9. The Cosmological Function And The King God

Examination and exploration of the natural world led to the inevitable conclusion that natural events happen as a result of knowable causes and effects, which engendered the idea that the universe functions according to certain knowable, immutable laws. A dropped object falls to the ground; water seeks its own level; decay is the default process of life;1 cause always precedes effect.

The reasoning seems to have been something like:

- There are universal laws of the natural world which are always true and unbreakable.

- Rules of behavior result from the ordering of thoughts by conscious will.

- Therefore, the universal laws of nature must have been formulated, enacted, and are continually enforced, by an overarching, controlling consciousness.

Protology: Architectural Myths of Origin

The Cosmological Function is thus associated with architectural creation/origin myths, in which the physical universe is conceived, manifested, structured, and ordered by the conscious agency of a deity or deities. The manifested deity or deities (who often arise increatus) set about to build the universe according to some design.

Thus, all automatic origin myths become architectural at some point. This may happen quickly, as we see in the first line of Genesis, “In the beginning, God created the Heavens and the Earth.”2 The first phrase, “In the beginning, God,” is an automatic origin myth; neither God’s origin nor nature is explained — it is assumed, he is increatus. The remainder of the passage, “created the Heavens and the Earth,” begins an architectural origin myth; the physical universe and everything in it brought into existence through the conscious actions of God, for his own reasons and purposes.

The overarching, controlling consciousness of architectural myths of origin was almost everywhere assigned to a male deity in preference to a female. Edith Hall, Professor in the Department of Classics and Centre for Hellenic Studies at King’s College, London, tells Bettany Hughes:

Walled cities start to be built all around the … Mediterranean world, and you get large armies; you get very powerful kings; you get accumulation of money and capital. You get something you’ve got to defend, something really worth fighting for. And violence, in terms of policing the world, becomes — I think — much more common. Mass violence, between different communities. And that’s the moment at which you start to get these big, masculine gods, that’s I think a reflection of a much more militaristic culture on the ground.3

Harvey Whitehouse, et. al., confirm this, in an article titled “Big Gods came after civilization, not before”:

But why would a male god be so much better suited to this task than a goddess?

Shlain suggests that it was because big-game hunting generally fell to males:

Thus, according to Shlain, the average male became more goal-oriented and task-focused, while the average female became more process-oriented and multi-tasking. He also contends that the perpetuation of culture became the purview of mothers, while socializing the young became the task of fathers.6

Society, by its very nature, is a set of permissions and prohibitions dictated to individuals by the collective will of the body politic. Thus, the argument goes:

- The laws of nature are formulated, enacted, and continually enforced, by a Father God.

- Society is bounded by laws, just as nature is bounded by laws.

- Because males are more logically minded than females8, it is in the male nature to explore and apprehend natural laws.

- Familiarity with the essence and functioning of natural law qualifies males to conceive, enact, and enforce societal laws.

(Yes, there is more than a hint of a circular argument here, but, as Gary Zukav points out, mythos “… follows a much more permissive set of rules”9 than does logos.)

The fifth and final point is the least palatable. Because, as Shain says, “Hunting demands ‘cold-bloodedness’ tinged with cruelty; nurturance requires emotional generosity combined with warmth,”10 and hunters are perforce male11; males became, therefore, naturally better equipped to enforce the sometimes rigorously inequitable and unjust rules of society in order to ensure the greatest good to the greatest number for the majority of the time.12

This has also been supposed to explain that…

The male brain tends to be more efficient to lateralize and compartmentalize, which has the advantage of making him more task-focused. The female brain has more [nerve] connections and constantly cross-signals and takes in more, so it tends to see and feel more than the male brain.13

An example: It so often happens that when a hetero-husband is discovered to have cheated on his spouse, his response is something like, “It was one time; it has nothing to do with us!” He apparently literally believes that his dalliance with another woman is completely and utterly unrelated to his relationship with his wife.

The spouse, on the other hand, tends to respond along the lines of “It has everything to do with us!” In her awareness, he is her husband at all times and in all situations14, whether she is physically present with him or not; as far as she is concerned, he might just has well have engaged in sex with the other woman while his wife was in the same room.

It is not that either of them is more-or-less “right” about the situation; they simply have conflicting understandings of the circumstances. Shlain concludes:

Evolution, in time, equipped men and women emotionally to respond differently to the same stimuli. This resulted in men and women having different perceptions of the world, survival strategies, styles of commitment, and, ultimately, different ways of knowing: the way of the hunter/killer and the way of the gatherer/nurturer.15

A Structured, Orderly World

The architectural aspect of protology (origin myths) appears in some of the earliest written accounts of mytho-religious literature. Most of these record the origin and nature of the structure and order of the physical universe; enumerate the specific actions of a seminal male deity16 who brought it all about; and emphasize that organizing physical principles and processes are crucial for a smoothly functioning reality that is both conducive and kindly to human existence.

