8.5 Spotlight on the World of the Spirit: Sant’ Apollinare in Classe

According to popular legend, Emperor Caesar Augustus himself founded Ravenna in the first century CE. In reality, settlement in this part of the Po Valley is even older, reaching back to the Umbrians and Etruscans before it was colonized by Rome in the second century BCE. But the dynamic influence of Octavian on this area is unquestioned. He had built a port facility on these sandy islands at the edge of the Adriatic Sea that could hold, repair, and provision 250 ships. For the next 300 years Ravenna would be Rome’s main naval base for the eastern Mediterranean.

Civitas Classis, later known as Classe, was a satellite town 8 km south of Ravenna. In Latin the word “classis” means “fleet” and here, in the days of Octavian, it was the home of some of the dock workers, sailors and tradesmen from the port of Ravenna. It was also situated on marshland and shared similar land subsidence challenges. By the fifth century CE the port at Ravenna had gradually silted up and the Adriatic Sea had receded, leaving Classe as the major commercial port for the Emilia-Romagna region. Having a claim to Octavian’s fame a reproduction of his famous statue was placed in front of the local basilica of Sant’ Apollinare in 1953 [image 8.89].

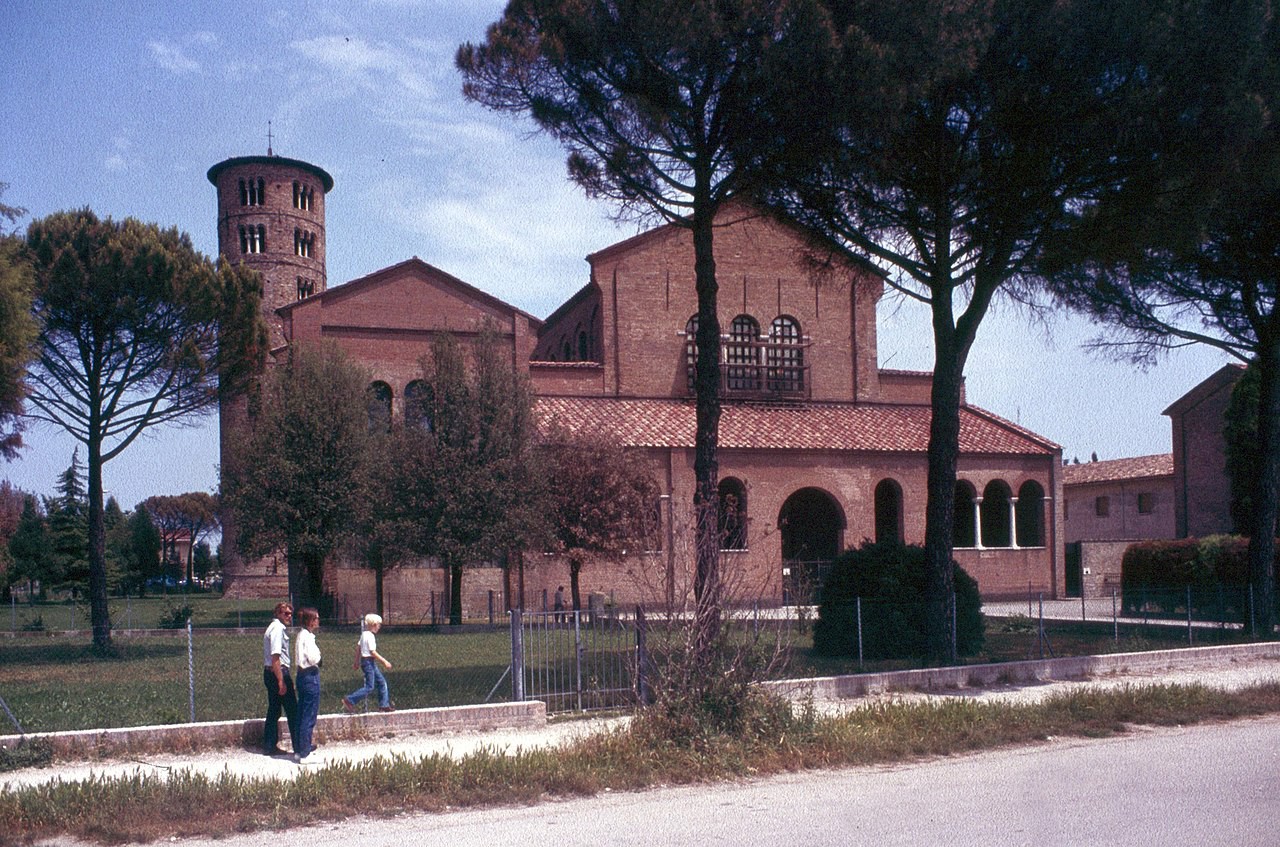

In between the two cities, as well as along the coast, were sand dunes and cemeteries. The burial grounds were properly outside the city of Ravenna, and it was in one of the many Roman-era cemeteries that the first-second century Saint Apollinare, the first bishop of Ravenna, was interred. In the sixth century a church was built over the presumed holy ground. The basilica of Sant’ Apollinare Nuovo in Ravenna (constructed 493-526; dedicated to Sant’ Apollinare in 856)2 and the basilica of Sant’ Apollinare in Classe (built 533-536) both pay tribute to the same saint. The two churches compliment and complete each other. The Ravenna basilica promotes the value of idealism with magnificent nave mosaics while the apse of the Classe basilica shines a spotlight on the mystical world of the spirit.

