserved to inherit the weapons, chariots and war prizes (slaves, wives of captors etc.) of the deceased warrior.

Notice the detail below of the top band of the decoration on one of these kraters. There is a procession that carries the dead warrior on a funeral beir which is a stand on which the dead is placed. Below the bier are animals that are to be sacrificed. These customs were discussed in The Iliad and were practiced through the 5th Century BCE. This approach to honoring dead warriors is a long-standing tradition that was clearly passed down from the Mycenaean civilization. As such, this part of the Greek identity remains intact.

The illustrations on these kraters are done in bands, much like Egyptian wall paintings. The images are formal and emblematic, as are Egyptian images of humans in action. These images cannot be read, unlike that seen in Egyptian images. Instead, they were purely decorative, like that seen on earlier Minoan pottery.

One of the biggest differences between the Mycenaean designs and those of the Greeks that followed them is that the geometric design of the Mycenaeans is less organic. The pottery designs of the Geometric Period required careful division of space which resulted in a much more mathematical image. Like the indications of reason seen in Geometric sculpture, reason and proportion determine the look of the geometric designs. Like the Geometric sculpture, the figures have idealistically broad shoulders, possibly indicating a move toward idealism.

It is fairly easy to see how the Geometric Period pottery reflects the identity that was developing on the Greek mainland, as well as how it reflects the past. As technology improved and new ideas began to flow into Greece again, influences from nearby neighbors, such as Egypt become a part of the art. Although there is still a lot to discover about this period in history, much can be learned from a “reading” of the art.

Sculpture

Following the Dark Age brought on by the fall of the Mycenaean culture, a style of sculpture began to emerge that, like the pottery of the time was essentially geometric in nature, rather than naturalistic. Most of the sculpture made during this time (c. 900 BCE – 700 BCE.) was fairly small. They are made of bronze, terra cotta or ivory. The bronze sculptures, often of figures or animals, were created using the lost wax method of casting. The sculpture of this era is essentially emblematic. Individuals are not being celebrated in these images. Instead the ideas presented are more important than naturalistic presentation. In this period the re-development of the Greek identity can be viewed.

Geometric bronzes were often left as a votive object which was left at a religious site as an offering to the gods at such shrines and sanctuaries as Delphi. Image 4.38 an early image of a centaur, a creature that is half horse and half human. Note that he has the body of a man and his backend is horse-like. By the Archaic Period the human legs disappear, being replaced by a horse body with the top of a man in place of the horse’s neck. This image is a reminder that humans have an animal within them. The Greeks tended to define themselves, not by what they were but by what they were not. The human brain raises man above the beasts. It is through reason that man can raise himself to the level of being able to control a large animal.

Many Geometric Period sculptures reflect an interest in music. Image 4.40 shows a man who seems to be playing a type of hand flute. Figures are often seen playing a harp or lyre, much like the Cycladic figures created generations earlier by the folks who lived on the Aegean Islands. Since music is based in reason, this is a great way to celebrate the abilities of the superior human.

Image 4.40 above was probably left as a votive offering at the site of the Olympics, an area dedicated to Zeus. Horse statuettes were often used as offerings to the gods, due to the high value of horses. Horses became a symbol of wealth because of the great expense of keeping them. It is with the aid of the horse that the Greeks succeeded in warfare. As far back as the Trojan War, the elite rode into battle in a chariot, pulled by a horse. Since it is expensive to commission such statuettes, it is likely that only those who were well off could afford to celebrate in this way. As such it is no surprise that a statue of a charioteer was commissioned, supposedly as a votive object.

Notice that that the figure indicates a focus on the head. The shape of the hair creates an arrow, the tip of which is the top of the head. The collarbones and hair frame the head, bringing even more focus to it. The message seems to be that it is the ability to use reason that separates the charioteer from his horse. A small human is able to tame and control a large animal. This is quite a feat and could certainly not be accomplished through brute force and requires the application of reason. A close look at the Charioteer reveals what was important to this culture’s growing identity. He has broad shoulders, so along with his ability to reason, he is ideally strong. The depiction of the figures’ genitalia is quite small. When comparing this to the oversized head, it becomes clear that the use of reason is expected (or hoped) to be able to overcome baser instincts. Geometric sculpture reveals a growing sense of rationalism and idealism. These ideas will continue to develop as the culture moves through a transformation into the Archaic Period.