Norse mythology reflects this model when Odin and his brothers construct the Nine Realms from the body of the Frost Giant, Ymir; and, of course, the Tanakh17 enumerates in great detail in the book of Genesis the order in which Yahweh creates the various physical aspects of the universe.

This was also captured in the European Medieval concept of the Great Chain of Being figure 9.1, a hierarchical structure of the physical universe, both animate and inanimate, progressing upward from minerals at the bottom to God at the pinnacle.

The underlying message is that the universe has the structure it does for good reasons, and if you’re going to try to manipulate it, you should do so intelligently, with a thorough understanding of the possible and potential effects your actions will produce.

This is the other face of the Divine Father: the Moral Authoritarian; the King God who has ordained the universe to be as it is, decreed that it is perfect as-built, and demands that his order be honored and his natural laws be observed and obeyed.18

In Egyptian Myth: A Very Short Introduction, Geraldine (Harris) Pinch, faculty of Oriental Studies at the University of Oxford, discusses the Memphite Theology, sourced to an ancient scroll which was partially duplicated on a stele known as the Shabaqo Stone.19 She relates that in this account, the creator deity, Ptah, is linked,

… with a whole series of deities who represent elements of the primeval world … [including] Ptah-Nun and Ptah-Naunet, the male and female aspects of the dark, watery chaos of the primeval ocean. The potential for intelligent life was inherent in this ocean, but was not realized until the spirit of the creator attained awareness.20

Note here the echoes of animistic thought; the quintessential material from which physical reality will arise or be constructed is described as a mysterious “stuff” which has no nature of its own, but holds in suspension all possible things, awaiting a directing consciousness to bring them into being.

This is strikingly similar to Hindu cosmogony, as when Campbell quotes from the Upanishads, “In the beginning there was only the Great Self, reflected in the form of a person. Reflecting, it found nothing but itself, and its first word was, ‘This am I.’”.21

Geraldine Pinch tells of Atum of Heliopolis, who, as described in the Pyramid and Coffin Texts:

A more specific relationship to the Cosmological Function is found in the retelling of the story in the Memphite Theology, in which “… Ptah is said to bring deities, people, and animals into being by devising them in his heart and naming them with his tongue.”23

This power of divine speech is ubiquitous in architectural creation myths, and serves to illustrate the awareness of the earliest societies of the power of first spoken, and then written, language.24 Pinch emphasizes that “… the ‘divine words’ of Ptah can, like hieroglyphs, make thoughts real”25 [emphasis added].

If we posit that “thoughts” in this sense, refers to “cogitations born of contemplation and exploration”, then the concept is demonstrably logos-oriented, since experience and feeling are indelibly linked to mythos. Speech and written language are structured and ordered expressions of the results of asking questions and discovering answers, clearly a function of logos-knowledge.

Thus, a structured and orderly world, created by structured and orderly thoughts, realized by structured and orderly language, must be the product of the agency and actions of a male deity, himself functioning in a structured and orderly fashion.

Pinch observes that, “On one level, the Memphite Theology can be seen as a classic validatory myth. It justifies the continued existence of institutions such as kingship and the priesthood by giving them divine origins,”26 but she also points out that, “… local deities of both genders achieved the status of creator, [and] where a temple had two principle deities, both could be given creation myths,”27 and that, although “Egyptian cosmogonies usually list several, apparently contradictory primal events, [they] do not seem to have regarded their creation myths as literally true, [but] more like highly charged metaphors, drawn from the natural world.”28,29

This power of divine speech also appears in the Popol Vuh, the Mayan account of creation, wherein “Creation begun with a declaration of the first words,”30, and of course, in the first chapter of the Hebrew Bible, “And God said, Let there be light: and there was light,”31 as well as the first verse of the Christian New Testament Book of John: “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God … and the Word was made flesh….”32