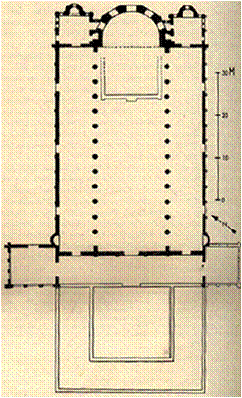

Several conventions that were standard in Early Christian basilica churches, and remain common in future Romanesque and Gothic churches, are to be observed at the basilica of Sant’ Apollinare in Classe [images 8.90-8.94]:

- The orientation of the traditionally-shaped basilica is toward the east. (An east-facing axis was typical of churches until the modern period. If topographic circumstances prohibited an east-facing apse, the altar would still point to the “Liturgical East.”)

- A strict horizontal axis leading toward the apse was as essential in a basilica as the east-facing orientation.

- The basilica originally had twin towers on the north and south ends of the narthex. These were sometimes known as the Peter and Paul towers, or at other times they were named in recognition of Bethlehem and Jerusalem. Here, the rectangular north tower remains from the original sixth century construction; the south tower is only remembered in the original plans [image 8.92].

- As seen at St. Paul’s Outside the Walls in Rome3, a quadraporticus was frequently located in front of a basilica. At Sant’ Apollinare in Classe a modern road has been constructed along the former edge of the quadraporticus.

- A splendid cylindrical campanile was added to the building before the year 1000. The bell tower was useful for sounding the canonical hours. Or, the bell ringer could sound it repetitively and loudly as a community warning system (i.e. to call people into town to fight a fire).

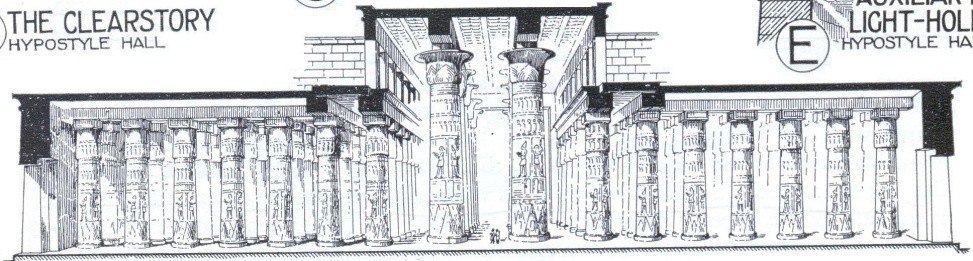

- On the plan it is evident that three doors led from the narthex into the nave [image 8.92]. The significance of “three” may have been an anti-Arian statement, or they could have been simply in the tradition of centuries of architectural history [images 8.93 and 8.94].