EASTERN INFLUENCE FROM THE GEOMETRIC PERIOD TO THE ARCHAIC PERIOD

From c.750 BCE to 650 BCE, important changes came to the Aegean Sea and the lands in and around it. Many scholars have referred to this time as the “Orientalizing” period because Egypt and many other non-Western cultures were lumped together under the title, “Oriental.” This is no longer considered accurate or appropriate so the time period will be referred to as one of eastern influence since much of the change came from east of Mainland Greece.

Some of the most important influences in this time came from the Phoenicians. They had developed navigation and as such travelled farther and faster than anyone that came before them. In addition to teaching the world how to navigate the seas, the Phoenicians brought their alphabet to Greece. This alphabet was based on phonetic sounds and a version of it is used in America to this day. This allowed the Greeks to write down their stories, codifying them so that they can still be read today. Below is an image of an inscription on a fragment from a cup. This is a clear indication that writing had arrived on mainland Greece.

Another thing that seems to have come to, or returned to Greece, is the fertility god, Dionysus who came to be associated with the making of wine. Wine was critical to survival as it allowed water to be cleansed without having to boil it. Trees were at a premium by this time in the rocky land. Wine became an important item of trade and in fact was so popular that the pottery that carried it has been found all around the Mediterranean Sea. During this time many of Demeter’s temples were replaced by temples to Dionysus, the hermaphroditic fertility god that taught Greeks to make wine in one of the popular myths. This myth also warned against the danger of drinking too much wine.

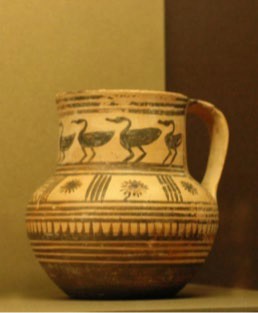

This is an image of a komast dance, which was a part of a procession for Dionysus. Notice that the figures, while not completely natural, are more natural looking than most Geometric images. The figures have taken over the space, with little room left for geometric design. Other changes can also be seen in the decoration found on much of the pottery made during this time. Not only does the decoration begin to incorporate somewhat more natural looking imagery but often the subjects have also changed. The images are sometime of nature rather than of men, funerals and music.

Notice that the birds, although not detailed, are more natural looking than most Geometric Period images. Although the geometry is not left out, it is not the focus of the piece.

This short period of time brought many changes to a Greece that was on the brink of establishing a new identity in the world. Writing, new religious ideas, navigation and new techniques and styles in art arrive with the increase in trade and travel. The Archaic Period that these changes ushered in would establish a new way of looking at humans and at the place of Greece on the world stage.

References:

1. Photo by Metropolitan Museum of Art, CC BY 2.5 https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Geometric_krater_Met_14.130.14_n02.jpg

2. Photo by Metropolitan Museum of Art, CC0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Terracotta_krater_MET_DT263097.jpg

3. Photo courtesy of Kathleen J. Hartman. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

4. Photo courtesy of Kathleen J. Hartman. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

5. Photo by Metropolitan Museum of Art, CC0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bronze_man_and_centaur_MET_DT259.jpg

6. Photo by Walters Art Museum, Public domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=18792877Wikimedia Commons.

7. Walters Art Museum, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=18843678,Wikimedia Commons Public domain.

8. Photo by Zde , CC BY-SA 4.0, https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/a/ab/Charioteer%2C_small_bronze%2C_geometric_period%2C_A M_Delphi%2C_Dlfm404.jpg

9. Photo by Zde, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Fragment_late_geometric_inscriptio_AM_Andros_1200_090528x.jpg

10. Photo by Zde ,CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Attic_poterry,_komast_dancers_580- 570_BC,_Prague_Kinsky,_UKA_80.14,_141917.jpg

11. Photo courtesy Louvre Museum [Public domain] https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Jub_birds_Louvre_CA1930.jpg