Linear and Cyclical Time

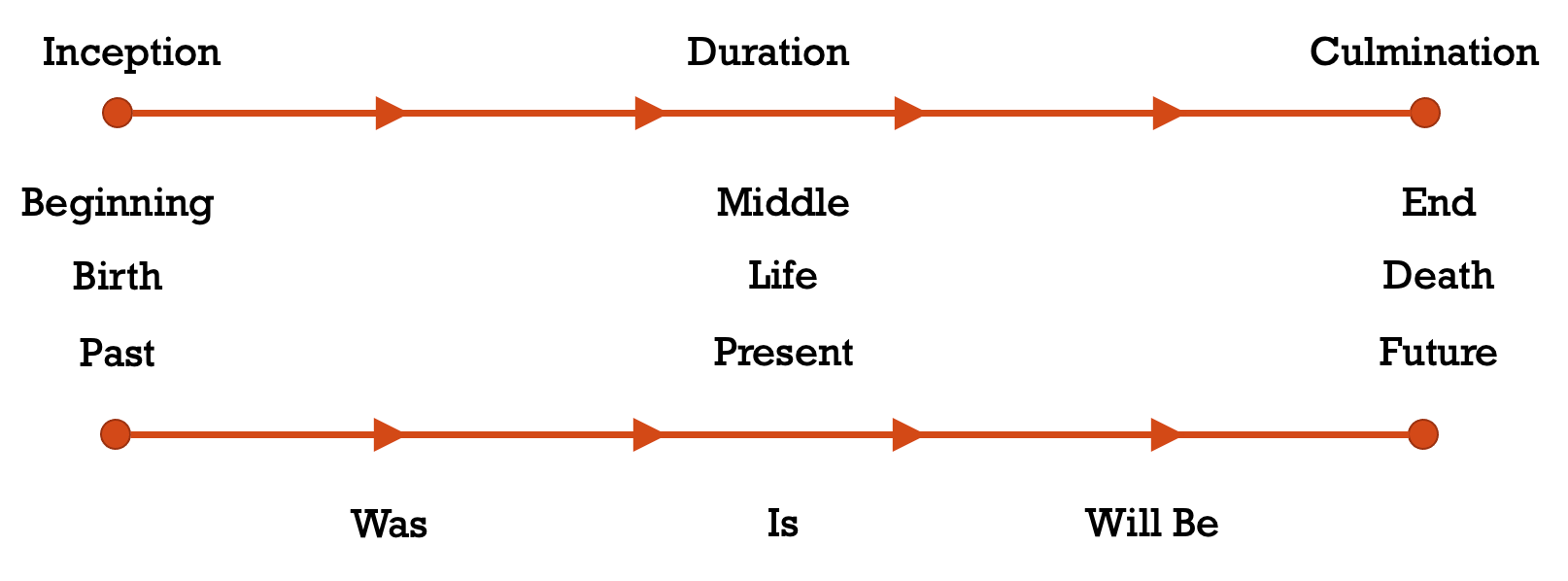

Most logos-structured worldviews see time as linear figure 9.2, following a path from a starting point to a conclusion, an ending which is inevitable, inescapable, and absolutely final.

In addition, most cultures which use an alphabet writing modality also depict the flow of time as left-to-right (or, more rarely, top-down), so that on a timeline, earlier dates are to the left of later ones. This is reflected in many mythologies which have an eschatological mode, both at an individual and a universal level. An eschatology33 is any system of stories concerning last or final matters, such as an apocalypse, a judgment, an afterlife, etc.

These mythologies purport to describe or predict for an individual what to expect after death (predicated upon a moral-ethical assessment of the conduct of their lifetime). However, they as well elucidate what form a general “end of the world” will take, and whatever (if anything) follows — which is usually expected to be utterly different and generally “better” than the current situation (at least for those who qualify to partake in it).

All of these systems tend to have strong architectural protological elements; a Creator brought the universe into being, is watching over it as it functions, and will either bring about or at least preside over its demise when its function comes to an end. It is easy to see how this worldview came about.

In everyday experience, everything has a beginning, an existence of some duration, and an ending. Plants sprout, grow and flourish, and finally wither; animals are born, live and interact, and eventually die. Even mountains — the very rocks, themselves — are not permanent, but rise, maintain for a time (a very long time, in human terms, but a finite time), and erode away. It makes sense that this becomes entrenched in a culture’s “understanding” of “how things work.”

Other worldviews, however, see time and existence as more-or-less cyclical (at least when it is functioning properly). The totality may be subdivided into lesser units which have a finite nature, but the essence of being — the nature of existence — is, itself, unbounded, having no beginning and no ending. It is transcendent.

Try imagining a canvas so large that an infinite number of paintings of any individual size may be created on it, but regardless how many paintings are painted on it, there is always room for one more, of any size. The mind literally rebels.

A more practical example can be seen in a standard analog clock figure 9.3. Each cycle of the minute hand around the clock denotes an hour of time, and each cycle of the hour hand defines a day. But the circle of the clock’s circumference, itself, has no beginning and no end. If an analog clock were able to function in perpetuity,34 the minute and hour hands would cycle around it endlessly, ceaselessly marking out individual minutes and hours, but never coming to an end of their journey.