- Columns divide the interior into a nave and two aisles.

- Clerestory windows flood the basilica with light.

- The sanctuary includes a triumphal arch and the apsidal area of the conch.

- Surprise! There is no transept.

Two rows of 12 marble columns imported from the Sea of Marmara (literally, Sea of Marble) march the participant steadily forward toward the apse [image 8.95]. Stairs and the triumphal arch set the apse area apart and draw attention to the holy space even when no services are being celebrated. Only the mosaic apse and triumphal arch remain from the original decorating program; the side walls are thought to have also been decorated with Proconnesian marble (from the Sea of Marmara). The altar in which the saint’s relics are, or are not installed, is in the center front of this picture.

The Basilica of Sant’ Apollinare in Classe is a perfect example of a funerary basilica built over or adjacent to the tomb of an esteemed saint or martyr. The basilica is dedicated to the first bishop of Ravenna, Sant’ Apollinare, but his story is far from uncomplicated. According to tradition he was sent by St. Peter as a missionary to Ravenna where he worked for nearly 20 years before being lapidated (stoned to death) by pagans or teenage hoodlums, ca. 75 CE. In an alternative version of his story, having the audacity to convert people and perform miracles, he was brought before a Roman judge, tortured and martyred about 180 CE.10

Adding to the complexities of Apollinare’s story, this basilica was begun between 533 and 536. Those dates make it “newer” than the “New” basilica of Sant’ Apollinare Nuovo in Ravenna, which was begun during the reign of King Theodoric (r. 493-526). The appellation Nuovo was applied at the rededication when the saint’s relics were transferred from the Classe location during the Amorian dynasty (820-867). This is turning into an overly complex byzantine story (no pun intended!).

The basilica in Classe was consecrated by Bishop Maximianus on May 9, 549, just a little later than the more famous Basilica of San Vitale in Ravenna.11 As with the latter church, construction of the Sant’ Apollinare was made possible by generous subsidies from Julianus Argentarius, the mysterious banker who played a large role in religious life in Ravenna in the first half of the sixth century.

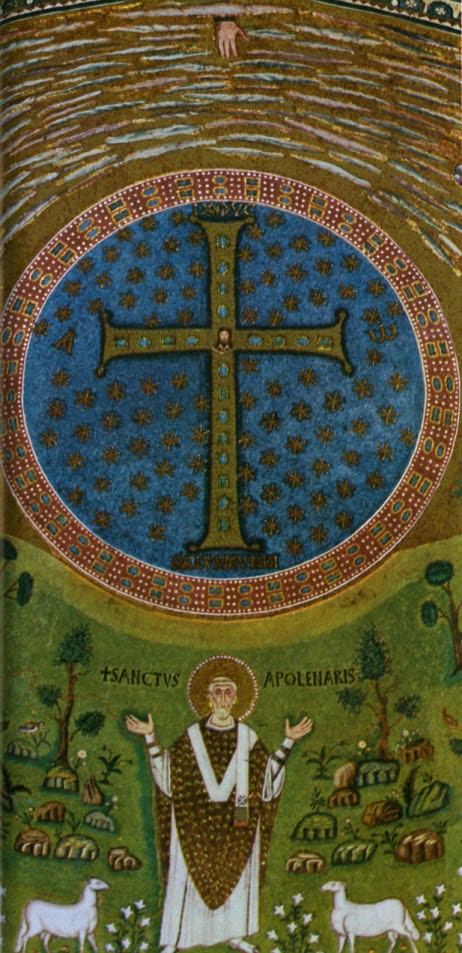

It is the apse at Sant’ Apollinare in Classe that is so overwhelmingly amazing. As we study the original sanctuary mosaic, at least nine scenes may be identified [image 8.96].

