7. The Four Functions and Their Archetypes

The fundamentals of our approach to studying mythology are based upon Joseph Campbell’s writings, as well as upon statements made in conversation with Bill Moyers in The Power of Myth video series, first broadcast in 1988. Understanding of the heroic principle is also based in part upon the work of Christopher Vogler in The Writer’s Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers, 3rd Edition.1

Campbell references four main functions of mythology as a cultural/societal phenomenon:

- The Mystical Function: “Opening the world to the dimension of mystery … [realizing] the mystery that underlies all forms.”2

- The Cosmological Function: “Seeing [the totality of experience] as manifest through all things … the universe becomes (as it were) a holy picture, [so that] you are always addressed to the transcendent mystery”.3

- The Sociological Function: ”… validating or maintaining a certain society; ethical laws, the laws of life in the society … the values of [a] particular society.”4

- The Pedagogical Function: “How to live a human lifetime under any circumstances.”5

We can view these functions as progressing from the general and abstract (The Mystical Function) to the specific and concrete (The Pedagogical Function). Thus, we can approach all of them through the lens of how they assist the individual toward self-actualization via the path of understanding the relationships of self-to-self (Pedagogical Function); self-to-society (Sociological Function); self-to-universe (Cosmological Function); and self-to-spirit (Mystical Function).

Through the mechanism of exploring one’s own inner relationship with the various levels of human experience in the context of the fundamental fabric of existence, the value of mythology is emphasized by focusing one’s awareness toward the interconnectedness of all life’s experiences.

It is also useful to associate these four primary functions of mythology with specific archetypes that “embody” the essence of the functions.