Similarly, a wall-calendar with 12 sheets, each divided into regular arrangements of squares beginning with January 1 in the upper-left of the first page and concluding with December 31 at the lower-right of the last page tracks the passage of a year. But time, itself, does not come to a stop at the end of the last page; a new calendar with a similar structure replaces the previous one, and another year is counted through (again, theoretically in perpetuity).

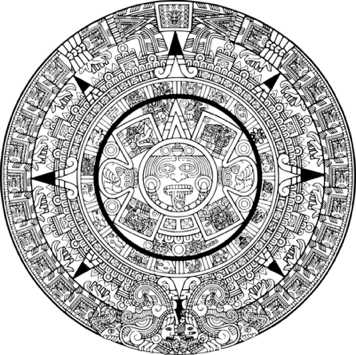

Misunderstanding of this principle is why so many people incorrectly believed that “time” would “end” when the Mayan Long-Count calendar see figure 9.4 “ran out” on December 21, 2012; the famous circular carving is simply a depiction of a very long period of time (5,125 years), but each of those periods is believed to be preceded by a previous 5,125-year period, and it is assumed that each will be succeeded by a following 5,125-year period, for as long as the universe exists.

The Ancient Egyptian view of time was primarily cyclical on a universal level35. Again, it is not hard to see why this would be so: each day the Sun rose in the east, travelled across the sky, and set in the west. Each daylight period was followed by a dark period in which the Moon36 and various arrangements of stars (constellations) were visible, also traversing the sky from east-to-west.

The nighttime period, however, had more variety than the daylight period; the shape of the Moon changed in a regular, predictable cycle, and which constellations were in the sky also shifted over time. Counting from one Full Moon to the next yielded a count of about 29 cycles of the Sun rising and setting. Counting from the night when a given constellation was directly overhead in the middle of the night, to the next time it was in that precise position again yielded about 365 risings of the Sun.37

So, even though the Sun was “born” each morning and “died” each night, and the Moon was renewed on a monthly basis, and the heavens cycled on a yearly scale, these cycles, themselves, never came to a stop — unless there was an eclipse, which universally terrified logos-thinking humans all over the world for thousands of years, until it was noted that these events, too, occurred on a regular, predictable cycle.

So, a plant may sprout, flourish, and wither, a person may be born, thrive for a time, and die, but time itself continued to flow. Thus, while Egyptian mythology does have an origin story (several, in fact; see above), and while it does have an eschatological mode for people, animals, and objects, it does not foresee and end for the universe, itself.

Hindu cosmogony takes a similar view, but accounts for much longer divisions of perpetuity. In this view, infinite time is divided into the Yuga38 Cycle a series of repeating cycles each of which is called a “maha yuga”39 (or sometimes a “chatur yuga”), and which the Vedas tell us comprise 4,320,000 years.40

Each Maha Yuga is further divided into four smaller yugas: Krita (sometimes Satya) Yuga, Treta Yuga, Dvapara Yuga, and Kali Yuga. However, these divisions are not equal in length, nor in character; in order, each represents 40-30-20-10 percent of a Maha Yuga. Below is a table for clarity.

|

Yuga |

Percentage of |

Length (years) |

|

Krita |

40% |

1,728,000 |

|

Treta |

30% |

1,296,000 |

|

Dvapara |

20% |

864,000 |

|

Kali |

10% |

432,000 |

|

Total |

100% |

4,320,000 |

As shown, each succeeding yuga is shorter than the preceding one, and the conditions in the universe, and in human society, progressively worsen as each yuga passes into the next. (Unfortunately, the details are far too complex to detail here, but an interesting point to ponder is whether human society degenerates because the universal conditions worsen, or whether it works the other way around).

For our purposes, the important point is that at the end of each Kali yuga, there is a sort-of “resetting” period, after which a new Maha Yuga begins, starting with a new Krita Yuga. One thousand Maha Yugas (4,320,000,000; 4.32 billion years), represents one day in an even longer cycle!41

Interestingly, we are said to currently be in a Kali Yuga (surprise, surprise), which began 5,124 years ago (does that number seem somehow familiar?) in 3102 BCE.42

Finally, the Cosmological Function is frequently where the explanation for the creation and purpose of human beings is to be found. In the Sumerian account of Atrahasis, humankind is created purposely to function “… as short-lived drudges to do the work … on earth.”43

In the Popol Vuh, the creation of humankind only occurs after three previous failed attempts, and their purpose is “… as essential mediators between this world and that of their patron deities and ancestors.”44

In the Tanakh, humans are created (male first and female later) as the pinnacle of God’s material creation, to serve as keepers of the Garden of Eden, and only later become mortal and subject to hard labor through their own failings.

The Vedas reveal that humans were simply a part of the original material manifestation of the universe, but the ease and quality of their physical existence alters with the changing quality of morality through the successive yugas.45