Scene 1. Where is Christ in this apse? Many observers misidentify the central figure [images 8.96 and 8.97] in the lower part of the mosaic as Christ. He is, after all, the largest figure. He has a halo, and is placed in a “divine” frontal stance. Sorry, but not a good guess. This figure is clearly labeled as “SANCTVS APOLENARIS.” Apollinare is dressed in a chasuble with a bishop’s pallium. His hands are extended in the orant position of prayer.13

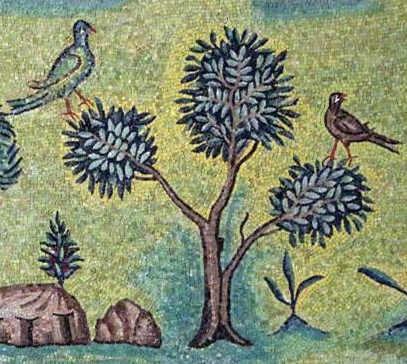

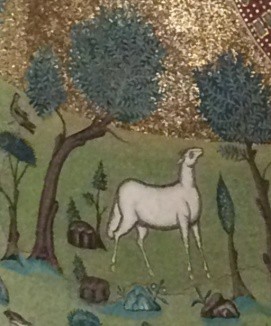

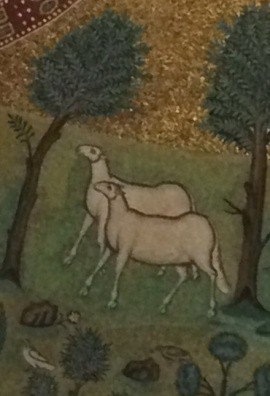

Scene 2. Saint Apollinare is standing in a beautiful green landscape with rocks, trees and birds. Twelve sheep walk toward him in orderly lines, six from the left and six from the right. These may represent the twelve apostles. It has been noticed that the first lamb on the saint’s right side is pure white; perhaps it represents Apollinare himself, who was believed, because of his ability to perform miracles, to have been a saint during his lifetime. The other five lambs appear dirty; these could represent catechumens (before baptism). Cleaned neophytes (baptized people) are on the saint’s left side.

As with all mosaics in Ravenna, those in the Sant’ Apollinare in Classe have been restored on many occasions. Red lines were added in the 1970s restoration to indicate which parts of the mosaic are still original.

Scene 3. While we’re near the saint, let’s study the landscape [images 8.98 and 8.99]. None of the rocks, trees or birds has the illusionary quality of Greco-Roman art. The details of nature are unimportant. In the flattened presentation of this abstract art people, animals and objects have value not for what they are, but for what they symbolize.

Scene 4. Perhaps Christ is one of the figures on the back wall of the apse? These are also prominent, and each seems to be standing in a niche which has been ornamented with curtains [image 8.96]. Sorry, none of these is Christ. In the first place they are not solitary; the focus is not on one, solo, divine image. These are four early bishops of Ravenna.

Ecclesius, bishop of Ravenna from 522 to 532, is on the left. We have seen him earlier in the apse mosaic of the San Vitale.17 The second is Severus, who was bishop of Ravenna in the 340s and whose cult was gaining momentum at the time of Sant’ Apollinare’s completion. The third is Ursus, who was bishop of Ravenna ca. 405-431 and who was responsible for the construction of Ravenna’s cathedral (Basilica Ursiana) and the adjacent Orthodox Baptistery.18 The fourth bishop is Ursicinus, who was bishop of Ravenna between 533 and 536 and who commissioned the initial basilica of Sant’ Apollinare in Classe. We’ve proven that these are historical, important people, but none is the focal point.

Scene 5. Look up, to the triumphal arch that surrounds the apse [image 8.96 and 8.105]. The sanctuary area is filled with abstract symbols. It must be remembered: symbols are the language of religion just as numbers are the language of science. Joseph Campbell’s admonition is relevant here: “Those who do not know that symbols hold hidden meaning are like diners going into a restaurant and eating the menu rather than the meal it describes.”19

The symbols across the lintel of the triumphal arch which forms the façade of the sanctuary are mostly unfamiliar to the modern reader. We remarked on them earlier in the dome of the Mausoleum of Galla Placidia20, and they are not difficult for us to identify. Based upon writings from the books of Ezekiel and Revelation and St. Jerome’s fourth century writings, the four writers of New Testament Gospel books are remembered by means of these symbols.