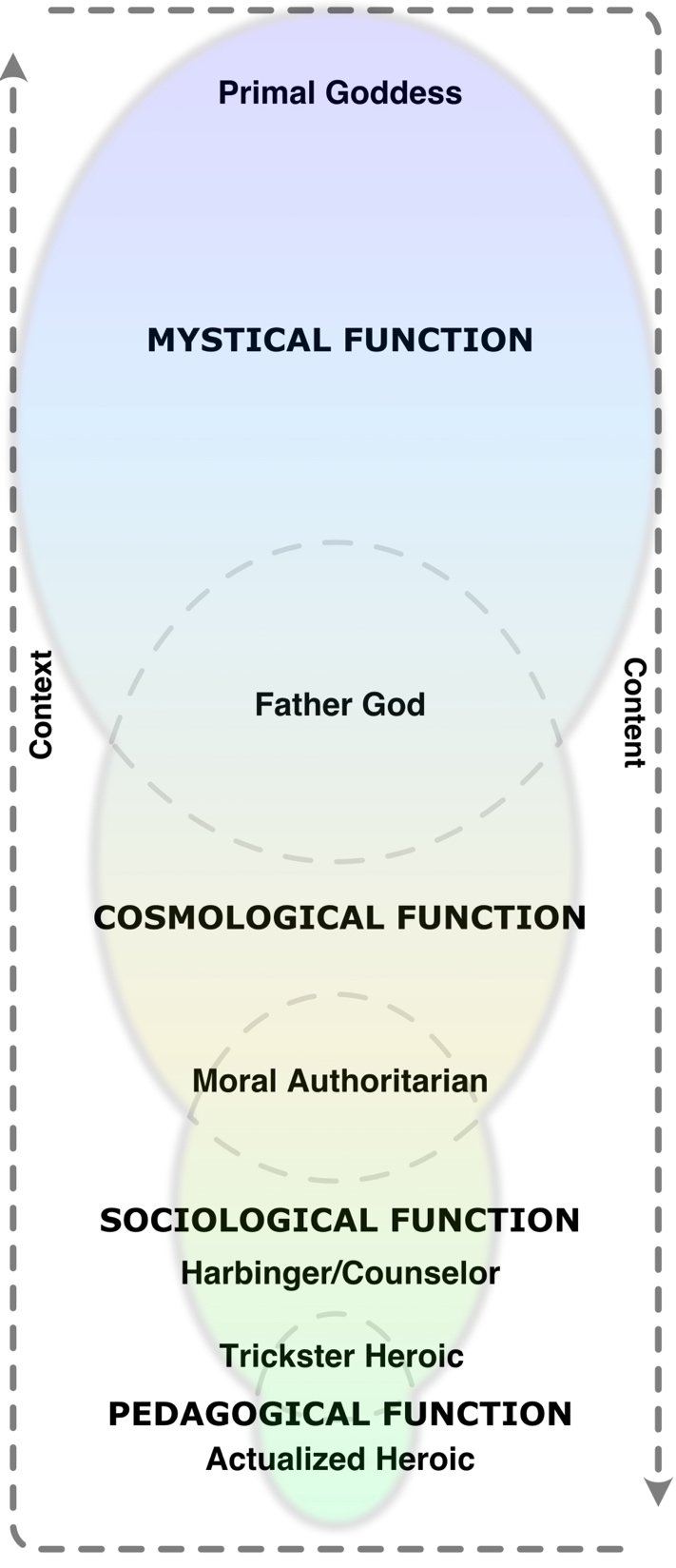

Reading the Mythic Structure Diagram

As the geometry and coloration of the Mythic Structure Diagram see figure 7.1 implies, there is seldom a hard-and-fast dividing line between one function and the next. They flow into one another, as befits a mythos environment. While there is a “progression” from the abstract to the specific, this is not to be understood as a well-defined path.

The arrow across the top and down the right-hand side indicates that as we read down the diagram, the content of the functions changes and becomes more specific. In the Mystical Function, the content is literally all of existence; in the Cosmological Function, the content is limited to that of the physical, material universe; in the Sociological Function the content is further restricted to that of a given culture/society; and, finally, in the Pedagogical Function, the content is focused on the individual experience of life.

The arrow across the bottom and up the left-hand side indicates that even as the content narrows, the context broadens. Explorations within the Sociological Function, for instance, must be undertaken in the broader context of the Cosmological and Mystical Functions. A culture/society exists within the natural world, which is “contained” within all of reality, itself.

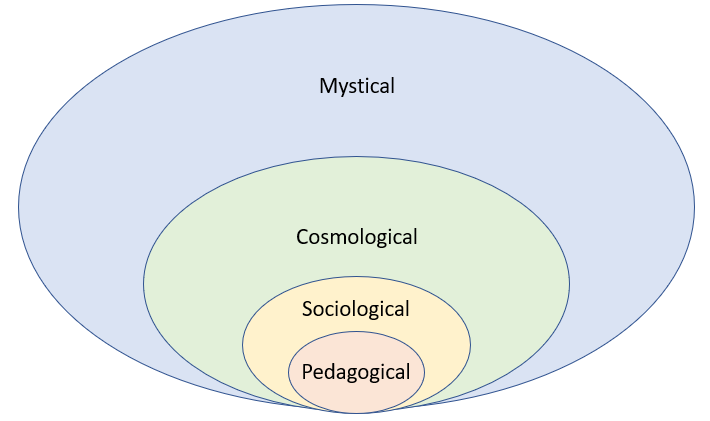

Context-centric Mythic Structure Diagram

In terms of the contextual relationships, an alternate representation might be:

… which encodes that the context of the Pedagogical Function is completely contained within the context of the Sociological Function see figure 7.2, which is completely contextualized within the Cosmological Function, which is embedded within the Mystical Function.

The downside of a representation like this is that it implies a rigid hierarchy between the functions which does not exist. The Pedagogical Function is contextualized within the Sociological Function, but it is in no way subordinate to it.

In the former diagram (figure 7.1), the Primal Goddess is listed at the very top of the diagram because in her primordial state she is simply an amorphous expression of the “… mystery that underlies all forms … that informs all things … [and] is beyond all categories of thought.”6 In this form (figure 7.2), she is less a personification than a conceptualization. As one progresses through the Mystical Function toward the Cosmological Function, she becomes more personified as specific goddesses within the various mythologies which sprang up with human societies.