The book of John is very mystical, so the symbol for the writer is the eagle who sees this world from lofty heights [image 8.100]. In a similar manner to eagles soaring toward the sun, John’s commentary was seen as radiating the light of divine knowledge.

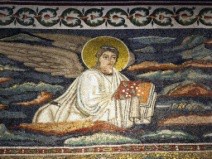

The symbol of a man is used as a mnemonic for the book of Matthew which traces Jesus’ genealogy to demonstrate his human nature [image 8.101].

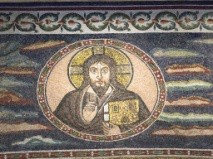

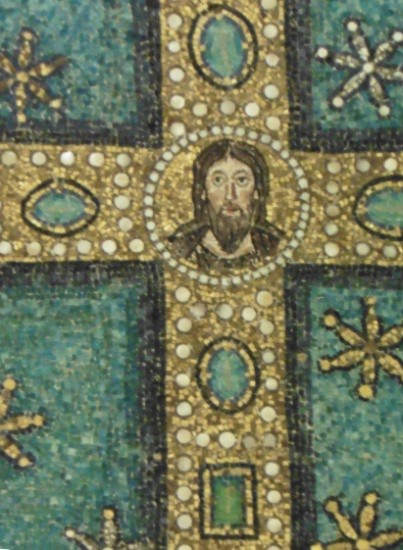

Aha! We have found one depiction of Christ. He is shown in the center as Christ the Pantocrator, the omnipotent world ruler. He is both mature and divine, with both a beard and a halo [image 8.102]. He is giving a benediction (blessing) to his followers. (Don’t you sense that there must be two more representations of Christ somewhere nearby?)

The memory device for the book of Mark is a lion because the text promotes the royal dignity of Jesus [image 8.103].

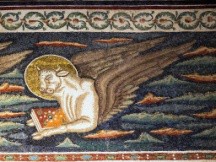

The book of Luke describes Jesus’ birth in a stable, so an ox is an appropriate prompt [image 8.104].

Scene 6. Twelve more sheep may be seen under the horizontal lintel [image 8.105]. Like the twin towers on either side of the narthex, these could be symbolic of faithful worshippers as they proceed in measured steps from the walled cities of Jerusalem and Bethlehem.

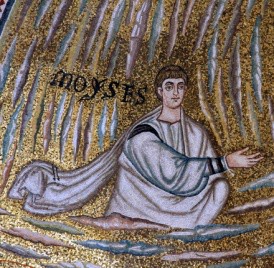

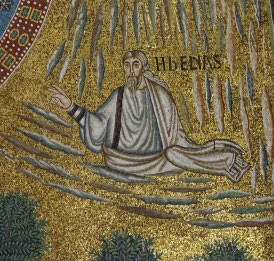

Scene 7. The arch itself [image 8.96] has been cleverly utilized as Mount Tabor for a depiction of the event known as “The Transfiguration.” At this time, as described in the three Synoptic Gospels (Mark, Matthew and Luke), Jesus revealed his divine nature to Peter, James and John. The story emphasized a crucial Anti-Arian theological point by affirming the duality of Christ, who was not only man and God at the same time, but was perceived by men as such at this event. The two large figures floating in the clouds are the prophets Moses and Elijah (labeled “MOYSES” and “HbELYAS”) and the three sheep to the left and right of the cross are symbolic of Peter, James and John.

The account from the book of Luke 9:28-36 is perplexing to us, and the event was probably also mystifying to the three disciples. “And it came to pass about eight days after these sayings, he took Peter and John and James, and went up into a mountain to pray. And as he prayed, the fashion of his countenance was altered, and his raiment was white and glistering. And, behold, there talked with him two men, which were Moses and Elias: who appeared in glory, and spake of his decease which he should accomplish at Jerusalem. But Peter and they that were with him were heavy with sleep: and when they were awake, they saw his glory, and the two men that stood with him. And it came to pass, as they departed from him, Peter said unto Jesus, Master, it is good for us to be here: and let us make three tabernacles; one for thee, and one for Moses, and one for Elias: not knowing what he said. While he thus spake, there came a cloud, and overshadowed them: and they feared as they entered into the cloud. And there came a voice out of the cloud, saying, ‘This is my beloved Son: hear him.’ And when the voice was past, Jesus was found alone. And they kept it close, and told no man in those days any of those things which they had seen” (KJV).29

Scene 8. It only makes sense that Christ would make a second appearance in this scene of the Transfiguration, and he does. The Divine Presence is expressed as the Hand of God. It is between Moses and Elijah and above the cross. In one’s imagination a voice from the cloud may be heard, saying, “This is my beloved Son: hear him.”

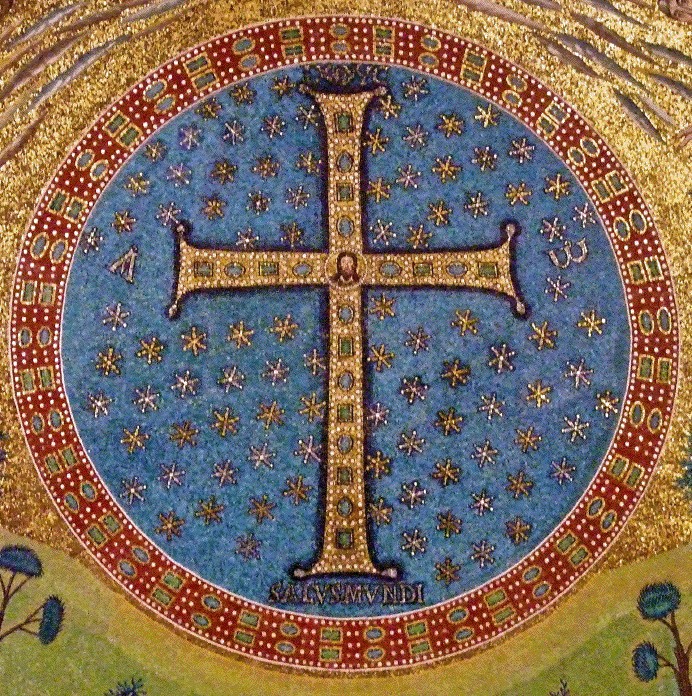

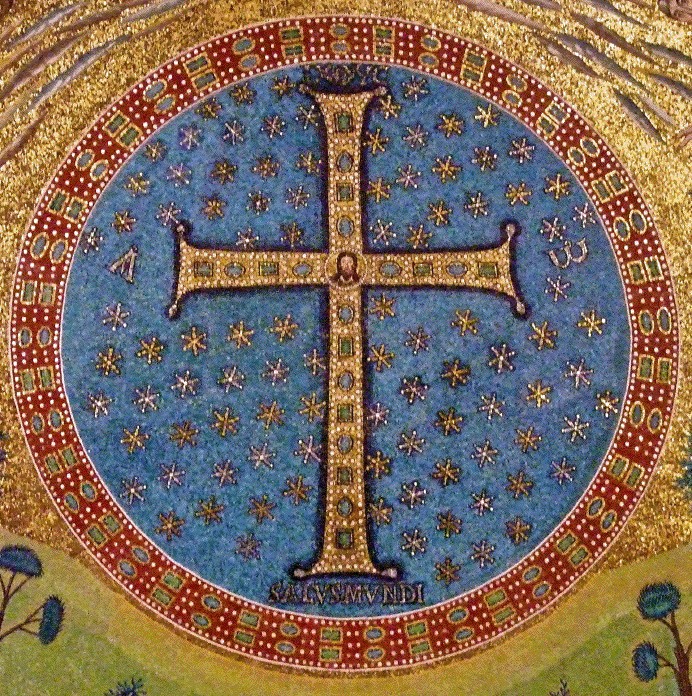

Scene 9. The third appearance of Christ is in a large jeweled cross set against a blue background. The cross suggests not only his crucifixion, but his victory over death and the Second Coming, an event that will be as mind-boggling as was the Transfiguration. The surrounding 99 stars in the star-spangled heaven are symbolic of the story of the “Ninety- and nine lost sheep” (Luke 15: 4-7).