In the transition zone between the Mystical Function and the Cosmological Function lies the Father God. With the transition from simply experiencing existence to assessing the process of living, human consciousness became more rigorously systematized, relying more and more on logic and rationality to construct its worldview. Thus, the Father God usurps the creator role from the Mother Goddess; she is seen to have created randomly and erratically, whereas the creative energies of the Father God are directed to specific goals and purposes.

In the transition zone between the Cosmological Function and the Sociological Function is the Father God in his guise as Moral Authoritarian. Since his creative efforts in the physical universe are purposeful and directed, the physical universe functions according to set rules and limits which are knowable but non-negotiable. The notion that the Moral Authoritarian has specified how the universe shall work and decreed that it never vary from his plan, this stricture becomes imposed on human society, as well, when the male energy becomes the dominant organizing principle.

In the midst of the Sociological Function we find the dualistic Trickster roles of Harbinger/Counselor. As the Harbinger, the Trickster reminds individuals that society has decreed rules of behavior, the transgression of which will result in punishment. As the Counselor, the Trickster contrastingly reminds the individual that blindly following a rule that may have been valid and efficacious at one time but has since become outmoded or counter-productive is nothing less than slavery. The Counselor is the red-flag waver, signaling society that its view is becoming too narrow and confined and danger lies ahead.

In the transition zone between the Sociological and Pedagogical functions, then, we find the Trickster Heroic; the Counselor who moves beyond merely raising an alarm and decides to take action to address the Problem or Challenge it has identified.

Finally at the bottom of the diagram is the Actualized Heroic; that aspect of the Heroic archetype which is available to anyone (or anything) that is willing to put itself on the line for the sake of others or in service of a morality greater than itself, is Heroic. By “actualized” here is meant that the True Heroic is not limited by gender, race, ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation, age, species, or even to organic life. A cybernetic character which is capable of ethics, morality, compassion, and empathy and is also willing to endanger its own existence for its principles, is Heroic.

As such, the Actualized Heroic is accessible to all and can form a foundation for the life path of anyone. Bill Moyers said to Joseph Campbell:

Well, the interesting thing to me is that far from undermining my faith, your work in mythology has liberated my faith from the cultural prisons to which it had been sentenced.7

To which Campbell replied, “It liberated my own. I know it’s going to do it with everybody who really gets the message.”8

In addition, “actualized” reflects that a Heroic at this level is enlightened to “live a human lifetime under any circumstances.”9

Imposing Logos on Mythos

It cannot be denied that the enumeration of the Four Functions and the associated Archetypes is an effort to impose logos on mythos, but for the purposes of collective study and contemplation of mythology across time, some common language must be developed. A lone consciousness wrestling with the symbols and metaphors of mythology may be capable of epiphany about the human condition and experience, but how does it then communicate its realizations if it has no words to express them?

The challenge, then, becomes adopting a logo-centric method of organizing our thinking about mythos and its meanings, without becoming locked into a structure of discussion and description which curtails the free-ranging liberty that true exploration depends on.

It seems that the best approach is to simply remain aware that all language is open to interpretation, and that all verbal and/or literary expression is, perforce, approximate. The principles that guide conflict resolution become useful, here. Statements like, “What I think I hear you saying is….” must take the fore, and structuring information exchanges around this model of sentence construction inevitably promotes thinking structures of like form.

It is also sometimes of vital necessity to “rise above” the affective domain of mythos and take a more objective, “big picture” approach, especially when the actions of characters in myths are distasteful, discomfiting, or downright disgusting to our modern sensibilities. Lowell Bennion, in his 1959 book, Religion and the Pursuit of Truth, wrote:

It must be possible to try to understand the actions and worldview of earlier cultures without falling into judgement or recrimination.11 As regards contemporary societies, there is certainly the danger of falling into the social relativistic apathy of “It’s their way; I have no right to interfere.” However, for past societies (even previous versions of our own), there is no undoing what was done, and the danger becomes one of denial: “I can’t do anything about it, so I just won’t think about it,” or (worse) revisionism: “That’s not what happened, at all.”

Being aware of past inequities and injustices need not be a matter of assigning blame or attributing guilt, but a past ignored is more easily repeated. The study of mythology, with all its warts fully visible, enables us to recognize that we have the wisdom of past experience upon which to draw, and thereby make better choices today for a better future tomorrow.