Around the cross are additional statements about the significance of Christ. On the left and right arms of the cross are the letters Α (alpha, the first letter of the Greek alphabet) and Ω (omega, the last letter of the Greek alphabet), suggesting that Christ is the beginning and end of all time, and the Lord of All that is really important. Above the cross, we see the Greek word ΙΧΘΥΣ, which translates as “fish”, but it is also the acronym for “Ίησοῦς Χριστός, Θεοῦ Υἱός, Σωτήρ”, or “Jesus Christ, Son of God, the Savior,” a familiar phrase for early Christians. Below the cross are, in Latin, the words “SALVS MVNDI” (“Salvation of the World”).

We have identified nine stories presented in the masterpiece of the apse and triumphal arch at Sant’ Apollinare in Classe. As you have observed, a Trinitarian emphasis is still giving “correction” to the heretics. To accentuate the need to repair unorthodox thought, just one more example will be given. On the piers (vertical supports) of the triumphal arch are two archangels, Michael and Gabriel. They are thought to have been part of the original sixth century mosaics. They are dressed in imperial tunics and are wearing privileged red shoes. Each is holding a banner which reads “agios, agios, agios,” which is Greek for “holy, holy, holy.” The declaration was no doubt a reference to the Holy Trinity and an anti-Arian statement

In Byzantine art we are transported to an ideal alternative world to witness a mystical understanding of beauty. The abstract patterns and symbols suggest a world of the spirit. Unlike the pagan (i.e. Greek) past, the earthly beauty of a human body is no longer the exemplar of supreme beauty. And, contrary to today, neither is nature the exemplar of perfect beauty. These Christians were members neither of the Zeus Affiliates nor of the Sierra Club.

Under the influence of Augustinian (and ultimately Platonic) thought, the heavenly city of God was so far removed from this earthly city that humans could only catch glimpses. God was understood to be so spiritual, so unitary that humans could not know him directly. As you have witnessed here, God was so removed from the things of this world that we could barely find him. And if you didn’t know to look for God in the center of the cross, you would never find God.

But we want to glimpse that world! So we devise lamps that will lift us to that mystical realm: tall, elongated candlesticks on which we can place even taller tapering candles. “That’s the best we can do for today, but perhaps tomorrow’s engineers with theatrical lights can do better.” And, they do!

You have before you two images of the medallion in the apse at Sant’ Apollinare in Classe. The first was taken on a sunny day, under natural lighting. The second was taken at night when the stage was set for a performance by the Westminster Boys’ Choir.

References:

1. Public domain at upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/3/3c/Statua_di_Augusto-_di_fronte_Sant %27 Apollinare _in_Classe.jpg

2. See Hartman, Kathleen J. “Chapter 8, Witnesses for Idealism: Sant’ Apollinare Nuovo.” Humanities: New Meaning from the Ancient World. Colorado Springs, CO: Pikes Peak Community College, 2020. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

3. See Hartman, Kathleen J. “Chapter 7, Constantine’s Great Decisions.” Humanities: New Meaning from the Ancient World. Colorado Springs, CO: Pikes Peak Community College, 2020. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

4. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Sant%27Apollinare_in_Classe_(Ravenna)_-_Exterior# /media /File:Ravenna- 252-San_Apollinare_in_Classe-1985-gje.jpg

5. European Commission website at http://www.heritage-route.eu/en/ravenna/gallery/#.X71LI81Kj4Y

6. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category: Plans_of_Sant%27Apollinare_in_Classe_ (Ravenna)#/ media/ File:Ravenna,_San’Apollinare_in_Clas se,_alaprajz.gif

7. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Great_Temple_of_Ammon_-_Karnak_40.jpg

8. Public domain at www.khanacademy.org/humanities/ap-art-history/ancient-mediterranean-ap/ap-ancient-etruria/a/temple-of- minerva-and-the-sculpture-of-apollo-veii

9. Public domain at ccsearch.creativecommons.org/photos/b627f888-2b23-4042-a328-a0febd08dd9a

10. Peter Chrysologus, Bishop of Ravenna 433-450, declared that Apollinaris did not die of wounds inflicted on him, so he was not a martyr. Verifying that idea, the depiction of him in the apse at Sant’ Apollinare in Classe does not show him with a martyr’s crown. Research conducted in 1954 suggested that only some of the relics were taken to Ravenna and the remainder were still buried in Classe, beneath the present basilica. Was the whole story a prank?