The Archetypes Of The Functions

A dictionary defines “archetype” as:

- The original pattern or model from which all things of the same kind are copied or on which they are based; a model or first form; prototype.

- (In Jungian psychology), a collectively inherited unconscious idea, pattern of thought, image, etc., universally present in individual psyches. [emphasis added]

When Campbell uses the term “archetype”, he means both of these (much of Campbell’s work was an adaptation of Jung’s prior efforts). Both Jung and Campbell recognized a potentially infinite register of archetypes; here, we are primarily concerned with four:

- The Primal Goddess

- The Father God (as Usurping Creator and as Moral Authoritarian)

- The Trickster (as Harbinger/Counselor and as Trickster Heroic)

- The Heroic

(The archetype of the Victim/Damsel makes an appearance as well, in connection with the disempowered and demoted Goddess, and the archetype of the Villain is also referenced, as one of the expressions of the Trickster.)

Each of the Four Functions, then, is in some sense “expressed through”, “embodied in”, or “personified by” an archetype (the Father God and the Trickster are each associated with aspects of two functions via two of their incarnations, (details below).

Note that while the various mythical functions are associated with particular archetypes, it seldom happens that a given myth is solely focused on a single function or a single archetype. Although any given myth may have as its primary focus one of the functions, for instance, a creation myth may be couched in the terms of the Mystical or Cosmological Function, there will likely be at least tangential references to the other functions, as well.

The Sumerian Atrahasis flood myth, for instance, reflects the Mystical function in that the Upper and Lower gods all pre-exist without explanation, as does the Earth into which the Lower gods are digging channels. The Cosmological Function is referenced when the myth describes that the channels are the lifelines of the land and specifically mentions the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. The Sociological Function is present through the depiction of the society of the gods being stratified and hierarchical (there are Upper gods and Lower gods), and in the depiction of the creation of humans as mortal laborers forged (literally) to relieve the Lower gods of their onerous duties. The Pedagogical Function permeates the myth from the standpoint of various characters identifying Challenges or injustices and taking action to address them. So, while the Atrahasis myth might be superficially classed as a “creation myth”, it serves far more (and more subtle) purposes.

The Limits of Labels

Note that this approach uses “heroic” rather than “hero”, because the latter is gender-specific to the binary male in English. Also, “hero” can be used/interpreted as a limiting label when applied to a person. To label someone “a hero” is often accepted by the person, themselves, as well as the wider community, as a sort of level of expectation for all future behavior. It sets the bar at a level which is simply not attainable 100% of the time.

Thus, acts should be described as “heroic”, and the person who performed the act should most certainly be recognized and praised for having exceeded the “norm” and accomplished something extraordinary. But to call the person “a hero” is to saddle them with the expectation of exceptional behavior in all instances at all times in the future, and that is not a reasonable expectation.12

To strip someone of “hero” status because they’re having a bad day and snipped at someone without thinking is rank injustice. It also perpetuates the social inequity of “you’re only as good as your most recent mistake.” A moment of human weakness today certainly does not “erase” a moment of heroic exceptionalism yesterday.

This is not to say that past heroism affords someone carte blanche against future transgressive behavior: A crime today is not justified by a sacrifice yesterday. But, context is all of history, personal and collective. Today’s behavior is always predicated on past stimuli. A heroic act should be acknowledged and rewarded, but a villainous one should never be excused.

This also helps avoid the problem of false confidence in dealing with difficulties. All challenges are unique, and no solution is absolute. Just because today’s challenge bears similarities to yesterday’s challenge does not mean that yesterday’s solution will perfectly address it.

Aspects of yesterday’s solution may be borrowed and adjusted to suit the new situation, with new aspects incorporated to address the uniqueness of today’s challenge. But to fall into the trap of thinking that a given solution will always be effective against every challenge purely on the basis of their superficial similarity to past challenges is nothing less than “putting off until tomorrow”. There is always a “pay me now price,” and a “pay me later price”, and the “pay me later price” is always higher.