11. See Hartman, Kathleen J. “Chapter 8, Justinian, Master of Three Powers: San Vitale.” Humanities: New Meaning from the Ancient World. Colorado Springs, CO: Pikes Peak Community College, 2020. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

12. Public domain at upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/a/a6/Stappoclasseaps.jpg

13. See Hartman, Kathleen J. “Chapter 7, Anticipating Byzantine Culture.” Humanities: New Meaning from the Ancient World. Colorado Springs, CO: Pikes Peak Community College, 2020. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

14. Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris, “Sant’ Apollinare in Classe, Ravenna (Italy),” in Smarthistory, December 10, 2015, accessed October 30, 2019, smarthistory.org/santapollinare-in-classe-ravenna-italy/

15. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File: Meister_des_Mausoleums_der_ Galla_Placidia_ in_ Ravenna_ 002.jpg

16. Public domain at upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/0/02/Sant%27apollinare_in_classe%2C_mosaici_del_catino%2C_trasfigurazione_simbolica%2 C_VI_secolo%2C_10_giardino_%28con_restauri%29_2.jpg

17. See image 8.71 in Hartman, Kathleen J. “Chapter 8, Justinian, Master of Three Powers: San Vitale.” Humanities: New Meaning from the Ancient World. Colorado Springs, CO: Pikes Peak Community College, 2020. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

18. See Hartman, Kathleen J. “Chapter 8, Orthodoxy vs. Heresy: Orthodox and Arian Baptisteries in Ravenna.” Humanities: New Meaning from the Ancient World. Colorado Springs, CO: Pikes Peak Community College, 2020. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

19. Joseph Campbell, The Power of Myth, 1988.

20. See Hartman, Kathleen J. “Chapter 8, Development of Symbolic Art: Galla Placidia.” Humanities: New Meaning from the Ancient World. Colorado Springs, CO: Pikes Peak Community College, 2020. CC BY-NC 4.0 License.

21. Ibid.

22. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Sant%27Apollinare_in_Classe#/media/File:Sanapolinclasse02.jpg

23. Ibid.

24. Ibid.

25. Ibid.

26. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Upper_register_-_Triumphal_arch_-_Sant%27 Apollinare_ in_ Classe_-_Ravenna_2016.jpg

27. Public domain at commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Moses_-_Sant%27Apollinare_in_Classe_-_Ravenna_2016.jpg

28. Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris, “Sant’Apollinare in Classe, Ravenna (Italy).

29. The Transfiguration was a well-known theme in religious art. Another outstanding sixth-century mosaic depiction of the Transfiguration is at the Monastery of Saint Catherine at the foot of Mount Sinai (Egypt). Renaissance artist Raphael’s final painting, which has become a famous depiction of the Transfiguration, is now at the Vatican Museum.

30. Photo by the author, Kathleen J. Hartman, 2016.

31. Ibid.

32. Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris, “Sant’Apollinare in Classe, Ravenna (Italy).

33. Photo by the author, Kathleen J. Hartman, 2016.

34. Ibid.

35. Ibid.

36. Public domain at upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/3/3a/Archangel_Michael_-_Triumphal_arch_-_Sant %27Apollinare_in_Classe_-_Ravenna_2016.jpg

37. Public domain at upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/f/fb/ Sant%27apollinare_in_classe %2C_mosaici _dell %27arcone%2C_arcangelo_gabriele%2C_ VI_secolo.jpg

38. Photo by the author, Kathleen J. Hartman, 2016.

39. Ibid.

40. Ibid.